Africa Loves Tennis,

EDGE Plays Matchmaker

Translated by Marc Woodward Services

“There are very few African tennis players on the tour. In recent years, we’ve seen Malek Jaziri, Ons Jabeur, and Selima Sfar, all three from Tunisia. And before that, Younes El Aynaoui, Hicham Arazi, and Karim Alami from Morocco. But that’s about it. Can you think of a black African player who has made strong inroads in the tennis world?”

By prompting you to rummage through your tennis memory, the author has deliberately turned his article into a guessing game. But fear not, the answer to this burning question is revealed at the very end by flipping the script (like you used to with Mickey Mouse Magazine back in the day). The question itself is posed by a die-hard tennis fan who cofounded EDGE, the international tennis agency dedicated to helping young talents spread their wings in order to reach the highest level.

The agency is familiar to COURTS readers, having been featured in several articles providing behind-the-scenes access to the ITF, WTA, and ATP circuits. But for the uninitiated, and to keep it concise (think listing French Open champions in the Open era), EDGE is a player development agency with a unique model based on the long-term partnerships it forges with its players.

EDGE’s philosophy is to provide support to young players, without discrimination based on nationality or even gender – the agency notably helps female talents, which is unusual in the tennis industry. “EDGE works with Russian and Belarusian players, while also being the official partner of the Ukrainian Tennis Federation and helping several families from that same country, explains Rick Macci, a world-renowned coach and the mastermind behind the project. We also work with a young Israeli U13 world #1 while representing the highest-ranked Arab player on the ATP Tour.”

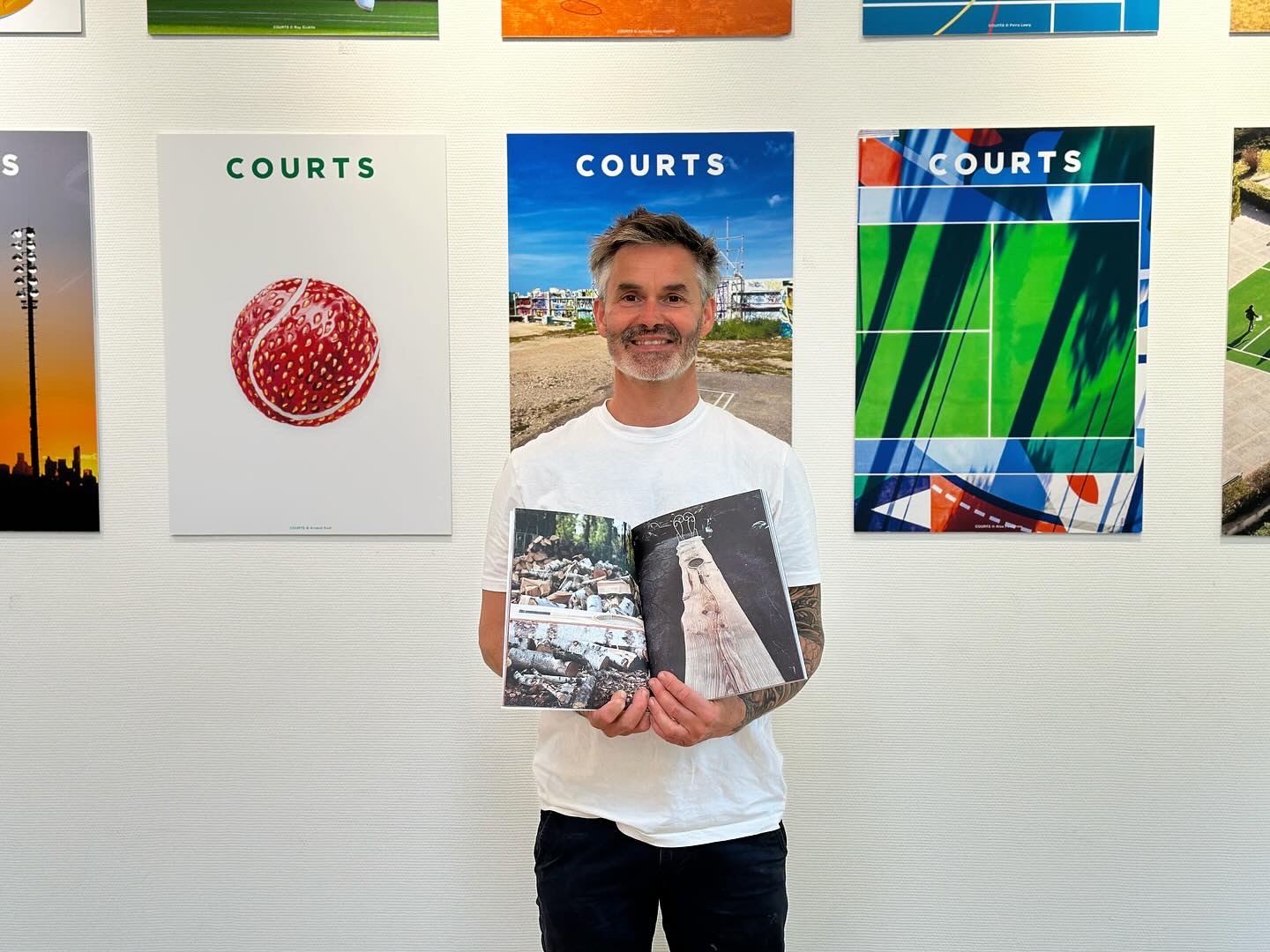

The agency’s top priority is to provide in-house expertise to each of its protégés. “We offer access to the world’s leading specialists in various tennis-related fields, say the two close founding partners of EDGE, Clément Ducasse and Daniel-Sacha Fradkoff. This ranges from racket customization and statistical/video analysis to biomechanics, mental preparation, and even the possibility of practicing on a recently installed London grass court in Switzerland.”

Wild Cards for Africans at the Orange Bowl

Despite its potential, the African continent has had very few top champions, excepting South Africa and Zimbabwe with the Black family (Cara, Byron and Wayne). This is why EDGE decided to get involved.

“We have an agreement with the Junior Orange Bowl, one of the most prestigious tournaments for talented youngsters. As partners, we organize qualifying tournaments for boys and girls in different parts of the world. Winners and finalists receive wild cards to the Orange Bowl’s U14 and U12 events held at the end of each year in Miami. We organize these qualifiers mainly in the Middle East, Africa, and Europe, although the need is less in Europe, as the best players from that continent are already backed by their federations or have the necessary ranking.”

The CAT, a Major Player in Africa

Since late 2023, the Confederation of African Tennis (CAT) has been led by Benin’s Jean-Claude Talon, whose goal is to develop African tennis on a global scale. This is evidenced by one of his first objectives: “placing several Africans in the top 100 of the ITF World Tennis Tour Junior Rankings.” As it happens, Africa only had seven representatives – mostly from the Maghreb region – among the top 200 juniors at the end of February 2024: four boys (Moroccan cousins Karim and Reda Bennani, Tunisian Alaa Trifi, and Egyptian Nour Fathalla) and three girls (Beninese Gloriana Nahum, Moroccan Malak El Allami, and Egyptian Jana Hossam Salah).

The robust plan devised by the CAT under Jean-Claude Talon’s enlightened leadership is multifaceted. It includes building facilities and creating academies, promoting tennis in schools, providing training for a wide range of coaches and referees, and ensuring the involvement of iconic players as role models. This ambitious yet realistic plan also envisions hosting several tournaments on the continent, such as the African Cup of Nations, the Orange Bowl, and a number of ATP & WTA 250/500 events.

Access to Tennis World Luminaries

“Tennis is deeply loved in Africa. There’s real potential there. To help develop the game, in addition to the Orange Bowl qualifying tournaments, there’s this idea of knowledge sharing. EDGE plans to connect with national federations so that families with gifted youngsters can seek assistance. We’re able to arrange for budding champions to meet our experts or find an academy if need be.”

“We don’t force them to leave Africa, clarifies Guillaume Ducruet, an EDGE agent. If they have a good training center or a qualified coach with efficient programs to support their development, all the better! Our goal is to identify promising champions, sometimes remotely, by giving them opportunities to compete in prestigious tournaments like Tennis Europe or the Orange Bowl, and to connect them with high-caliber coaches like Rick Macci or Riccardo Piatti,” two legendary figures whose training methods are highly sought after.

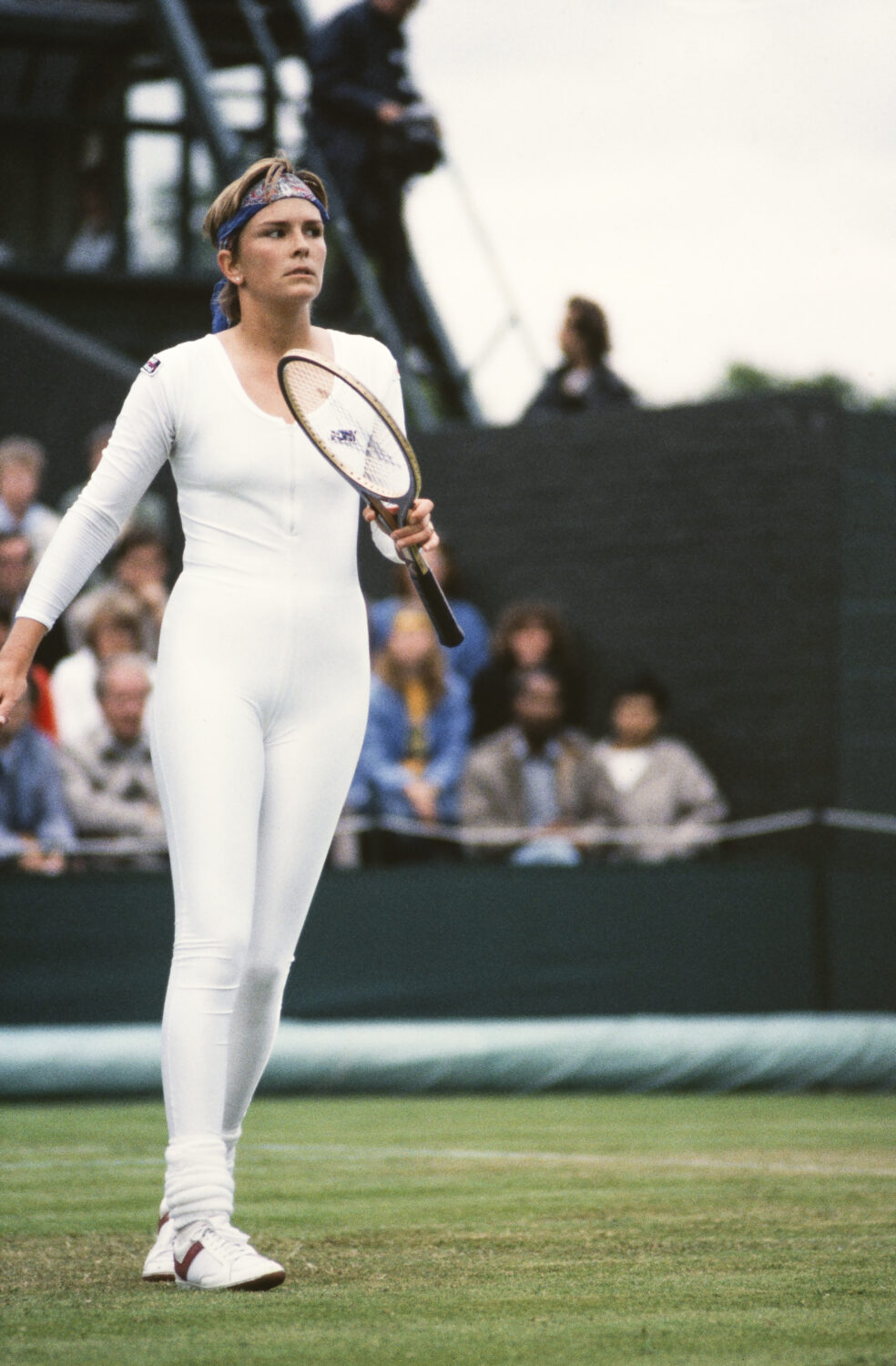

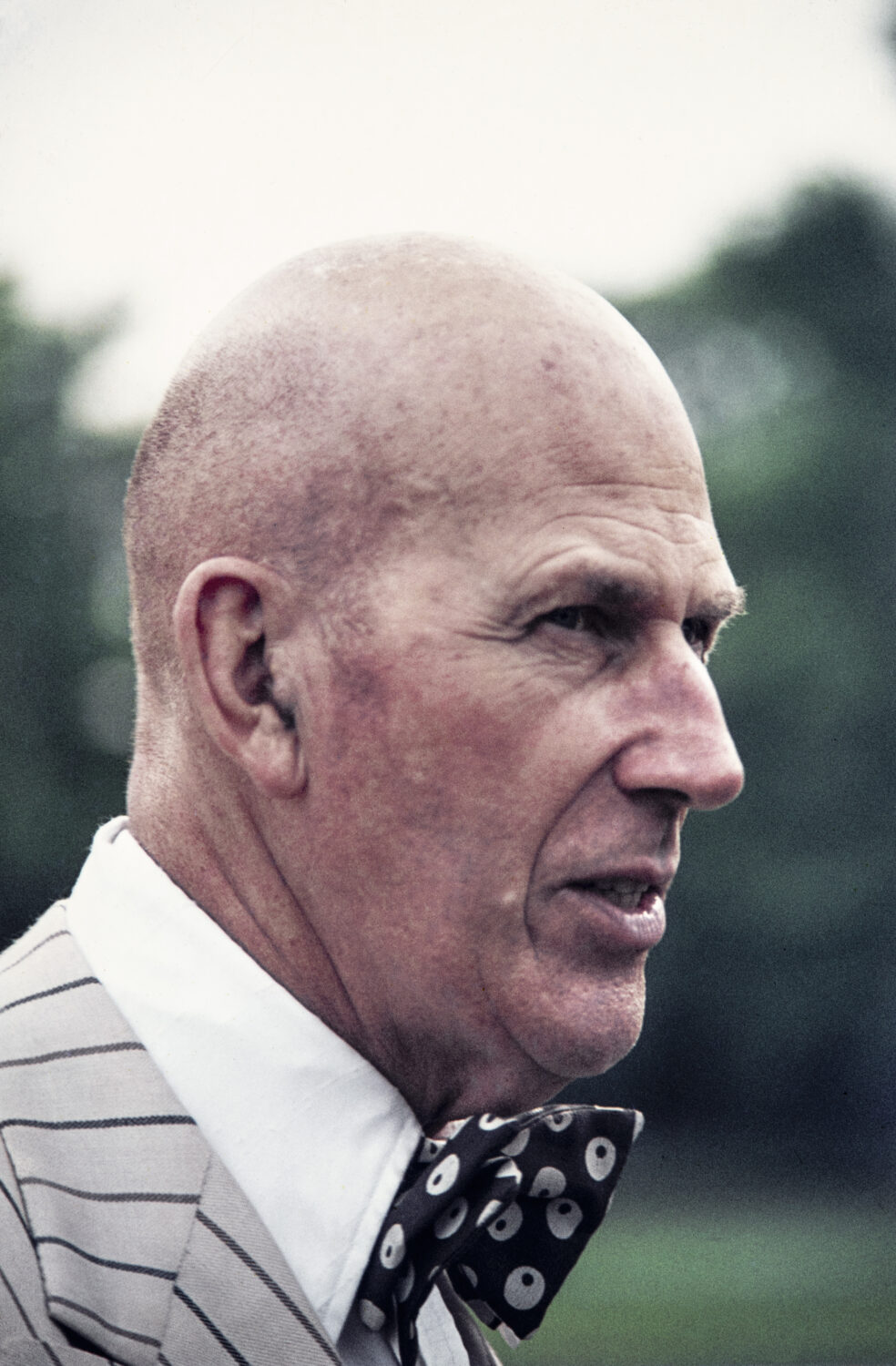

Rick Macci, who may be familiar from the movie King Richard, has a renowned academy in Boca Raton and is a cornerstone of EDGE. He’s known for nurturing the talents of prominent players like the Williams sisters, Jennifer Capriati, Andy Roddick, and more recently, Sofia Kenin. “For instance, Ducruet continues, young players going to the Orange Bowl will have the chance to train with Rick Macci at his facilities. He also provides remote video coaching for our players and their entourage on the technical aspects, particularly biomechanics – he’s an absolute master in that area! But there are also opportunities to work with Daniil Medvedev’s coach, Gilles Cervara, who serves as a consultant and ambassador for EDGE.”

As for Riccardo Piatti, he has dedicated his coaching skills to Ivan Ljubičić throughout the latter’s career, Novak Djokovic between 2005 and 2006, and players like Milos Raonic, Richard Gasquet, as well as Jannik Sinner during his formative years (ages 12-20) among many top Players over the years. “We have a partnership with his academy, the Piatti Tennis Center, located in Bordighera, right next to Monaco, explains Luca Bassi, an EDGE partner with close ties to the Italian coach. We offer resources that the academy might lack, and in return, they send some players and coaches to our campus in Switzerland. Some of our players might spend a week or even a year training there. This allows us to provide opportunities for young talents who lack proper infrastructure in their home countries. But we don’t restrict their choices. If players have a valid reason to join another academy, we won’t stand in their way. We don’t impose anything. These young athletes are in charge of their own career paths; we’re simply there to support them.”

Aziz Dougaz: Embodying the ‘Africa Project’

Although the ‘Africa Project’ was still in its infancy at the beginning of this year, EDGE already had a player embodying its spirit: Aziz Dougaz. As of 27 February 2024, at the time of writing this article, the 26-year-old Tunisian held the #218 spot in the world, making him the top African player and the Arab champion at the end of 2023. He grew up with a dream of forging his own path in tennis, something no one in his country had done before him. Prior to 2017, no Tunisian player had managed to crack the top 50 in singles (though Selima Sfar did reach #75 in 2001). Then came Malek Jaziri, who broke the barrier 15 years later, peaking at #42 in 2019. Ons Jabeur followed suit, entering the world’s top 50 in 2020 and eventually cementing herself as Tunisia’s greatest player ever, reaching three Grand Slam finals and achieving a WTA ranking of #2 in 2022.

“Being young definitely creates a lot of mental limitations, Dougaz stated on the YouTube channel Game, Set & Talk at the beginning of 2024. Most of the time, the people around you don’t believe it’s possible. When you start playing tennis in Tunisia, envisioning yourself among the top 50 or 100 players in the world is an unattainable dream. But thanks to the achievements of Ons Jabeur and Malek Jaziri in recent years, the Tunisian Tennis Federation now has more resources available. Yet, growing up remains a challenge. You look around and realize that most players quit tennis at 15-16 to focus on their studies. It isn’t ingrained in the mindset of players or their parents to take a chance and believe in the dream. In my case, it was more like, ‘Aziz, why are you trying to become a professional tennis player? You’d be better off focusing on training to be a doctor, lawyer, or engineer. There’s no future in tennis. Don’t think it’s going to be any different for you.’”

Thanks to his relentless determination and unwavering parental support, Aziz Dougaz, the powerful-serving, left-handed Tunisian, has already achieved the significant milestone of becoming a professional tennis player. “My family isn’t involved in tennis, he confided, so they were taking a leap of faith too. I recently told them that they were a little crazy! They didn’t know anything about tennis but they believed in me although I was barely 15. It wasn’t a logical decision for them to take. It’s truly incredible how lucky I was that they believed in me with no knowledge of the game, no facilities, no experienced coach – nothing. Yet, we’ve managed to progress step-by-step despite the numerous obstacles.”

Like an explorer venturing into uncharted territory, the native from La Marsa had to forge his own path, lacking the machete a well-funded federation could have provided to clear hurdles more quickly. In 2015, at the age of 17 and a ranking of #45 in his age group, he embarked on a solo journey – without a coach or any other form of assistance – to compete in the Australian Open juniors on the other side of the world. Subsequently, he decided to follow the college tennis path in the US to launch his professional career. But his first experience with a full-time coach only came in 2023, and it was with Yannick Dumas, a member of the EDGE team.

“Having all these resources at my disposal allows me to learn faster,” says Aziz Dougaz.

“Before joining EDGE, I had two coaches, explains Aziz Dougaz. The first was from Brazil. We worked together for three months but had to stop in March 2020 due to Covid. After that, he turned his focus to creating an academy and it wasn’t possible for me to continue working with him. Then, right before joining Yannick, I spent six months with a Portuguese coach who had to stop due to health problems, something we both regretted. So yes, with Yannick, it’s definitely the first long-term collaboration for me – it’s been a year already.” The coach is a benefit provided by EDGE, just like the other experts – physical trainer, mental coach, nutritionist, racket customizer, statistician, stringer, and osteopath – available at the Swiss campus as well as on the tour itself.

“The expertise and skills offered by EDGE are typically something only top 100 players can access,points out Yannick Dumas, unless they come from well-funded federations like the FFT. Young Argentinians or Slovenians, for instance, are unable to enjoy such benefits. Yet, we’re offering them through the ‘Africa Project’. Data and performance analysts like Fabrice Sbarro and Shane Liyanage scrutinize the strengths and weaknesses of our players as well as their opponents. Only the best can afford such resources. Fabrice has worked with Gilles Cervara for years, and more recently with Top 20 ATP and WTA players; Shane works with Aryna Sabalenka and Ons Jabeur, among others.”

For Aziz Dougaz, this has been a journey into a new world, where he has had to learn a great deal independently, crafting his own tools for progress, sometimes making painful mistakes in the process.“My starting point was very low compared to the resources, knowledge, and tennis environment most players enjoy, he revealed. I only started customizing rackets a year ago, even though everyone else had been doing it since a very young age. Physical preparation was the same. Before, my training was random and improvised – intermittent work at best. As for mental training, I had never really worked with a specialist in this field before. Had I benefited from all this knowledge when I was younger, I would have avoided a lot of mistakes. However, going through so many trials and tribulations with my family made me stronger. And having these resources at my disposal now allows me to learn faster.”

Yannick Dumas: Aziz Dougaz’s Coach and Driving Force Behind EDGE’s Project

Yannick Dumas has been supporting Aziz for quite some time. “He came to France when he was 15, looking for a training structure for a year, recalls the French technician. He and his family were at a crossroads – either stay in Tunisia, where tennis is challenging, or go to an academy. I was coaching the girls’ program at the academy he visited. We’ve kept in touch ever since, always talking about working together, but it never happened. In January 2023, I returned from Australia after my collaboration with a Canadian player came to an end. Aziz called me, explaining that he had several tournaments lined up and had just parted ways with his coach owing to the latter’s health problems. He asked me if I’d be interested in teaming up with him. Since then, we’ve continued working together week by week. It was during this time that I also started discussions with EDGE, and in March, I officially joined the agency to help develop the ‘Africa Project’.

Yannick’s involvement in the ‘Africa Project’ stems from his passion for the Black Continent, where he has garnered extensive experience. As a young coach, he spent a lot of time in Africa working at junior ITF tournaments. “Over the years, I got to know the tournament organizers, facility managers, and many others, he recalls. I fell in love with Africa and its people. I met talented kids with a boundless desire to learn, become champions, and give their all. Unfortunately, they had very few resources, if any. I helped some players, including a young Ethiopian for a few months, taking them to tournaments and so on. Given EDGE’s human and financial capacities, we wondered how we could best support this continent yearning to develop. Aziz, the inspiring story of an African who made it on his own, could be the mentor, the driving force for future generations. He’s currently the #1 ranked African and Arab player in the men’s category.”

However, the role of Aziz extends beyond mere mentorship. “He is much more than a mentor, Yannick Dumas adds, he also helps me think strategically. We discuss the ‘Africa Project’ and how to build it together. He has shared with us his insights on how things work in Africa, drawing on his extensive first-hand experience there. With his knowledge, he’s become a co-architect of the project.” Aziz Dougaz, who still lacks a sponsor and has to rely on the assistance of EDGE and the Tunisian Tennis Federation, doesn’t play solely for himself. His goal of reaching the top 50 is also driven by a desire to create more resources and empower other players.

“I’ve always believed that a true champion is defined by more than just on-court performance. The first quality of a champion, or anyone who succeeds in life, for that matter, is the ability to give back and help others, he says. These values, instilled by my parents, have always been important to me. Helping young people and passing on knowledge is something I truly care about. If, through my experience and with EDGE’s support, I can help young players avoid the mistakes I made, that would be incredible. Moving up the rankings would allow me to provide greater support and have a more significant impact on them. It’s a dream I’ve always held close.” Not surprisingly, he’s already moved from words to deeds by introducing Yannick Dumas to a promising 14-year-old Tunisian player, also left-handed. “We’re sharing Aziz’s experience with him and his family, Yannick explains. We’re answering their questions about building a career. And then, if we’re all in agreement, we could offer him additional resources such as coaching expertise or occasional trips to Europe.”

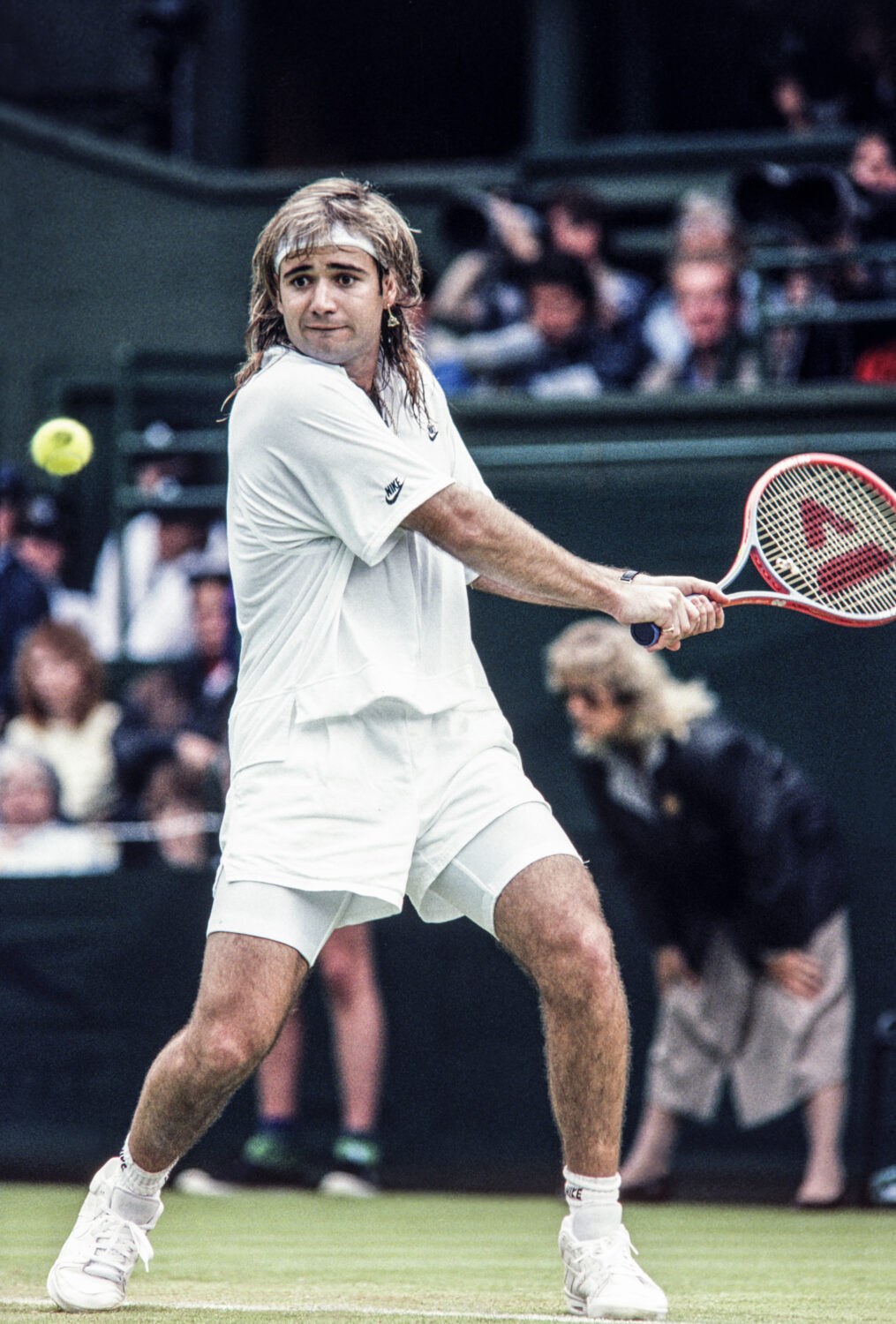

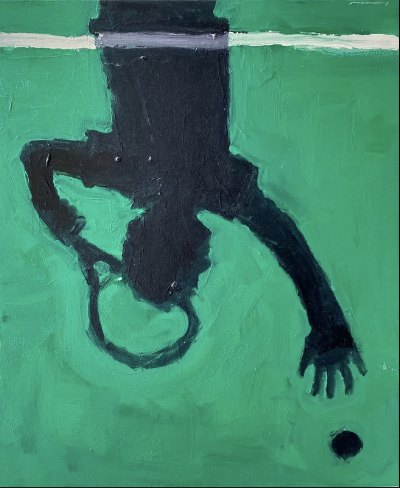

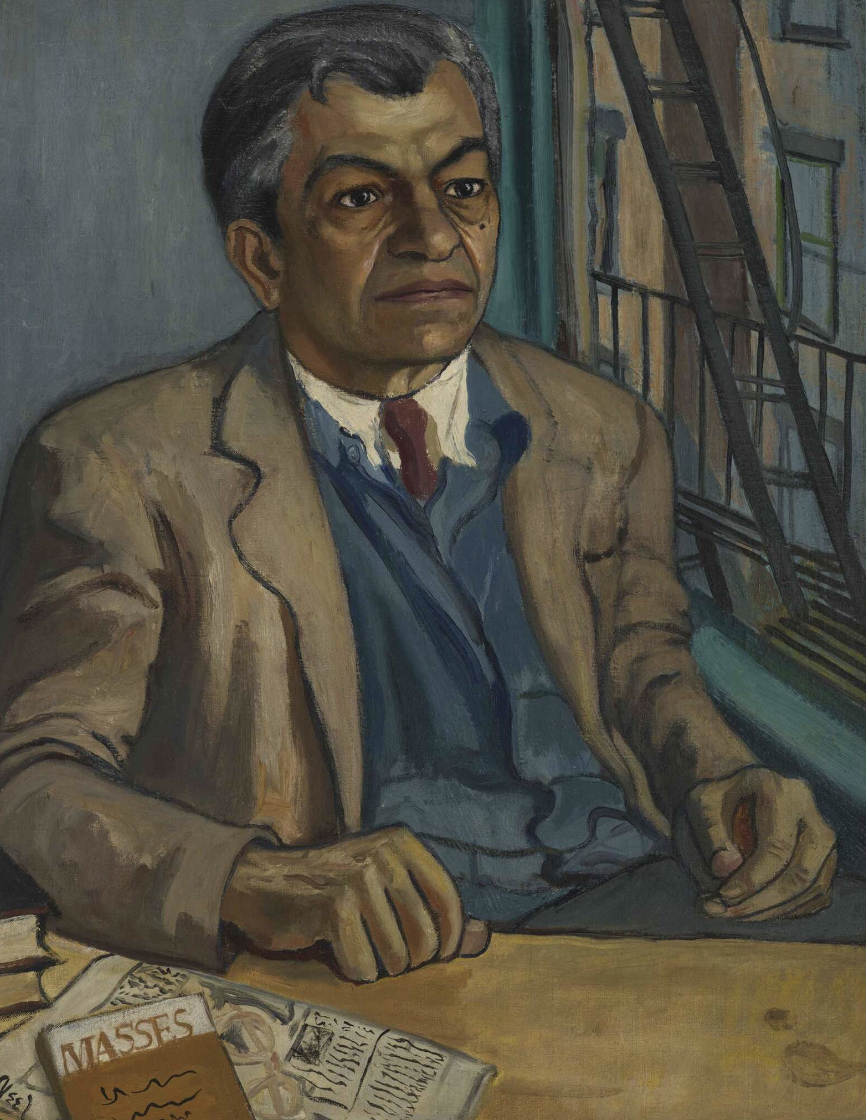

EDGE is keen to “multiply these experiences with African players” as part of a broader effort to find successors to the only two black African players to have won a singles title on the main circuit:

![]()

Don’t grumble: there’s nothing wrong with Mickey Mouse Magazine!