From Rags To Bags

Life works in mysterious ways. Have you ever heard a more overdone cliché? And yet, it’s true. It’s never straightforward, never the way we imagine it would be. A girl smiles at you on the train, and a moment later you imagine yourself 20 years down the line with two grown up kids. You spend the next few months taking the same train, hoping to catch a glimpse of her. Fast forward those 20 years, however, and you’re in a happy marriage with a train conductor. You met on Platform 3.

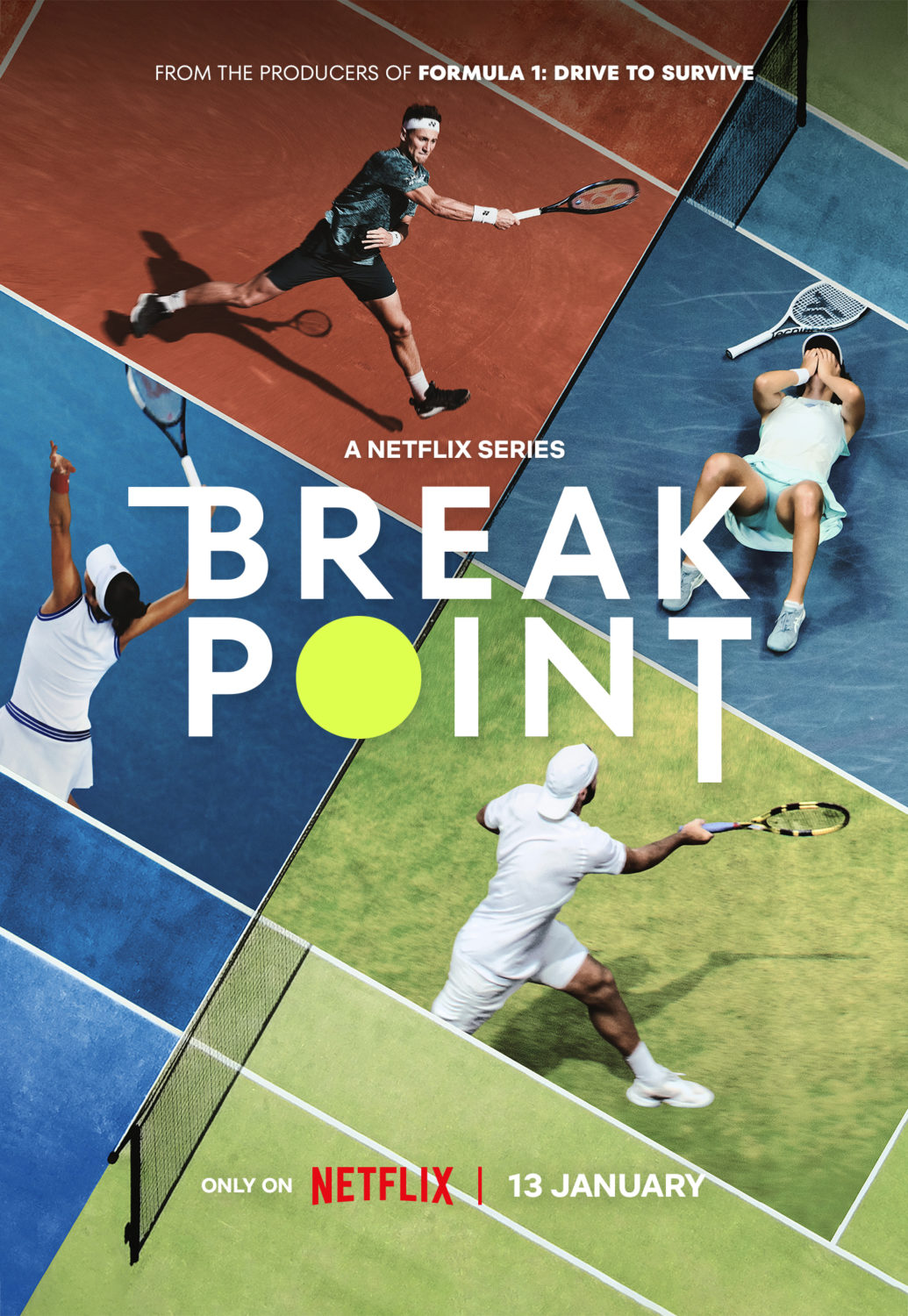

When Jack Oswald swung his first child-sized tennis racquet, he began fostering dreams of becoming a professional tennis player. And while he embarked on a journey that, in another life, could have led to him squaring up against Stefanos Tsitsipas on Philippe Chatrier, what he couldn’t at the time imagine was that—fast forward 20 years—he would find himself stitching tennis bags at three o’clock in the morning. And he had never been happier.

Born to British parents, Oswald grew up in the US. A large chunk of his childhood was spent on tennis courts, honing his skills with the racquet. “I have always been a hard worker, and wanted to try and get as good as I possibly could,” Oswald tells me over the phone. “I really love the idea of getting that one percent better and better every day, and trying to see where it could take me.” As his tennis abilities grew, Oswald’s dreams started to take on a shape of reality. When he was 13, he made the difficult decision to leave his parents behind and embark on a journey to Europe, all in pursuit of his tennis dream. The choice represented a significant sacrifice at a young age, one that would go on to shape the young player’s unwavering commitment and dedication to his tennis career. Over the following six years, he spent his teenage years living in France, Spain and the UK, with limited opportunities to see his family. At the age of 17, Oswald felt confident enough to try his luck on the professional Tour. It was a tough life, and by Oswald’s own admission, he was never an exceptional player. “I only really made it to the lower levels of the professional tennis circuit,” he says. “I was playing on the Futures circuit mainly—10k, 15k, then eventually 25k events—but those were really the maximum I got to.”

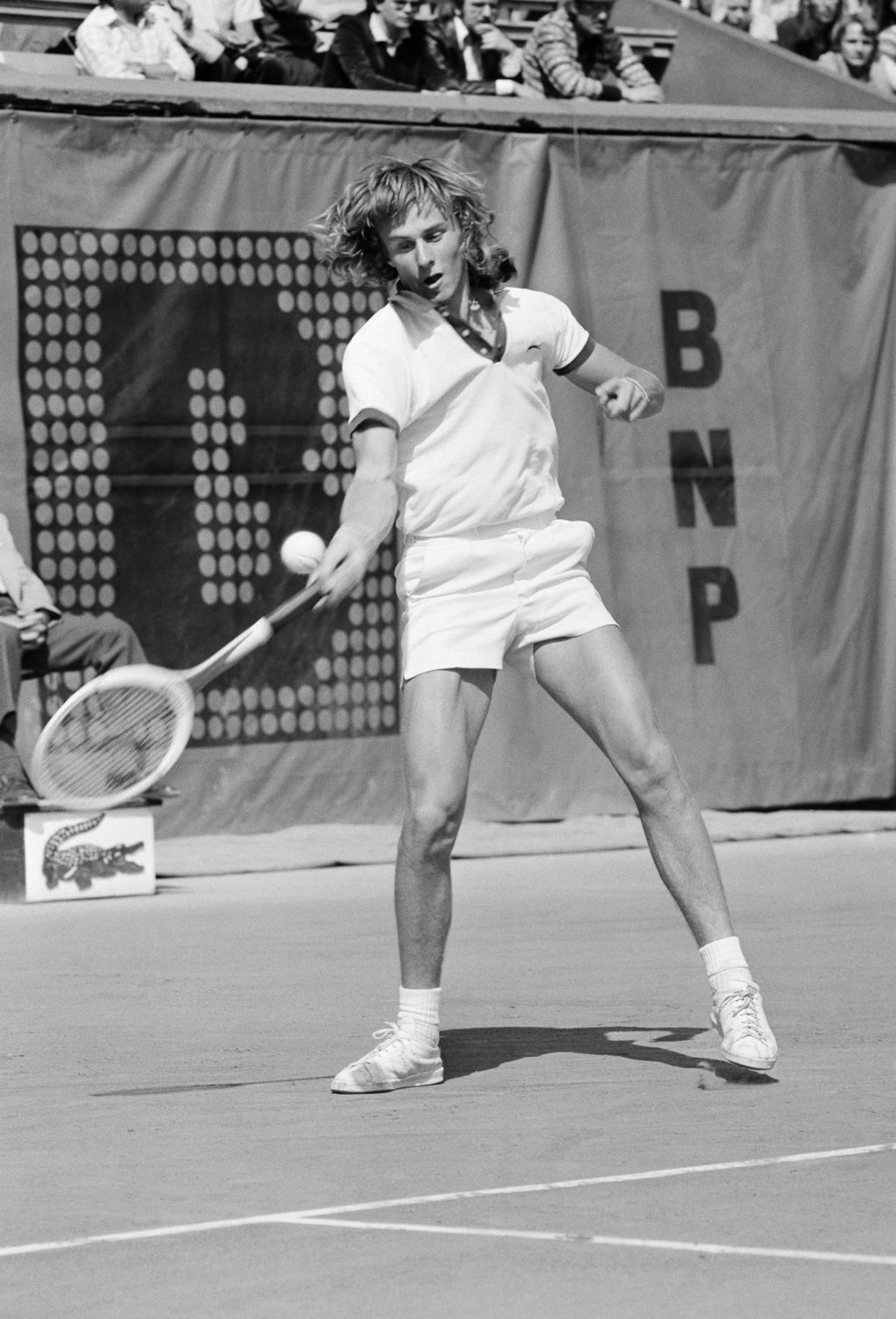

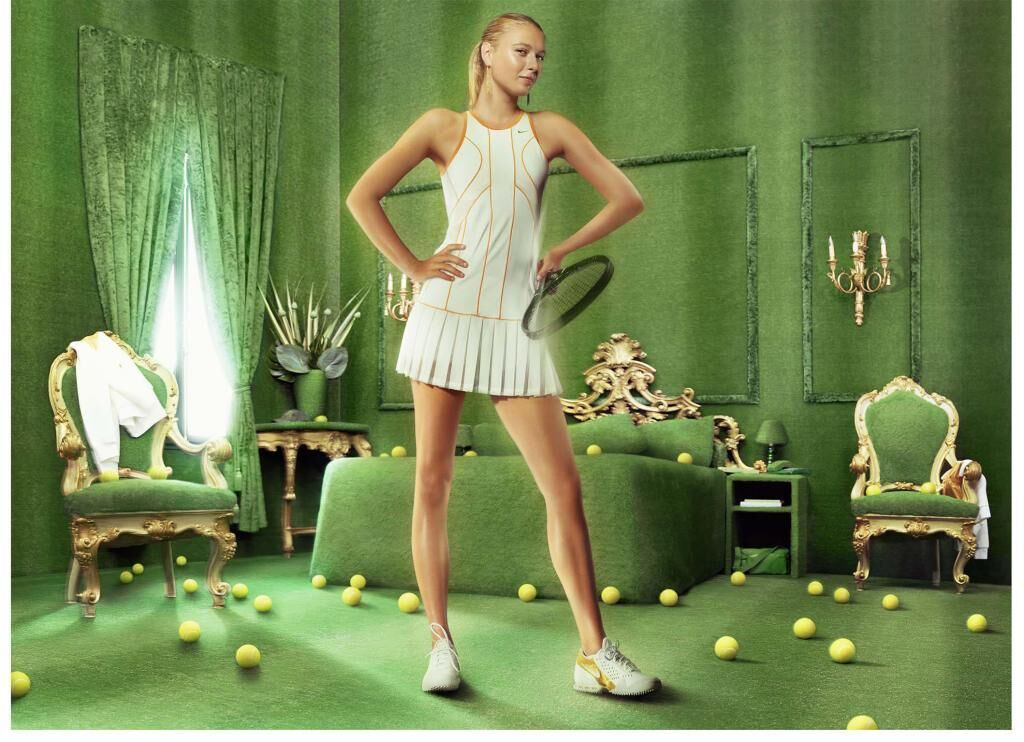

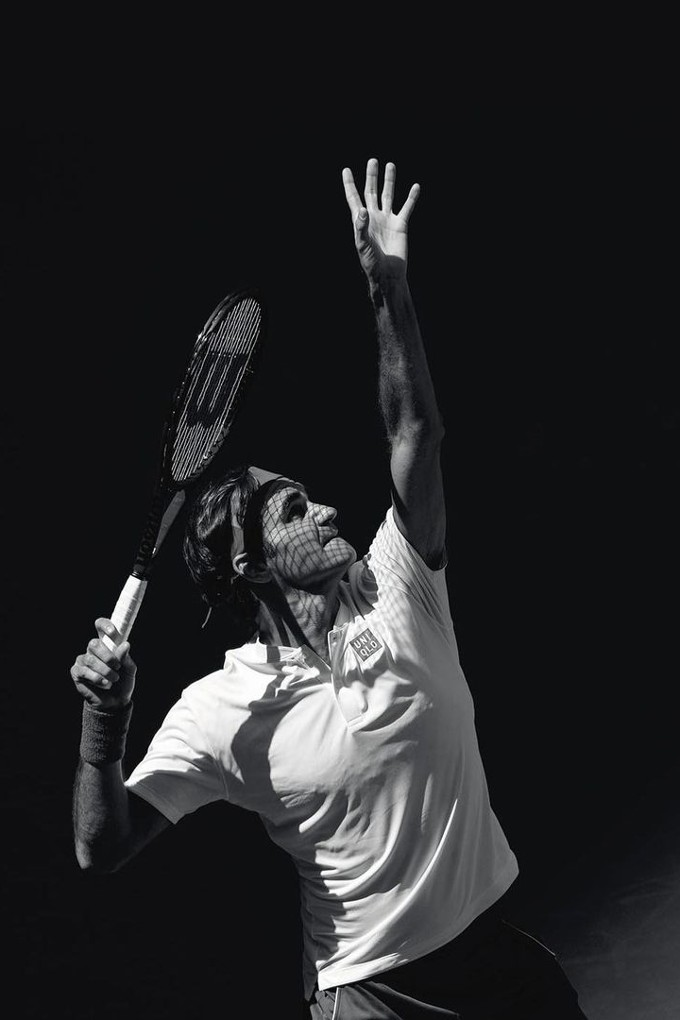

Playing with a one-handed backhand, Oswald always admired the aesthetic aspects of the game—the hidden beauty of a perfectly executed stroke. “I loved watching Gasquet,” he tells me. “And on the women’s side, Justine Henin. I’m a fairly small tennis player and not like Del Potros of this world, and the way that she was able to take on players, who were much bigger and taller than her, with so much more firepower, really inspired me.” Eventually, the financial and logistical demands of the sport took their toll on Oswald, and he decided to hang up his racquet. Despite the difficulties, he loved the experience. “I was just enamoured with everything,” he says. “I tried to play all the satellite tournaments, spending my time in Europe, Africa, Asia, and back in the US again. I had the most amazing time.”

While Oswald did not get to reap a great deal of the benefits afforded by the tennis life at the highest level, he did experience many of its downsides. For a while, travel was a constant in his life, and with it, packing. Criss-crossing the world on a weekly basis in search of results, he developed an intimate relationship with his luggage. “I was travelling a lot on the Tour. With a lot of luggage and bags—on flights, on trains, on buses, in hotels, across cities,” he lists. “And I became very aware of all the difficulties that travelling athletes encounter.”

Out of the frustration was born an idea. During downtime between matches, he began toying with the possibility of creating his own luggage. “It started back in 2018,” Oswald says. “I was just trying to design better tennis and travel bags for myself, and it became a sort of side project. I was becoming so interested in the innovation side of things, and in textiles, trying to come up with a way that would make it easier for athletes to travel with their tennis gear.” The switch from a tennis player to a tennis bag designer was dramatic. But Oswald threw himself into the world of sports equipment carriers with the same zeal that set him off on his journey to becoming a budding tennis professional. “I knew absolutely nothing about product design,” he admits. “I knew nothing about business but I took to it with the same ethos as with my tennis. I just worked on getting that one percent better at it each day.”

By then, his interest in tennis bags becoming a full-blown passion, the budding entrepreneur was introduced to a soft goods designer—a person who, as Oswald puts it, “made sure I didn’t stitch my fingers together.” What followed was countless hours spent in a workshop—stitching, laser cutting, bonding fabrics, sanding down—a sharp turn from the kind of precision required on a tennis court. “It was a lot of trial and error,” Oswald remembers. “We probably went through well over 50-100 prototypes to get to where we were with the first version of our bags that we started to sell.” Just as on the tennis court, he was looking for the perfect blend of functionality and beauty, and with a lot of dedication, hard work, “learning on the job and a huge amount of mistakes,” the project blossomed into Cancha. “The name came to me while I was playing a Futures event in Peru,” Oswald explains. “It means court in Spanish, but, also, ‘to have a cancha’, means someone who is a go-getter. It became the essence of our brand.”

Oswald went on to obtain an MBA to help him with the business side of his project, as well as meeting scores of different industry professionals to learn all there was about textile manufacturing and design. “I find it interesting how aligned my tennis days are to life in business. There are so many similarities in terms of the mentality and the mindset that any tennis player and any entrepreneur must have,” he says. “It’s the patience, and the long term vision but still [being] focused on the short steps towards that vision.” Looking back with the benefit of time, Oswald admits the overwhelming scale of the task. “I wasn’t prepared for it,” he says. “I don’t think anyone is at the beginning. But it’s all about the way you approach it.”

Today, Cancha is a fully-formed business. A look on the brand’s website reveals products for tennis, padel, pickleball as well as day to day bags in different colours. All Cancha bags are customisable—the modular aspect being one of the main selling points. “At the end of the day, everyone’s travel needs are different,” Oswald says. “They carry different things, they have different daily routines and needs. So for us, a one-size-fits-all bag didn’t make sense.”

I lightheartedly ask him to convince me to switch from my old Babolat bag to a Cancha one. I expect an aggressive sales pitch but what comes is a matter-of-fact statement. “There is nothing wrong with your bag,” Oswald replies. “But if you want a durable one that will fit all your gear, keep it dry, and can accommodate other day-to-day accessories such as your laptop, you will like a Cancha bag.”

Oswald’s passion is as evident as it is infectious. He talks about different designs of his bags with the kind of affection people afford their pets. This one is for a casual player. And this one has a larger capacity, holding up to six racquets. This one has an attachment for your wet clothes. And this is a mini version for padel or even pickleball. Surprisingly, the man behind Cancha is still not pitching. He doesn’t try to convince me that Cancha is more than a product—he believes in it. “We work with non-profit organisations as well as the tennis sector,” he says. “We’re trying to get behind the sport in terms of the idea of travelling for tennis, and seeing new places, exploring new cultures, and sharing experiences over a shared passion, which is tennis. “And this is what our brand has been built on over the last couple of years.”

Cancha aims are high, and the aspirations go beyond being just another tennis accessory company. “We’re members of ‘1% for the planet’ so we donate one percent of our annual revenue to environmental non-profit organisations. Our fabric is Bluesign certified, too. It’s all sustainable,” Oswald says.

From the start, Oswald’s idea was to listen. He is open to feedback, both good and bad, through email, Instagram posts or in-person interactions. “We are going to have a presence in the Wimbledon Village with the team during the Championships, and we will be speaking to customers,” he says. “You can’t please everyone, but over the years, we’ve had some amazing customer reviews. And I think that is because we hear the customers. We approach every day with the mindset of trying to make our bags that little bit better every time.”

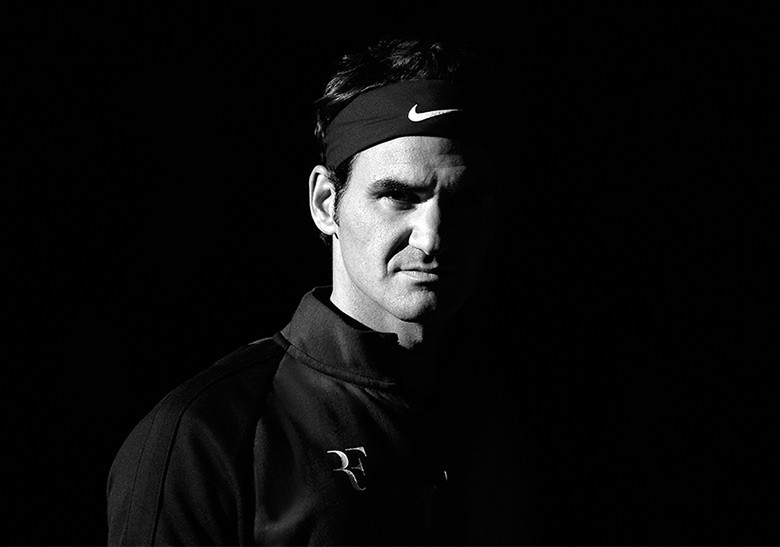

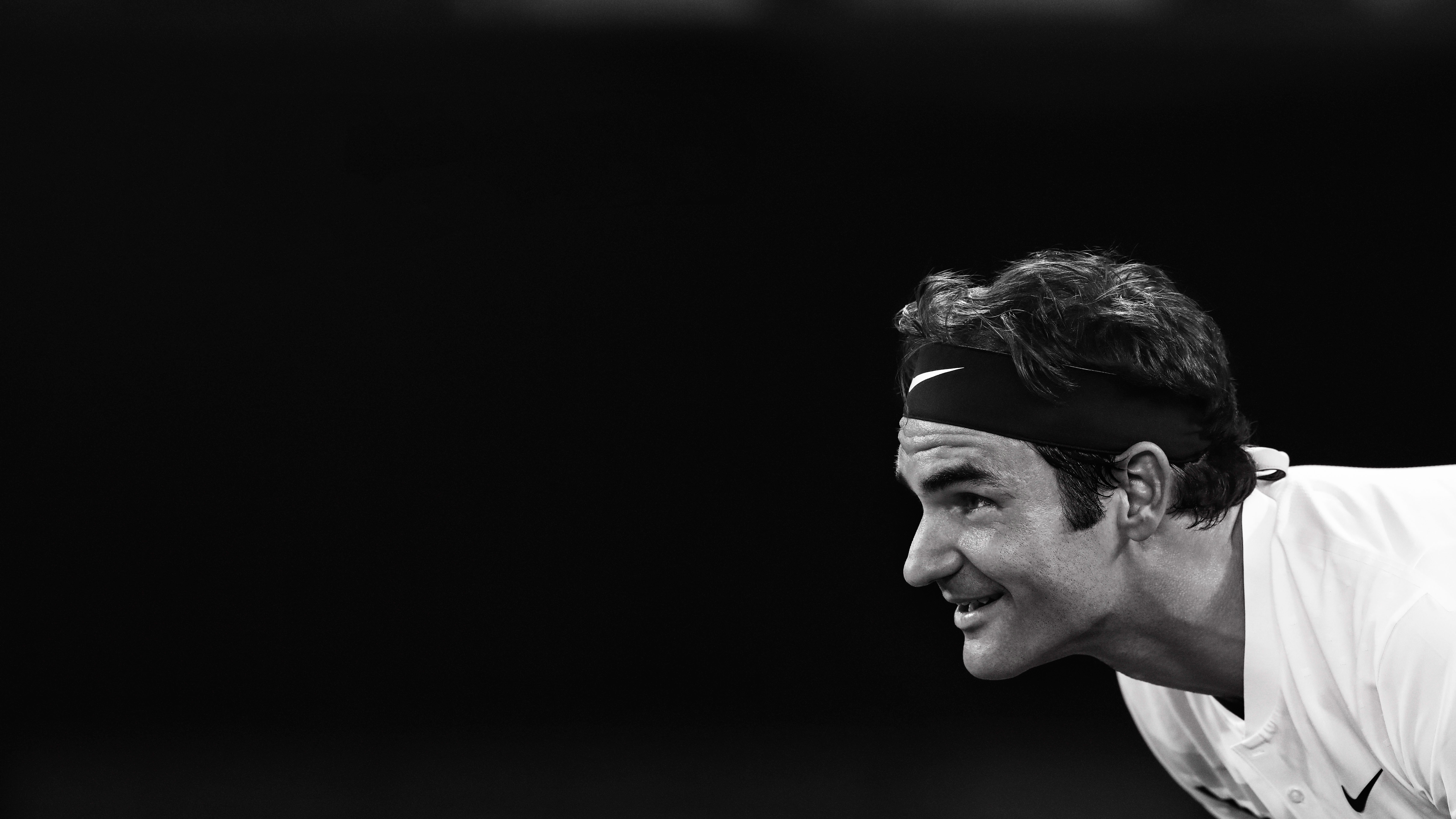

I ask Oswald about his goals for Cancha. I float the idea of the perfect tennis bag—one to displace all bags. In response, he again draws parallels between his business venture and his playing days. “Tennis is one of those sports where you are just entirely responsible for yourself and your own success, but also your own happiness as a tennis player. It’s all about your mindset,” Oswald says. “Perfection has to be the aim. But it doesn’t mean that you’ll ever get there. Even if you’re Roger Federer,” he adds. “But it’s that kind of mindset that will get you 90% of the results.”

Story published in Courts no. 4, Summer 2023.