Roger Federer and the Modern Crisis of Masculinity

My earliest memory of crying—sad tears, not just a reaction to a stubbed toe or twisted ankle—is July 6th, 2008. It starts like many of my painful memories: a netted Roger Federer forehand.

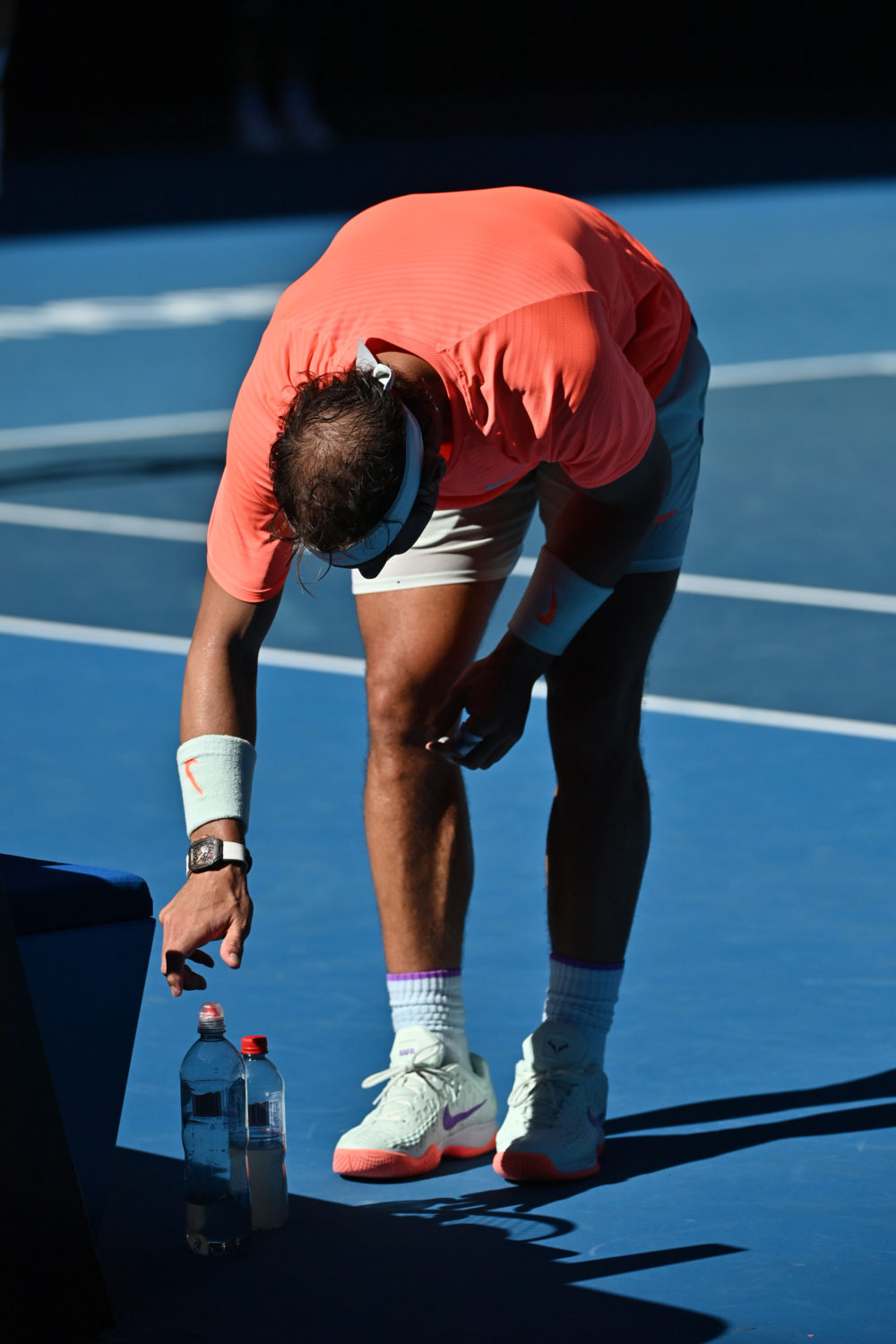

Federer’s opponent that day, the young, capri-donned Rafael Nadal, walked towards the baseline of Wimbledon’s Centre Court at 9:16 PM London time. From my couch in Oregon, I inhaled sharply, then caught my breath. Eight time zones away, I couldn’t risk derailing Federer’s focus.

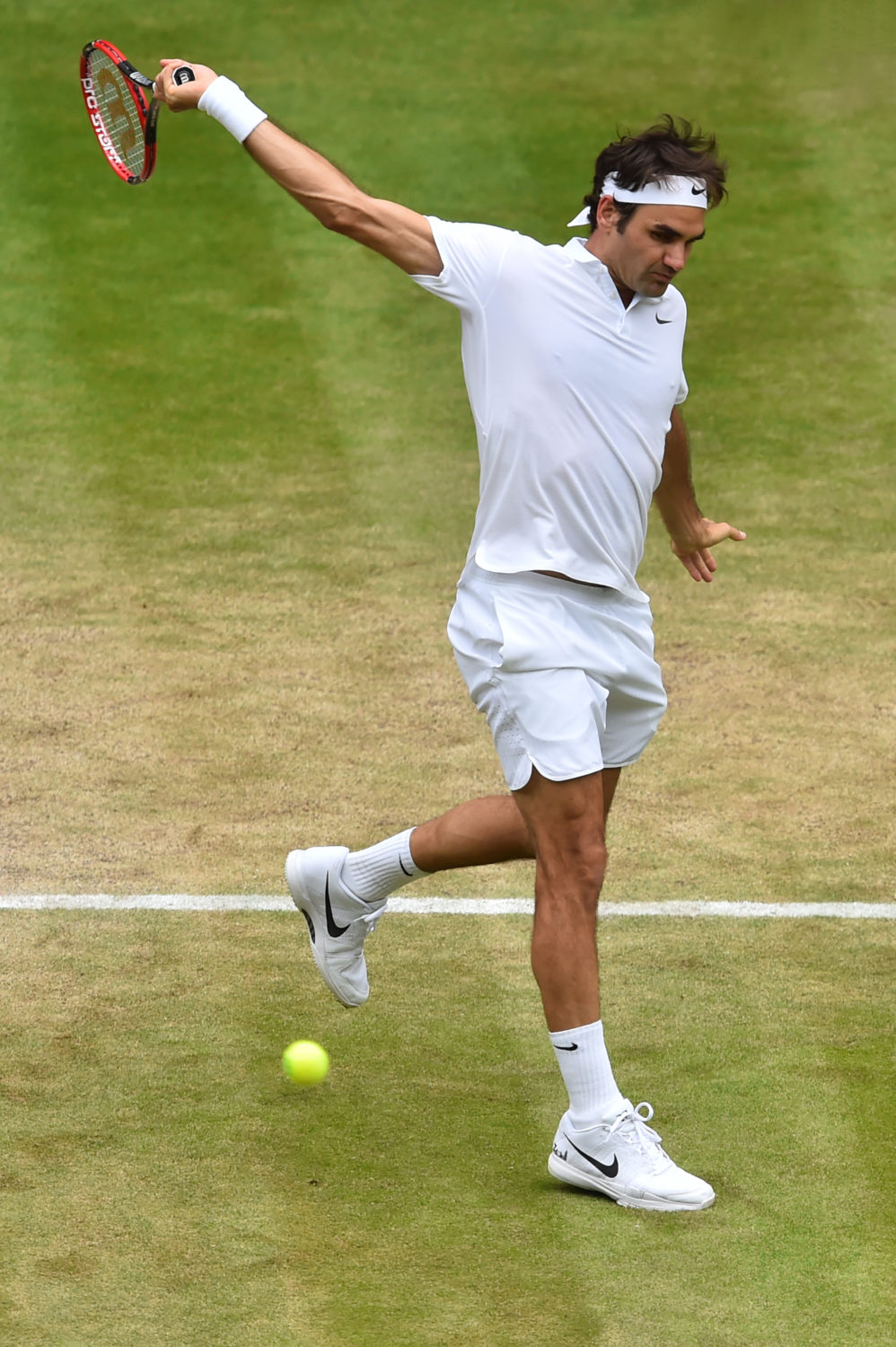

Nadal wiped the sweat from his face, bounced the ball six times, and tossed it into the fading Centre Court light. Federer blocked the serve with his forehand, sending a looped return up the line to Nadal’s backhand. Nadal’s response landed short to Federer’s forehand, like an errant chess move inviting checkmate. I let my eyes drift up the screen, anticipating a crisp winner. But Federer’s forehand caught the net. The ball fell to the grass, Nadal collapsed in victory, and my nine-year-old heart broke for the first time.

I watched the entire seven-hour Wimbledon spectacle that day: two rain delays, five sets, and countless flicked passing shots. After hanging on every point, every locked rally, and every bathroom break, I surrendered to a wave of uncontrollable emotion. I laid down on my bed and cried.

My tears quickly triggered another emotion. Shame. I had just crumpled beneath an unspoken burden of my young manhood. The men around me never cried—what was I doing? I wiped the tears away and returned to the living room, just in time to see a cardigan-donned Federer lift his runner-up trophy to a crowd of cheers and camera flashes.

Slowly, my heart recovered from the Wimbledon final. I tried to be productive in my mourning, using the heartbreak as on-court fuel to train harder. Federer, like always, provided the underlying blueprint for my practice sessions and tournament matches. “Federer practicing in Hamburg 2008 – ground strokes” blanketed my YouTube watch history. I spent hours with a ball machine emulating half-volley drop shots. I even briefly transitioned to a doomed—albeit not from a lack of devotion—one-handed backhand. Grand Slam seasons wore on, and soon the 2008 Wimbledon loss marked nothing but a brief scene in the video montage of Federer’s career. I kept playing tennis, graduated college, and still never really cried.

Last September, I turned on the Laver Cup to witness Federer’s final match: doubles alongside Nadal, his closest rival throughout a 24-year career, and the man who beat him at Wimbledon 14 years earlier. Reporters billed it as a lighthearted send-off. Federer, coming off a series of right knee surgeries, wasn’t fit for anything beyond the Laver Cup’s two-out-of-three set, third-set tiebreaker format.

The match itself ultimately induced more anxiety than closure. Nadal’s grueling run at the US Open erased any hope of compensating for Federer’s knee. Neither man’s legacy hung in the balance. After a 2-hour, 12-minute struggle, time edged out the Swiss-Spanish partnership just as much as their Team World opponents, Jack Sock and Frances Tiafoe. I straightened up and grabbed the remote as the teams shook hands, bracing myself for Federer’s last moments on court. I never expected the most vivid scene of the event, and to me, Federer’s career, to quietly occur off-stage on Team Europe’s changeover bench.

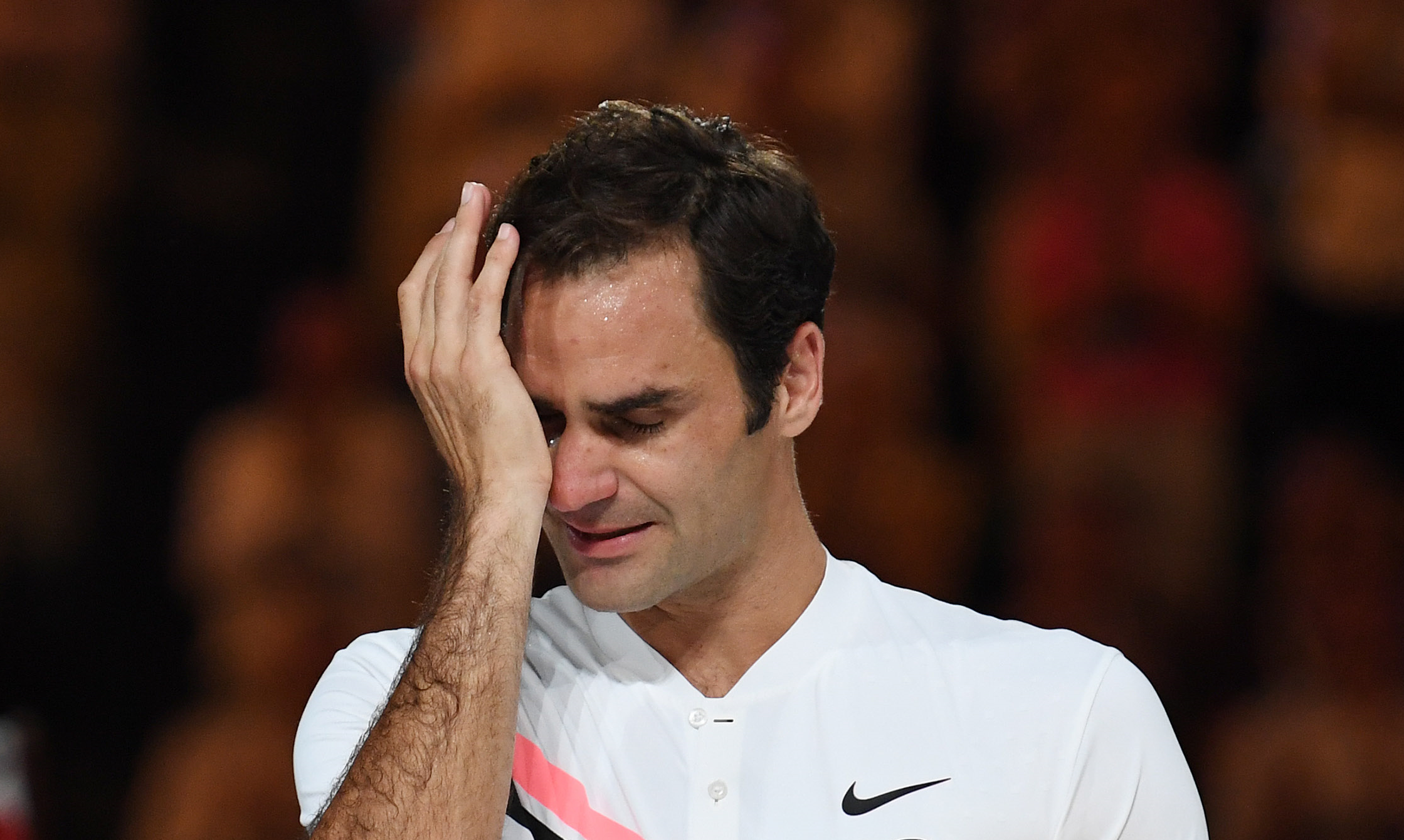

Waiting to give his post-match interview, Federer broke down sobbing. At first softly, and then almost uncontrollably. Nadal started crying alongside him. The two men, epochal rivals of their sport, and by all societal standards, icons of athleticism and masculinity, sat holding hands as decades of emotion washed over them. They embraced the moment together, sobbing on the bench as Elle Goulding sang Still Falling for You to clips of Federer’s greatest wins. It was an unscripted moment of vulnerability, physical affection, and positive male friendship—rare in popular culture, and virtually unthinkable in professional sports. As a young man in today’s society, it was everything.

Men don’t cry. I internalized that unspoken maxim, even at nine. And despite my personal growth—therapy, close male friendships, and positive role models—I was shocked to see Federer’s public display of vulnerability. The subconscious parameters of my masculinity still flashed red. Healthy male friendships rarely reach mainstream celebration. Physical touch or affection between two straight men? Even less so—unless it’s a punchline or homophobic trope.

Federer’s retirement tugged at the desperate need for positive masculinity in today’s society. Men, especially young men, face a barrage of toxic masculinity at work, in school, and most recently, online. I struggle to name a male TV character from my childhood, even one, whose strength—and often, implied worth—rested in emotional intelligence or sensitivity. The boundaries of traditional masculinity prohibit displays like Federer and Nadal’s embrace. But misogyny, emotional detachment, and physical violence? Just open Tiktok and wait. Today’s algorithms privilege the Andrew Tates over the Roger Federers.

Unfortunately, sports perpetuate this masculinity crisis. I played tennis competitively for almost 10 years growing up, and never questioned why throwing my racquet or screaming obscenities was tolerated over crying. If you cried, you were invariably a “pussy.” On-court outbursts, smashed racquets, even self-inflicted violence rarely elicited more than an eye roll. In a sport so characterized by emotion, full of highs and lows, loneliness and elation, suffering and solace, why do we accept so few displays of masculinity?

Here, the professional circuit bears a responsibility; the starkness of Federer’s vulnerability also serves as a grim reminder of the state of masculinity on the ATP Tour. Rage is an implicitly accepted language, spoken through on-court outbursts that often precede physical violence. Nick Kyrgios, the popular No. 21-ranked Australian, violently broke two racquets at the 2022 US Open after losing to Russia’s Karen Khachanov. The Guardian, writing about the incident, described Kyrgios as “fiery”. Not unprofessional or violent—just fiery. Two rounds early against Benjamin Bonzi, he attacked his player’s box from the court, shouting, “Go home if you’re not going to fucking support me.” His “firey” brand of masculinity works. Kyrgios is now the star of Netflix’s new tennis docu-series, Break Point. Violence, rage, and past abuse allegations (assault charge against Nick Kyrgios was dismissed February 3, 2023, after he pleaded guilty to pushing ex-girlfriend Chiara Passari) notwithstanding, he remains one of the most popular figures in professional tennis.

Commentators, often women, have voiced concern about such on-court violence. After Jenson Brooksby threw his racket at last year’s Miami Open, inadvertently crashing into the feet of a nearby ball boy, former players like Caroline Wozniacki and American legend John McEnroe called for more accountability. Similar voices criticized Alexander Zverev’s violent battering of the umpire’s chair at last year’s Mexican Open.

But why do we only speak up when on-court violence inadvertently impacts a fan or court attendant? The silence endorsement, even media romanticization, of smashing racquets, cursing umpires, and screaming at fans is a signal to young boys watching at home: as long as your violence is self-inflicted, it remains an acceptable way to express yourself—on and off-court.

Masculinity is in crisis. Boys today desperately need examples of manhood removed from traditional archetypes of violence, aggression, and social domination. We need role models who show can strength in vulnerability, men who understand the importance of physical affection and deep, emotional friendship. We need men like Roger Federer.