“touchtennis is one of the most exciting new sports out there. It is a combination of the physicality and speed of squash combined with the ability to play the sort of tennis you can only dream about on a normal court, and that’s what makes it so fun.”

Bear Grylls OBE, GQ Magazine

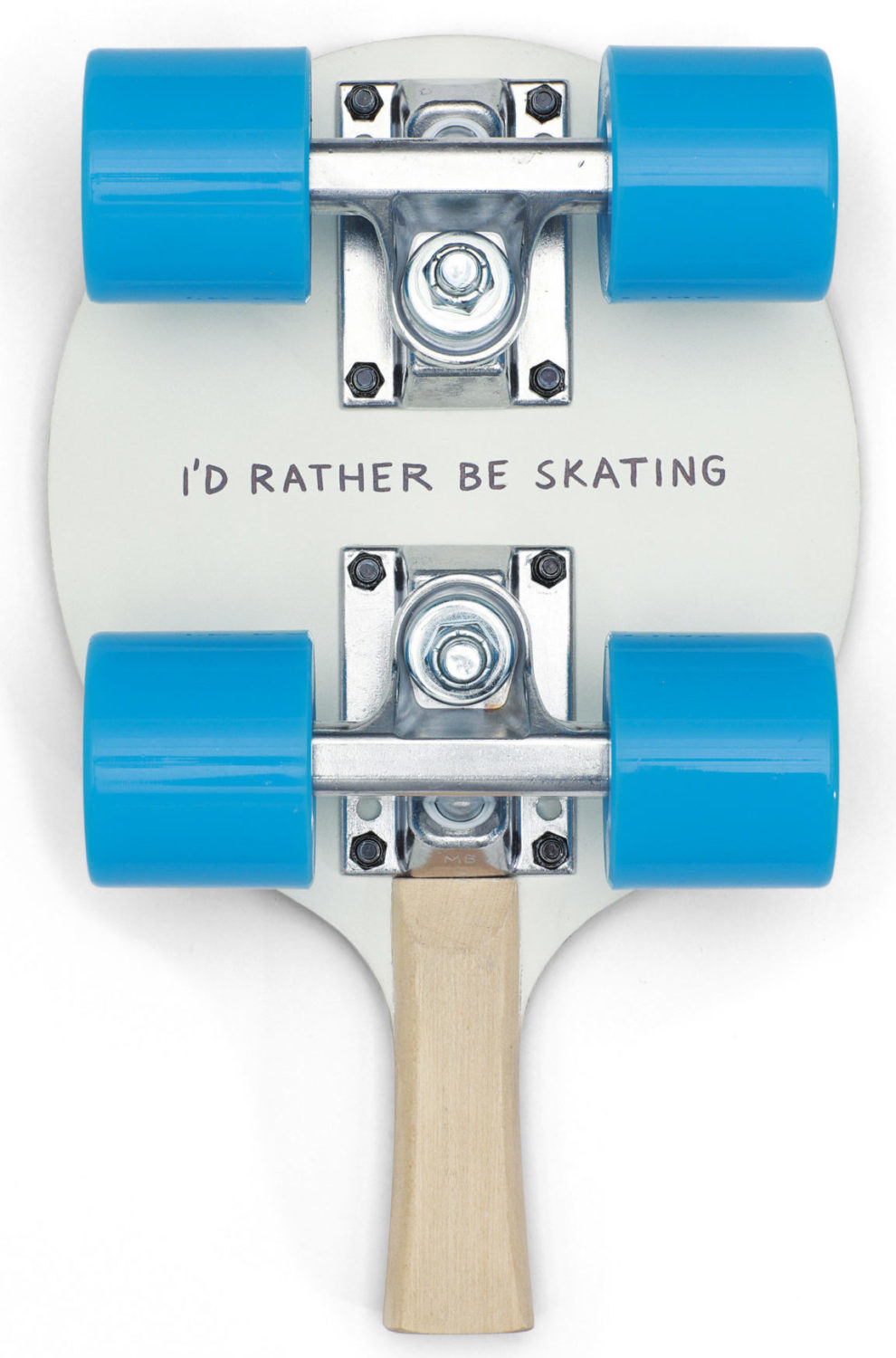

When you associate the word tennis with the acronym G.O.A.T (Greatest of All Time), a few names automatically spring to mind. Names like Federer, Williams, Graf, and Sampras. But search ‘touchtennis’ online and another G.O.A.T regularly emerges: Rashid Ahmad. Such is the symbiosis between Ahmad and the acronym, that he has even designed and recently released a new and improved touchtennis racquet, quite suitably branded the ‘Goat’ racquet.

Ahmad is founder, and self-proclaimed G.O.A.T of touchtennis, the racquet sport he cobbled together in 2002, fast gaining traction worldwide including a celebrity following. At the time of this interview, touchtennis’s Instagram account stands at over 40k followers. Our interview takes place on a cold British Spring day in May, a month before the long-awaited restart of the British summer tennis season after a year’s hiatus due to the global pandemic. Remarkably, the sale of touchtennis products surged during lockdown. Ahmad explains, “touchtennis is the only adaptation of tennis that you can play in your garden with full strokes, hit the ball really hard, and get that gratification, so take up of touchtennis was crazy.”

Adhering to UK lockdown rules, we meet virtually over Zoom. In pre-pandemic times, we would have met at touchtennis headquarters, a beautifully converted barn in Guildford. Ahmad takes me on a virtual tour of a hugely impressive set up of office space upstairs resembling a film studio with an impressive array of camera paraphernalia, thanks to Ahmad’s technology obsession. But what truly grabs my attention is a court beneath that looks like nothing I have seen before. It would not look out of place in Henry VIII’s Hampton Court Palace, with a magnificent high wooden beam roof and clay hued carpet surface. But modern and without the pomp. For today’s world, much like this relatively new racquet sport. Much like the founder himself.

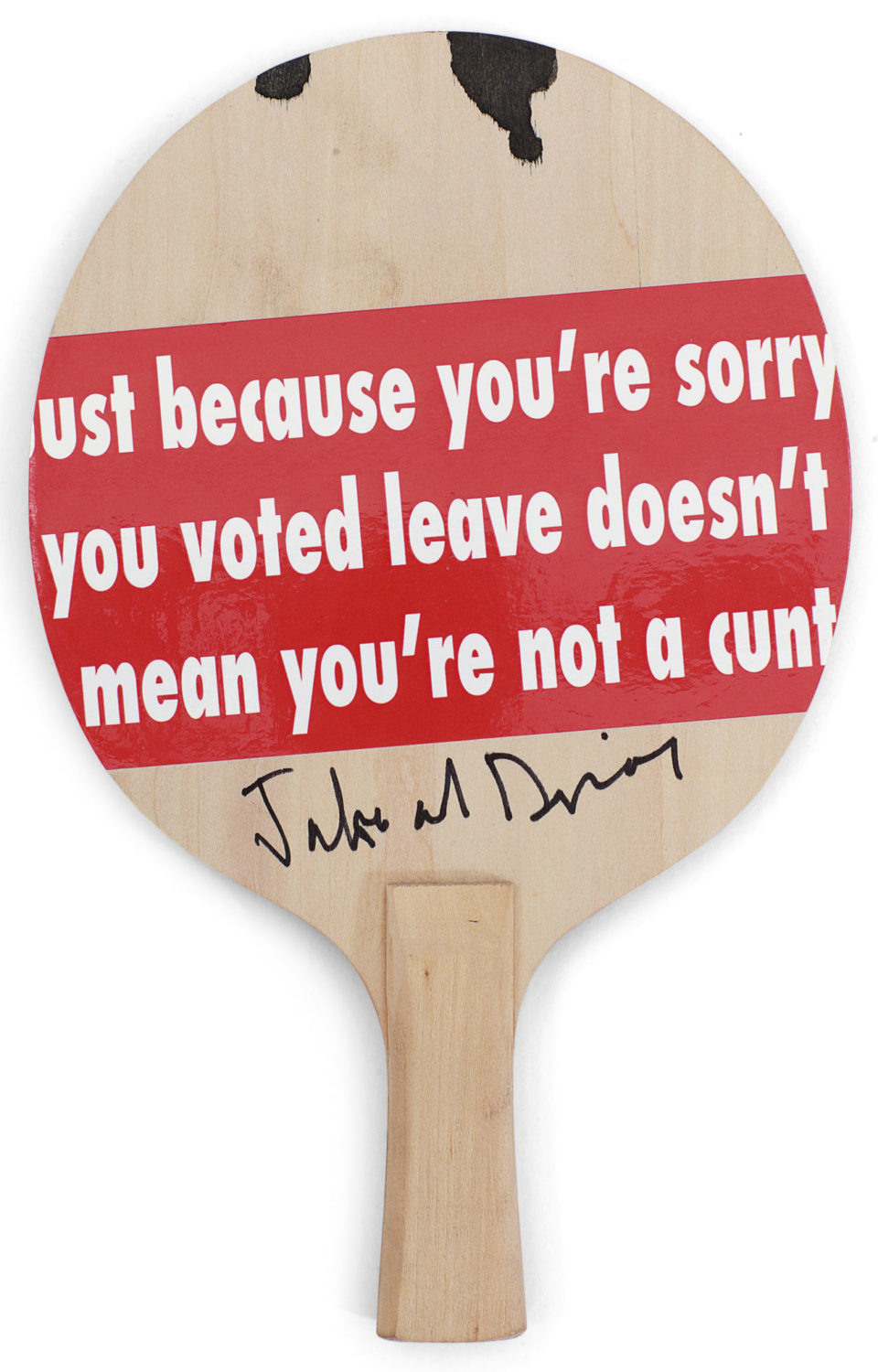

Despite self-assuredly reminding me several times during our meeting that he is the G.O.A.T of this sport, reminiscing in detail about the various slams where he “cuffed” his (under the age of 10) opponents, I find Ahmad refreshingly honest, intelligent, disarmingly charming and at times hilarious. During our chat, it becomes immediately obvious that he lives by his “raison d’être” and the quote on his Goat racquet. Whilst tongue in cheek for the G.O.A.T moniker above, it is in fact something he lives by: “stay humble”.

And the beginnings of this sport are indeed humble. To understand touchtennis is to know its founder. There were no privileges. Ahmad grew up on a London council estate in the 1970s, where football and cricket were the only sports played by local children in the car park. His tennis passion came from his father, an avid tennis fan who Ahmad would watch and discuss tennis with. Occasionally, he would go to a large brick wall on the side of an abandoned factory with his friends, where he would “just hit tennis balls with any racquet that anyone had, like a £2 racquet from the newsagent. I could never afford to play tennis because membership to a club was out of the question. The nearest courts were in Regents Park, charging £3. Where were we going to find £3 to play, plus buy balls and equipment? Forget it! Touchtennis is a natural evolution from that lack of space and a sport that is accessible to everyone”. The seed was planted, with a family connection: touchtennis sprang from teaching his daughter using this adaptation and playing it with friends in his garden. His brother is credited with the name.

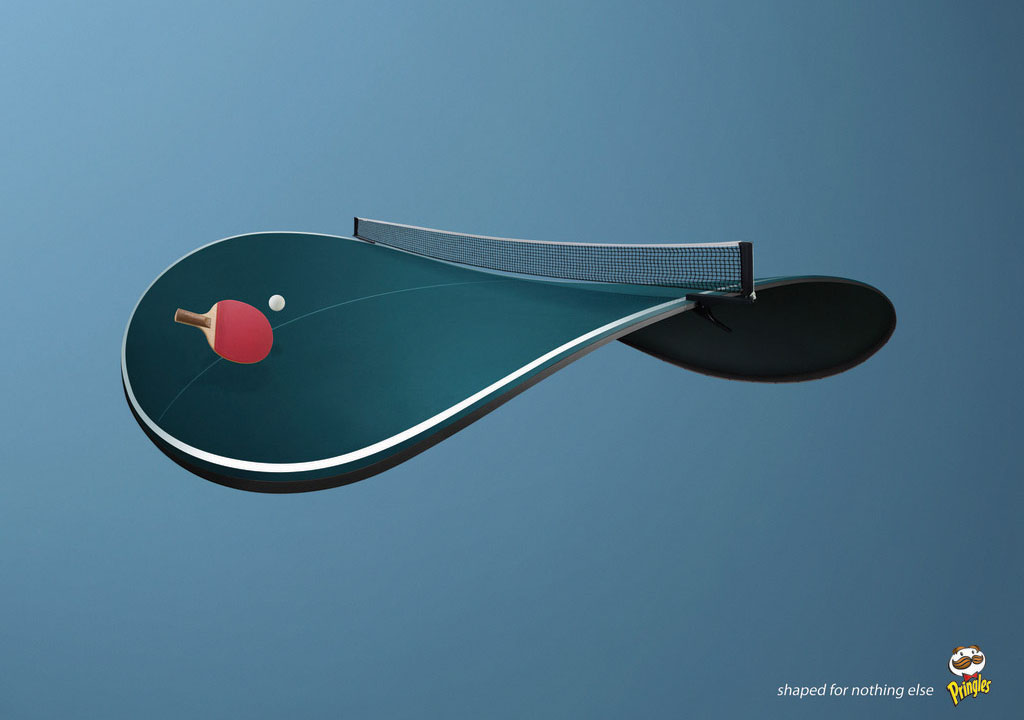

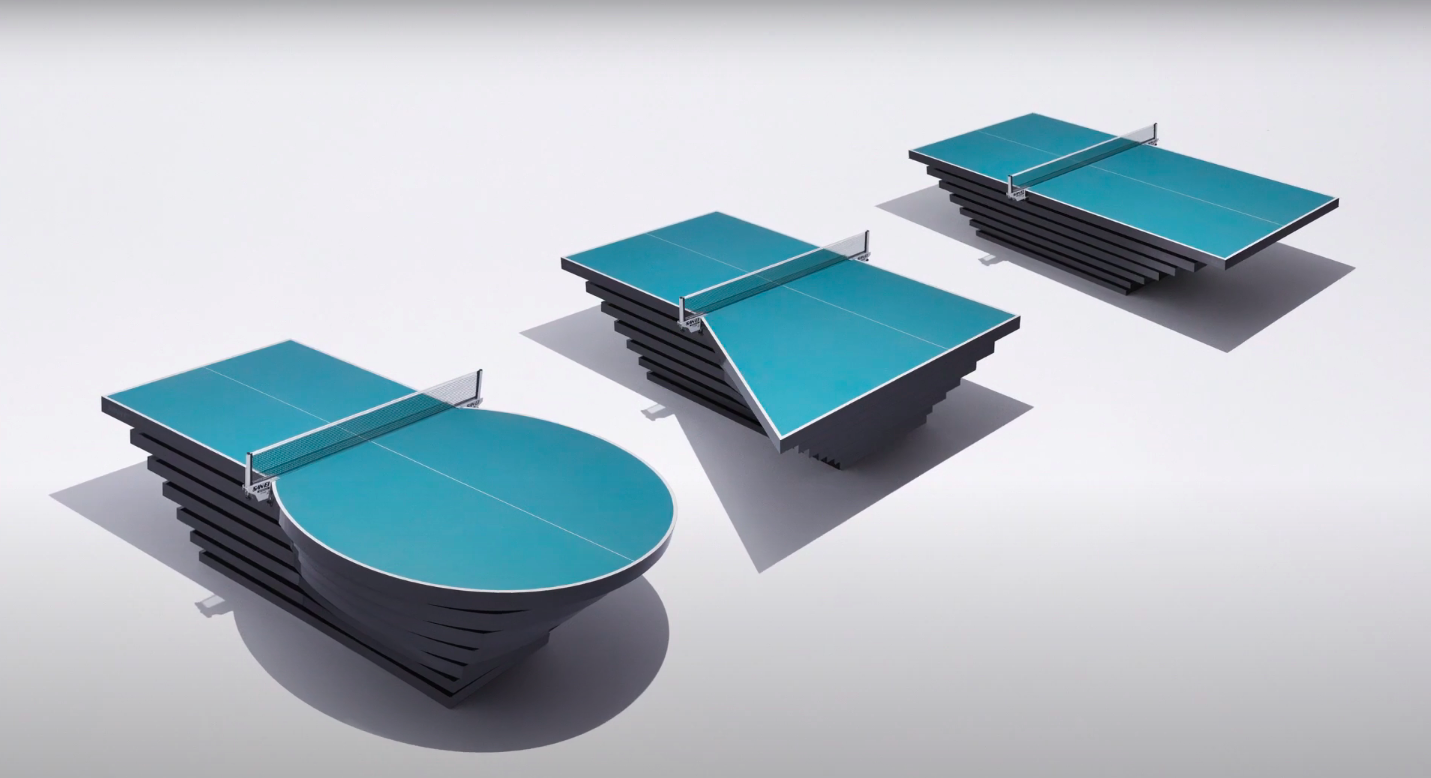

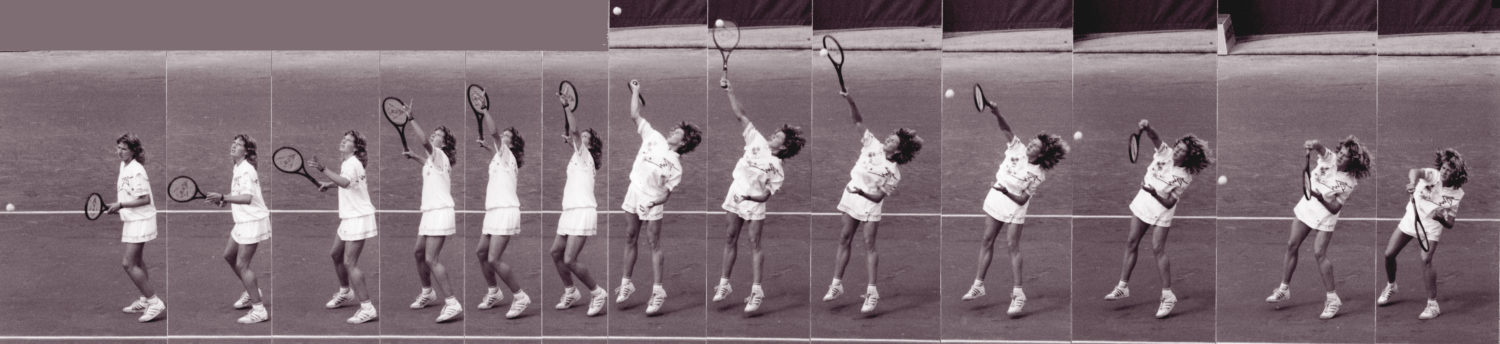

So, what is touchtennis? Quite simply, a scaled down adaptation of tennis. It is played on a 12 x 5 metre compact court for singles and 6 metres wide for doubles with foam balls, a foldaway net and 21” tennis racquets, designed for adults and children to play on any surface. Although played with a junior sized racquet and with a smaller net and court than in tennis, any similarities with Mini, Teddy, Short or Junior tennis end there. “It’s not an adaptation of those because none of them involves spin, kick serves, or forehand inside out winners. We are more of a compact form of tennis, or an expanded form of table tennis than we are of any of those others. Tennis that is scaled down in length, distance and timewise so that nobody requires Andy Murray-like movement to experience an amazing rally!”. He winces when I refer to him as an inventor/entrepreneur preferring the word ‘adapter’: “I only adapted what was already a glorious and beautiful game (tennis) and came up with rules and regulations that made it possible for me to be the G.O.A.T at something, it is that simple!”

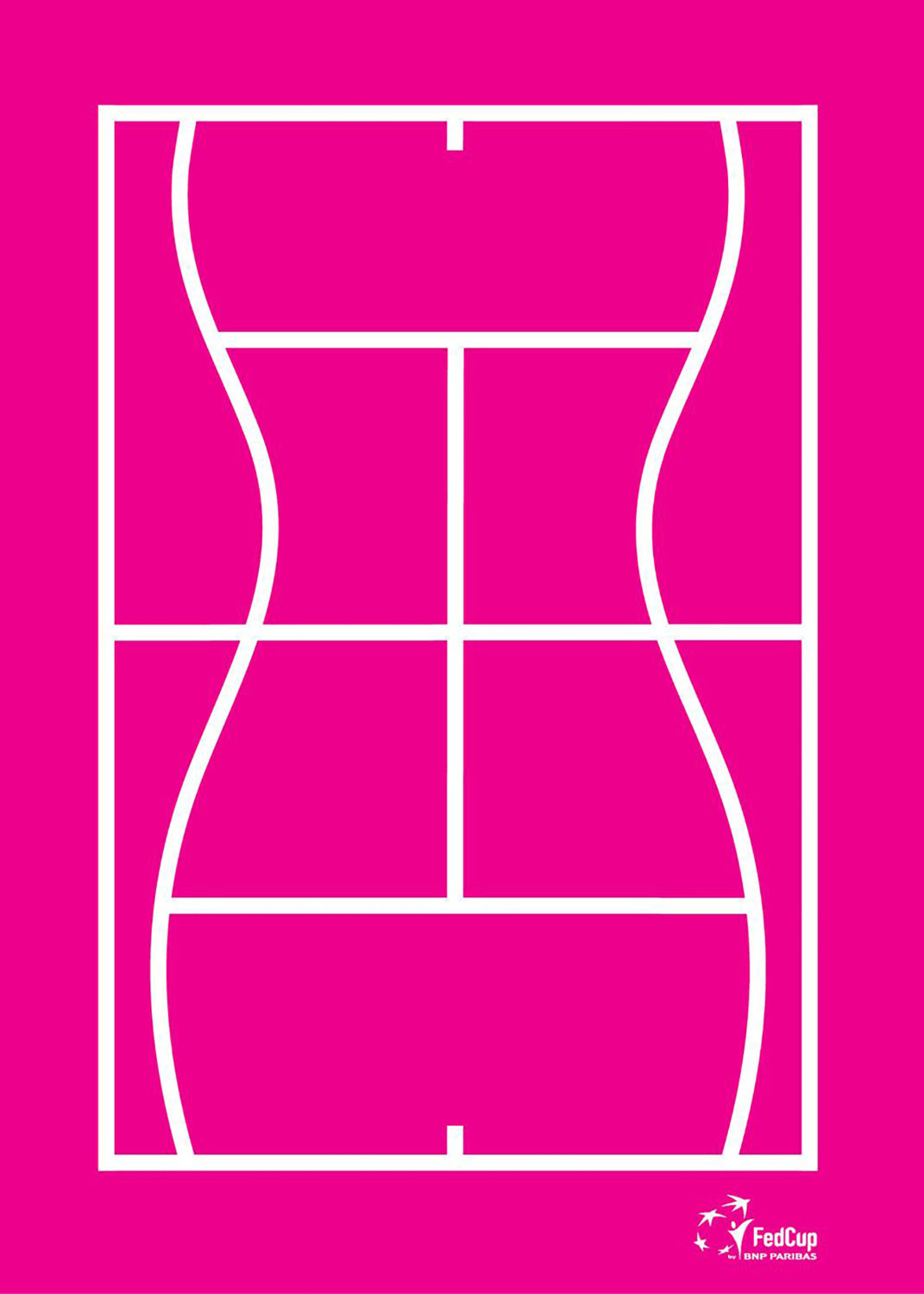

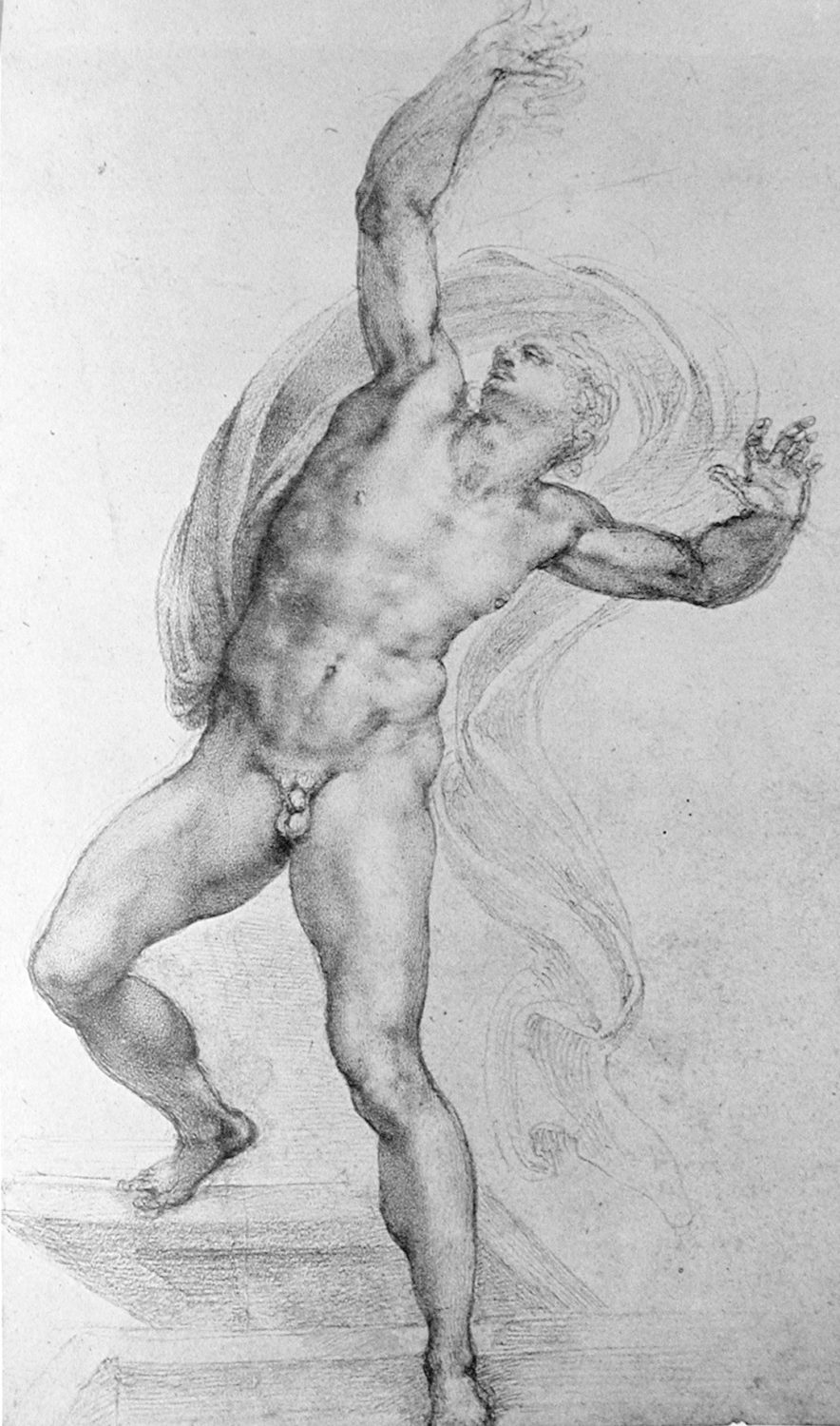

Touchtennis’s matches are shorter than tennis. The official ball is unique, with a higher bounce enabling any age to play. The dense foam has less impact on the body, works in the wind and rain, as well as on bad lawns and different surfaces. Quirky rules enable more drama and fun for both player and spectator: one serve only, ‘sudden death’ at deuce and even permission to hit a shot with a body part, only if the racquet has been thrown to make a shot at an unreachable ball. Its website describes it as “brains over brawn, touch over power, spin over strength, flair over fighting”1. Which is why Ahmad’s brother suggested the name, “because you can never win a point without touch…it is about feel, touch and control. You need more than a booming serve or a beast of a backhand”. The spelling is significant – one-word, lower caps, “capitalising the ‘t’s looks hard and aggressive. So, we soften the way the name appears. I do not think many sports do a good job of attracting women. I’d like touchtennis to be for anybody regardless of age, ethnicity, gender.”

Ahmad decided to start a world champion- ship with friends and family on 2nd December 2007, (now celebrated as World touchtennis Day). By chance, he began working with a local council in Elmbridge allowing him to set up 8 touchtennis courts on a disused bowling green on the condition that he would help the community. The free weekly sessions, including racquets and balls where an overwhelming success, “I realised that it was a little bit bigger than just my back garden and me”. Touchtennis now has a world tour with slams, masters tournaments, a ranking system and cash prizes. There are currently 8 touchtennis licensed countries including Spain and its national tennis federation (the RFET) that are part of the federation. Ahmad sees that growing at a rate of 3 or 4 countries a year, eventually existing in 60 or 70 countries.

We discuss touchtennis’ positioning alongside two other modern popular racquet sports, Padel and Pickleball. “I can see touchtennis being played with a much greater participation level. Look at futsal (football scaled down), and the greats that have gone from playing futsal to winning in world cup football: Maradona, Ronaldo, Ronaldinho. They developed more feel, touch, and control from playing on a smaller pitch. And on the streets of Brazil, I can see touchtennis being integrated easily, but not Padel. The £35,000 cost of building a Padel court could feed every family in a favela for a year! Alternatively, people can play in the streets with a $2 foam ball, using home-made bamboo racquets. Which one do you think will be played by more people? I would say touchtennis. I am not criticising Padel and Pickleball, but they are only for a certain section of society. Padel’s bats are heavier, its volleys and groundstrokes different. Pickleball is only a doubles game, but if you tried to play singles it is better suited to the exceptionally athletic given a larger court coverage and very low-bouncing ball. Also, these can ruin your tennis, just like squash. Tennis players say they never play squash because it ruins their game. And squash players say they never play tennis for the same reason. Padel is squash with a net!”

“Touchtennis doesn’t require a pedigree or high cost like tennis to start playing”. Ahmad has seen fans making their own touchtennis courts using chairs, string, and chalk to mark out lines. “All I ever really wanted to be a part of was a worldwide community without the rigours, the seriousness, the formalities, or traditions of tennis”. Ahmad is confident that touchtennis can only improve one’s tennis game. “If you scale everything down, it will make your hands faster, so you need to put more spin on the ball when you play touchtennis. It is going to help you to control that ball in a small space. So as soon as you get out on a full-size court you feel like you can’t miss.”

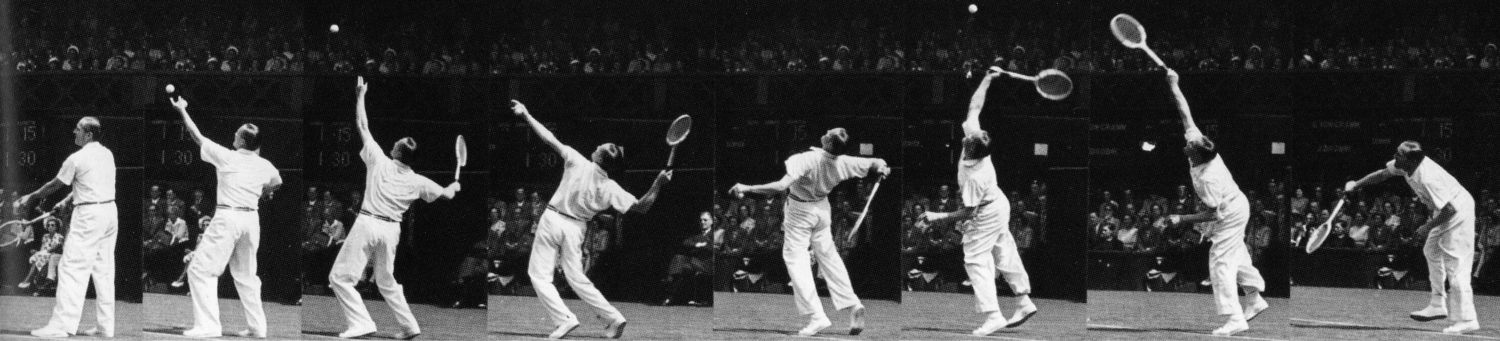

There is an impressive celebrity following, both from the world of professional tennis (Fernando Gonzales, Nicolás Almagro, Tracy Austin, Dan Evans, Chris Eaton, Emily Webley- Smith, 5-time touchtennis slam winner Marcus Willis), comedian Miranda Hart and world-famous adventurer, Bear Grylls. It is easy to see how touchtennis could continue to attract tennis players. Ahmad’s historical tennis knowledge is impressive as we discuss the 1990s – a period that he loves (and I do too). “I’d like to play touchtennis against Fabrice Santoro or David Ferrer. Ferrer’s intensity and inside out forehand would be a joke! It would be impossible to get the ball to his backhand on a compact court, and Fabrice Santoro because of his hands. I would also have loved to play the late Jana Novotna for her serve and volley, and Monica Seles, who I consider as the purest ball striker in the history of tennis. Have you ever seen anyone hit the ball as cleanly and flatly in the corners as she did, hitting winners up the line, returning a Steffi Graf slice?”

I ask if he intentionally injected touchtennis with the same drama of that era, somewhat lacking in today’s tennis. “Absolutely it was intentional. When players like Marcus Willis and Chris Eaton started playing touchtennis, they won points with massive first and second power serves, which was dull. I wanted the ‘cat and mouse’ of that era and the Sampras-Agassi matches, my favourite matches ever! I love the third set of the Wimbledon match between Graf and Sanchez Vicario in 1996. In a 20-minute game, Steffi was forced to hit topspin and volley because she was not going to beat Vicario from the baseline that day.”

Ahmad’s vision to democratise touchtennis is clear. A sport to be played anywhere, everywhere, and for everyone. Watch some touchtennis matches online, and it is difficult not to be carried away with the emotion and drama. “You see people losing and laughing, going home with a smile on their face… I just want to have a world tour of barbeques where touchtennis is also being played while these barbeques are going on”. Ahmad’s repeated use of the words ‘tribe’ and ‘community’ underpin this. Fun rather than money is the focus. Any profits are reinvested or donated to charity.

Bear Grylls once commented on Twitter that touchtennis is “the best cardio workout but allows you to play like a hero”. I ask Ahmad what my chances are of becoming “the Serena Williams of touchtennis”. “Absolutely, 100%, I’ve no doubt you could. Because the ball is so forgiving. I’ve shown this example to so many people, many times.”

I compare him to the inventor of lawn tennis, Major Walter Clopton Wingfield. Like Ahmad, Wingfield invented a portable tennis kit. His contained a net and posts, four racquets, a mallet and a line brush accompanied by a book of rules. He likes this comparison, particularly as neither came from a sporting background. But he is quick to point out the difference: “I’m not selling to Lords and Ladies that have got 50-acre gardens, but to people in council estates, not hunting estates, so my kits are affordable. And if lockdown has taught us anything, it is that touchtennis can be played anywhere”. Without hesitation he adds, “the major difference is that I would have beaten him”. Of course, I wouldn’t expect any less from the G.O.A.T. Will Rashid Ahmad have as much impact on the world as Major Wingfield? They do say that history repeats itself.

Story published in Courts no. 1, summer 2021.