À la clinique du geste

De plus en plus de joueurs et de joueuses font appel à la biomécanique pour optimiser leur jeu. Une approche scientifique du geste, qui ouvre de nouvelles perspectives techniques, avec des résultats parfois spectaculaires.

Pour débuter, une devinette : outre le fait d’appartenir au top 5 mondial, quel est le point commun entre Aryna Sabalenka, Ons Jabeur et Caroline Garcia ? Ces trois championnes ont récemment consulté des spécialistes de la biomécanique, un mot compliqué pour désigner une discipline scientifique qui nous concerne tous, celle de l’étude du mouvement humain. Du lever de tasse de café à la descente de canapé, les principes de la biomécanique sont partout, dans chacune de nos actions du quotidien sans que l’on en soit conscient. « Tout ce que l’on a appris en sciences physiques s’applique au corps humain », rappelle Cyril Genevois, entraîneur, docteur en Sciences du Sport et spécialiste de cette discipline. Mais si les joueurs s’intéressent à cette science, ce n’est pas pour réviser les lois de Newton, ni pour perfectionner leur lever de coude. Le tennis, sous l’impulsion de scientifiques australiens, est devenu un objet d’étude de la biomécanique à la fin des années 90, donnant la possibilité aux techniciens d’explorer une nouvelle approche dans la quête infinie du geste parfait. « On a toujours fait de l’analyse technique. Mais la biomécanique essaie d’aller un peu plus loin en cherchant les causes et les conséquences du mouvement. Avant, on était plus sur une analyse technique descriptive un peu figée, où l’on essayait de reproduire un modèle », explique Caroline Martin, qui dirige depuis 2010 le laboratoire M2S (Mouvement Sport Santé) de Rennes, reconnu mondialement pour ses publications sur la biomécanique du service.

Du magnétoscope aux caméras opto-électroniques

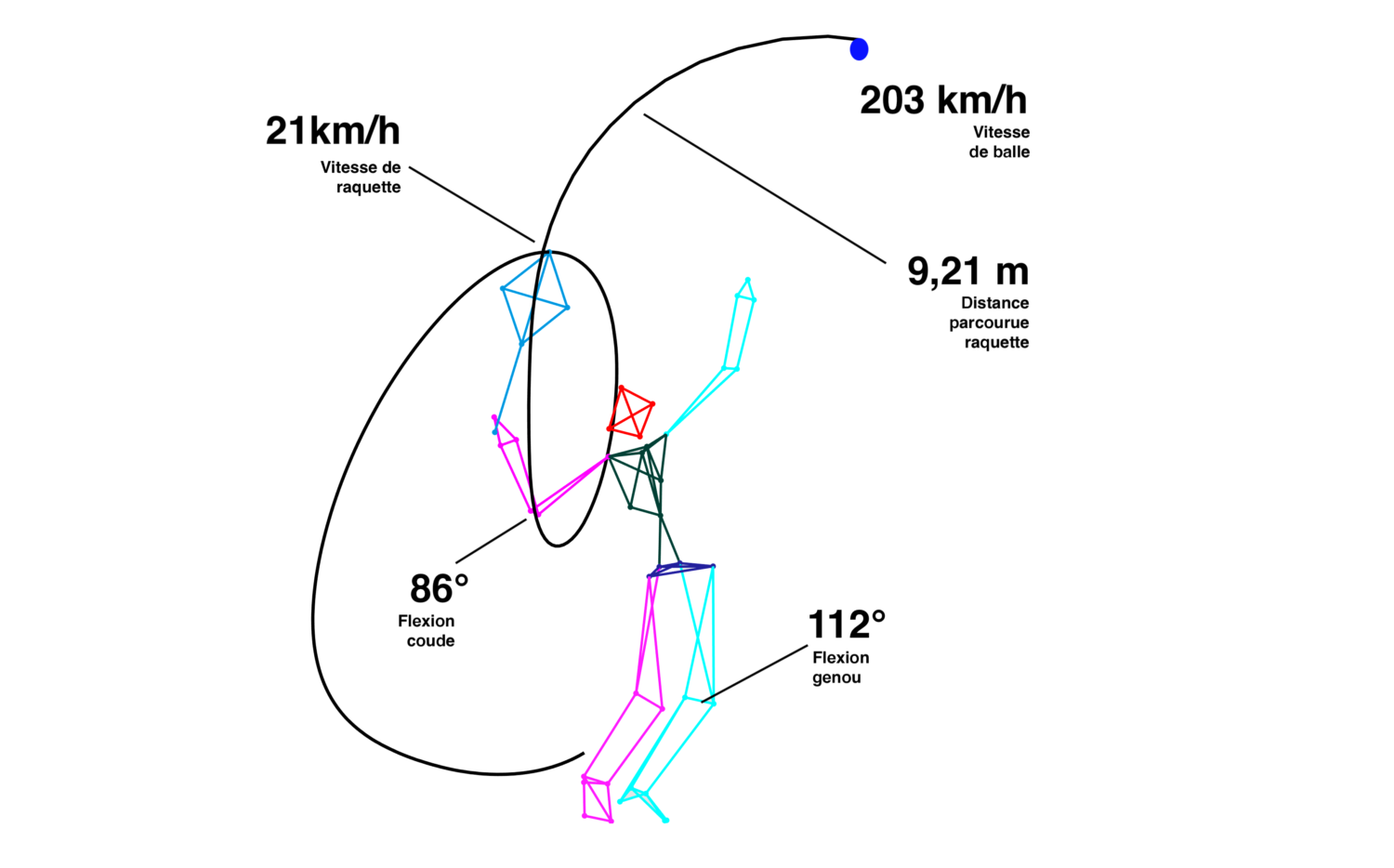

La boucle de coup droit, la prise marteau, les appuis en ligne… c’est un tennis très dogmatique et un peu rigide qui a été enseigné pendant des années à des milliers de joueurs. Facile à dire a posteriori, car à l’époque, les entraîneurs disposaient d’outils limités et du genre encombrants : « J’ai voulu analyser en vidéo les retours de service de Yannick parce que c’était une faiblesse chez lui », se souvient en rigolant Patrice Hagelauer, l’entraîneur de Yannick Noah lors de sa victoire à Roland-Garros en 1983. « Je ne vous raconte pas le matos… Il y avait un chariot de supermarché sur lequel on avait une télévision avec un magnétoscope, relié à une grosse caméra. Dès qu’on faisait un ralenti, l’image se brouillait. On a réussi à voir des trucs, mais ce n’était pas simple. » 40 ans plus tard, au laboratoire M2S de Rennes, les joueurs bénéficient d’une analyse du mouvement en trois dimensions et in situ, avec une technologie de pointe. « Notre gymnase est équipé d’une vingtaine de caméras opto-électroniques qui permettent d’enregistrer la position de marqueurs réfléchissants sur le corps des joueurs. Elles sont synchronisées pour reconstituer le mouvement du joueur en 3D. En une seconde la caméra va prendre 300 images. On a aussi un radar, des plateformes pour mesurer les forces de réaction au sol et de l’électromyographie pour les muscles en cas de blessure », énumère Caroline Martin. En 2018, cette ancienne -15 a vu débarquer à la gare de Rennes l’atypique duo formé par Daniil Medvedev et Gilles Cervara. À cette époque, le Russe est aux alentours de la 60e place mondiale et son nouvel entraîneur français hésite à entamer un chantier technique d’envergure. « J’étais dans une dynamique de réflexion par rapport au service de Daniil. Avec la biomécanique, je voulais valider mes impressions et lui permettre de constater par un moyen plus scientifique ce que je pensais distinguer », a témoigné Gilles Cervara dans l’Equipe. Convaincu par les résultats de l’analyse biomécanique, le duo a finalement opté pour une modification technique, avec le succès que l’on connaît.

Les chiffres ne mentent pas et c’est pour cette honnêteté sans faille que plus de 150 joueurs de haut niveau sont venus alimenter la base de données de Caroline Martin. « Cela permet au joueur d’être vraiment acteur de sa progression technique. On a aussi parfois l’impression de jouer sur l’aspect mental en les confortant, en leur disant : c’est bon, tu sers bien ! », se félicite-elle. L’autre atout de l’approche biomécanique, et pas des moindres, c’est d’identifier les facteurs de blessure et donc de les prévenir. « Si je sers à 200 km/h, je suis efficace. Mais si je sers à la même vitesse avec un coût énergétique moindre, avec moins de contrainte sur l’épaule, je suis plus efficient. Il y a de très grands serveurs, comme Patrick Rafter, qui ont été très efficaces mais qui en ont payé le prix, avec plusieurs opérations de l’épaule. Grâce au recul des études, on sait comment éviter des rotations trop précoces qui peuvent entraîner des blessures aux abdominaux ou à l’épaule », ajoute Cyril Genevois, qui intervient régulièrement auprès de la fédération internationale pour sensibiliser les entraîneurs à la biomécanique.

La reine de la double faute déchue

La vainqueur de l’Open d’Australie Aryna Sabalenka, elle, a eu recours à la biomécanique pour soigner un mal qui ne touche pas que les joueurs du dimanche : la crise de double faute aiguë. À l’été 2022, elle commet 23… doubles fautes lors de son premier tour (qu’elle remporte quand même !) au tournoi de San José. Découragée, celle qui s’est surnommée avec auto-dérision « la reine de la double faute » décide de faire appel à Gavin MacMillan, un spécialiste américain de la gestuelle, plutôt branché « sports US » (football américain, basket, baseball…). C’est d’ailleurs son expérience du geste du lancer au baseball qui l’a aidé à identifier le problème. « Son bras de lancer s’effondrait après le lancer. Elle aurait pu travailler avec un psychologue pendant 10 ans, ça n’aurait rien changé et je peux le prouver ! », a-t-il affirmé, sûr de lui, dans le podcast « On the line ». En tout cas, la guérison semble en bonne voie : la Biélorusse a remporté 92 % de ses jeux de service lors de son parcours victorieux à Melbourne contre 67 % en moyenne sur la saison 2022.

« On arrive à rentrer dans le subconscient pour modifier le geste »

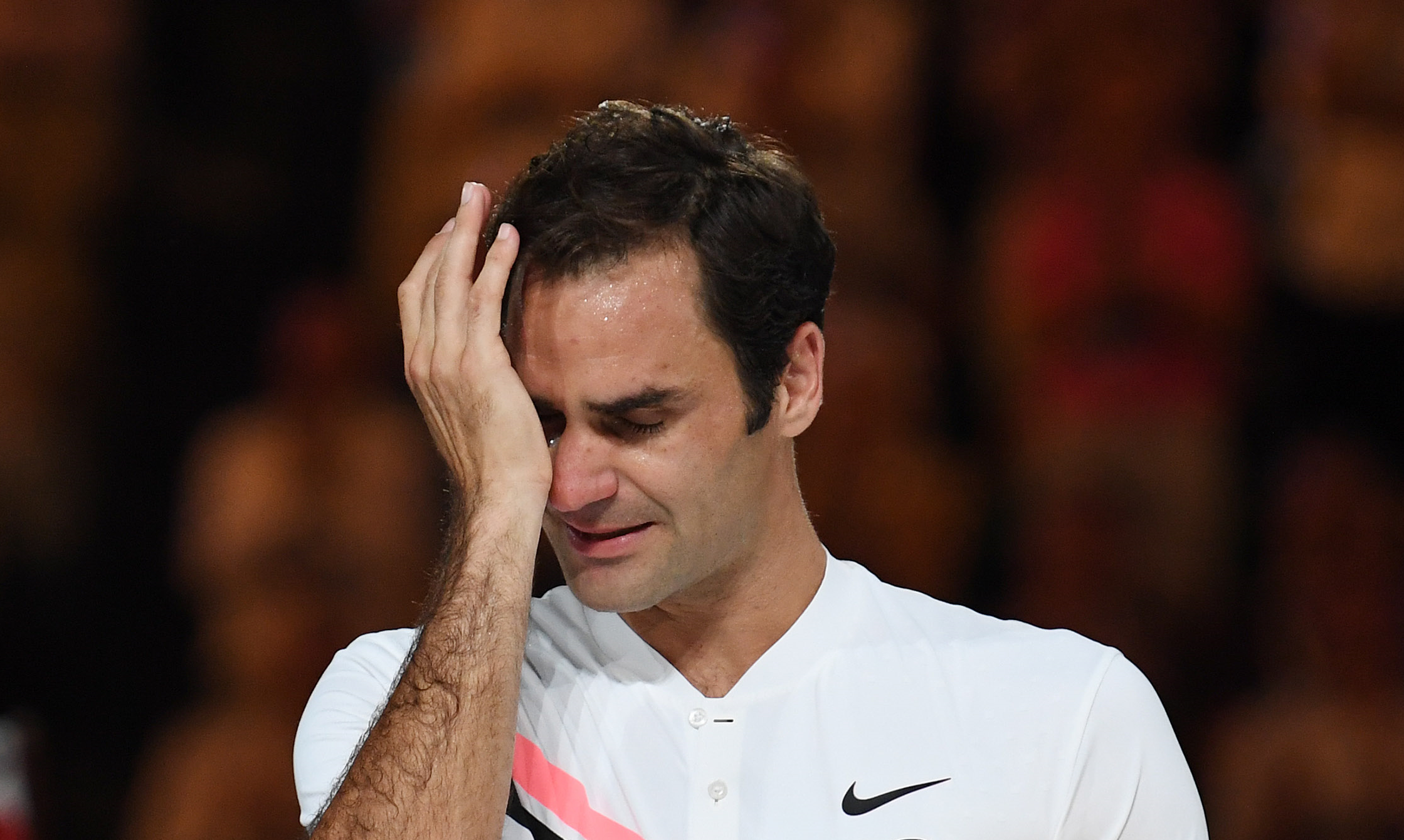

Si la biomécanique aide à poser un diagnostic, elle n’épargne pas aux joueurs un long travail de répétition à l’entraînement pour intégrer définitivement la modification du geste. Mais là encore, des méthodes innovantes permettent de raccourcir les délais. La technologie « Allyane Sport » intervient auprès des sportifs pour modifier leur gestuelle en quelques séances, grâce à la reprogrammation neuromotrice, une association de sons de basse fréquence et de visualisation. « Avec ces outils, on arrive à rentrer dans le subconscient des gens et à modifier des gestes qui sont automatiques. Nous avons modifié le départ de course de Christine Arron, ou la course du footballeur Ivan Rakitić », se félicite Paul Dorochenko qui fut, entre autres, l’ostéopathe de Roger Federer, avant de se consacrer à cette méthode. En 2021, il a rendu visite à Caroline Garcia dans son camp de base espagnol, près d’Alicante. « Caroline a un court de tennis juste à côté de son appartement, donc c’était très pratique. On décidait avec son père Louis-Paul d’un ajustement technique. Ensuite on allait dans son appartement, je lui mettais le casque avec les sons de basse fréquence pour faire passer son cerveau en mode alpha et je lui parlais en l’aidant à visualiser la modification, à ancrer le geste. Puis on repartait sur le court et on voyait si ça marchait. On avait notamment travaillé sur le coup droit. Je lui ai fait marquer la balle avec son bras gauche pour augmenter et stabiliser la rotation des épaules », nous raconte Paul Dorochenko, fier d’avoir apporté sa petite contribution aux bons résultats de la n°1 française.

La biomécanique peut-elle amener le tennis dans une nouvelle dimension ? Les progrès technologiques devraient bientôt permettre d’analyser le mouvement des joueurs en compétition, si le règlement l’autorise. Et donc de mesurer les effets de la fatigue sur la performance gestuelle. Imaginer des joueurs ayant accès à leurs propres data biomécaniques en plein match n’a rien de la science-fiction. Une perspective qui n’enchante guère les puristes et qui interroge sur les conséquences d’un tennis « augmenté ». Toujours plus loin, toujours plus fort, le progrès scientifique est-il la condition du bonheur tennistique ?

Vous avez quatre heures…

Caroline Martin : « Le service a atteint une sorte d’optimal technique. »

Spécialiste de la biomécanique du service, Caroline Martin n’imagine pas une nouvelle révolution technique de ce geste.

Courts : Peut-on imaginer l’invention d’une nouvelle technique révolutionnaire au service ?

C.M : Honnêtement, pour le service, avec ce règlement et ce matériel, on a atteint une sorte d’optimal technique. S’il y avait un changement réglementaire, comme une seule balle au service ou un filet plus haut, cela pourrait engendrer un changement de technique. La seule révolution qu’on voit actuellement, c’est le service à la cuillère, qui est utilisé de temps en temps contre des joueurs qui se mettent très loin en retour.

C : Quid du service façon volleyball, avec prise d’élan et saut en extension ?

C.M : Il y a un joueur américain qui le faisait, Brian Battistone (88e mondial en double en 2010) avec une raquette double manche. Est-ce l’avenir du tennis ? Je ne pense pas, car les joueurs sont déjà assez grands pour ne pas avoir besoin de décoller aussi haut. C’est un service très énergivore. Ce sont de grosses impulsions et il faut enchaîner derrière. Le rapport coût – bénéfice n’est pas forcément positif. Si ça avait dû être le futur du tennis, beaucoup de joueurs s’en seraient emparés.

C : Si tous les joueurs consultent des bioméca- niciens, peut-on craindre une uniformisation de la gestuelle ?

C.M : Non, il n’y a pas d’uniformisation du geste, car on n’essaie pas d’appliquer le même modèle de service à tous les joueurs. Les conseils sont personnalisés, cela dépend des gabarits, des sensations. Il n’y a pas deux services identiques.

Article publié dans COURTS n° 14, printemps 2023.