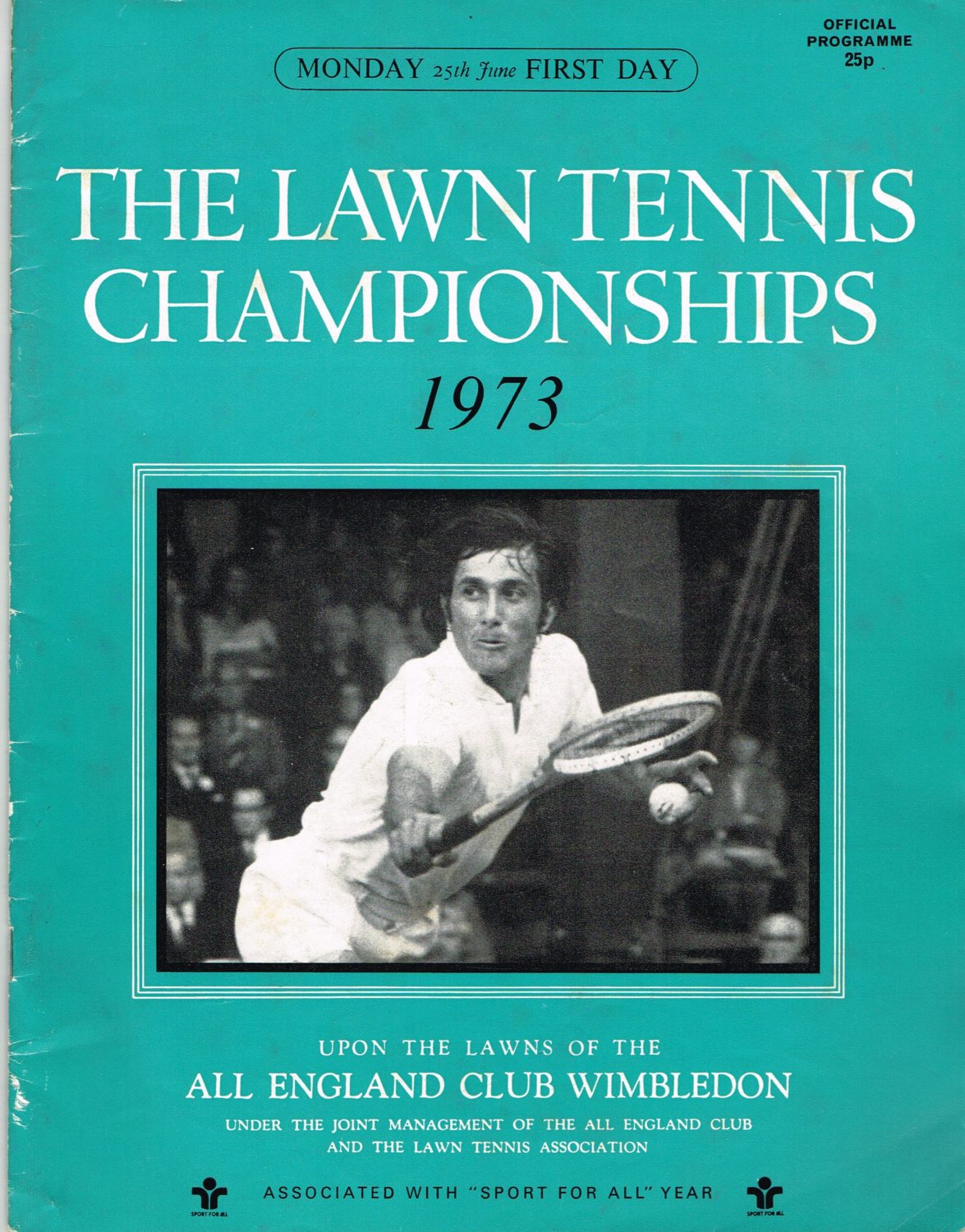

50 Years on—Wimbledon, 1973

Wimbledon 1973 was a huge success despite numerous interruptions for rain and the absence of seventy-three of the world’s best men players. Seventeen year old Bjorn Borg burst into the spotlight and another teenager, eighteen year old Chris Evert, beat top seed Margaret Court to reach the Ladies’ Singles final. Roger Taylor was just four points away from becoming the first male British finalist in the post-war era. But the overwhelming feature of the fortnight was the Wimbledon crowd, which turned up in huge numbers every day to finally top the 300,000 mark, the second highest figure in Wimbledon’s history, despite the absence of most of the world’s leading men.

The two weeks leading up to the tournament were overshadowed by what became known as the ‘Pilic Affair’. Nikki Pilic, of Yugoslavia, an accomplished player though not quite of the highest class, was, at 33, at the stage of his career where he needed to earn money in the brave new world of open tennis while he still could. According to the Yugoslav Tennis Association, he had committed to play for his country in a Davis Cup tie against New Zealand, but then reversed his decision and went instead to Las Vegas to play in a $60,000 event. Pilic was suspended from all tennis for a year, which was reduced to one month on appeal to the International Lawn Tennis Association. Pilic had just reached the final of the French Open, losing in straight sets to Ilie Nastase, but that tournament had commenced in May, before his one month suspension had started. His ban started on 1st June, meaning he would miss Wimbledon.

This quickly escalated into a dispute which pitted the newly-formed Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), led by Chairman Jack Kramer, against the tennis establishment, and at the heart of that was Wimbledon, which was just a few weeks away. The timing of the dispute was awkward or ideal, depending on your point of view.

The affair rumbled on for two weeks before the tournament, and was front page news. The ATP’s members backed Pilic, declining his offer to withdraw from Wimbledon for the sake of peace. There was a far bigger principle at stake, the players’ right to choose when and where they played. History now shows that Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and other top stars have benefited enormously from the players strike led by Kramer, Arthur Ashe and Cliff Drysdale back in 1973.

The ATP, founded less than a year earlier, counted the world’s best players amongst its ninety- seven members. On Friday 15th June the ATP took Pilic’s appeal against the ban to the High Court, arguing “restraint of trade”. The case ran until the following Tuesday, 19th June, with the ILTF’s one-month ban being upheld. Mr. Justice Forbes, presiding, said: “The curious thing is that in all the evidence I have heard there is no reason put forward for him not playing in the Davis Cup match.” Costs estimated at £5,000 were awarded against Mr. Pilic.

The draw, scheduled to take place on Wednesday 20th June, was delayed by two days in the hope of a last-minute resolution to the dispute, but none was forthcoming. After a meeting between the two sides, Herman David, Chairman of the All England Club, commented: “We reach a state of impasse. It is not a situation we like and really has nothing to do with Wimbledon.”

Stan Smith, who would have been the defending champion, felt sorry for the British fans. “We don’t have anything against them, or British Tennis,” he commented ruefully.

The deadline for players wishing to withdraw from the tournament was Saturday 23rd June, and when the crunch came 73 of the ATP’s 97 members backed up their words with action. A new list of seeds was drawn up, with just three of the original sixteen named players remaining in the tournament. Seeded first in the original list was John Newcombe, the defending champion from 1971 who had missed Wimbledon in 1972 as he was contracted to play in the World Championship of Tennis, whose members were banned from ILTF events. He was replaced by a somewhat reluctant Ilie Nastase, the world’s No 1 player who had been instructed to play at Wimbledon by his national association. He was joined by Britain’s Roger Taylor, who resigned from the ATP as he felt compelled to support his home Grand Slam tournament.

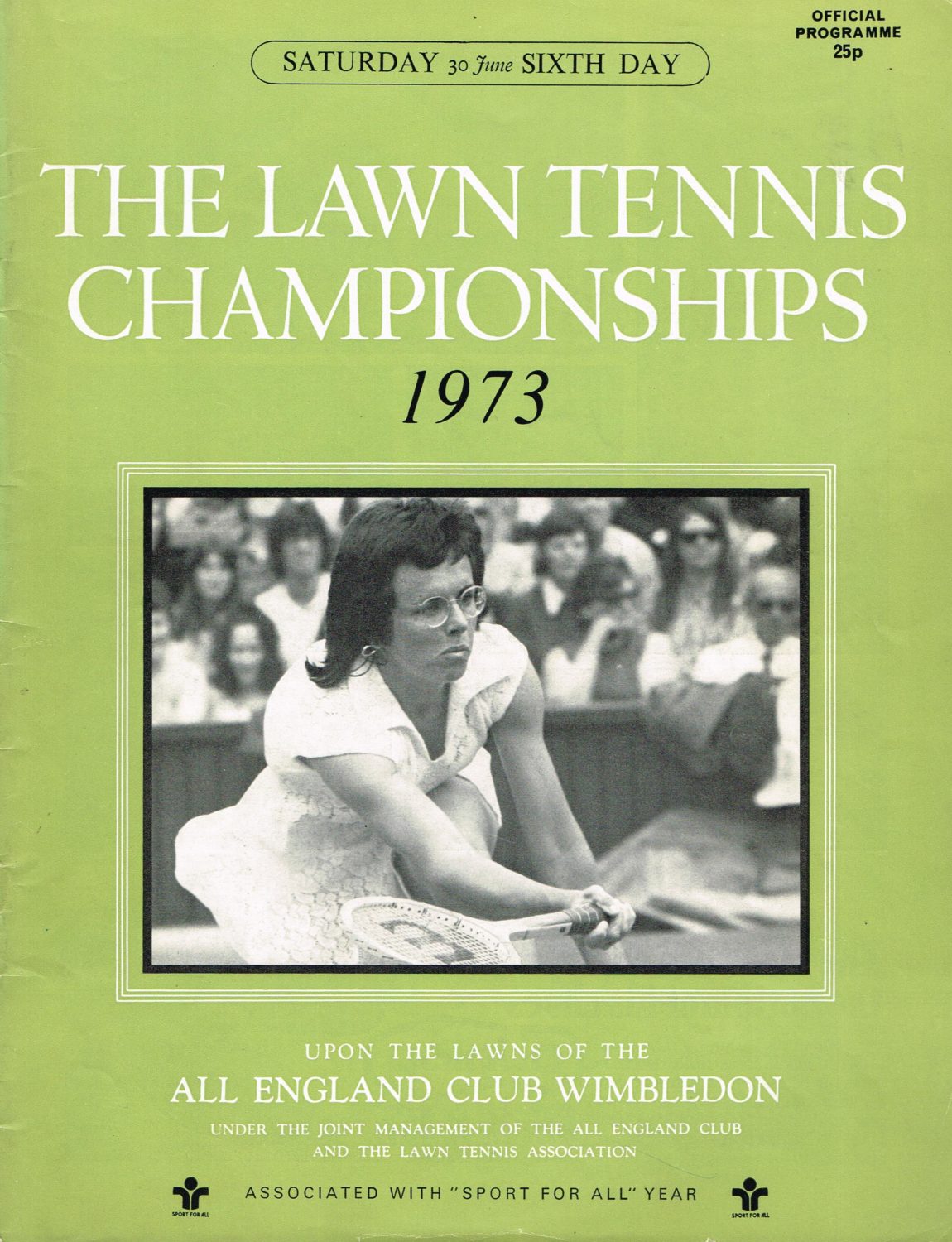

In a parallel development, the women players met in London on 21st June and formed what eventually became known as the Women’s Tennis Association, but there was no discussion of a boycott, even though leader Billie Jean King had previously said she would support the idea. The women were now the main attraction, and held a strong bargaining position. However, having only formed their Association four days before the tournament commenced, they were in no position to pursue their just claim for a greater share of Wimbledon’s prize money.

As has since become clear, the dispute was not really about Pilic. It was about the exploitation of sport for profit, particularly in North America. Cliff Drysdale, president of the ATP, said as much: “Tennis is a fast-exploding sport in the United States. It is the last great sport which hasn’t been fully exploited.”

The Wimbledon Committee need not have worried, however, for the 1973 Championships proved to be one of the most successful ever. New stars like Bjorn Borg, Alex Mayer, Jurgen Fassbender, long-haired Ray Keldie, and, of course, eventual champion Jan Kodes, replaced Newcombe, Ashe, Laver et al, and 302,000 people turned up to watch, Wimbledon’s second highest ever attendance. The dispute had been unfortunate, but it had proved that, for the British public at least, it was Wimbledon itself that was the big attraction.

Past champions Laver, Smith and Newcombe lost the opportunity to win another Wimbledon title; indeed, no male champion prior to 1973 ever won the title again. When Jack Kramer, the ATP’s leading negotiator, was fired from the BBC commentary box where he had worked alongside Dan Maskell throughout the 1960s, the popular team of ‘Jack and Dan’ was broken up. The ATP had made their point, but the players—and the TV viewers—had paid a heavy price.

But why did people turn up in such large numbers to watch? To show the ATP were wrong to strike, or to demonstrate a deep love of Wimbledon that brought people to SW19 despite the indifferent weather? I can’t speak for anyone else, but in my own case, it was definitely the latter. The previous year, 1972, had been when the ‘Wimbledon Bug’ had really bitten. I’d been to Wimbledon before, in 1969, when I saw the amazing semi-final between Laver and Ashe, when the American started with a blizzard of winners and took the first set in under 20 minutes, and again in 1970, but in 1972 I’d suddenly realised that I wanted to spend as much time here as I possibly could. I’d spent the whole year looking forward to Wimbledon 1973, and I really didn’t care who was going to be playing. It would be Wimbledon, and it would be great. I wasn’t disappointed, and I’ve been back every year since.

Story published in Courts no. 4, Summer 2023.