McEnroe

through Barney Douglas’s lens

“I’m in New York, and anyone who’s seen the film Ghostbusters will be familiar with the Manhattan apartment scene, where the ghost dogs are on top of the building. That is John’s [McEnroe’s] apartment building, so that was quite amusing! I walked in, entered the elevator which took me all the way up to the top and the doors opened into John’s flat. He greeted me, saying “come in, come in”, wearing a dressing gown and slippers, and it was obvious that he’d had a big night the night before. That was the first time I met John, in the flesh.”

It is August 2022, and on a sunny Friday afternoon in London, Barney Douglas and I are chatting about McEnroe, the documentary film that he wrote and directed, which was released in the UK in July and in the US in September 2022. The film has had an outstanding reception (including a Sports Emmy Award since this interview—see end of article for details), and our interview kicks off with Douglas’s first impressions upon meeting John McEnroe in his New York apartment to pitch the film.

I congratulate Douglas on the film’s success (see end for list of accolades earned) and make a humble confession: when I received the invite for the private screening preview, I had low expectations. As a tennis fan and a writer, I’d read McEnroe’s autobiographies and biographies, watched the documentaries and films, and listened to his outspoken and uninhibited tennis commentary over the years. Was there much more to learn about McEnroe? Thankfully, I stood corrected, because Douglas’s documentary surpasses anything previously done about McEnroe. It focuses on McEnroe’s vulnerability and humanity, and delves into his psyche, something we have not been privy to before. And for that very reason, the film is captivating from the start. I came away with a deeper, profound understanding and respect for ‘Johnny Mac’.

London’s Charlotte Street Hotel was the venue for the private screening, a week after Wimbledon 2022 was put to bed for another year. Perfect timing, therefore, to satiate my tennis cravings. The film is raw and thought-provoking, stylistically transporting us into McEnroe’s world. Douglas and the film’s producers were at the screening, with an engaging introduction from Douglas. The relationship between a film director and their subject is based on infinite trust. But it becomes evident during our interview that McEnroe does not easily trust people. He will expect anyone he is working with to know their stuff and get to the point. Douglas’s job of pitching this film was therefore never going to be easy.

However, whilst chatting to Douglas, it is clear why McEnroe entrusted him to make this film and allowed him into his world: Douglas is easy to talk to, open, warm, and funny. What you see is what you get. Douglas has done his homework and come prepared.

Courts: Firstly, congratulations. Your film has had a great reception, with excellent reviews. You must be very proud!

Douglas: I am really proud. It’s always a relief when the film finds an audience, and the people that you respect appreciate and understand its purpose. There have been some big hitters behind this film, which is lovely because it isn’t your traditional documentary. It tries to push the form a little and is a bit bold. There are a lot of preconceptions about John, aren’t there? Many people are used to seeing him in a certain way visually, with a preconceived idea of who he is. So, the film provokes discussion about those preconceived ideas, and challenges some of those opinions. It shows his flaws, but also his humanity. I don’t think the production team could have done a better job with this story. We also made the film during a pandemic which had its own challenges, so yeah, I’m very proud.

C: I’m interested in what you just said about people’s preconceived ideas about McEnroe. How does your film challenge or change those ideas?

D: I wanted to make this film because John was at a point in life where he was prepared to talk more openly. The producer Victoria Barrell, who you met at the screening, suggested I pitch the film to John. It was then up to me to get on board and come up with the creative aspects. That was the first challenge, but the second one rolls into your question, as I’m only interested in the humanity of a story and the different shades of a person. Whether that person plays a sport to great success, or whether they work in a shop, the thing that connects that story to everybody else is the common ground of humanity, flaws, mistakes, love, and regret, and all those kinds of things. That’s what I wanted to explore with John. There was no way that somebody as good a player and as polarising as he was, did not have all those facets of a personality. So, I do think you discover a lot more about him through the film. For example, there is a scene where his wife Patty says she feels her husband is potentially neurodivergent. To me, all the evidence is there to suggest that that’s a possibility: John looks at the world in a different way, struggles with connection and with intense situations. You start to understand John differently. You also learn that he’s changed as a person and learnt from life and its messiness. So, for me the film becomes a parable almost to himself to not lose the connections with his own kids that perhaps he lost with his own father. It’s all those messy things that interested me.

C: Tell me more about your first impressions of meeting McEnroe. Was he different to what you imagined him to be?

D: I obviously knew the name McEnroe and, like most people, was vaguely aware of the tail end of his career, his reputation, etc. But I didn’t have extensive tennis love or knowledge, so I was able to work without that baggage. The first time I met John in the flesh was, as mentioned, at his Manhattan apartment, and we sat around his kitchen table. He asked me what I wanted to do, and I could tell he was sizing me up and analysing and testing what I was saying. I was pretty direct and honest. I think he responded well to that because I think he sniffs out people who are not direct. I learnt very early on that John wanted clear direction. When we were filming with him around the city in New York, I needed to keep him updated on what we were doing, and how long it would take. So, I stuck to that as the template for the whole process, and I listened to him as John gets frustrated when he’s not listened to. Whilst he doesn’t expect to be agreed with all the time, he wants to feel heard. I was very aware of that and ensured that I listened to his input. If I didn’t agree with something, I would say why, which he respected.

C: I know that he’s invested well in art, post- tennis. I imagine that apartment must have the best artwork?

D: Yes, there are beautiful works on the wall, and he’s got great taste. He’s bold, with all the things that you would expect from somebody like John, he knows what he likes. He has a beautiful view over Central Park as well, so he’s done well.

C: How long did you spend filming in New York, tell me about the process and what were your main challenges?

D: That’s a good question. We went back and forth a little bit, but we were very restricted with travel, due to the pandemic. We filmed it in intense short bursts. Our first shoot was planned to the enth degree! We quarantined, we planned where we were going to film, how long it was going to take, the shots we were going to do. We did the New York filming in one night, and then filmed with John the next night. The main interview took two days, which we did in two hour blocks, with breaks in between. I particularly loved the last hour of the second day because that’s how long it took for John to relax with us, trust the conversation and get to where we wanted to with him. I had more of a conversation and connection with him than a journalist, which he may have viewed me as initially, so I wanted to get away from the media interview format and have more of a connection. It took some time, but we got there.

A tight budget and the pandemic were our challenges. Paddy Kelly, one of our producers, helped with the logistics. We had to find a way to communicate and get John to reveal things about himself that we could tell in the most entertaining way possible. The difficulty was how to end the film because his career is front-loaded, and there is no ‘finishing on a high’. So for me, the walking through the streets of New York from dusk till dawn was helpful to provide a spine for the film and a natural endpoint in Patty [his wife]—this woman who, I think, in many ways, kind of saved his life. So, there’s a love story, starting from his childhood home to the place he lives in now as the sun rises. For me, that’s a very cinematic start and end. That’s what gave me the structure I needed. Another challenge was the logistics of speaking with John and planning what we needed to communicate, etc.

C: It’s evident that McEnroe entrusted you to allow access to his nearest and dearest. I found the film more revealing than anything I’ve seen or read about him previously. His children speak frankly about McEnroe as a father, and I was very surprised when Patty Smyth reveals that she has always felt he is on the autism spectrum. How did you earn his trust for him to open up in the way that he did?

D: When filming, you have to create an environment that will enable the subject to slowly open up and explore something in the journey. I don’t think for a second that John went in thinking that this was what was going to happen. For me, the last 20 minutes of the film are like a therapy session, where it really feels like he’s discovering stuff. That is very much what I wanted to get to as a filmmaker. I didn’t want it to be a pre-thought thing where John decided what he would say. It took time to get to because as a skilled broadcaster, John is used to bite-size pieces of information, trotting out the same stories, etc. I had to get past that and bring his energy down and start to find ways into this maze in a different way. For example, he struggled with my question ‘what do you think love is?’ but that turned the conversation into a different direction and that’s what I’m always looking for really. I don’t think he set out for it to be this raw. But as you said, he’s a very authentic, open person and I earned that trust by helping him understand that the documentary wasn’t going to be used against him in a way that was unfair.

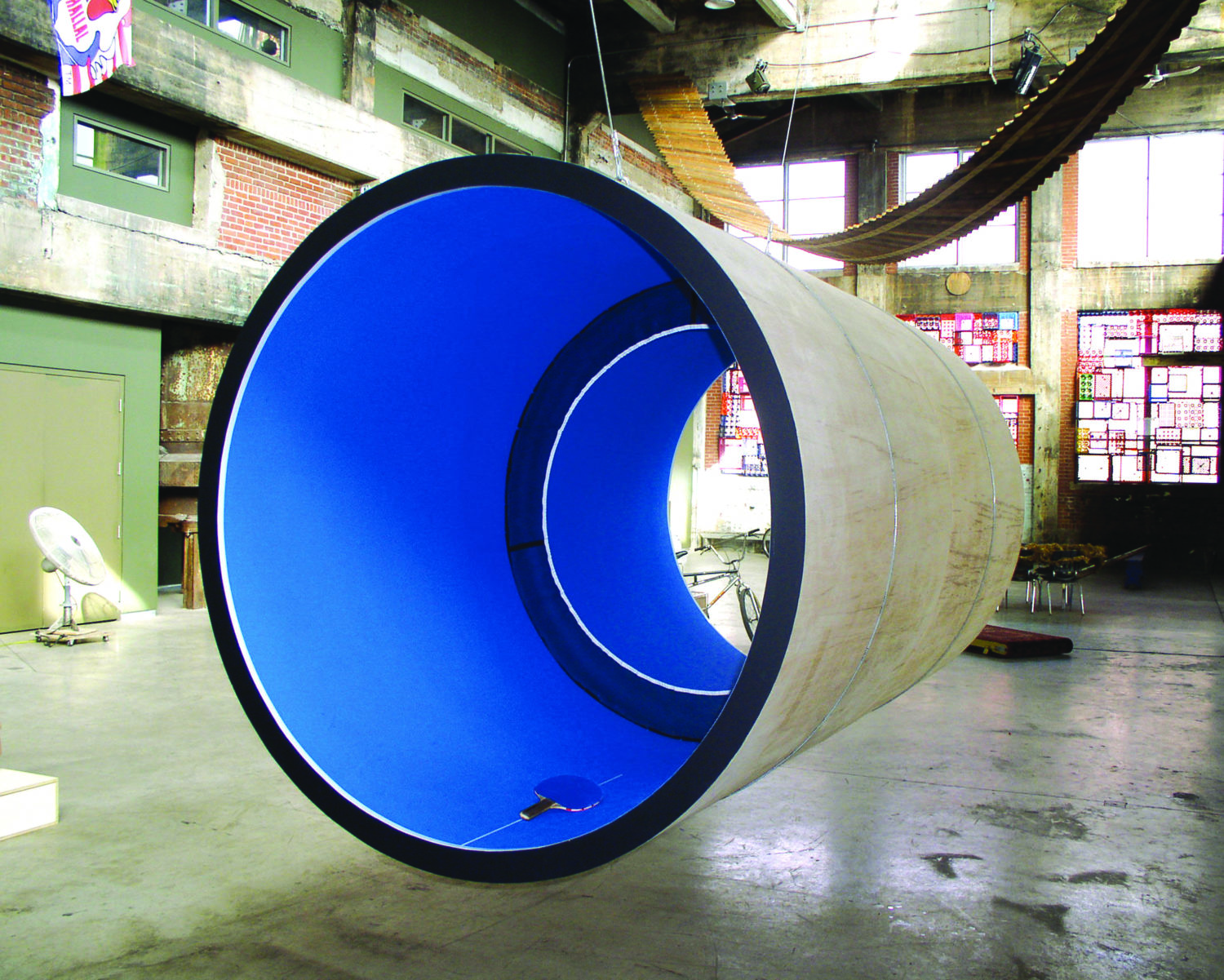

C: I love the metaphorical scenes with computer graphics converting a tennis court into a chessboard, or a map of McEnroe’s brain! And the vibe of McEnroe walking through the New York streets at night (I noticed, wearing vintage Nike sneakers from the 80’s). Tell me about the creative process behind this.

D: Well, there was another advert from a similar time, showing John in a long coat walking through Times Square. That was one of the early images that I saw of him. When making a film, I usually get an image which leaves an impression on me and then everything almost blossoms from there. Well, that was the image that set me on that path. I then looked at 80s and 90s New York films which brought the visual aesthetic to include all those things that I wanted to see in New York at night. I wanted the city to be empty. I wanted it to look like we were wandering through the mind of McEnroe. I wanted to elevate the visual level of the film beyond the normal sports biopic-type film, into something very cinematic. By evoking the era, we used graphics that were inspired by aesthetics like the 80’s sci-fi film Tron. That’s where it all started.

C: You captured that vibe so well. I love the music score, especially during the Gerulaitis partying years. The music elevated the atmosphere of the film. Did you have input into that?

D: Music to me is so fundamental in cinema. You can have a pretty mundane piece of footage, but with the right music, it can mean so much more. For me it was always a big part of it. Every element of the film, the sound design, the graphics, everything needed to fit well and elevate it. I love being involved in the music and working with Felix White [the composer] is a joy. Felix was formally in a band called the Maccabees. He’s a terrific, creative, open sort of person who really understood the heart of the film and what I was trying to get to. We worked very closely, sending bits of music back and forth via our iPhones, including clips of film imagery. I’d send him colours, saying, “I want it to sound like this colour”. That creativity to me is a really fun part of filmmaking.

C: There are big name contributions from Borg, Billie Jean King, Federer, and Nadal. Borg’s extensive contribution is a testament to their close friendship, as he is known to be interview shy. Some of the scenes featuring Borg on a Swedish jetty were so calming—almost matching the subject to his surroundings. How did you convince Borg to give so much of his time?

D: You’re right when you say that Borg respects John so much. They had a tremendous connection over so many years, and John is one of the few people that Borg will open up about and be more heartfelt about than anyone else. To have him in that calming environment kept him relaxed, and it was good cinematically, too. He is a really lovely guy. There are little things he reveals in his interview which hint at a deeper unexplored Borg (when he talks about death threats, walking through kitchens, walking away from tennis). But maybe that’s for someone else to explore more deeply. Borg’s filming took longer because of pandemic travel restrictions—we had to travel through Iceland to get into Sweden. Billie Jean King loves John. She was very keen to contribute and is probably my favourite interview because she is such a great storyteller—poetic, strong, and characterful with a great voice. She was fantastic. I wanted to feature people that knew John intimately, rather than those in the tennis media who would only tell you what they thought he was like.

C: Whilst working with him, was there something you observed about McEnroe that people would be surprised to know?

D: I found John challenging, but I really liked him. I liked his almost child-like insecurity. Like there’s a little boy still there for me. I don’t at all mean that in a disrespectful way, it is a very charming element of his personality. He seeks assurance from certain people around him—from people who he respects. I definitely feel that he is really misunderstood. Part of that is his fault, and part of that isn’t. It’s just a natural inability to connect in the right way that other people find acceptable. I think a lot of what he says comes from a good place and a good heart. I have a lot of empathy and sympathy in that respect for John, but I also love the fact that he’s authentic to the core, and not manipulating anything.

C: That’s lovely to hear. In that way, I suppose he’s a true New Yorker, in his frankness—what you see is what you get. In stark contrast to us, Brits, who are culturally more reserved, New Yorkers say it as it is!

D: Exactly. And that’s hard for a creative British person because a British person would do everything to ensure that someone’s not offended about something. So, you have to grow a thick skin pretty quickly when you’re making a film with John McEnroe and Patty and his family because they’re certainly going to tell you what they think! And that’s scary, but actually, once you’re used to it, it’s actually very useful. It’s very helpful.

C: Has making this film sparked an interest in you to make another tennis documentary? If so, who would be your choice of current player?

D: That’s a tricky one, because I’d prefer to do a film on another past player, like Bjorn Borg. I think there’s a deep well with Borg that’s untapped. I’m less interested in current players because character-wise, I feel today’s tennis has become more ‘corporate’. I like working with an archive—there’s something so immersive and romantic about old film and beautiful film being restored and all that kind of stuff. However, if I had to do it, I really like Andy Murray, but it’s kind of already been done, hasn’t it? Djokovic’s character, background and childhood are interesting. Kyrgios is also fascinating and people like him because they often relate him to John. He’s the most cinematically explosive, as there are so many questions around him, so I think there’s definitely something to be done there, but I’m drawn to the more romantic ages.

C: Your choice of Borg is interesting. The advantage, if you were to do a film on him, would be that you have already worked with him and built a rapport. This would also be a perfect combination after this film, wouldn’t it?

D: Yes, that would be some sequel, wouldn’t it! Actually, we did have a few interesting ideas in terms of how to make it a connected sequel which does interest me. Whether another tennis film is the right thing for me to do next, I’m not sure, but who knows? At the moment, I’m working on an ambitious documentary film about the environment, which is away from sport, and which I’m really excited and passionate about. I’d love to do two films at once, so I’m always open minded. You never know what is going to attract you. Sometimes, it’s that human element, as we’ve both said, that really sparks something.

C: And finally, your passion for this film has been so inspiring. I’ve loved learning about the process. It has been a pleasure meeting you and thank you so much for your time!

D: You’ve got to follow your passion. That’s how I started doing documentaries. I just had to make it happen, like you. I did other work at the same time, and you sort of inch your way forward, don’t you? And I don’t think you do that stuff if you don’t love storytelling essentially, which obviously is what writing is. So yeah, if you got that passion, then you just gotta keep going!

Story published in Courts no. 4, Summer 2023.

Since this interview, McEnroe the film won the Sports Emmy Award for Outstanding Long Form Editing on 22 May 2023. It has also had the following accolades:

EE BAFTA 2023 Longlist—Best documentary

1 x Producers Guild Nomination—Best documentary

2 x Critics Choice Nominations (for Best Sports Documentary and Best Cinematography)

3 x Sports Emmy Nominations (for Best Editing (winner), Best Music Direction, Best Graphics/VFX).