Vienna, Freud’s “City of Dreams”

Who’s coming with their mental coaches for the Erste Bank Open?

[Take me there]

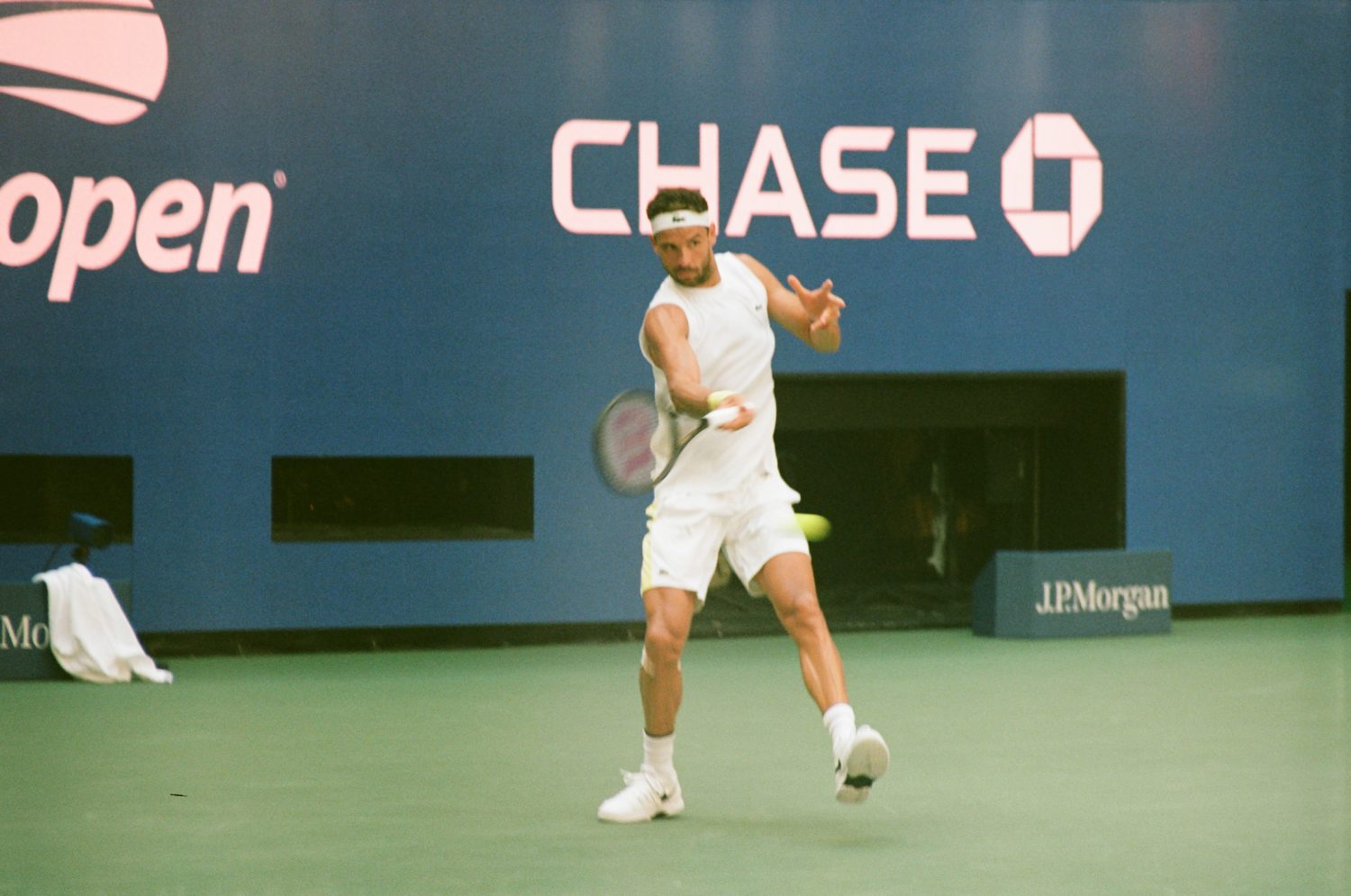

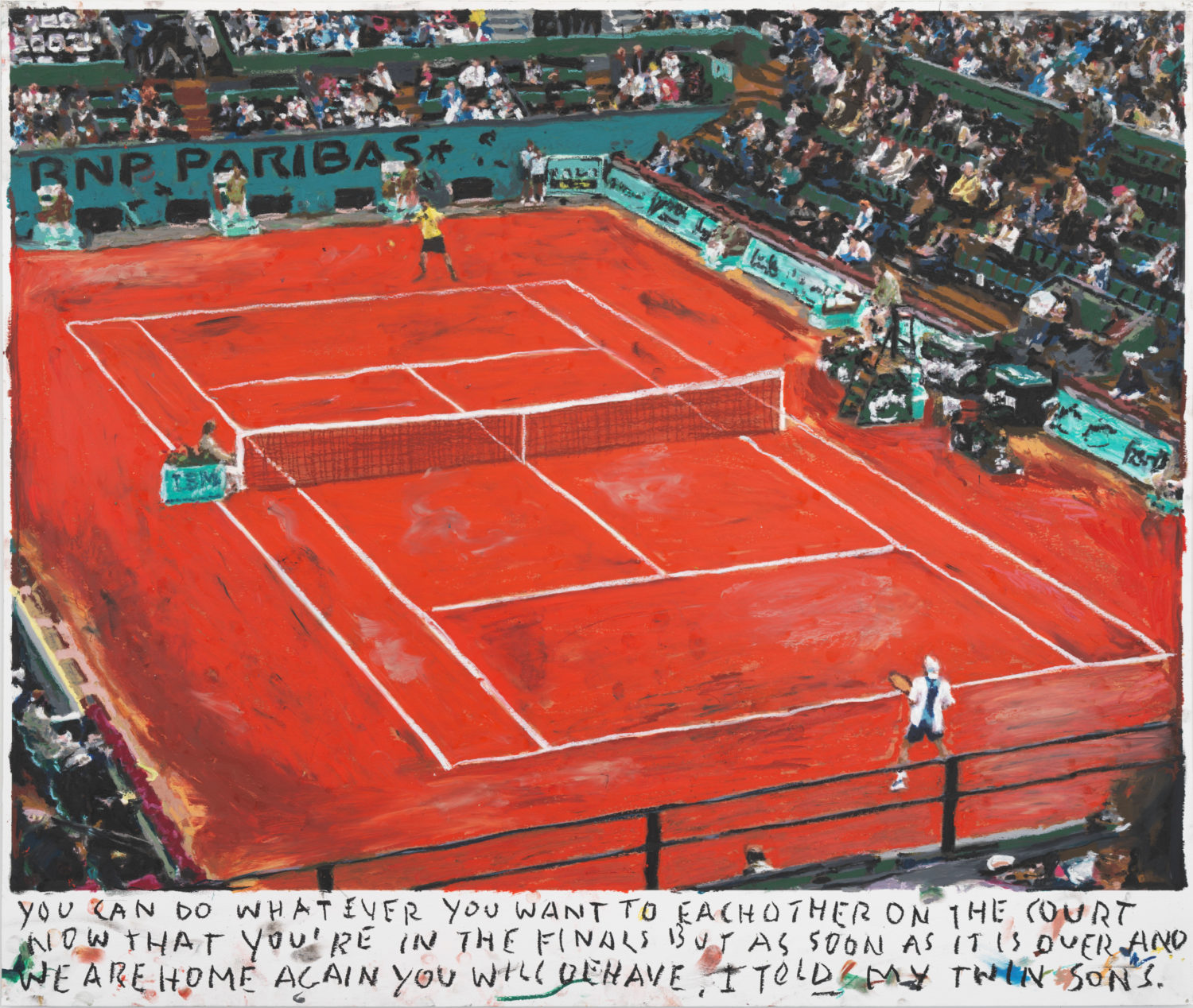

Vienna, long a European capital city and centre of psychiatric advancement, has a few surprises up its long and windy roads, including a thriving tennis scene. Long the home of Dominic Theim, the former top Austrian player, and up-and-comers Sebastian Ofner (ATP No. 49, Austrian No. 1), Jurij Rodionov (ATP No. 100), and Filip Misolic (ATP No. 179), Austria can also count legends, such as Thomas Muster, Jürgen Melzer and Barbara Schett among its tennis royalty. While Theim and Ofner both got wild cards into the 2023 Erste Bank Vienna Open, it will be a tough draw for the hometown favourites, since Jannik Sinner, Andrey Rublev, Dan Evans and Ben Shelton — fresh from hot streaks at the Rolex Shanghai Masters — have all scheduled appearances in Vienna. The Vienna Open which started life in 1974 as the Stadthalle Open, in homage to its home, The Stadthalle, is an ATP 500 event, just one notch down from Shanghai and next month’s Rolex Paris Masters, as the players try to cram in as many possible rankings points before the season ender in Turin. Surprisingly, American Brain Gottfried is the Vienna’s Open winningest player, with four conical gold trophies in his case. .

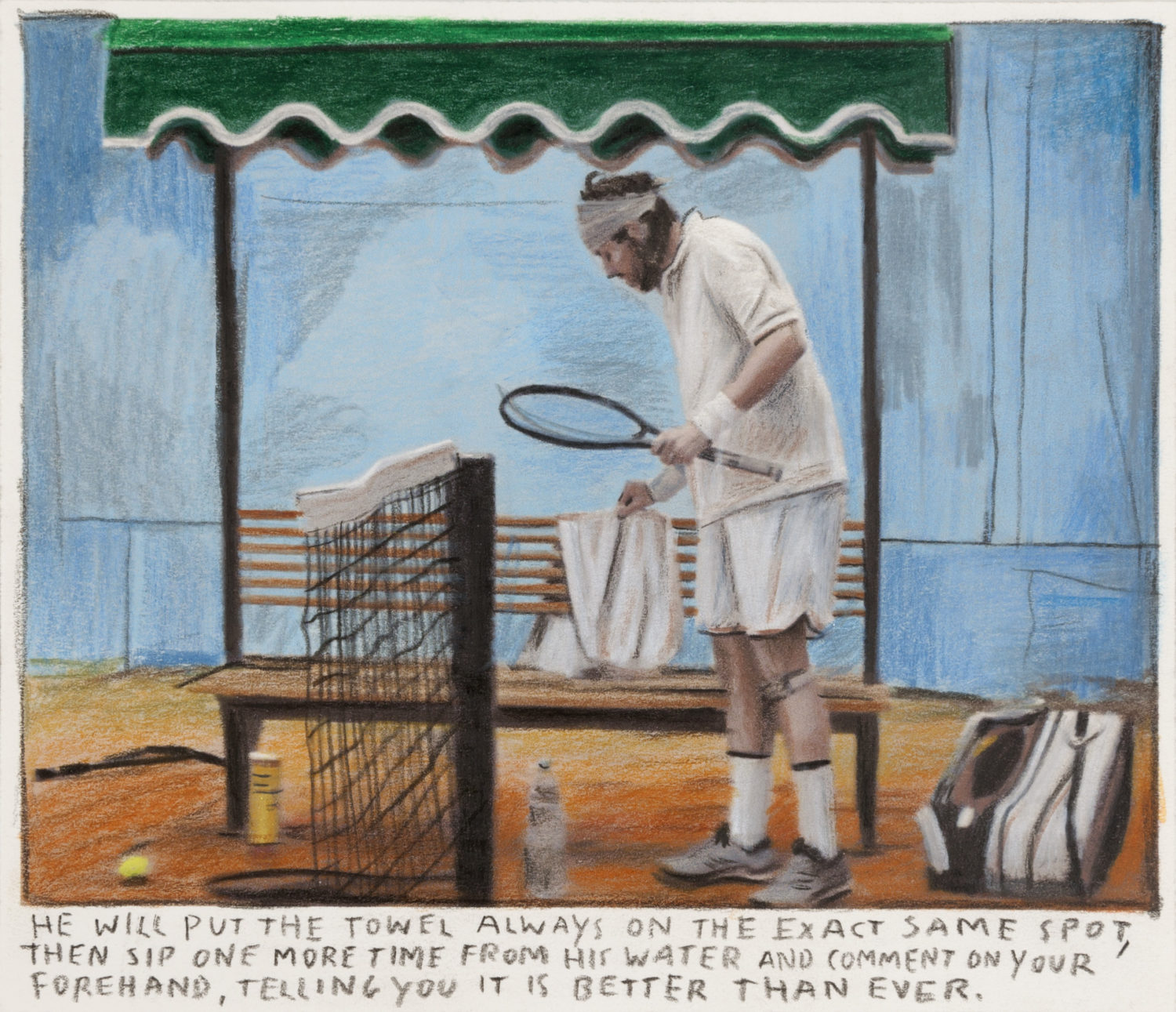

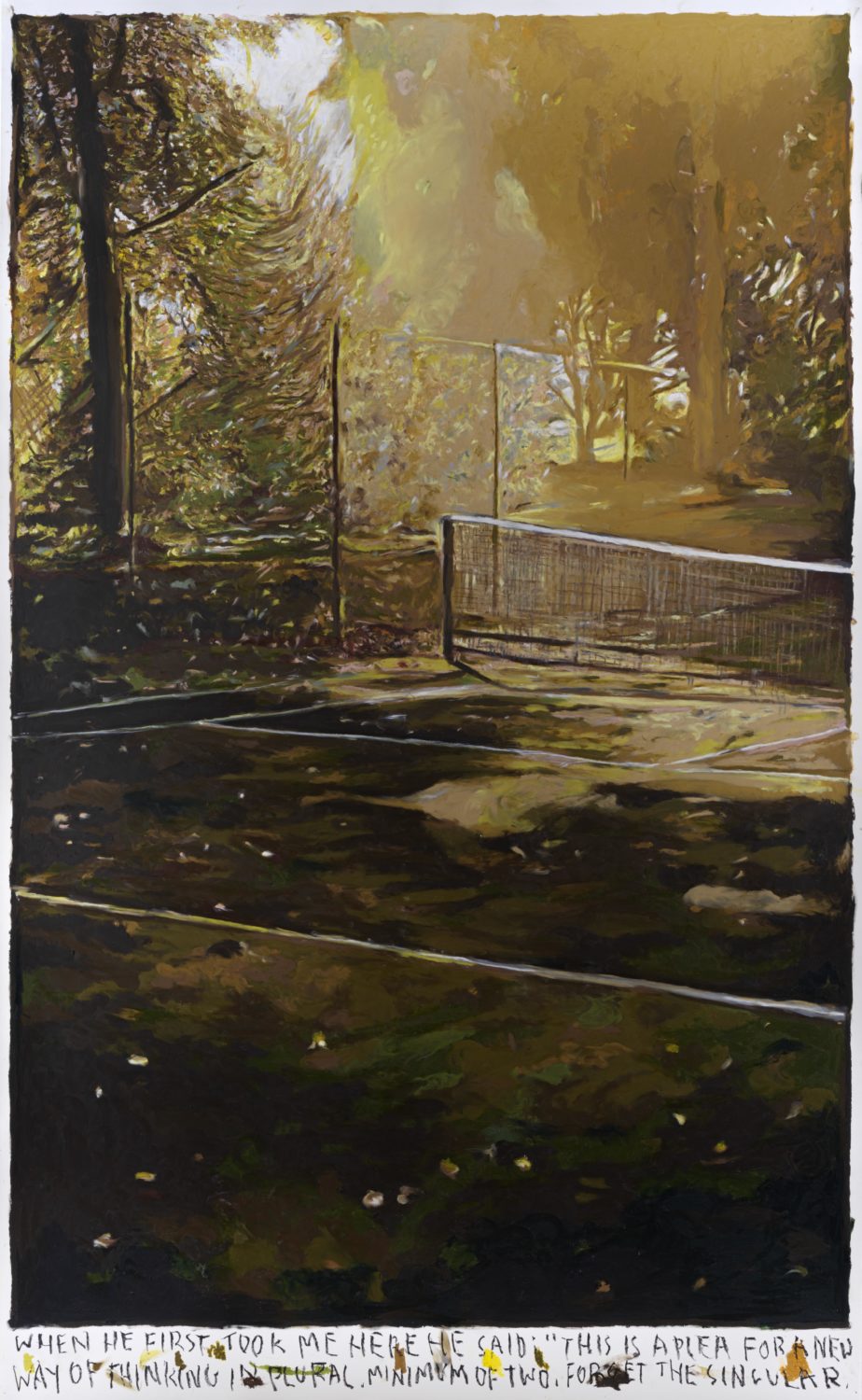

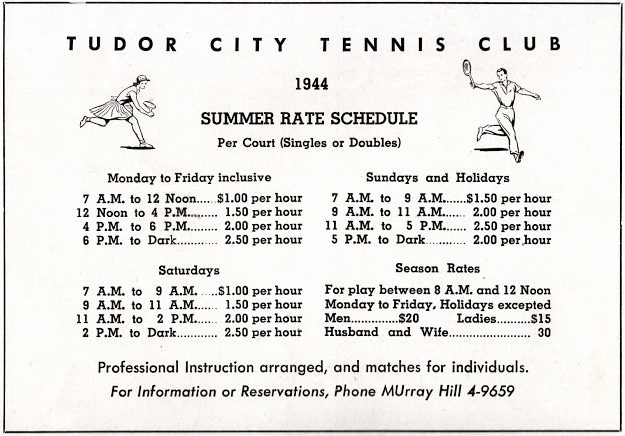

Vienna Tennis Clubs

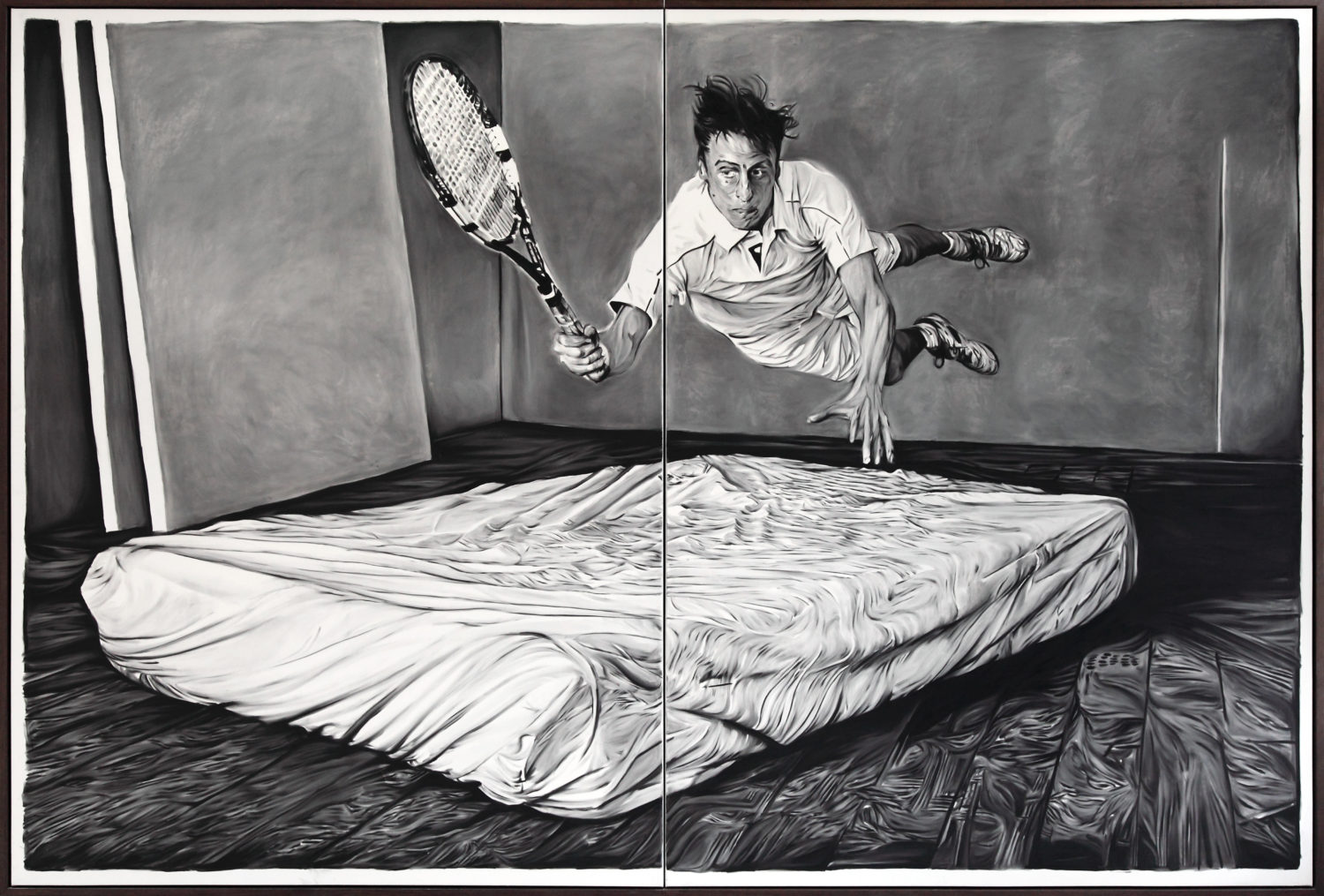

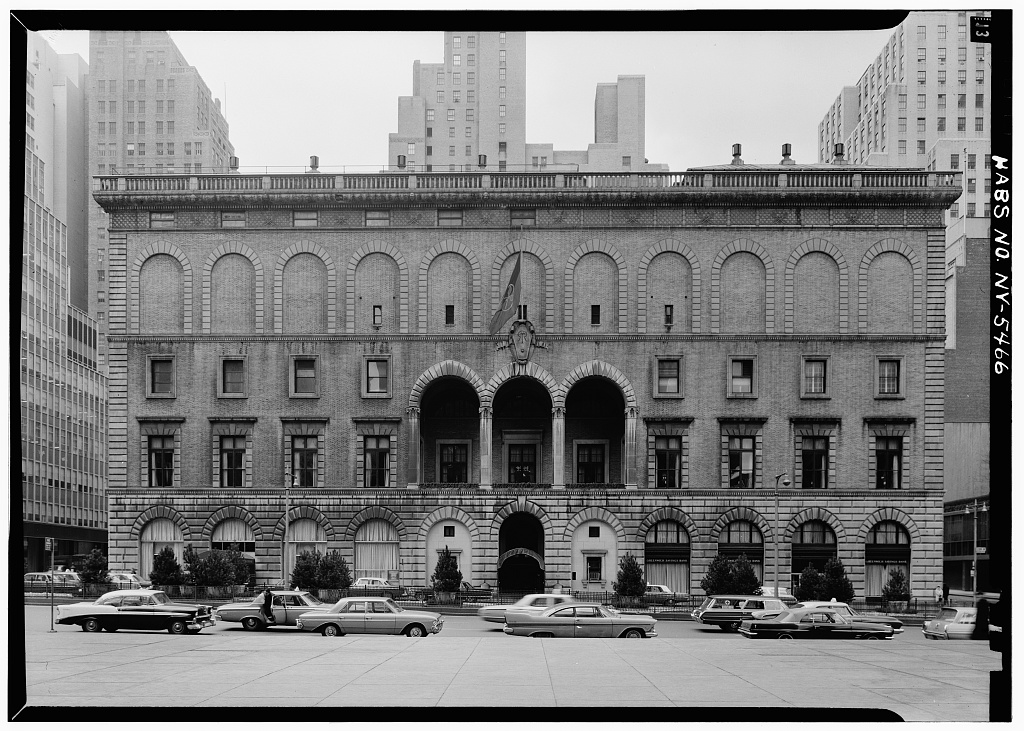

While the Wiener Stadthalle is the official venue of the Erste Bank Open, Vienna has a rich tradition of tennis that reaches out to all disparate groups, including the United Nations VIC Tennis club, the Heeres-Tennis Club Wien and the Arsenal Vienna Tennis Center. Designed by the decorated Nazinarchitect Roland Rainer in 1953, the multi-purpose venue is Austria’s largest indoor arena and has a seating capacity of approximately 16,152 people. Just across the river at the Vienna International Centre, however, the VIC Tennis Club — a club whose members are almost exclusively Vienna-based United Nations employees — runs several groups per week and monthly tournaments on its clay courts — no doubt the site of some global dealmaking, as well. Meanwhile, just on the outskirts of the old city, the great hall of the HTC-Wien features four roofed tennis courts and training that covers “moves and tactics” for better play. Lastly, the courts of the Arsenal Vienna Tennis Center stand in the midst of the historic Vienna Arsenal complex used by groups aiming to create Austria as a nation state in the late 19th century.

Must See in Vienna: a Day in the Life of Mental Coach Sigmund Freud

Of course, Sigmund Freud was at modern Vienna’s intellectual and even cultural nexus, and his apartment at Berggasse 19, where he stored some of his most precious art and artefacts, picked up on his daily constitutional around Ringstrasse — Vienna’s grand, tree-lined boulevard. Often lapped by a young Adolf Hitler, an embittered artist of meagre talent turned down by the Vienna Academy of Art, Frued would often stop at Kunst Historisches Museum, a treasure trove of Egyptian, Greek and Roman art now containing works from Dürer to Vermeer, as well as the world’s largest collection of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the chronicler of the play between psychiatry and morality. On the way back, often with a new antiquity in hand, Freud would peruse the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek — formerly the court library to the Hapsburgs — and its extraordinary collection that dates back to the 14th century. He could also ponder his own fate at the Kapuziner Gruft (Habsburg Imperial Crypt) — the final resting place for the remains of 143 Habsburg royalty, who controlled the Holy Roman Emperors from 1438 to 1740 and were avid sponsors of Real Tennis. It showcases an impressive collection of Vienna’s signature memento mori, which even have their own festival.

Shop

Although he prescribed the intense, inner journey of psychoanalysis for the wealthy worried of Vienna, Sigmund Freud’s own remedy was retail therapy —the shrink was also a bona fide shopaholic. One of Frued’s favorite passtimes was strolling through the Innere Stadt, the labyrinth of medieval streets at Vienna’s heart, where he stocked up on cigars and surveyed the shops of antiquities’ dealers. Today, the Dorotheum, one of the world’s oldest auction houses, has a nearly daily auction of everything from watches to classic cars. Next, nine floors of luxury clothing and design await at the Steffl Department Store, known to locals at the Steffl. A quick sugar high awaits at Viennese confiserie and chocolaterie, Altmann & Kühne, which fortifies shoppers for a stop at Augarten for a personal collection of porcelain once reserved for royalty. Lastly, for items to put in those fine dishes, Julius Meinl am Graben is the most famous supermarket in Austria, featuring a delicatessen with meats, cheese, coffee and chocolate from around the world.

Eat, drink and make merry

Freud, very much a man of habit, ate his daily meal at precisely 1pm with a menu, prepared by his wife, Martha, to cater to Freud’s taste: a juicy cut of beef and seasonal vegetables. Apfelstrudel with a dollop of cream followed the meal, before an afternoon seeing clients. But the modern Viennese would frown on Frued’s singularity, especially with all the fine dining around. Renowned for its schnitzel, particularly the Wiener Schnitzel (breaded and fried veal or pork cutlet), Figlmüller is a must-visit for traditional Austrian fare. To try some more inventive Austrian cuisine, Steirereck, a Michelin-starred restaurant located in Stadtpark, offers such dishes as Amur Carp with Fennel, Sea Buckthorn & Viennese Malt or even Sunflower with Curry Plant, Yoghurt & yellow Beans. Motto am Fluss along the Danube Canal, has a menu with a mix of international and Austrian dishes, along with a great view of the river. To wrap things up, Café Central with its elegant ambiance and traditional Viennese coffee and cakes helps acquaint any guest with the city’s café culture.

Sleep

Freud was never rich but he was not afraid to spend money, saying “the filthy lucre runs through my fingers at such frightening speed.” Patients were stunned when ushered into his rooms at Berggasse 19, feeling he was not in a doctor’s office but an archaeologist’s study surrounded by “all kinds of statuettes and other unusual objects.” While hotels in Vienna may not offer such personalised accommodations, the Hotel Imperial, originally built as a private residence of Duke Philipp of Württemberg, is located near the Vienna State Opera and other major attractions. More modern luxury awaits at the Grand Ferdinand Vienna, a chic hotel with a rooftop pool, trendy rooms and a spa. Motel One Wien-Staatsoper is a stylish budget-friendly option, while the more eco-friendly might go for Hotel Daniel Vienna with its rooftop beehives and garden near Belvedere Palace.