He was born to an aristocratic noble family in Czarist Russia, but his best-known novel, Lolita, captures the quintessential post-war United States, a very tawdry side of it. The setting and milieu of the brilliant, funny — and scandalous — book that made the name “ Lolita ” recognized by all are at complete odds to the elegant St. Petersburg in which Vladimir Nabokov grew up, but two core elements are essential to both worlds. They are universal passions that transcend issues of location or wealth or background. One is sexual lust. Another is the sport of tennis.

Humbert Humbert meets the teenage girl who will obsess him to delirium when he decides to progress from living in “ prefabricated timber cabins ” with “ chemical toilets ” to a rooming house run by the mother of the nymphet whose name has become a household word. He is appalled by the tackiness of his new digs at first glance, the clutter of objects he describes as “ Mexican trash in a corner cabinet ” and the like. Born in Paris to a father of Swiss, French, and Austrian blood and an English mother, when he enters that hideous house, he needs, to steady himself, “ to stare at something. ” The single reassuring object on which he can focus is “ an old gray tennis ball that lay on an oak chest. ”

No wonder it calms him. The fuzzy sphere — in the 1950s, when this scene takes place, it would have been felt-covered rubber, white before it grayed, in the era before today’s bright yellow was even considered — was the one thing in the house familiar to him, since as a boy growing up at an English day school on the French Riviera, where his father ran a fancy resort hotel, he had played tennis. In France in that earlier epoch, the ball might well have had a nucleus of cork and been wrapped in wool. But, still, the size and shape of the tennis ball in Lolita’s mother’s house were a comfort to him, to the racy Humbert, providing the one link to his own past.

Rereading Lolita even if only to find the tennis scenes again, you might still be as shocked as people were when the novel came out in America in 1956. Humbert is as fired by desire as just about anyone in the history of literature, troubling even the most liberal of readers because of the age of the girl he has taken from her home on a journey where they tryst amorously in motel after motel across the American landscape. He hides nothing about his “ dazzling romps. ” Even the way he decides to teach his inamorata tennis and other sports as if to give her a chance of normalcy has a twist. When we see “ Lo on horseback ” and then in a chairlift at a ski lodge, she is sheer allure. Although Humbert acts as if he cares only for the girl’s education and her becoming a well-adjusted young woman, every time he introduces her to a new sport, it provides him with a new vantage point of the body for which he chronically lusts. “ I freely advocated whenever and wherever possible the use of swimming pools with other girl-children. ” This gives him a chance to leer: “ There I would sit, with … nothing but my tingling glands, and watch her gambol … smoothly tanned, as glad as an ad, in her trim-fitted satin pants and shirred bra. Pubescent sweetheart! ” But tennis is the sport that, more than any other, is vital to the love of Humbert Humbert for Lolita.

Humbert, “ a good player ” in his prime, decides to teach the teenage girl “ to play tennis so that we might have more amusements in common. ” But, a “ hopeless ” teacher himself, he pays for “ very expensive lessons with a famous coach, a husky, wrinkled old-timer, with a harem of ball-boys. ” Those of us who have had tennis lessons in offbeat places can picture the “ awful wreck ” of a formerly great tennis player, even though few of us are old enough or rich enough to have been taught by anyone who had all those ball-boys. When Nabokov describes Lolita’s costly pro showing how good his forehand once was, we see just how well the high-spirited writer knew the game of tennis: “ He would put out as it were an exquisite spring blossom of a stroke and twang the ball back to his pupil. That divine delicacy of absolute power made me recall that, thirty years before, I had seen him in Cannes demolish the great Gobbert! ”

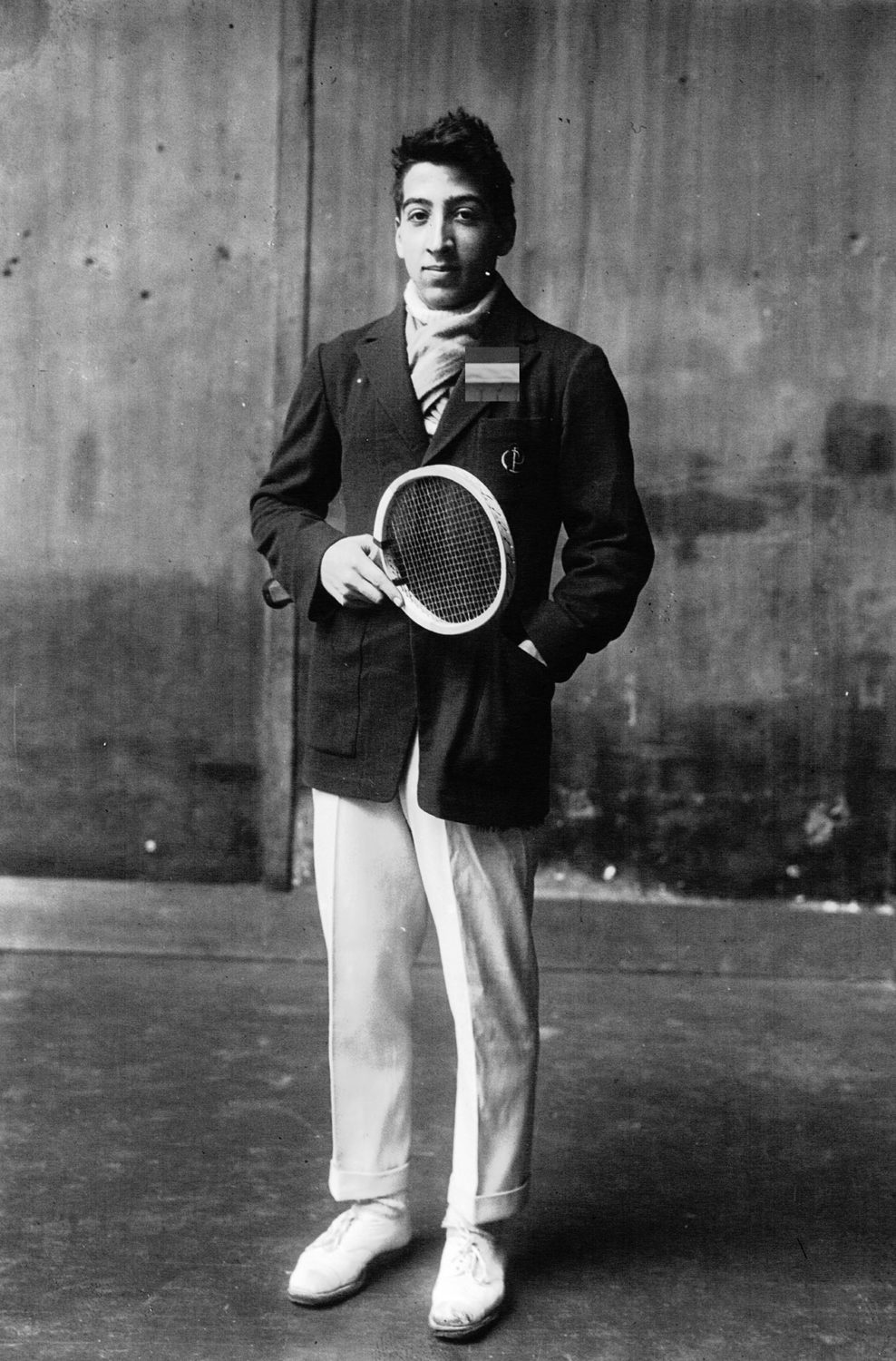

This is both as good a description of a winning shot as has ever been written, and an evocation of the world of tennis where a retiree in California can still hit the ball the way he did when he beat a giant on the French Riviera three decades earlier. André Gobbert is real, a splendid dose of actual history in a masterpiece of fiction; a Parisian, he won the French Championships in 1911 and 1920 when you have to be a member of a French tennis club to play. Picture him holding four wooden rackets, smiling at the camera in his boldly striped jacket over his whites - long white trousers, of course - which is how he sported himself when he won Olympic medals as well as the International Lawn Tennis Federations’s World Covered Court Championship in 1919. It is with tennis that Nabokov triumphantly links that world to middle America.

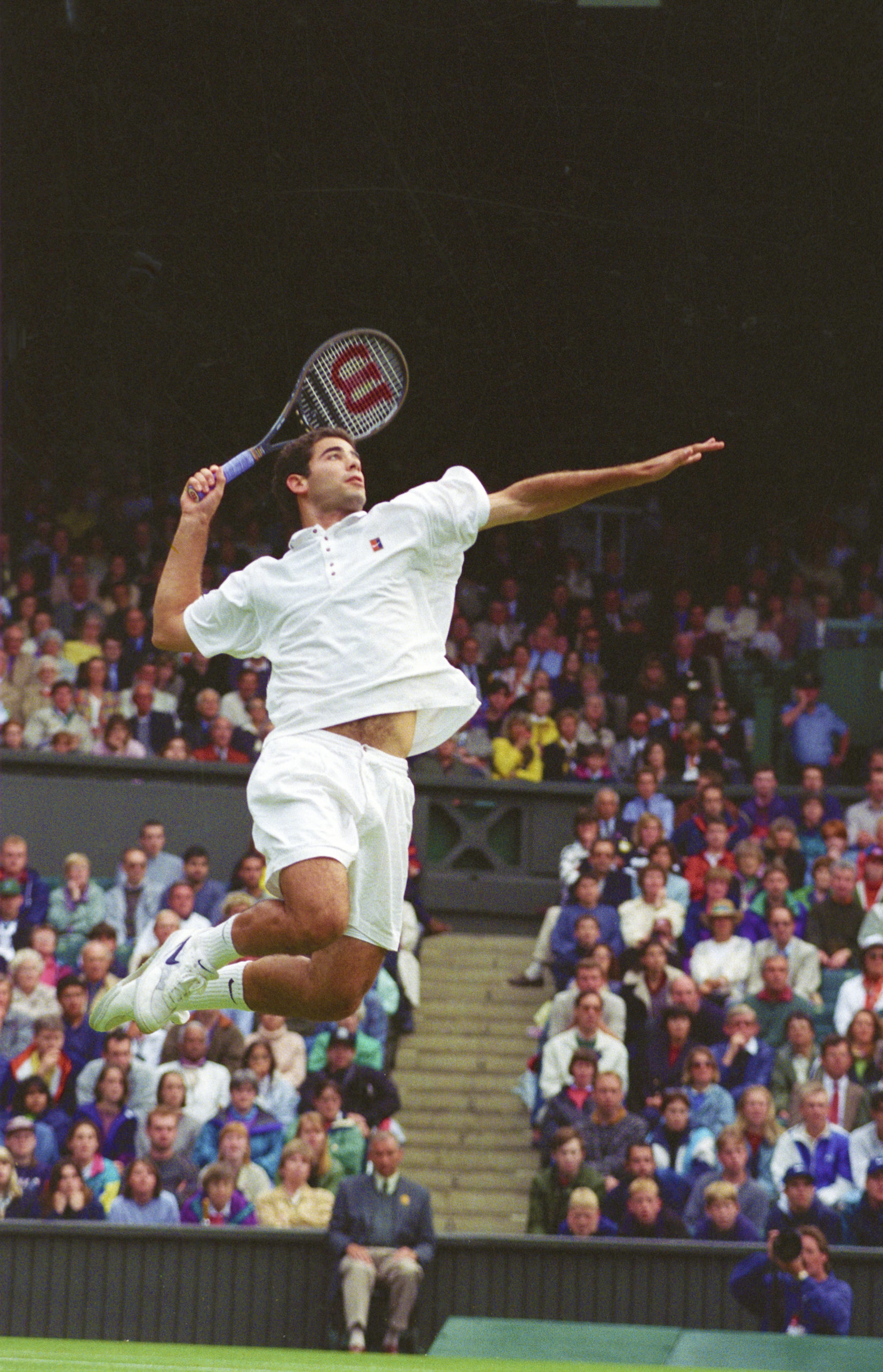

Other sports appear only once in the novel; tennis is a leitmotif. We see Lolita play it in California, southern Arizona, and, ultimately, in a typically Nabokovian invention: a “ Colorado resort between Snow and Elphinstone. ” This time the tennis scene is told as a memory, after Humbert’s illicit girlfriend has freed herself from him forever. Of all the ways Lolita gets described in this novel that is in fact sheer fantasy - not the ramblings of a dangerous pedophile but the quirky musings of a brilliant writer intoxicated with language and with human reach, within the safe confines of one’s mind, absent any agenda of real danger — the images of the beguiling teenager playing tennis the last time he saw her on the court epitomize all that obsesses him. If you fear the eroticizing of tennis, and mistake inventive and larky flights of thought for actual perversion, don’t read on. But if you can enjoy it as the stuff of humor and imagination, and as unequaled linguistic virtuosity, as skillful and magical as one of Roger Federer’s backhands that exceeds all expectations of the possible, continue:

She was more of a nymphet than ever, with her apricot-colored limbs, in her sub-teen tennis togs ! … the white wide little-boy shirts, the slender waist, the apricot midriff, the white breast-kerchief whose ribbons went up and encircled her neck to end behind in a dangling knot leaving bare her gaspingly young and adorable apricot shoulder blades with that pubescence and those lovely gentle bones, and the smooth downward-tapering back. Her cap had a white peak. Her racket had cost me a small fortune!

I don’t know about the rest of you, but I cannot picture the cap; on the other hand, I totally understand the jump from reverie to the distress over what one has spent on a tennis racket.

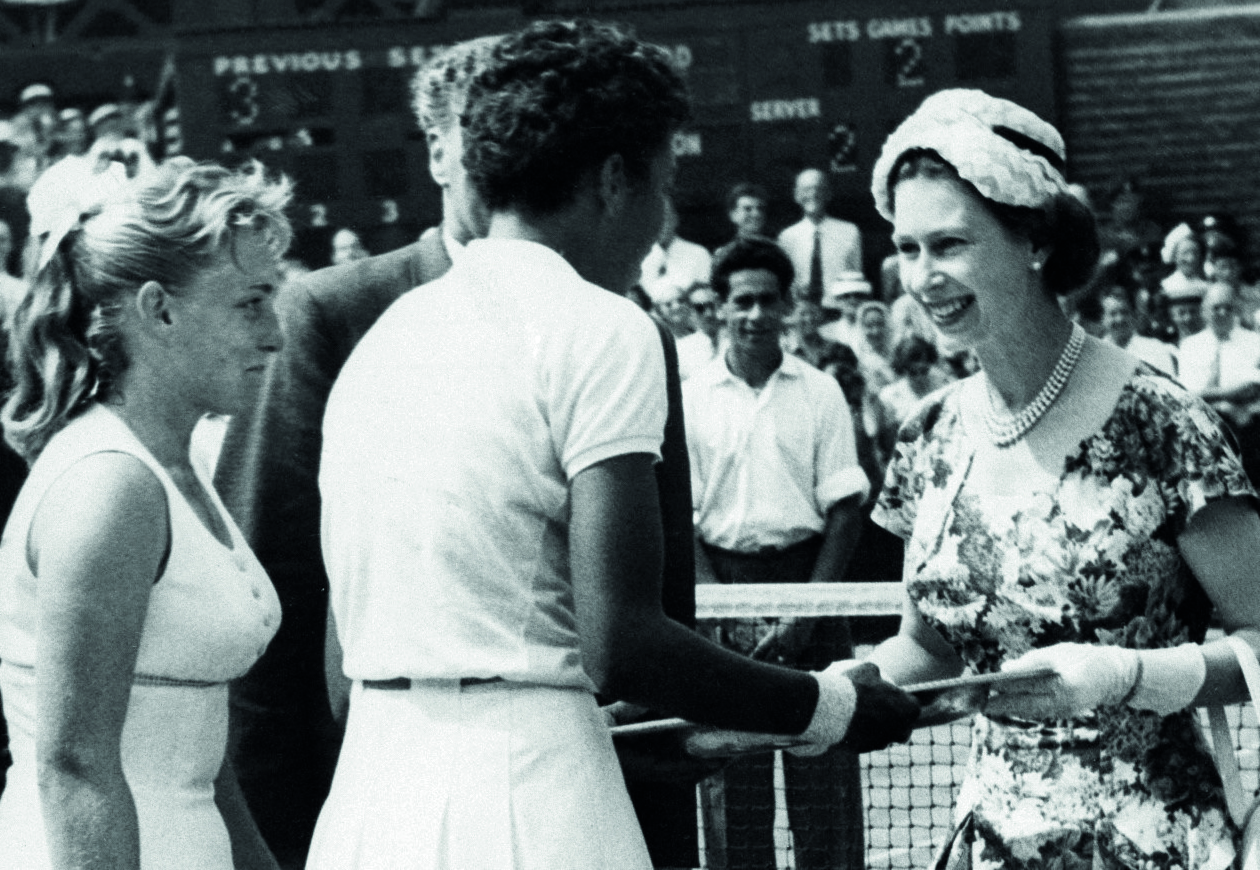

And when I - like many of you, I imagine - read Maria Bueno’s obituary this past June, I understood why the spell cast by Lolita in whites seemed so real to me. The first time my father took me to Forest Hills, in the days when the US Open was played on grass at the West Side Tennis Club, in the late 1950s, we watched the Spanish player on center court. She was a balletic player; she also was enchantingly beautiful, and she knew it. At age eleven, what was also clear to me was her impact on my seemingly Puritanical father; Dad looked as if he might pass out with pleasure just seeing her from those nice old wooden seats.

Humbert’s observations of Lolita actually playing the sport evoke not just her dexterity, but also her coyness. Most significantly, he renders a game of tennis what it is for many of us: a source of unequivocal joy, a respite from worries in life:

She would wait and relax for a bar or two of white-lined time before going into the act of serving, and often bounced the ball once or twice, or pawed the ground a little, always at ease, always rather vague about the score, always cheerful as she seldom was in the dark life she led at home. Her tennis was the highest point to which I can imagine a young creature bringing the art of make-believe. …

The exquisite clarity of all her movements had its auditory counterpart in the pure ringing sound of her every stroke. The ball when it entered her aura of control became somehow whiter, its resilience somehow richer, and the instrument of precision she used upon it seemed inordinately prehensile and deliberate at the moment of clinging contact. Her form was, indeed, an absolutely perfect imitation of absolutely top-notch tennis… My Lolita had a way of raising her bent left knee at the ample and springy start of the service cycle when there would develop and hang in the sun for a second a vital web of balance between toed foot, pristine armpit, burnished arm and far back-flung racket, as she smiled up with gleaming teeth at the small globe suspended so high in the zenith of the powerful and graceful cosmos she had created for the express purpose of falling upon it with a clean resounding crack of her golden whip.

In all that has been written about the game of tennis, from the most adroit sports journalism to players’ own accounts of tournament matches to rhapsodic encomia from the sport’s most enthusiastic aficionados, I doubt if any rivals Vladimir Nabokov’s description of Lolita’s strokes. He begins with the start of all tennis points: “ It had, that serve of hers, beauty, directness, youth, a classical purity of trajectory. ” We see its “ spanking pace ” and “ its long elegant hop. ” Nabokov gets in all the key parts of the game, including footwork. “ Her overhead volley was related to her service as the envoy is to the ballade; for she had been trained…to patter up at once to the net on her nimble, vivid, white-shot feet. There was nothing to choose between her forehand and backhand drives; they were mirror images of one another. ”

Okay, you, like me, are thinking that no backhand should really start as a mirror image of the forehand. And then you imagine yourself telling her to change her grip. Still, when Humbert says that the costly tennis pro in California had taught her a “ short half-volley ” that was “ one of the pearls ” of her game, we picture it being the perfect length, the moment of contact and angle of the racket ideal.

Humbert Humbert’s description of Lolita on the tennis court goes on for pages, becoming an elegy to everything he cherishes. At times it is comic, at other moments earnest. At her best, the teenager is, above all, a true athlete: “ She covers the one thousand and fifty-three square feet of her half of the court with wonderful ease, once she had entered into the rhythm of a rally and as long as she could direct that rhythm. ” I will leave it to you to determine if the square footage is accurate. Lolita, the novel, is, after all, like a game of tennis: a mixture of truths and flights of fancy.

Part of the appeal of tennis in novels we love is that there is something reassuring in the knowledge that the sport that obsesses many of us has also gripped some of the greatest creative geniuses of all time. In my own strange case, I also like knowing that the person whose achievement I admire in some domain I revere has the love of the game in common with me. When I was a kid, my mother more than once voiced her delight that Isaac Stern, among the greatest violists of the era, was an avid tennis player; this was especially significant since many musicians are afraid to do anything that might damage their fingers. Beyond that, as an American who lives in Paris, I am proud to show readers from Belgium and France and other Francophile countries that I somehow esteem as culturally superior to my own, that here and there the U.S. has been home to a genius or two. By geniuses I mean those writers who make tennis come alive on the page.

John Cheever has fallen out of fashion, but he was one of the greatest short story writers and novelists of the last century. Cheever played tennis well, but the way he includes it in his writing has to do not so much with the sport itself as with the way tennis figures in family dynamics. And ownership of a private tennis court becomes the mark of a way of life. Consider these two sentences at the start of Cheever’s story “ Goodbye, my Brother ”: “ When I woke the next morning, or half woke, I could hear the sound of someone rolling the tennis court. It is a fainter and a deeper sound than the iron buoy bells off the point - an unrhythmic iron charming - that belongs in my mind to the beginning of a summer day, a good portent. ” How much we have learned about a style of living in those few words! The family is rich enough to have its own clay court (while grass is also rolled, it scarcely exists on private courts in America no other surface requires a roller.) They can afford to have someone else roll it while the members of the family sleep late. They live near the sea. The person writing is attuned to the nuances of life, in particular the pleasures of a perfect summer day - one where we imagine no one hustling to work, but, rather, a day of tennis and boating.

And then it is tennis that leads us to understand family dynamics. As someone who might benefit from a few years of psychotherapy only to discuss tennis competitiveness - not of the professional sort, but among family members and friends - and the dynamics of family doubles when I was a teenager, I identify, as I imagine many of you do, with what Cheever evokes of the tension, the annoyance, the side-issues that revolve around tennis during summer holidays:

Lawrence came in, and I asked him if he wanted to play some tennis. He said no, thanks, although he thought he might play some singles with Chaddy. He was in the right here, because both he and Chaddy play better tennis that I, and he did play some singles with Chaddy after breakfast, but, later on, when the others came down to play family doubles, Lawrence disappeared. This made me cross – unreasonably so, I supposed – but we play darned interesting family doubles, and he could have played in a set for the sake of courtesy.

It is remarkable how much we learn about issues among siblings, and the character of the narrator of the story, through this interaction around the sport. Cheever’s world was one in which games loomed large, and sports were highly symbolic. In real life, John Cheever’s father disappointed him by not being more impressed with John’s skill at tennis; the older Cheever thought that the sport was not manly enough, in the way that American football is perceived to be. In his fiction, the writer did a splendid job of portraying human character through tennis — as a way that individuals can show all of our usual needs for admiration, reinforcement, and acceptance.

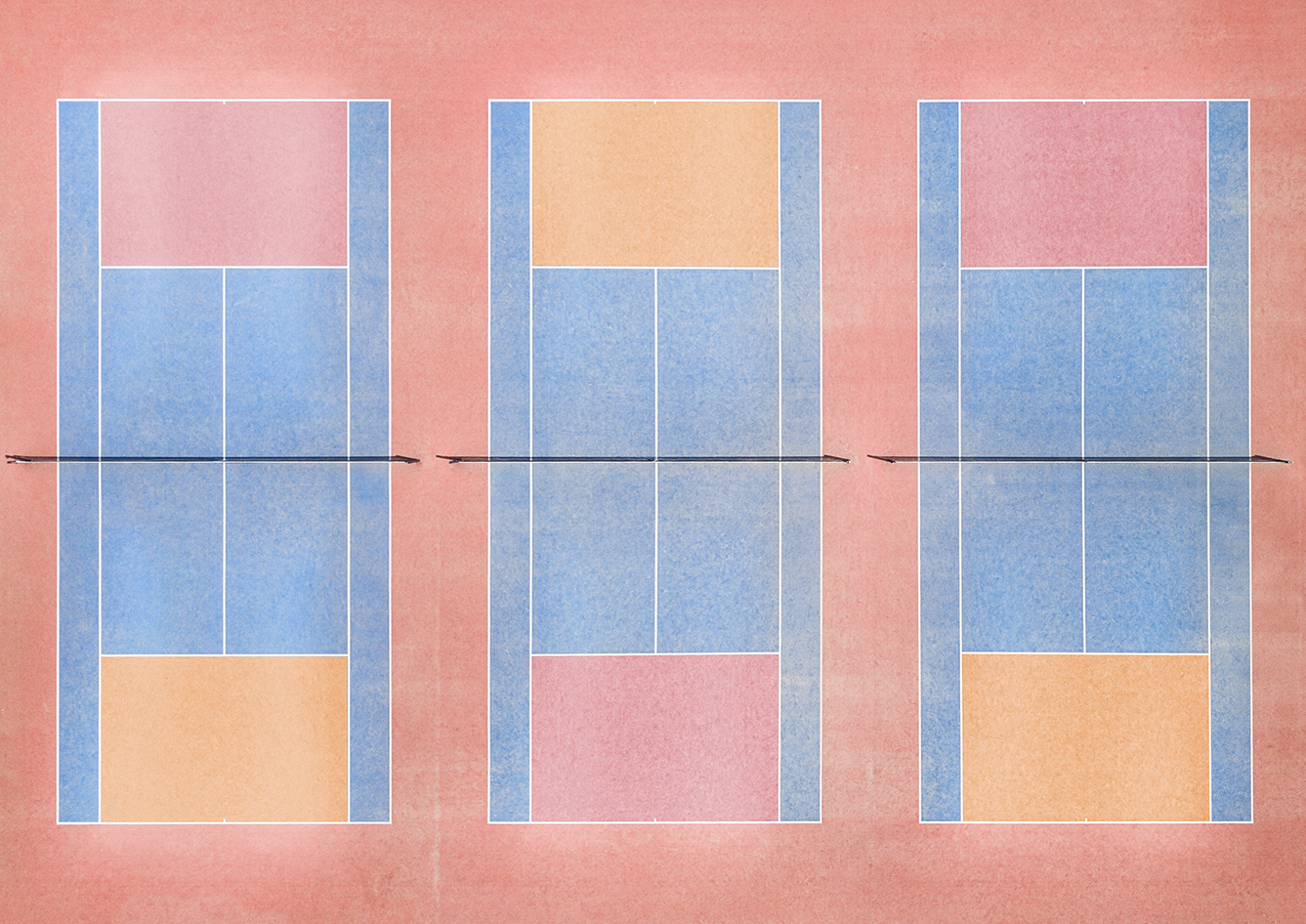

Another great American novelist named John - this time Updike rather than Cheever - writes of a world where tennis is part and parcel of an entire way of life. We feel the sport as being as central to people’s existence as eating and sleeping. In Delicate Wives, Lisa - of no last name, as if her scandalous behavior requires keeping it secret, as opposed to the situation with her rival Veronica Horst - is described as “ breathlessly fresh from a session of gossip and women’s tennis ” and is “ freckled year round ” thanks to tennis as well as golf, hiking, and skiing. It is only fitting that the moment when something seems more important than the source of her perkiness and good health that the plot thickens. “ One drizzly day in early Spring, instead of going off to her usual Sunday-morning foursome in the indoor tennis facility, she cancelled and called Les into their bedroom. ” In another Updike story, The Full Glass, the location of a town’s four tennis courts makes it the center of all the human drama. This particular balance of life is familiar to many of us; for me, Updike’s world, different though its values are from my own, makes me think of how vital to my own life the location of the nearest courts has been - whether in the park near to my childhood house, on the university campus where I spent a summer in Quito at age fifteen, or in Guangzhou when my wife and I went to China, or in Genoa when I was studying Renaissance painting there; the moment I would arrive at that familiar sight of the straight lines and right angles, always the same measures and proportions, the net straight across the middle, I felt a reassurance; wherever I am in the world, on the tennis court I am at home.

In the summers, when I worked at a marvelous institution called Tamarack Tennis Camp, in Franconia, New Hampshire, Jack Kenney, the camp director, used to service the Updikes’ red clay tennis court in the southern part of the state. He loved the merging of the game of tennis with the rest of the brilliant writer’s daily experiences, the way that John Updike and his wife Mary would joke playing singles even if their lives were fraught by the issues of other pairings

It is through the eyes of good writers that the true meaning of tennis in some of our lives becomes vivid.

Michael Mewshaw’s review of Lionel Shriver’s Double Fault in The New York Times in 1997 is entitled “ Tightly Strung. ” Those two words are perfect to describe the romance that is the focal point of the novel about a tense romance between a young women ranked Number 437 in the American Women’s Tennis Association and her Ivy League educated boyfriend who is a tennis pro ranked Number 972 in the category. Mewshaw, a sports writer who covered the men’s and women’s tours and also wrote his own novel revolving around tennis, was the perfect person to review Shriver’s gripping book. He captures the essence of the narrative as deftly as a crosscourt backhand that falls hard on target and wins the point:

I play tennis, therefore I am. She’s smart enough to know better, but Willy feels inseparable from her ranking ; her happiness depends on a number and, ultimately, she can’t love unless she’s winning. Although Eric ranks 972 when they meet, his standing rises remorselessly while hers sinks. Before long, he’s beating the top men while she, struck down by insecurity and injury, falls below 1,000 and, consequently, off the computer charts completely. The marriage similarly plunges into crisis as Willy’s court failure calls into question her very identity.

Shriver’s writing not only makes tennis the crux of the ups and downs of a love affair that becomes a marriage, but does so with searing poetry.

‘’The serve was into the sun, which at its apex the tennis ball perfectly eclipsed,’’ she writes. ‘’A corona blazed on the ball’s circumference, etching a ring on Willy’s retina that would blind-spot the rest of the point.’’

Mewshaw’s summation evokes the essence of Shriver’s accomplishment in the novel that put her at the forefront of American fiction writers: “ Shriver shows in a masterstroke why character is fate and how sport reveals it. ” [NY Times Sept 14, 1997]

When tennis appears in fiction, we have an experience that is totally different from what occurs when we read any other written account of the sport. It sharpens the portrait of at least one imaginary character; the writer uses a tennis game as a means of entering a human mind. At the same time, for those of us for whom tennis is part of who we are, any well-written reference to the sport in a short story or novel perks our interest, for we have encountered something very personal to our beings. I would be surprised that anyone reading this article would be incapable of putting down a novel or short story at the moment that a tennis match begins. On the contrary, you become riveted to every word - even if you could easily skim an account of a tennis match on the sports pages of a newspaper, or on line.

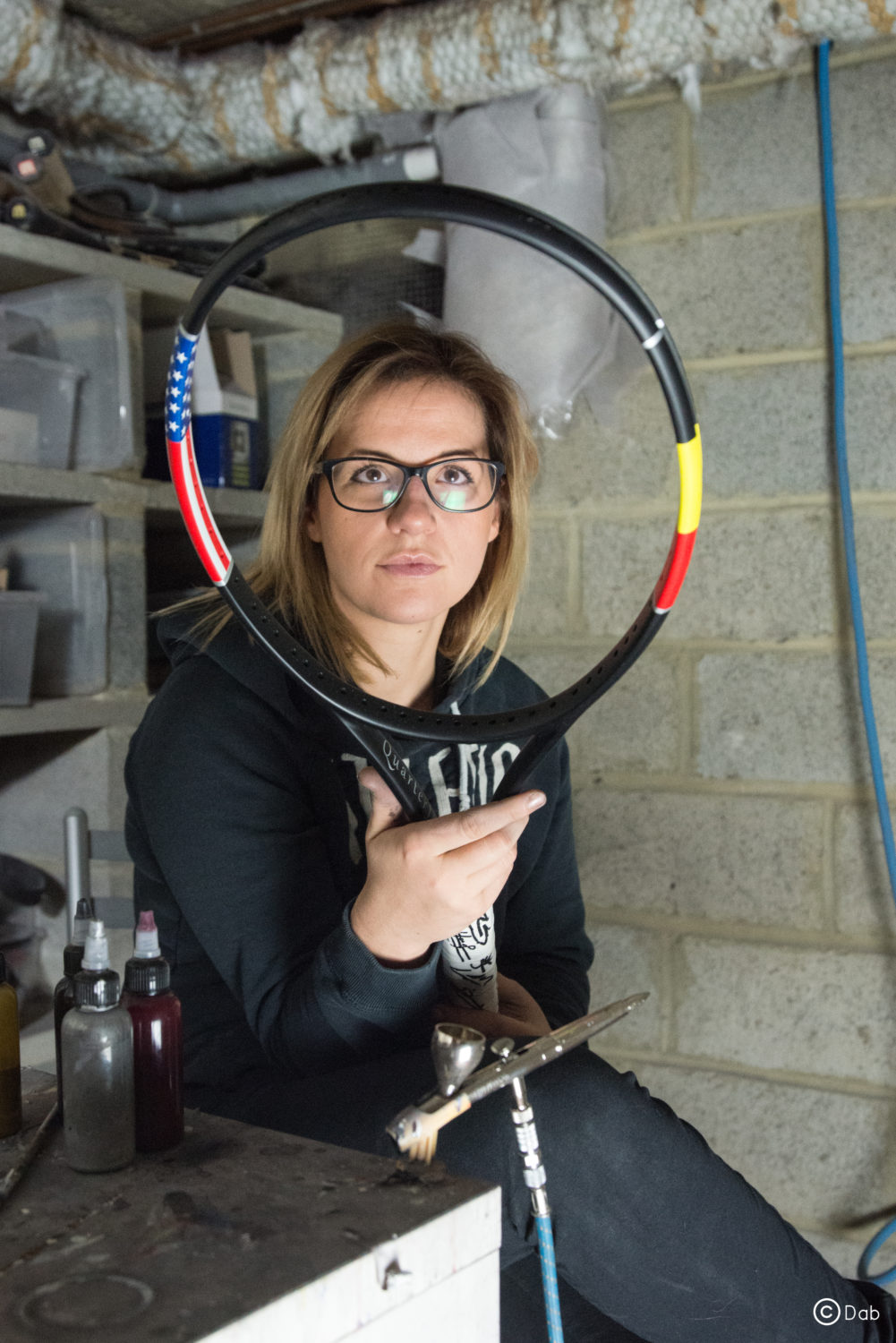

While I was thinking about this article, I stopped by my local tennis shop in Paris on the Rue du Cherche-Midi and was happy to see the premiere issue of Courts displayed prominently. I asked the owner, whom I have known for years, how he liked it. As he strung a racket to just the right degree of tautness, he said, “ Ce n’est pas du tout comme les autres magazines de sport. Ça vous amène plus loin. Vous découvrez ce que vous voulez savoir, pas les petits détails sans importance. ” When I told him I was writing about tennis in American fiction for the next issue, he said, “ Exactement! J’adorerais avoir cette perspective; c’est profond, avec ça on approche le sport d’une autre façon. ”

The characters in Don DeLillo’s Americana play baseball, basketball, and football; they box and wrestle and run. But it is when they play tennis that, in a few short paragraphs, we come to know David Bell, the book’s narrator, more intimately than at any other moment - including what you would call intimate moments. It takes a tennis game to bring him into sharp focus, both physically and mentally, for the reader. Bell is remembering a match he played when he was eighteen, and on summer holiday. For many of us, that’s the age, more than any other, when winning a tennis match is not just a sports victory; it is proof of who you are, in the eyes of others as well as in fulfillment of your own needs. We are on the edge of our seats wondering who will beat whom when Bell takes on “ Big Bob Davidson ” at the suggestion of the beguiling Jane, Bell’s older sister.

First, we get a capsule portrait of Bell’s opponent that, somehow, makes us desperate for Bell to defeat him:

Bob seemed a nice enough guy. He was tall and heavy. His face was an odd wet pink color, as if a dog had been licking it, and his blond hair was very straight.

I can’t figure out why this slightly condescending description makes us want to see Bob clobbered, but at least that is what happened to me.

And then they start to play:

My game was better than ever and I thought I’d take it easy at the outset and see what kind of pace Bob had in mind. It soon became clear that he was out to destroy me. He ranged all over the court, grim and dusty, playing in a low cloud of clay, tersely announcing the score before every serve. The harder he tried, the worse he got. His serve was erratic and he had no backhand to speak of. I was just beginning to get bored when I saw my father sitting on one of the benches that lined the courts.

How often have you had two characters come to life before your eyes in just a few sentences, and felt yourself swayed to take a side? And wondered so eagerly about what would happen next?

So now we get the father-son dynamics. Bell’s father asks him who is winning, to which the son nonchalantly replies that he “ took the first set ” but is not even sure of the score - although it was probably six-one. “ I’m not very involved in this particular match, ” Bell explains.

His father is desperate about the match, though. “ Well, get involved … I want you to whip his ass. ”

His father does not even know Bob Davidson, but feels that the giant fellow has invaded his house, and might be pursuing Jane. Bob “ might be the sweetest guy in the world, ” but the father is threatened by him. “ Go get him. Go run his ass ragged, ” he instructs his eighteen-year-old son.

Bell’s subsequent victory inspires a pride and camaraderie familiar to many of us for whom sports, and competitiveness, are interwoven with our relationship with at least one of our parents:

I beat him in straight sets, easily, embarrassing him, taunting him with soft raindrop shots which sent him from one end of the net to the other, then drilling a hammer past his ear. When it was over my father clapped me on the back, rubbed my neck, congratulated me on what he called a truly historic blitz, a glorious rout. All at the expense of the interloper, it was one of those strange bursts of bloodlove which are both puzzling and overpowering in their dimensions of joy.

It takes a scene of what is allegedly fiction to make us feel that intense drama most of us would be afraid to admit in a recitation of facts.

David Foster Wallace is the writer whose name comes up most frequently when one discusses writers and tennis; String Theory, his book devoted to the sport, remains a great favorite. He was, in fact, tennis-obsessed. The sport permeates his fiction as well as his non-fiction, and could describe exchanges across the net with unequaled vivacity.

Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest is set in part at the fictional “ Enfield Tennis Academy. ” An account of players called Hal and Stice battling on the court is a small example of the panache with which Wallace describes the sport; if ever words could have you seeing every muscle flex and hear the ball bounce, it is these:

Hal’s first serve hadn’t Stice’s pace, but it had depth, plus a topspin Hal achieved with an arched back and faint brushing action over the back of the ball that made the serve curve visibly in the air, egg-shaped with spin, to land deep in the box and hop up high, so that Stice couldn’t do more than send back a deep backhand chip from shoulder-height, and then come in behind a return that’s been robbed of all pace. Stice moved to the baseline’s center as the chip floated back to Hal. Hal’s pivot moved him to the right so that he could take it on the forehand, another looper dripping with top, right back in the same corner he’d served to, so that Stice had to stop and sprint back back the same way he’d come. Stice drove the backhand hard down the line to Hal’s forehand, a blazing thing that made the audience inhale…

We inhale as well, with sheer excitement, and the point still has not ended.

Fiction? This is tennis itself: exhilarating, diverting, glorious.

Story published in Courts n° 2, summer 2018.