Sparring-partner

Par Thomas Gayet

CHAPITRE VIII – L’âme russe

Chapitre I – Roland

Chapitre II – On achève bien les buffles

Chapitre III – Tragédie racinienne

Chapitre IV – Claudio se prend pour Chang face à Lendl

Chapitre V – Les Petits As

Chapitre VI – Midinette

Chapitre VII – Claudio monte un peu court et se fait passer

Au centre des tribunes – aussi vides que mon palmarès – Lopez et Cerny s’apprêtaient à rentrer sur le court, ralentis seulement par les questions anglo-stupides d’un journaliste à tête de mouton. A l’autre bout du stade, la main lasse, je refermai sur moi la porte des toilettes. Dehors, des bruits d’eau, dedans, le calme un peu gêné et les odeurs. Trouver Marion. Eviter le directeur. Donc éviter Michel, dont j’avais pourtant besoin pour retrouver Marion. Pantalon baissé, ceinture rebondissant sur le carrelage. Casse-tête. Mal à la tête. On se calme et on boit frais. « Correction ». Ça ne voulait rien dire.

J’en étais là de mes pensées, inhibé par les bruits grouillants des usagers à gauche à droite – décidément, ça ne voulait pas. Des chasses d’eau vrombirent, rumeurs chassées par le souffle chaud des essuie-mains ultramodernes. Puis, quand enfin j’allais lâcher, une porte battante battit. J’accrochai en cours de route et malgré moi à une conversation téléphonique agitée, dans une langue inconnue qui ressemblait à du flamand. Je me contins comme je pus. Mû par une intuition divine, je décidai d’enregistrer les bruits de couloir avec mon téléphone. Je farfouillai en silence dans ma poche. A quoi cela pourrait-il servir ? Consonnesland. Je n’entendais qu’un bout de la conversation. L’homme parlait vraisemblablement d’un problème et de Iejov.

– Ikzinde prblemn. Ikztinde problmn enikwl niet ommetehlpe. Alsikval, terwijldevalvanhet ATP toernooi, ikval, valjewevallen.

A mi-consonne, une erreur de manipulation me contraignit à stopper l’enregistrement pour en relancer un nouveau.

– Hetmeisjevroegmegrappigvragen. Ikriskerengevangenismetditverhaal. Bijvoorbeeld. Ze zwarebegrijpikniethoededingenopditpuntkonkrijgen. Ergernog, ikwildealleenmaarhelpen.

– Jehebtjewerkgedaan. Eneenbeetjemeer. Maarjehebtjewerkgedaan. Uhoeftgeenzorgente maken. Hetisu die is. Hetmeisjeisgeenonoverkomelijkprobleem. Dingenzijnnietzo hard vallen.

– Weverwijderenmemijnrijbewijs.

– Zie …

Pas très claire, cette histoire. En sport-études, pas question de flamand première langue. Batterie faible, batterie très faible : plus de batterie. Il s’arrêta de toute façon peu après, car le journaliste à tête de mouton – je reconnus sa voix – lui aussi faisait caca comme tout le monde. A peine entré chez les hommes, il se mit à s’exclamer s’exclamer d’une voix sponsorisée par Doliprane Doliprane.

– Basil ! My friend, Basil ! How do you do ? How do you do ? It’s a real, real great, great, match over there on the court ! On the court ! C’est incroyable, ce tournoi, incroyable ! Que d’émotions ! Vraiment ! A tout, à tout à l’heure au club ! Au club !

Et de se diriger vers la cabine jouxtant la mienne. J’entendis en Dolby Surround les efforts polyglottes du journaliste ainsi que des pas lourds au départ de l’inconnu. En hâte, je terminai mes petites affaires et me ruai vers la sortie, espérant secrètement apercevoir au loin la silhouette du Basil en question. Mais Basil avait été avalé par les badauds. Bon titre de série B. Je fis machine arrière. Dans les borborygmes de la tuyauterie, je retrouvai le citoyen du monde éclaboussé d’ablutions. Je lui tendis une main qu’il me rendit mouillée.

– Excusez-moi, cher ami. Auguste Loisel, sparring-partner !

– C’est vous notre coqueluche ? C’est vous ! Ah, ah ! Cher ami, quelle aubaine. Quelle aubaine. Alors, on investigue ? On renifle, on flaire la piste ?

– Dites-moi, je n’ai pu m’empêcher de surprendre votre conversation… Votre niveau d’anglais est très impressionnant, d’ailleurs, encore plus qu’à la télévision. Stanford ?

– Cambridge. Mais je perds, je perds ! C’est l’âge, que voulez-vous… Un homme devrait apprendre toute sa vie, ne pas se contenter de vivoter sur ses acquis. Qu’en pensez-vous ?

– C’est mon idée.

– Le tennis, vous le travaillez tous les jours, pour ne pas perdre, je suppose ?

– Et plus encore, évidemment.

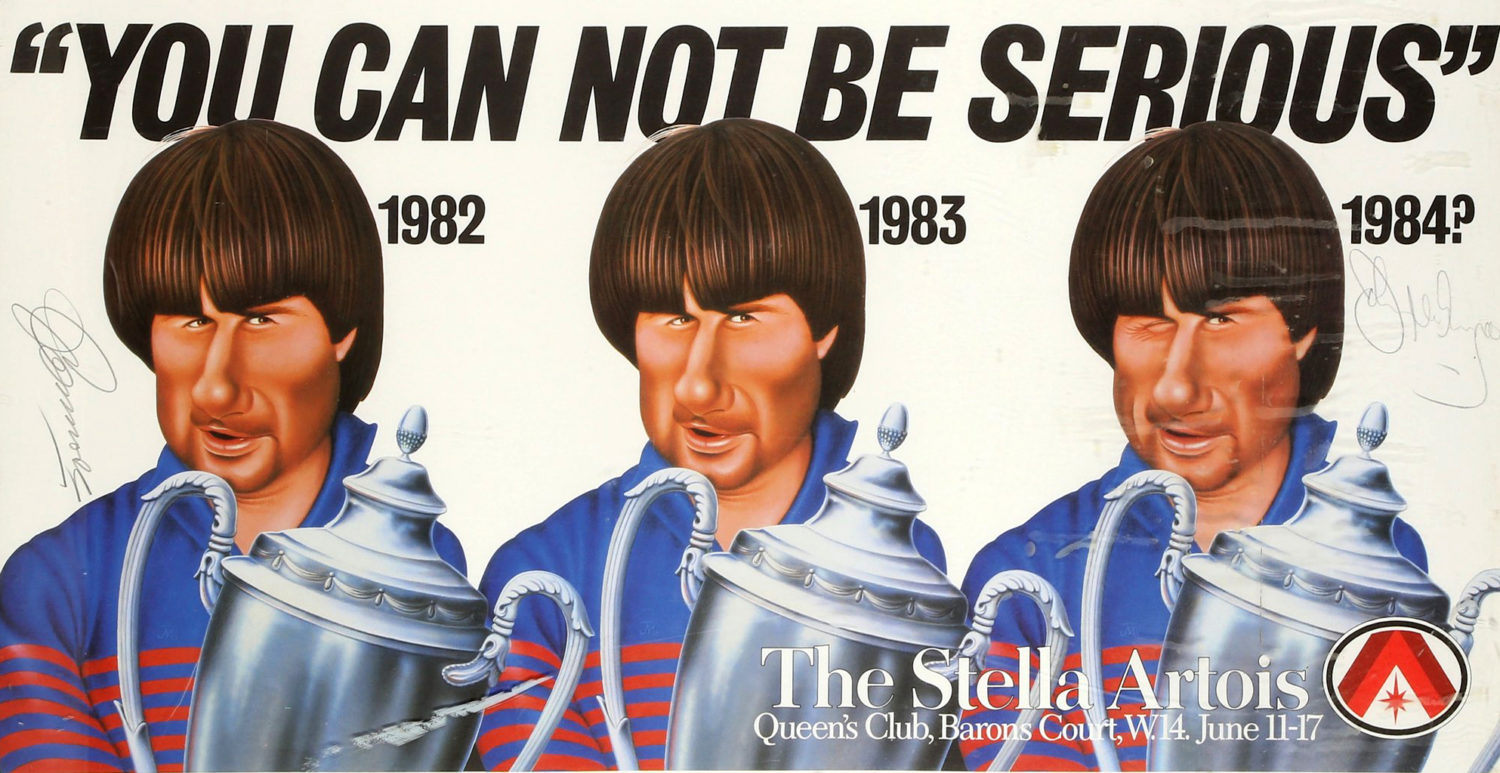

– Quand on a gagné les Petits As, forcément.

– Je n’ai… Pour revenir à votre conversation. Qui était ce Basil que vous saluiez si chaleureusement ?

– Basil ? C’est the chairman* (en anglais dans le texte), le seul, l’unique. Un arbitre de classe mondiale. Et une douceur, avec ça. Une modestie. Un honnête homme ; il faut dire : formé en France ; cocorico ! Je le dis car la Belgique – c’est bien logique – le revendique comme l’un des siens. Une histoire de naissance ; de naissance, vous m’entendez ? Le pays du cœur contre le pays de fait : seul un e final et muet fait défaut à son nom pour qu’il ne soit, lui aussi, éligible à la légion d’honneur, comme nous. Je parle en toute confiance, sur ce terrain-là, et entre nous I have been approached ! Approached !

– Son nom de famille ?

– Van der Berckerst. Berckerst. Ersst. Ah ! Le flamand. Quelle langue !

En dessinant un cercle avec ses deux doigts pour mieux matérialiser la précision du dire, il faisait siffler ses sonnantes comme des serpents sur nos cerf-têtes.

– Oui, vraiment, seul le e lui manque. Il arbitre, en ce moment ?

– Il officiera demain.

– Merci, beaucoup Amiral. Seul le titre vous manque.

– C’est mon faible.

Je sortis des toilettes. Une piste ! Une piste, enfin ! Contaminé par cette manie de toujours s’y redire à deux fois, je fendis la foule en direction du court central. Je tournai et retournai les informations dans ma tête et cherchai le point d’ancrage avec cet indice : « Correction ».

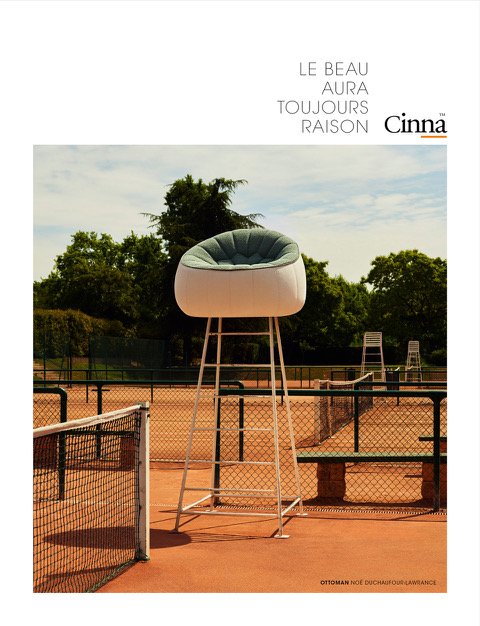

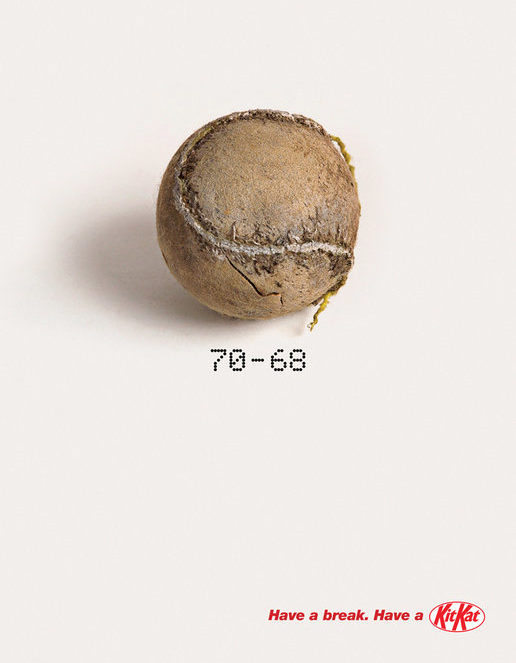

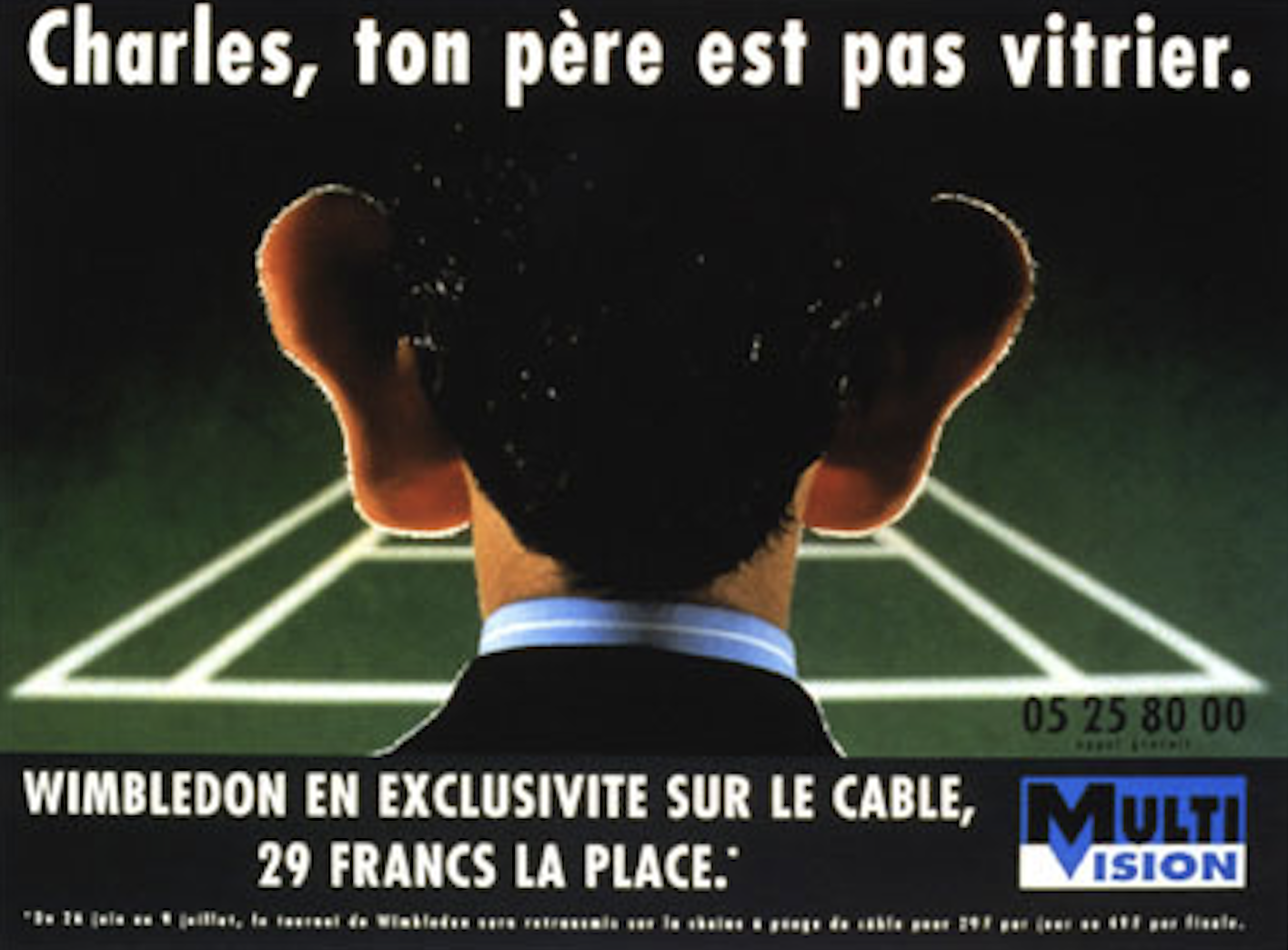

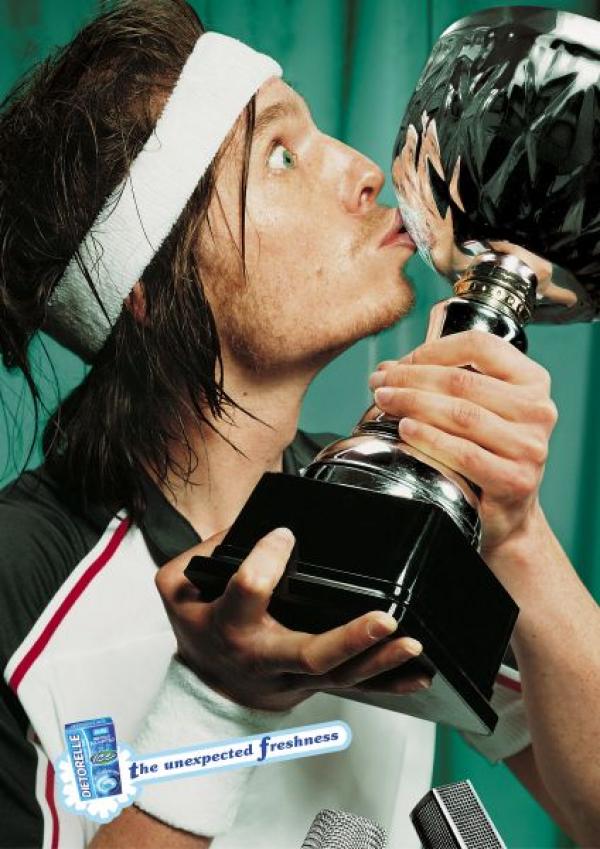

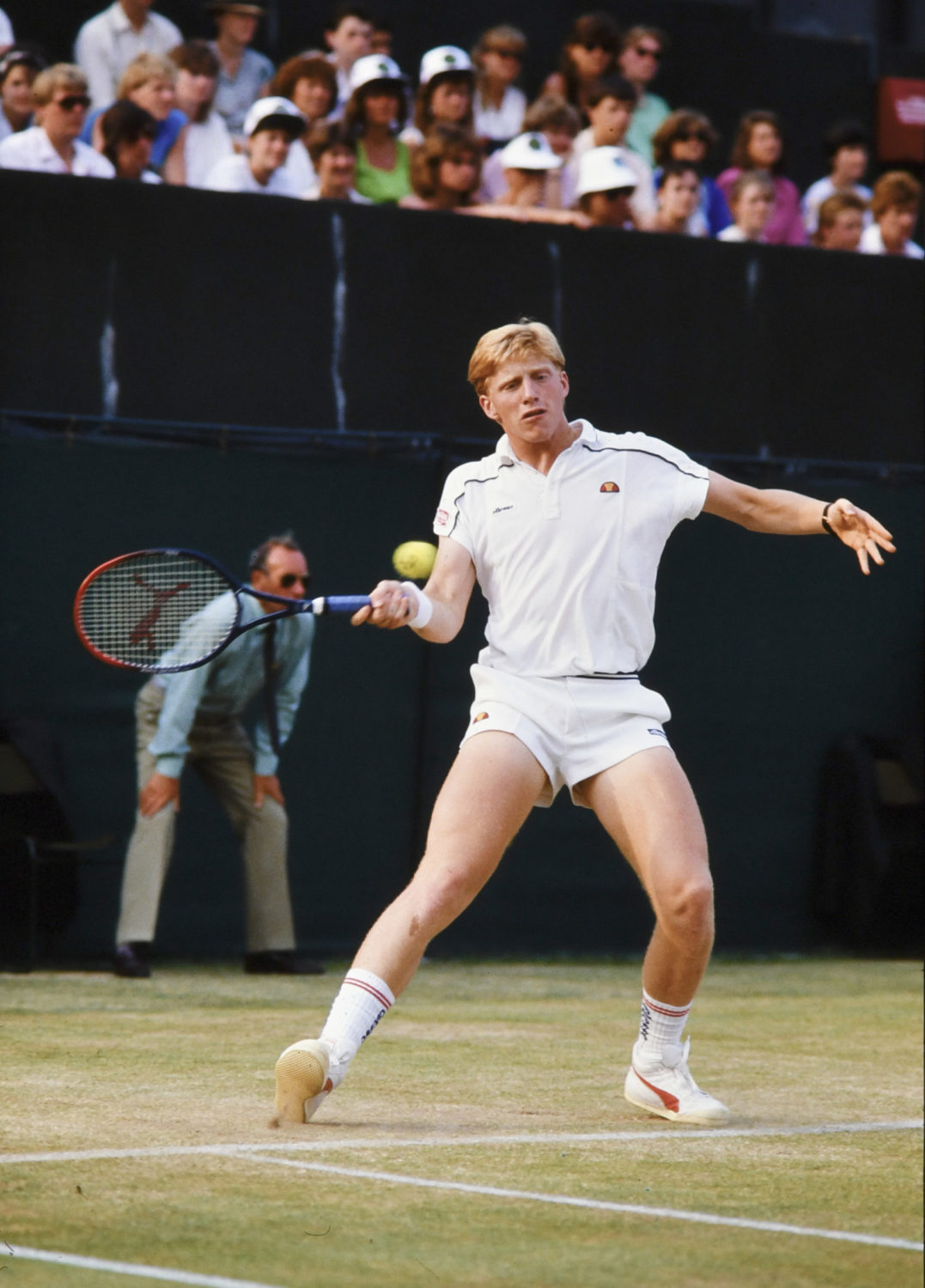

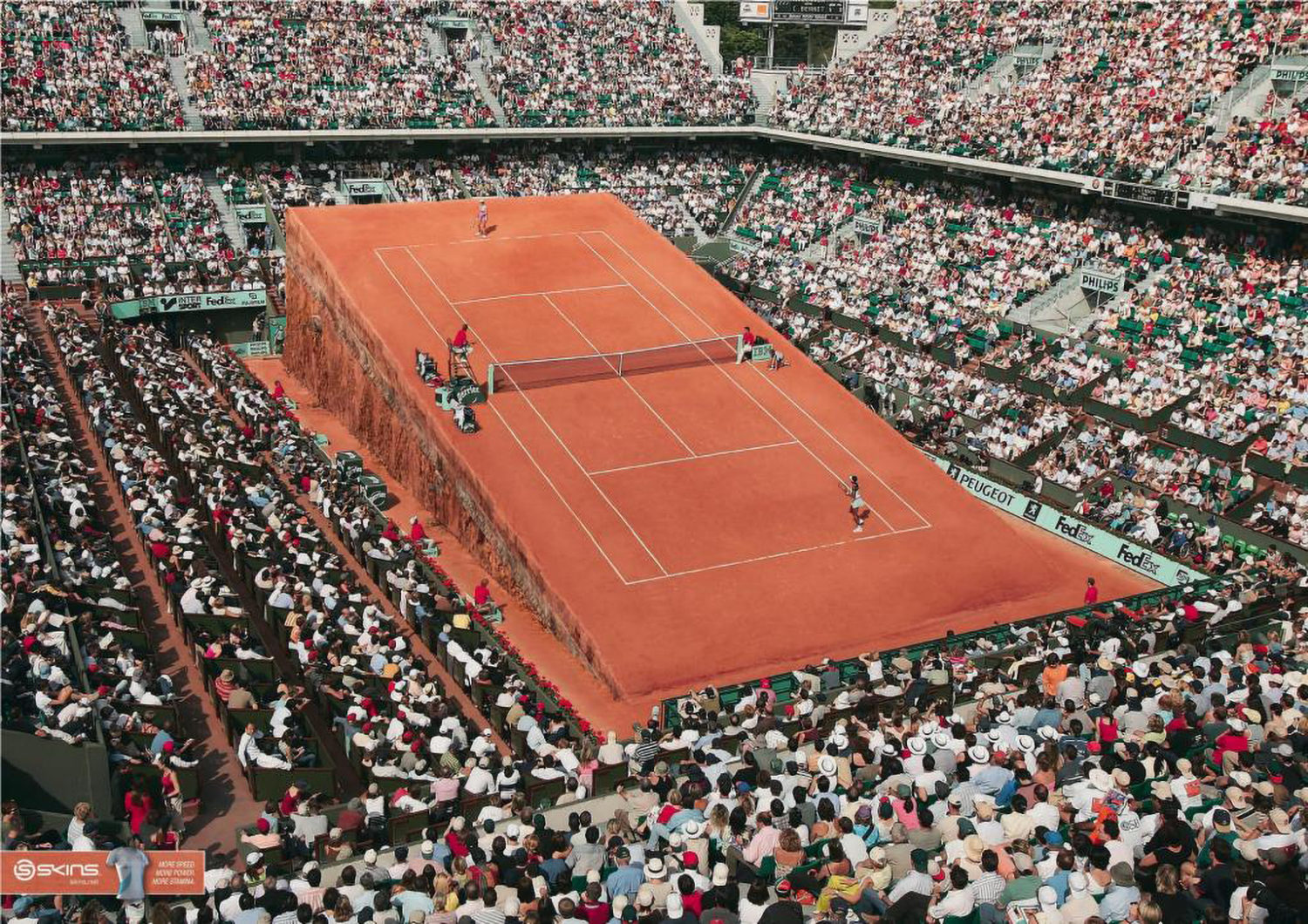

« Correction ». Sur le court, il en était question. Cerny jouait le match de sa vie contre un Lopez impuissant. Placé en hauteur, juste sous la cabine des commentateurs, je devinais malgré la teinte de la vitre l’ennui qui les gagnait. Je crois que Cerny m’aperçut au changement de côté quand, du menton, il esquissa un signe amical. « Il m’a vu, les filles ! Les mecs : il m’a vu ! Moi ! » Midinette. J’étais sous le charme. Service Cerny à plus de deux-cent : « AHOUUUUTE », hurla le juge de ligne qui voulait sûrement dire faute mais avait été rattrapé par la peur de mourir. « Correction, the ball is good. Replay the point », statua l’arbitre de chaise.

« Correction ».

Basil Van der Berckerst chez les arbitres. Basil Van der Berckerst qui craignait un problème.

Marion chez les arbitres. Marion qui adorait les problèmes.

Un plus un égalent vite. Je quittai le court aussitôt, laissant Cerny voler de ses propres ailes vers une victoire inévitable.

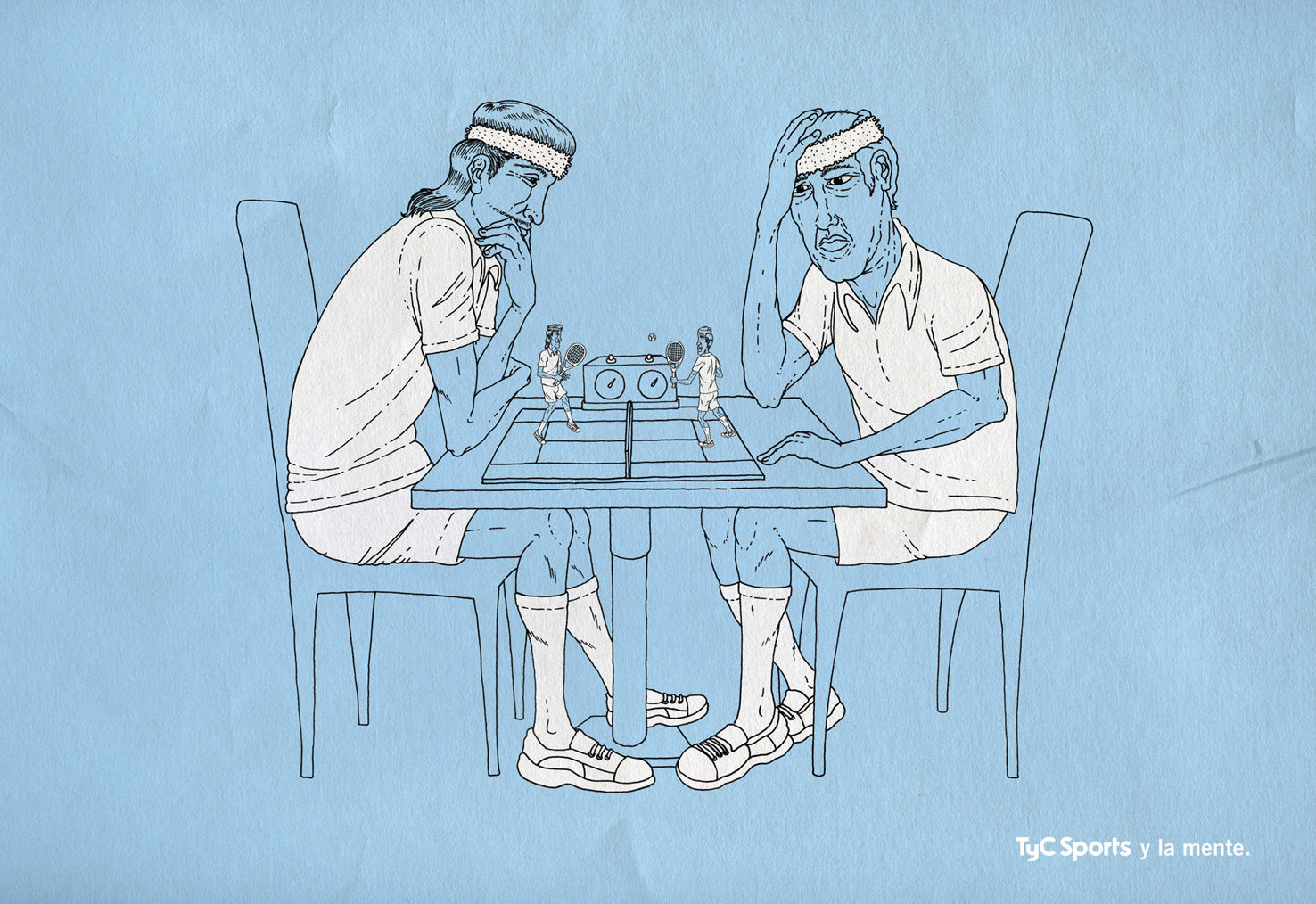

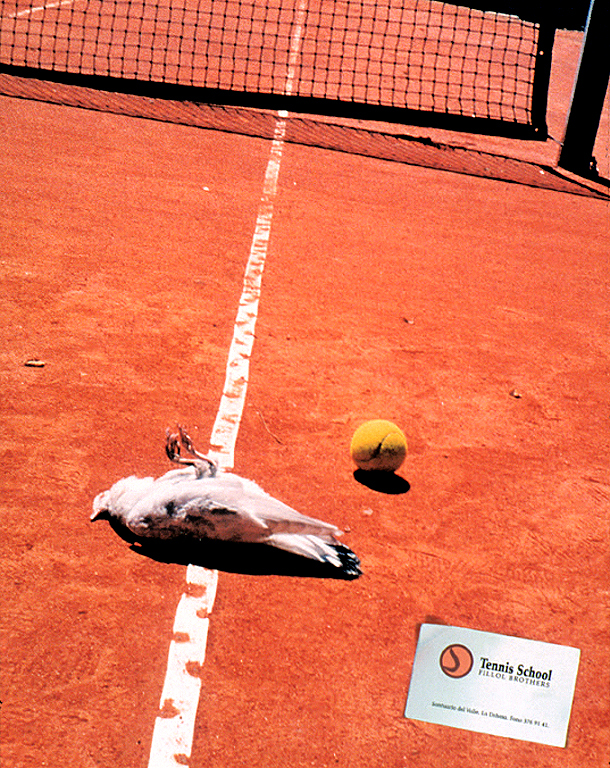

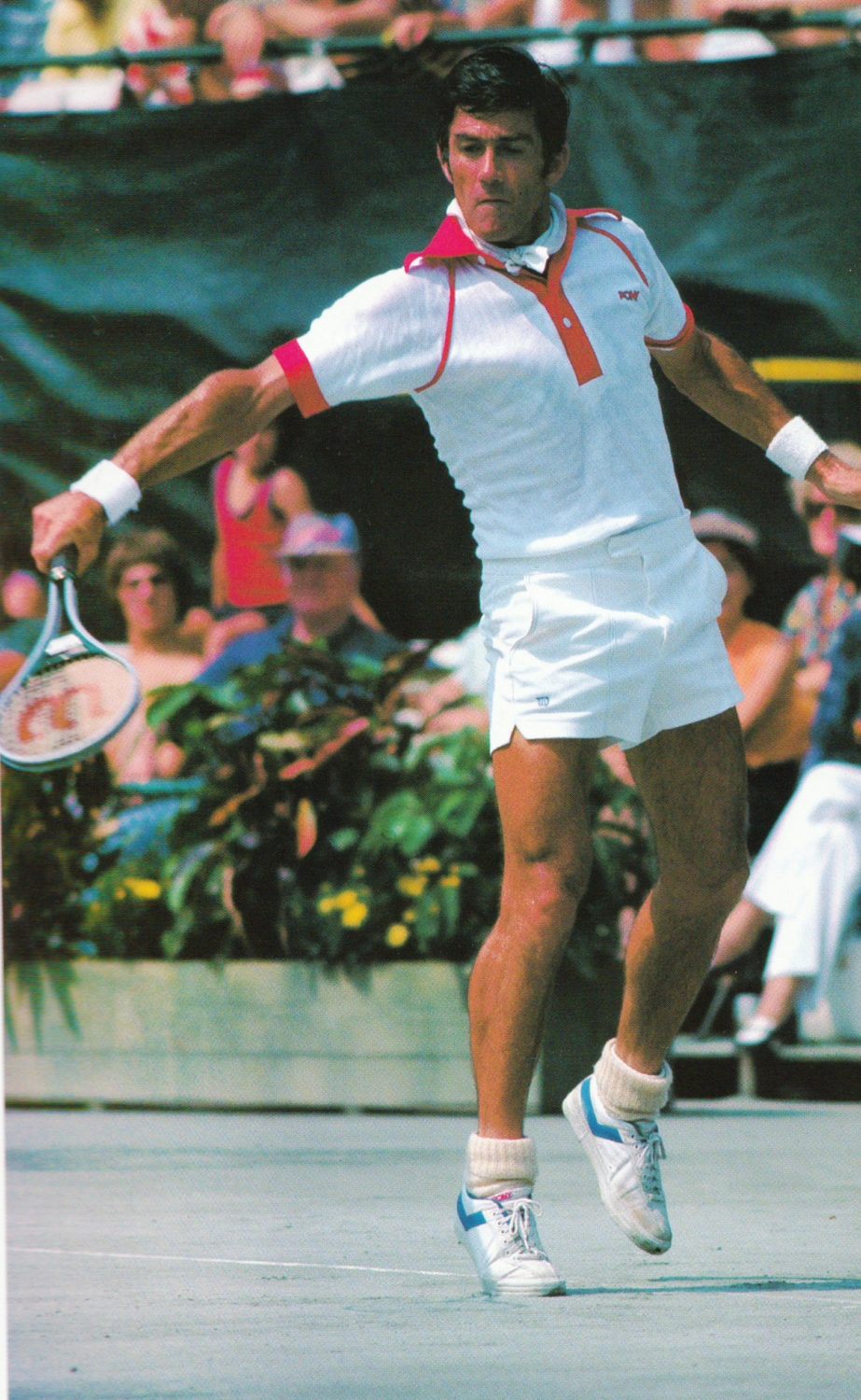

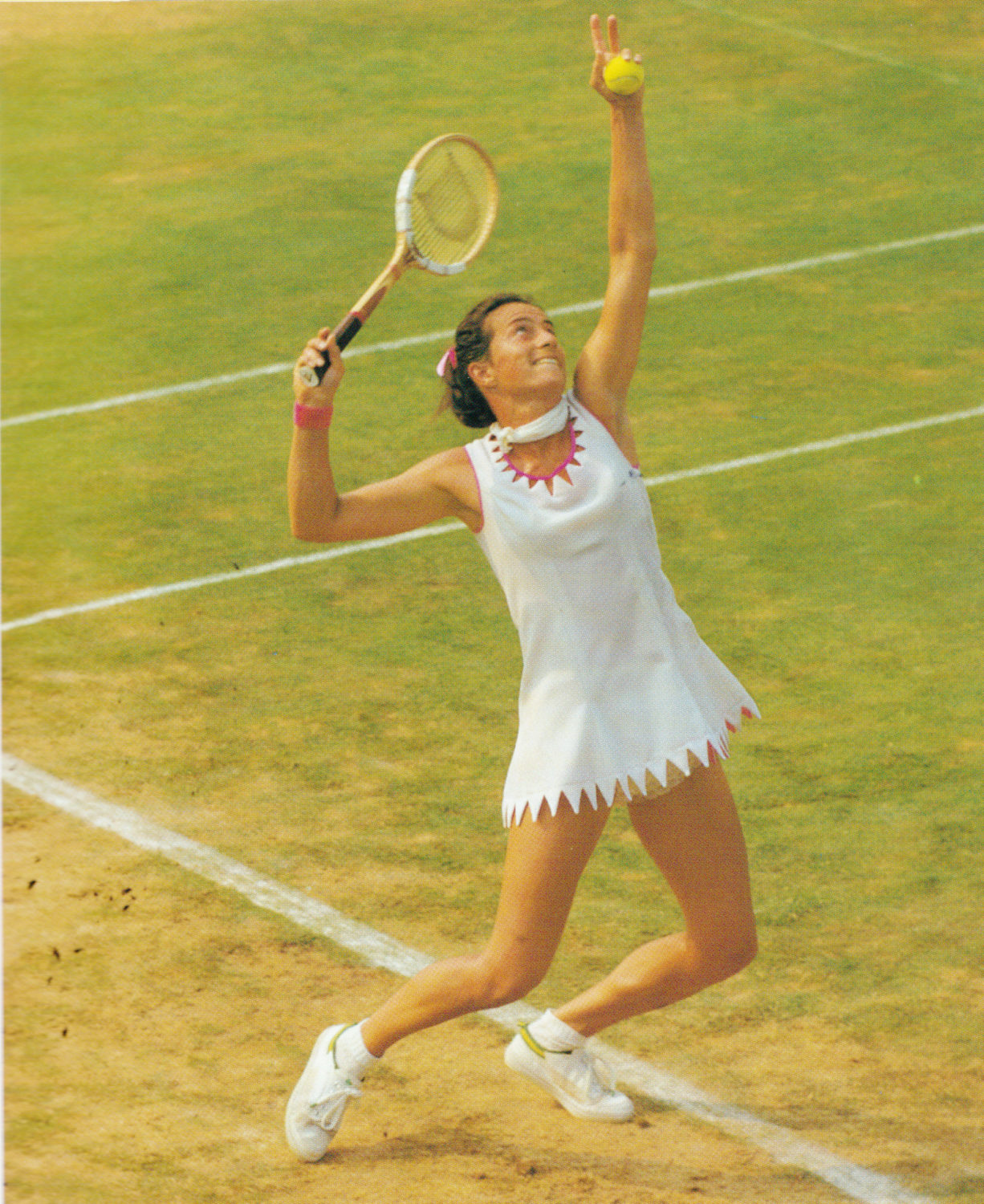

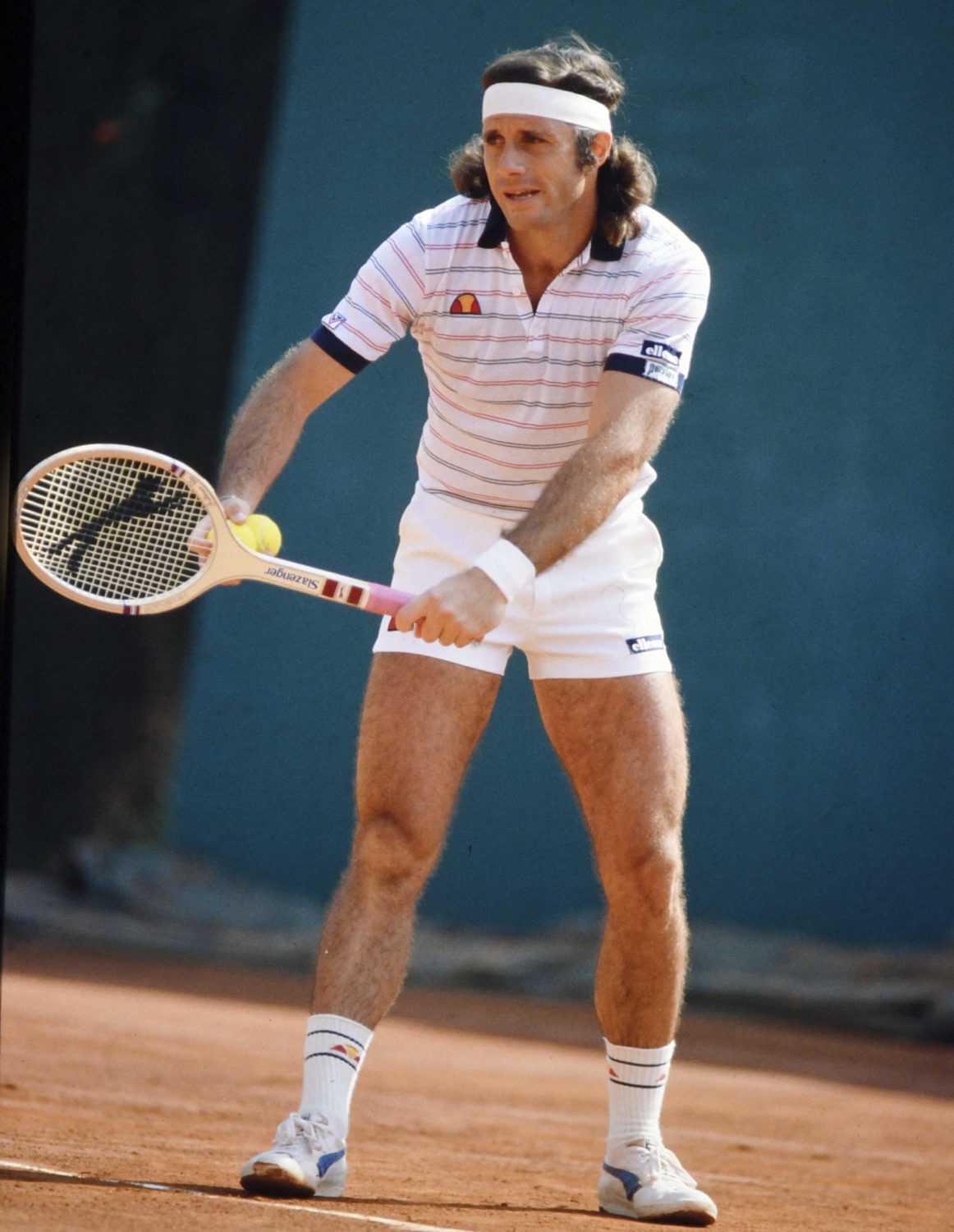

Il existe deux types d’arbitres : les arbitres en polo rouge et les arbitres en chemise bleue. Deux classes sociales bien définies, écho Lacoste aux mondes qui séparent les coutumiers de la tribune présidentielle des visiteurs à bob Perrier. Tenus de croiser leurs homologues en rouge, les arbitres en bleu, pantalon crème et veste marine, poche revolver barrée d’un crocodile à échelle un, s’adressent à eux comme des patrons de groupes publics, quittant le confort spacieux d’un bureau avec vue sur Paris pour assurer une journée durant l’inspection bimensuelle des machines-outils dans leur usine de Louvain, s’intéressent à leurs ouvriers : comme à des choses transitoires, pratiques et malléables – en attendant l’essor de la technologie. Les uns trônent sur une chaise et disposent d’un micro avec lequel ils haranguent la foule. Les autres hurlent des onomatopées au hasard en agitant les mains. Autant de différences qu’entre un pilote de ligne et un aiguilleur du ciel.

Il me fallait choisir mon camp. Aborder les capés, c’était m’exposer à un dédain vaporeux ; entreprendre les sans-grades revenait à interroger la cinquième roue du carrosse. Avant de pénétrer dans le salon cosy, fauteuils cuir anglais et sourires entendus, j’essayai un instant de me mettre à la place de Marion. C’était elle, que je cherchais : nul doute que sa piste recoupait la mienne, d’une manière ou d’une autre. Comment s’y serait-elle prise ? Je poussai la porte vitrée.

– Bonjour, je souhaiterais obtenir des renseignements en vue d’un documentaire consacré à l’arbitrage, ce grand corps oublié sans lequel le tennis ne serait pas ce qu’il est. J’aimerais savoir comment approcher les plus grands arbitres mondiaux, pouvoir leur laisser la parole, qu’ils racontent leur expérience, leur pression, ce que représente aussi d’arbitrer sur un grand match. Basil Van der Berckerst, par exemple, je pense à lui spontanément.

– Ah, mais j’ai déjà vu votre collègue à ce sujet, hier. Je l’ai réorientée sur la Fédération. C’est encore le plus simple. Moi je ne suis qu’agent d’accueil, vous comprenez.

– Mon collègue ? Ma collègue, bien sûr ! Grande, brune, les yeux bleus et trop grands, l’air de n’avoir jamais commis la moindre crasse sur terre ?

– C’est elle.

– Et donc, vous l’avez renvoyée vers la FFT. Hmm… Je comprends. Que lui avez-vous dit d’autre ?

– Elle m’a demandé si elle pouvait visiter le pavillon, histoire d’avoir des repères pour un éventuel tournage. Je l’ai laissée farfouiller. Vous savez, on s’ennuie, ici. C’est pas tous les jours qu’ils viennent nous voir, les gens de la télé. Et puis elle est gentille votre collègue, ça se sent tout de suite, ça, la gentillesse.

– Donc les repères ont été pris. Bien. Très, très bien. Bien, bien, bien.

De la répartie, Auguste, de la répartie !

– Eh bien, tant mieux, très bien tout ça. Pas la peine, donc, que je me balade à mon tour, hein, puisque tout a été fait ? Non ? Hein ? Bien. Très… Hum. Très bien. Je vous remercie. Bonne journée. Alors, donc.

– En vour !

– En vour ?

– En vous remerciant. C’est plus convivial, comme ça, non ?

– Aur, dans ce cas.

Chou blanc, du genre de chou qui sert à faire des soupes quand il fait trente degrés. L’aigreur est humaine. En sortant du pavillon, mon attention fut capturée par un chuchotement directement issu d’un coin ombragé, sous un chêne bourgeonnant.

– Pssss…

– Pssss ?

– Vous êtes Auguste Loisel ?

La voix de Dark Vador imitée à la bouche.

– C’est votre vraie voix ?

– Vous cherchez des informations sur Basil Van der Berckerst ?

Je contemplai un instant la silhouette. Elle était familière, sous les lunettes aviator, la casquette et le polo rouge.

– Vous êtes un juge de ligne ? Un ou une, d’ailleurs, on ne sait plus très bien.

– Retenez bien ceci. Basil Van der Berckerst a arbitré deux matchs très importants au cours de l’année écoulée. L’un a fait basculer la hiérarchie mondiale. L’autre a vu la vie d’un homme basculer.

– Père Fouras ? C’est vous ? Ecoute Marion, ça commence à bien faire ces histoires.

Elle m’attira vers elle tout en continuant à chuchoter.

– J’ai retrouvé la serviette.

– Quelle serviette ?

– Celle qui a servi à traîner le corps de Belluci. La serviette. Celle que le ramasseur de balles a posée sur sa tête. La serviette pleine de sang, tu sais. Elle n’était pas pleine de sang après ; elle l’était déjà avant ! Un mort, ça ne saigne pas ! D’ailleurs, le ramasseur de balles a disparu. Rayé des registres. Une aubaine, cette photo. C’est notre seule piste. Donc, je reprends : on traîne Belluci sur la serviette avant l’interruption, via le carré des télévisions, en passant par le sous-sol. Là, quelqu’un d’autre prend le relai. On profite d’un moment général d’inattention – le feu d’artifice – pour glisser Belluci sous la bâche. Puis on repart comme si de rien n’était. Pourquoi ? Comment ? Parce qu’on pouvait être là, on devait, même, se trouver à cet endroit précis : rien d’anormal. Plus tard, on trouve le cadavre : la serviette qui a été utilisée pour traîner Belluci doit disparaître. Tu me suis ? Un ramasseur de balles la jette sur le corps et personne ne comprend rien. Moi, je commence à y voir clair, maintenant. Tout est clair, oui. Il me manque le mobile. J’ai mon idée. Mais je n’ai pas les preuves. Tu as trouvé l’arme ?

L’arme ? Je sais à quoi m’en tenir, mais je prends mon temps. Et Racine ? Il est au courant ? Non, bien sûr. Et toi, qu’est-ce que tu fais, déguisée en juge de ligne ?

– Je travaille, patate. Je travaille. Je rôde. Et j’arbitre, aussi, ce qui est très amusant. Les règles du tennis, c’est vraiment de la petite bière. Pour l’arme, dis : ils n’ont rien analysé dans les débris du Tenniseum ?

– Je vois qu’on a la même idée.

– Dis-le à Racine : il faut analyser, absolument. La preuve est là. – —- Johnson ? Ils ont arrêté Iejov ?

– Je te revois, un jour ?

– Ils ont arrêté Iejov ?

– Iejov devrait être relâché dans la journée. Je te revois un jour ?

– Relâché, mais pas tiré d’affaire. Le dopage.

– Je te revois un jour ?

– Ça a déjà fuité. C’est évident. C’est dangereux. Essaie de confronter Van der Berckerst. Il passera ici avant son match. Tu seras peut-être plus chanceux que moi.

– En attendant Berckerst, je te revois ? Un jour ?

– Peut-être.

Elle m’embrassa sur la joue et partit en soignant ses entrechats. Pour l’arme, je ne comptais rien dire à Racine. Une intuition. Un pressentiment.

Je me positionnai en faction. Tel un sioux sifflotant de guet sur la montagne, j’attendais l’arrivée de Basil Van der Berckerst.

J’en étais quitte pour la Belgique. Deux minutes plus tard, je tombais sur Michel Le Bas, dont le moral suivait implicitement la courbe de son nom.

– Bon dieu, tu es là ! Alors Iejov ?

– C’est-à-dire que…

– Je sais bien que ! Je sais. Je sais très bien que ! Partout, tu m’entends ? Le directeur te cherche partout ! L’inspecteur. Décrocher ! Il refuse ! Partout, qu’il te cherche.

– Michel, remets de l’ordre dans tes idées et dans tes phrases, je ne comprends rien.

– Imagine, un peu : un mort sur le Chatrier. Un mort dans un hôtel de renom. Des éliminations en pagaille. Le numéro trois mondial arrêté ! C’est inhumain de me faire ça, à moi, un vieux, je suis vieux, je vais crever. Je ne peux pas canaliser seul les angoisses du directeur, il faut m’aider mon vieux.

– Je croyais que c’était toi le vieux.

Yeux mouillés et slip itou.

– De l’esprit ? Tu fais de l’esprit ? A ce moment-là ? En ce moment, là, maintenant, ici ! Alors que le directeur me croit responsable de la mort de Johnson ? « Le Bas, qu’il me dit, Le Bas, les sparrings, c’est votre affaire et vous n’avez rien trouvé de mieux que de colloquer Johnson dans la chambre à côté de celle de Iejov ! » Il ne veut pas comprendre que ce n’est pas moi, que je ne connais pas Johnson et que Johnson ne travaillait pas sur le tournoi. Il ne veut pas. Il refuse. C’est Le Bas, le problème. Et le président de la fédération ! Furax, le président.

– Ne te tracasse pas, tu sais, Iejov n’a pas tué Johnson. Claudio témoigne.

– Alors celui-ci, il se range du côté de Johnson ? Mais c’est une association de malfaiteurs ! Rien n’est clair dans cette histoire, sauf le scandale ; tu imagines le scandale ? Le directeur de l’hôtel a appelé le directeur des affaires culturelles russes qui a appelé le directeur du tournoi. De directeur à directeur, je te laisse combler les vides ; la politesse, mais les relations, le protocole, mais les menaces, tu te figures bien. Le danger. Les ambassadeurs. Les ministres. Le protocole de Kyoto. Kyoto ? Ici ! A Roland !

– Emmène-moi voir le directeur si ça peut te rassurer.

Il agrippa mon bras et le serra entre ses doigts roides. Il avait peur que je ne m’enfuie. Je me sentais comme un visiteur d’hôpital auprès d’un parent condamné. Cependant, le tableau d’affichage consacrait la victoire en trois sets d’Ambrosz Cerny. Il existe des bonnes journées. Mon sourire déplut à Michel.

Dans le bureau du directeur, deux moustachus rougeauds de soixante ans, portant documentation des années soixante-dix et forçant leur regard pour lui donner de l’allant, refusaient de s’avouer vaincus.

– Puisque je vous dis que cela ne nous intéresse pas ! Nous ne sommes pas un club omnisports, nous ne faisons que du tennis, ici ! Vous voyez bien que je suis occupé !

– En s’affiliant à la Fédération française des clubs omnisports, Roland Garros entrerait de plain-pied dans le XXIe siècle ! Il disait ça avec son teint de photo jaunie.

– Pour vos bénévoles, ce serait un vrai plus, une vraie garantie sociale et sociétale ; sans compter sur votre crédibilité auprès des acteurs publics pour obtenir des subventions. Et puis, j’oubliais le plus important : l’assurance responsabilité civile des mandataires sociaux ! En cas d’accident, par exemple : regardez ce qui est arrivé à Belluga.

– Belluci.

– Oui. Regardez ce qui lui est arrivé.

– Mais… Mais il n’a pas eu d’accident, il a été assassiné ! Et puis je n’ai absolument pas besoin de subventions puisque je dépends de la Fédé de tennis, mais vous êtes fous, mais partez, enfin !

– Vous avez gagné : je vous laisse notre carte et de la documentation. Et ma ligne directe, c’est celle-là, là, celle qui est surlignée. Non, oui, voilà, attendez, je vous mets un coup de Stabylo dessus, là, voilà !

Mais je m’en fous de votre carte et de votre documentation ! Mais vous êtes qui ? Qui vous a laissé entrer ?

Le directeur était en proie à une agitation six à sept fois supérieure encore à celle de Michel, digne d’une publicité radiophonique pour des soldes à l’hypermarché. Quand les deux hommes partirent, il se reprit un peu. Sur son bureau, une lettre anonyme rédigée en ces termes :

« On étouffe un contrôle et on ne contrôle plus rien. Mieux vaudrait que Iejov ne réapparaisse pas. »

– Rien du tout. Rien étouffé du tout, moi, rien. Du tout. Qu’est-ce que c’est que cette histoire ? Iejov est condamné ? On lui a coupé la tête, on va la lui couper ? Qu’est-ce que j’annonce, moi ?

Il ne me parlait ni à moi, ni à Michel, ni à lui-même. Je crois bien qu’il s’adressait à Dieu – peut-être qu’il se le figurait à l’image de Jean Borotra, dans son panthéon personnel.

– N’annoncez rien. A priori, Iejov est innocent, du moins du meurtre de Johnson. Si la police ne veut pas vous répondre, c’est qu’elle n’a rien à vous communiquer. En attendant, pour cette histoire de lettre…

– Vous avez vu ?

– J’ai vu. Pour cette histoire de lettre, un conseil. Laissez faire les choses. Si Iejov devait être accusé publiquement, vous seriez l’une des personnes les plus protégées du scandale, de par votre statut. Et puis, ne vous faites pas d’illusions : que vous agissiez ou non, l’affaire sortira. Tout le monde est au courant. Allez, ne vous faites pas de bile. C’est la vie, ça va passer.

De sparring-partner, voilà que je virai psychiatre goguenard. Le téléphone sonna. Au même moment, la porte claqua bruyamment.

– Disease the scandal. Disease not proper. Disease not the way Russian citizens are meant to be treated by French tournament. I protest. I have staid in prison the whole night. I am willing to step out of the tournament. I want excuses. I want excuses now.

– Mais bien évidemment, nos excuses éternelles, M. Iejov, c’est effroyable, effroyable ce qu’il se passe, ce qu’il vous arrive. Et la perte de cet être cher, qui plus est, effroyable, ils vous ont relâché ?

Iejov, avec sa barbe naissante et déjà drue, ses traits tirés, ressemblait à un Raspoutine de roman. La porte claqua à nouveau car l’entraîneur fit irruption. Du bout des doigts, il cherchait à ramener vers lui la lettre incriminante, la faisant glisser par à-coups.

– I now am willing to train. Now. I want a court and I want a partner to execute with me.

Le terme exécuter, dans sa forme peu idiomatique, me provoqua des picotis dans le nombril. Tous les regards se tournèrent vers moi. Le directeur enveloppa sa voix de pivoines enchanteresses.

– Right now, monsieur. Voici votre partenaire. Loisel, Michel, je vous laisse vous occuper de Monsieur Iejov, n’est-ce pas ?

Le principe même du malheur est que vous ne pouvez jamais lui échapper : vous pouvez courir, fuir, vous cacher sous un drap ou acheter des gris-gris, il se trouvera toujours une noix de coco pour vous tomber sur la tête, quand ce n’est pas une balle perdue ou un terrible secret de famille. Nous nous mîmes en route. Ce que j’étais fatigué ! Toujours au service des autres ! Auguste, passe-moi le sel ; Auguste, je peux copier sur toi ? Auguste, tu pourrais aller chercher ma mère à l’aéroport, à Beauvais ? Et moi ? Moi, je fonçai au vestiaire chercher du matériel, sous l’œil moitié-fermé, moitié-cramoisi, entièrement haineux de Sergueï Iejov.

Dans le vestiaire, j’avisais mon casier. Pour une raison obscure, la clé tournait à vide dans le petit caisson. Impossible d’ouvrir. Normal : c’était ouvert. Affaires sens-dessus-dessous. On ne m’avait pas volé mon short. Que pouvait-on chercher ? J’enfilai mon t-shirt à l’envers, mes chaussures au hasard, enlaçai mes lacets. Puis je me mis en train, hauts les jambes, plus haut encore, genoux sur le menton en une course ridicule. A chaque mouvement ma cuisse gauche me lançait, comme râpée, épilée même, par un objet tranchant. Je fouillai et trouvai une carte de visite. Au nom de Van der Berckerst, arbitre professionnel dépendant de l’ATP. Au milieu, un mot, griffonné au stylo rouge pour produire plus d’effet.

« Vous êtes raisonnable. Ne gâchez pas tout. D’autres pourraient en souffrir et vous, par contagion. »

Petit, je me souviens que mes parents avaient colloqué dans les toilettes un recueil d’énigmes et de rébus qui faisait la joie de mes heures sur le trône et le désespoir de mon frère, lequel trouvait systématiquement porte close et patientait en gémissant. Le niveau général du recueil était en dessous de tout : il vous rendait intelligent sans faire appel à vos neurones. Le mot glissé dans mon short de sport devait constituer le volume ultérieur, interdit aux enfants de moins de 160 de QI. Juste avant de sortir du vestiaire, je le fourrai à la va-vite dans ma poche. Iejov m’attendait. Il tapait du pied pour me le signaler. Sans un mot, nous partîmes pour un court extérieur. Je tripotai la carte, dans ma poche. A leur regard, je supposai que les badauds devaient y voir quelque chose de sexuel.

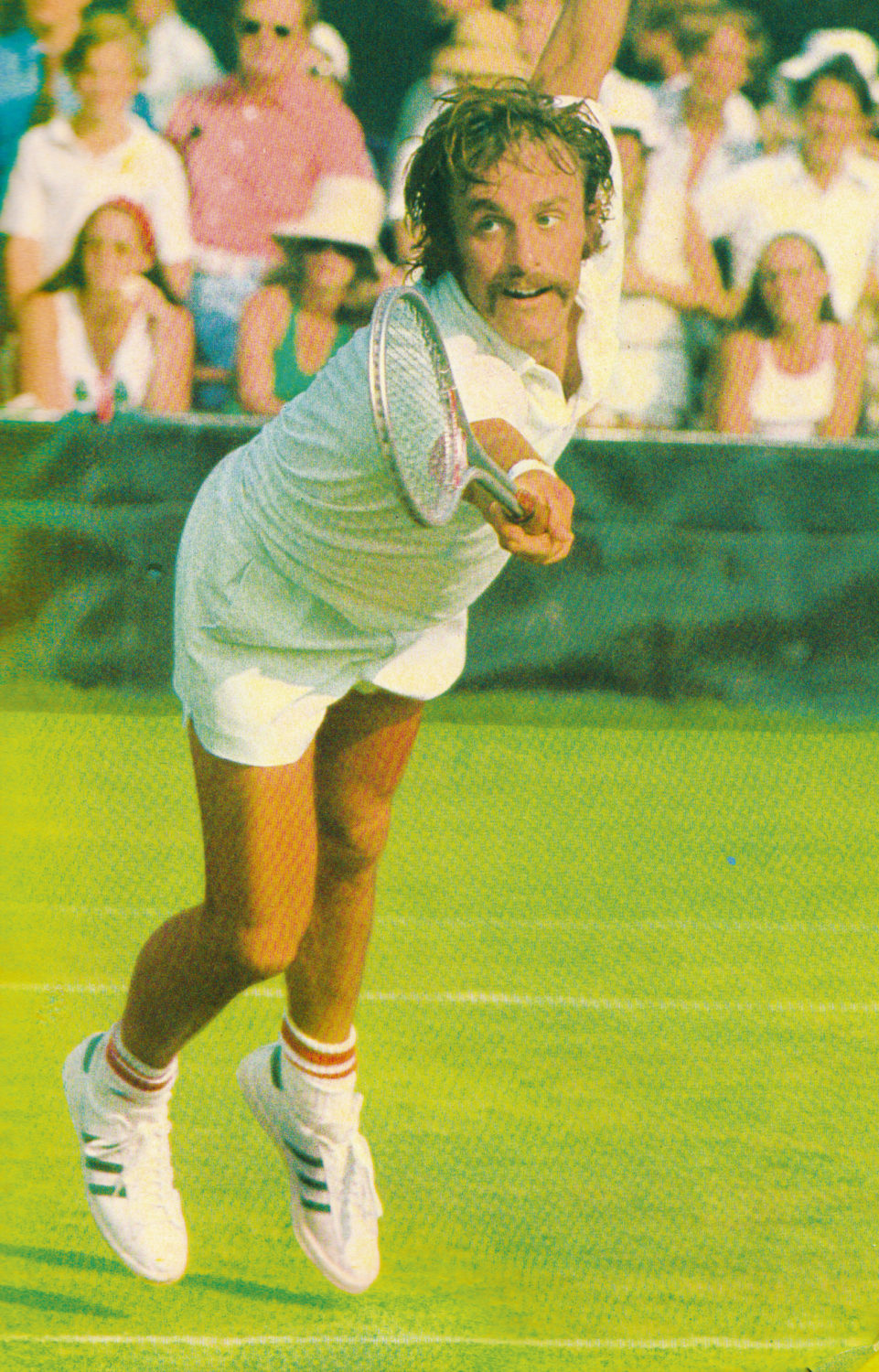

Pas chassés, pirouettes, effets de manche ; Racine au bord du court suivait la balle des yeux. Quand il l’aperçut, Iejov se mit à gronder en russe diverses insanités. Profitant de la protection tacite de la gigue policière, j’attendis une pause dans le rythme infernal imposé par le slave pour me pencher vers lui. L’air de ne pas y toucher, je lui dis, en anglais :

– Vous lui devez une fière chandelle à Claudio. C’est un ami, lui, vous savez ? Friend. Donnant-donnant, non ? On efface l’ardoise ?

Le regard qu’il me jeta introduisait la haine dans le chaos de son vide intérieur ; le big-bang à l’envers, un truc que les scientifiques mettraient quatre mille à décoder proprement.

– Je suis aussi ami avec Racine, l’inspecteur. Votre histoire d’ordinateur, là, ça pourrait générer des problèmes. Il y a des rumeurs, des lettres anonymes. Mais rien d’impossible à arranger. Je suis arrangeant, moi : la preuve : vous avez besoin d’un sparring, et hop ! Je me rends disponible. Je suis là. On impose, je dispose. Que vous a demandé Butler concernant Belluci et Stern ? Que savez-vous sur lui ? Comment saviez-vous qu’il allait perdre son match ?

Je livrai mon plus beau sourire pour accompagner ces paroles. C’est alors que je vécus les dernières secondes de Belluci dans leur version édulcorée, moins létales. Un gros coup de raquette envoyé en pleine gueule et un saignement corollaire qui jaillit de mon crâne. Je m’effondrai au sol, conscient, beaucoup trop conscient compte tenu de la douleur. J’en étais quitte pour les initiatives. Il faut savoir rester à sa place. En attendant les secours, je ne bougeai plus de la mienne, bien accroché au sol avec les yeux mi-clos.