« Noir c’est noir, il n’y a plus d’espoir »

Premier ressenti de lecture

« Oui gris c’est gris

Et c’est fini, oh, oh,oh,oh »

La musique de Johnny chasse l’écriture

ça me rend fou,

j’ai cru à ton amour

et je perds tout…

Un mélange de genres surprenant!

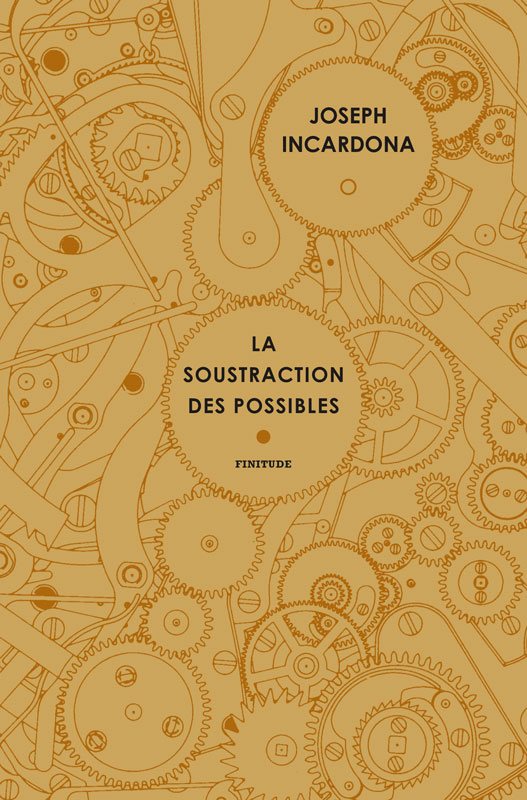

La soustraction des possibles. Du noir polar intense, des arômes de tragédie. Un roman pur et dur signé Joseph Incardona. Prix Relay. Pocket 2021. (7,95€)

Très vite, on est dedans. Happés par la fin des années 80, ce second souffle de l’ultralibéralisme où l’argent est roi et coule à flots, quitte à disparaître très vite pour ressusciter intact et à la vue de tous, sous forme de biens et d’objets convoités, propriétés, bijoux, maisons, voitures ou oeuvres d’art… Ce sont les années Thatcher et Reagan, celles de l’argent fou décrié par Alain Minc. Mondialisation heureuse et arnaques en tout genre. Le scénario est helvétique. Genève 1989.

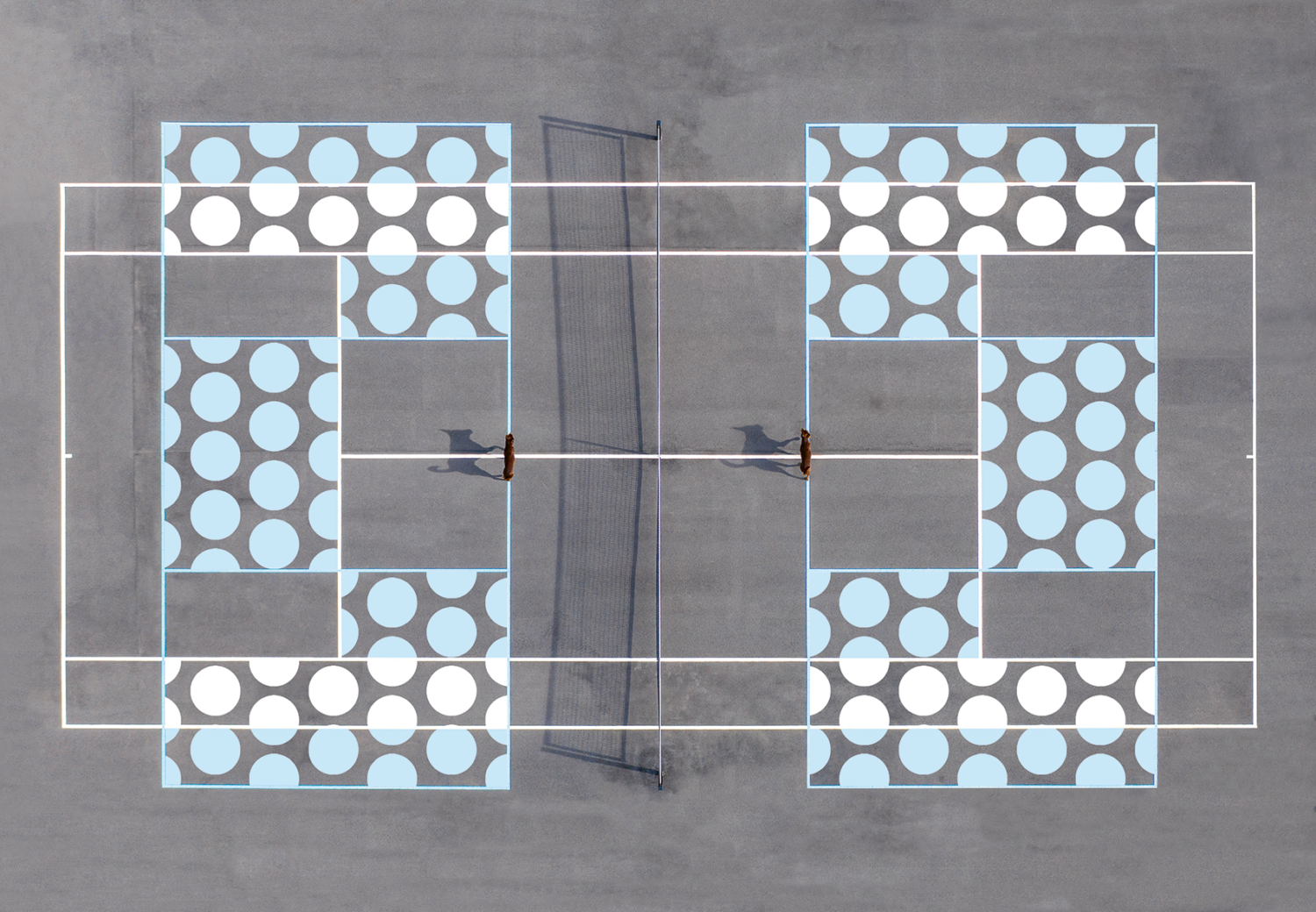

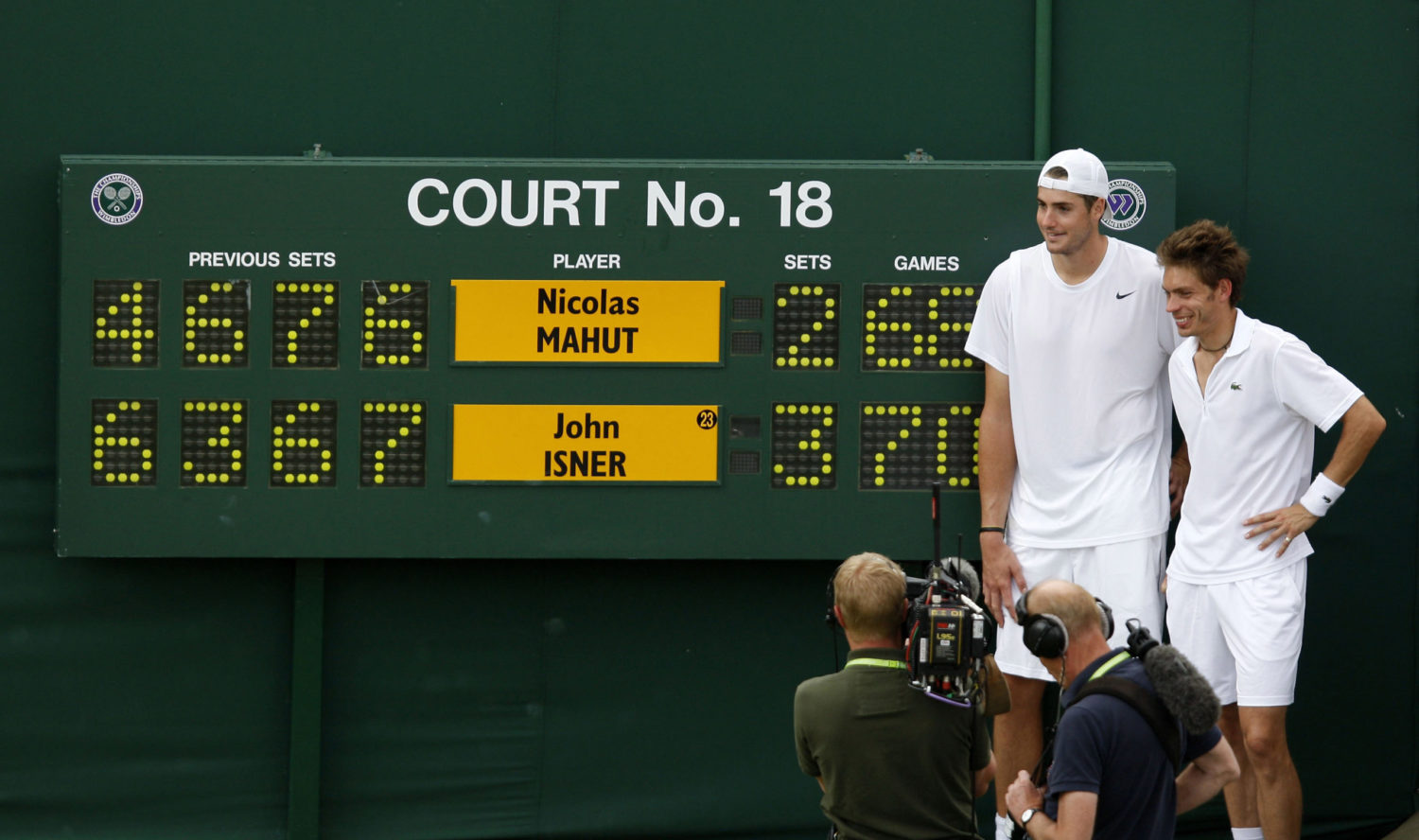

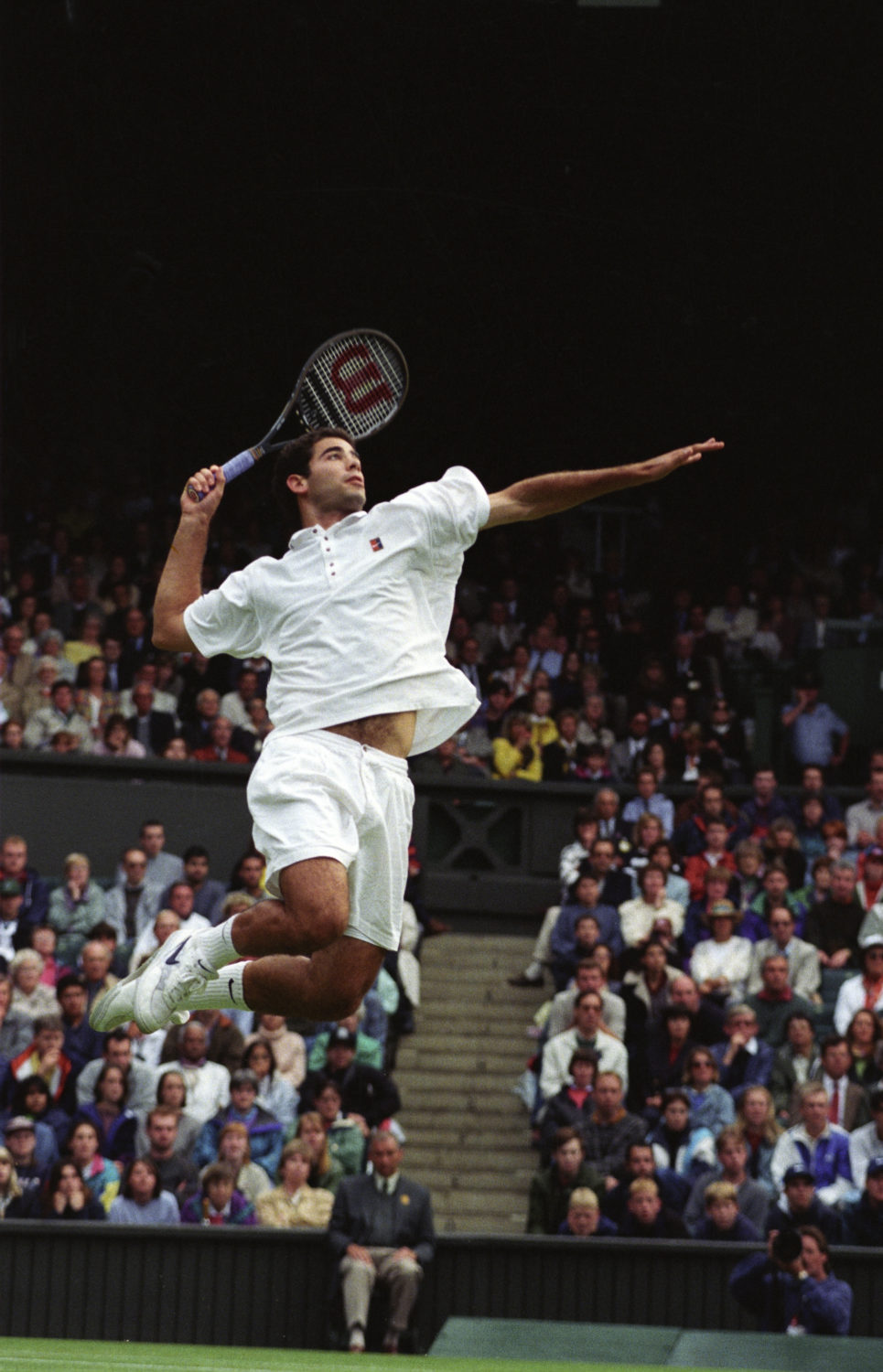

Aldo Bianchi, trente-huit ans, rital, gigolo et prof de tennis veut jouer dans la cour des grands et ramasser vite fait un paquet d’oseille, quitte à basculer dans l’illégalité. Odile, en proie à la cinquantaine, riche, soumise et humiliée par maître Aldo, est prête à tout sacrifier pour le garder. Elle lui met le pied à l’étrier. Façon de parler. Les dés sont jetés et l’aventure peut commencer.

Aldo en porte-valises. Les billets se multiplient pour mieux disparaître sans faire de vagues. Un ballet soft, bien orchestré. Tout baigne. Trop vite, trop bien. Le maestro ne voit rien venir. Il déguste vilain sur une aire d’autoroute. En prend plein la gueule. La valse des billets reprend. Sans lui. Cette fois, l’argent part dans les airs, à bord d’un deltaplane orange. Risqué, oui. Mais ingénieux. Sauf qu’il ne faut pas avoir froid aux yeux pour le transporter.

Svetlana, une jeune louve affamée survient. Pas question de se contenter des restes d’un festin. Trente cinq millions de dollars sont à portée de main. Elle rejoint Aldo dans une quête d’absolu. L’amour, l’argent, le pouvoir. Ou rien.

Prenez du Bonnie and Clyde, ajoutez un peu de Charles Bukowsky, une touche de James Hadley Chase et un soupçon de vérité. Glaçons, shaker, menthe poivrée et citron vert. Agiter avant de servir. A boire avant ou après les repas. Ne favorise pas toujours le sommeil. Déconseillé en cas de troubles hépathiques.

Bonnie and Clyde, la base. Dure à souhait. Tragique, romantique, violente. Une histoire d’amour, d’argent et de plomb.

Bukowsky pour le langage cru, la gueule de bois avant, pendant, et après l’amour. Et puis parce qu’il aime sourire à la lune et pas aux étoiles, surtout quand il est bourré d’écriture, d’alcool et de poésie.

Et Chase, incontournable. Parce que tous ses livres ou presque, commencent bien et se terminent mal à cause d’une femme, à cause de combines foireuses, à force d’en vouloir plus, toujours et encore plus. Plus d’argent, plus d’amour, plus de pouvoir, plus de reconnaissance. Mais terminé les rupins et voyous des années 60 qui peuplent les casinos de Paradise City ou de Miami. Joseph Incardona voyage un peu à Lyon et beaucoup à Genève. Du coup, ses personnages sont des financiers de haut vol, des femmes riches et esseulées, des criminels endurcis, des Albanais, des enfants d’enfoirés de Corses. Des demi pointures, des gigolos, des truands, des redoutables prostituées. Des filles de maquerelle qui manient mieux le couteau que la fourchette.

Lyon, la France. Province, bourges et gangsters. Délinquants et criminels en tout genre. L’heure est à l’intégration. Pas si sûr. Genève, ville de passage par excellence, haut lieu de la finance en transit. Opulence feutrée et rassurante. Indifférence, neutralité. Banques, chocolats.

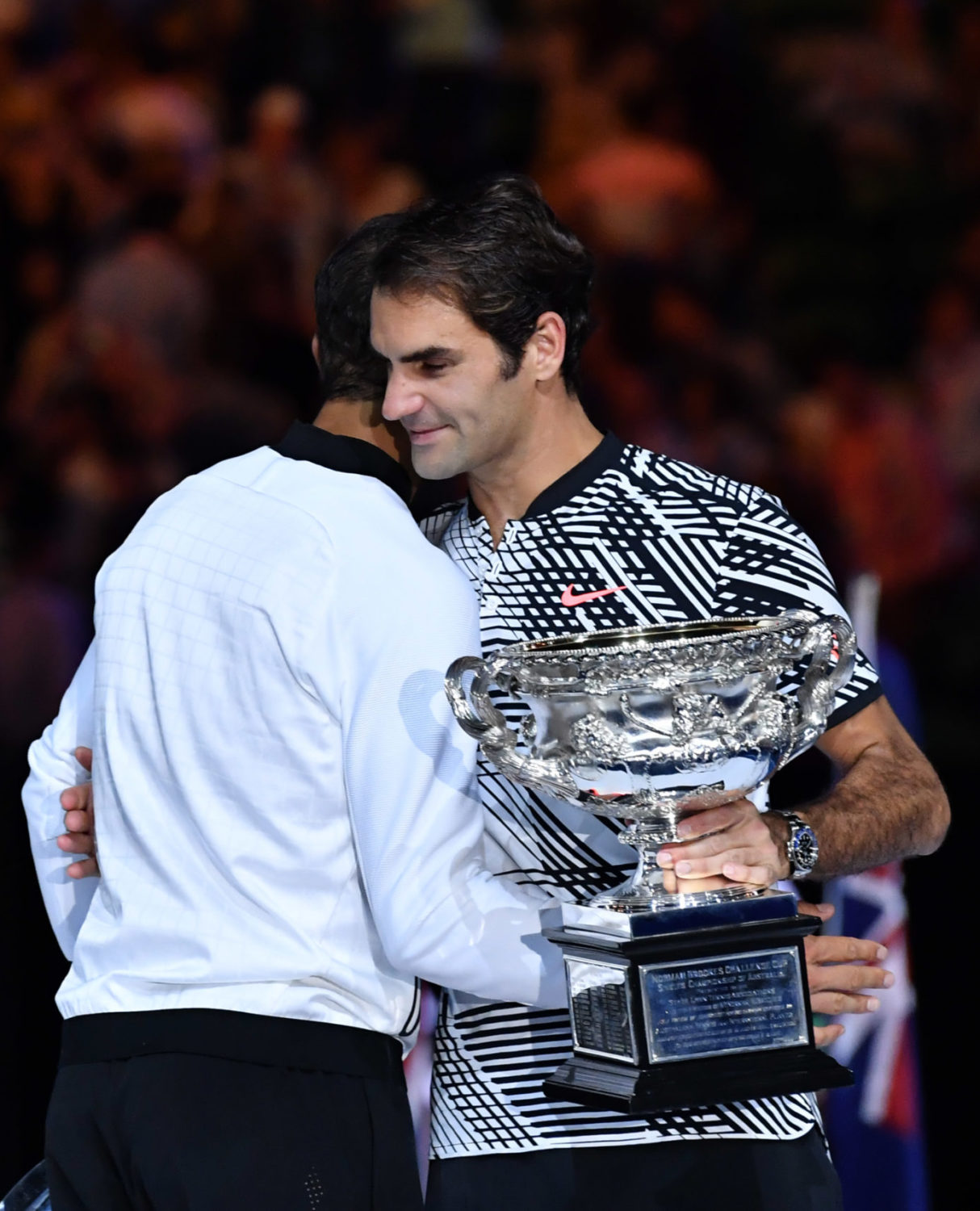

L’écriture est sèche, troublante, actuelle. Très tendance, malgré les sources classiques d’inspiration. Les mots durs, jaillissent comme des frappes. Plates, profondes, en fond de court. La balle d’Aldo, le prof de tennis est bien touchée, centrée dans sa raquette de pro. Le poids est en tête. Elle semble parfois un peu lourde. On respire l’air du temps. La fin de ces années 80. Celle de tous les possibles. On devine celui des années à venir, le début des nouvelles technologies. Une menace pour certains. Sauf qu’on travaille encore en manipulant le flux des devises étrangères. L’ère du Web est à l’horizon. Il faut se dépêcher d’agir. S’enrichir à l’ancienne, version classique, dans l’urgence. Avant que le métier ne change définitivement de mains. Tout le monde ne s’improvise pas, et les reconversions peuvent s’avérer pénibles dans un monde économique en pleine transformation.

Malveillance, malversation, mal tout court. L’écrivain dénonce. Le système politique et social, le capitalisme dur et pur, ses contraintes, ses contradictions. Le miroir inversé de la richesse. Un miroir aux alouettes. Le leurre est légion. Les pauvres d’un côté, les blindés de l’autre. La dynamique d’une économie moderne n’exige pas forcément des inégalités de patrimoine insupportables. Nul besoin de revendiquer une légitimité pour contester. Ecrire peut suffire, à condition de savoir s’y prendre, où commencer et quand s’arrêter. Incardona sait incontestablement. Il maîtrise lieu, temps et action. Venu d’ailleurs, il surgit au milieu du roman pour interpeller le lecteur et disparaître au profit de l’histoire. Ses fenêtres s’ouvrent et se referment doucement, sans bruit ni volets électriques. Un rythme déconcertant en play off. Les accords se superposent, se plaquent avec violence dans les lumières grises de l’aube. La musique disparaît dans l’obscurité d’un jour nouveau.

Le sexe catalyseur. Moteur à la fois pudique et trivial chez Incardona. Le levier du désir, l’ivresse des préliminaires, la jouissance brutale, la force et le pouvoir sont au rendez vous. L’orgasme, l’extase. Toute la poésie du banquier. Une évidence, comme l’argent. Mais aussi, surtout, et bienheureusement, l’amour. L’amour rédempteur, l’amour du Grand Pardon, l’amour fou, passionné, celui qui n’arrive qu’une fois dans la vie et que l’on recherche ensuite en vain jusqu’à la mort :“Le sexe est difficile à pratiquer et à écrire, son approche, sa complétude, ses connexions. Mais quand il se fait bien, quand Aldo et Svetlana se regardent dans les yeux tandis que leurs corps s’agitent, se cherchent et se trouvent, quand ils écarquillent leurs yeux comme s’ils voyaient le monde pour la première fois, et qu’ils viennent, jouissent ensemble comme on irait au bout du monde (…) et qu’ils fécondent la terre et que leurs gémissements traversent la campagne, les champs, la vie, alors, oui, le sexe est beau, le sexe est très beau”.

Voilà pour le lyrisme, côté jardin. Côté cour, c’est autre chose. Tout y est possible ou presque. Même un brin d’espoir. Reste à soustraire le bonheur et recompter l’addition. Elle risque d’être salée.

Joseph Incardona, classe 1969, père sicilien, mère suisse. Ecrivain, scénariste et réalisateur, il s’inspire avec succès du roman noir et de la littérature nord-américaine du XXe siècle. Auteur d’une quinzaine de livres, il remporte en 2015 le Grand Prix de Littérature policière pour Derrière les panneaux, il y a des hommes.