THE

Supercoach

“Agassi,

Seles,

Courier,

Tommy Haas,

Kournikova,

Sharapova,

my Serena,

my Venus –

come on

let’s keep going,

baby”.

Nick Bollettieri, 2017

The Supercoach is a term that has entered tennis parlance in the last decade or so. It was coined to describe former pros returning to the tour to lend their wisdom, guile, and experience to top-ranked players who wanted to, either, unlock their potential or add new components to their game. Agassi, Lendl, Becker, Edberg, Ivanisevic, and McEnroe have each returned as Supercoaches with different levels of success and visibility helping the likes of Djokovic, Murray, Federer, Zverev, and Raonic.

There is also another breed of a Supercoach, mentors who have never won a serious tennis match in their lives but possess other qualities that have led them to have golden coaching careers and legacies.

In the last decade, we have seen, for example, the emergence of a Frenchman who, in fact, audaciously calls himself The Coach – no doubt pronounced THE Coach – Monsieur Patrick Mouratoglou. THE Coach (or perhaps LE Coach) has been by Serena Williams’s side since 2012 and, as her career enters the twilight years, he can also be seen courtside with his new charges: Stefanos Tsitsipas and Coco Gauff. His success enabled him to move his modest tennis academy in a Paris suburb to a stunning, state-of-the-art facility on the French Riviera, together with a separate 5-star hotel for the weekend warriors, and even outposts in Dubai and Greece (coming soon, apparently). Not one to shy away from media attention, he also finds time as THE Coach to provide his expert opinion, in front of the camera, of course, on Eurosport. If you’re an upcoming talent, it’s the eye of Mouratoglou that you want to catch, and for a good reason.

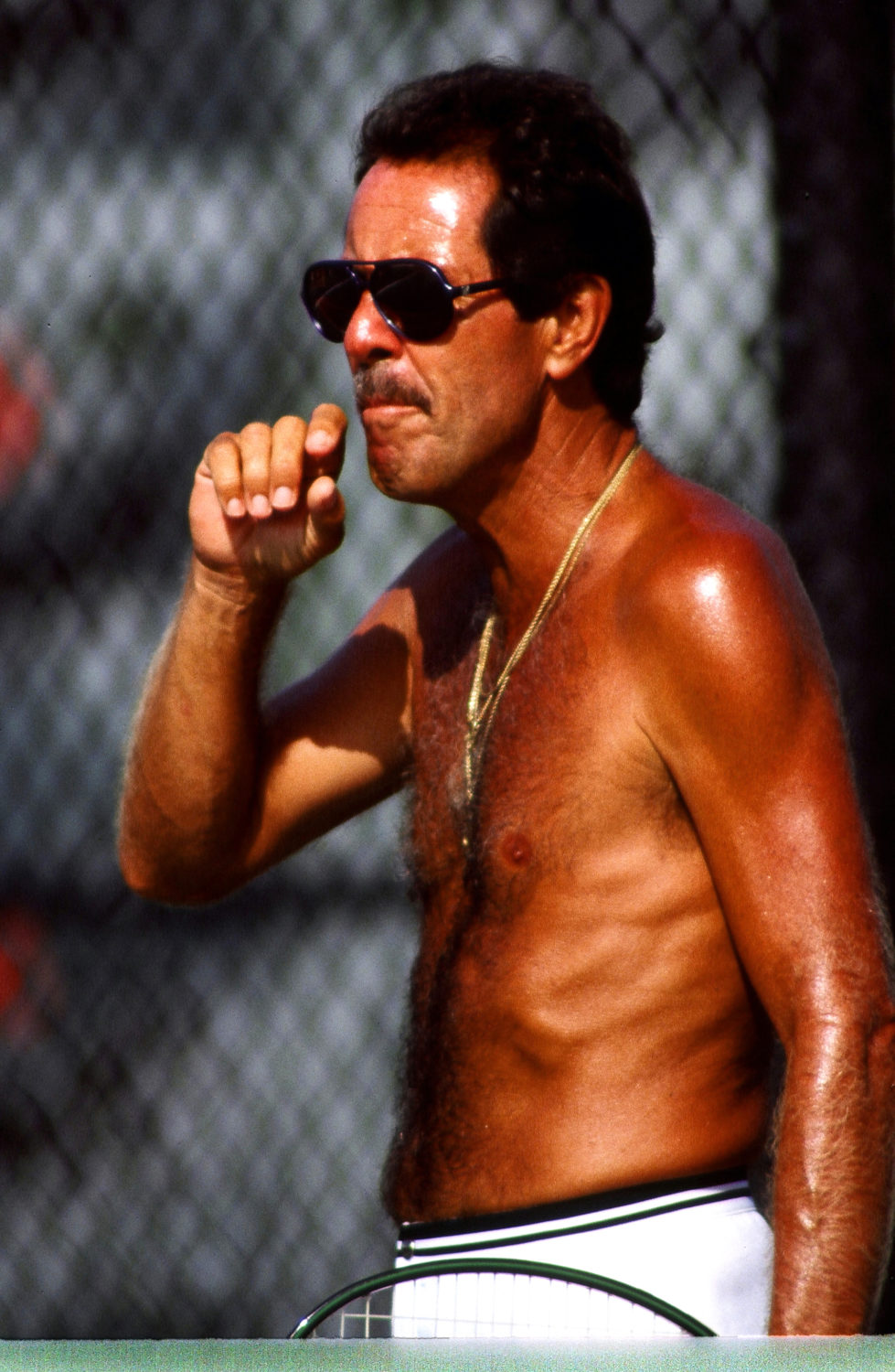

In Florida, however, there is a 90-year-old man with a perma-tan whose coaching career really does make him THE Supercoach. In Mafioso tennis coaching terms, he’s the Boss Of All Bosses.

If you talk about “Nick” in the tennis circles, people know who you’re talking about. If you talk about his academy in Bradenton, you refer to it as “Bollettieri’s”, even though IMG bought the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy in 1987, and renamed it to the IMG Academy. Nick Bollettieri is more than just a brand, he’s a living legend in the true sense of the word. He might even tell you that himself.

His is a remarkable story fuelled by drive, ambition, and discipline, but also by a bit of good luck as is often the case with pioneers. His military service in an elite U.S. paratrooper regiment undoubtedly formed some of the discipline associated with him. The bit of good luck came when, after dropping out of law school in Miami in the mid-1950s, he found himself coaching tennis in its Golden Era of the 1970s and 80s – a time when tennis had just turned professional and inevitably went global. Everyone wanted to play tennis back then.

Nick never aspired to be involved in tennis, but he fell into coaching, and has never left it. Until the mid-70s, he held unremarkable coaching jobs across the U.S. and in Puerto Rico until an opportunity popped up in 1976 to coach on Florida’s Gulf coast at the Colony Beach & Tennis Resort on Longboat Key. The Colony has since gained notoriety for the long-running litigation between its condo-owning residents and the resort’s landlord, and now sits empty, derelict, and awaiting redevelopment. But in 1976, it was the go-to, dreamy beach resort with tennis courts, surf, and the best of Florida-living. Well-heeled tennis-playing families on vacation would see Nick in action, coaching among the palm trees, sporting a copper tan that has since stained his skin permanently, dressed head-to-toe in Ellesse. So far, nothing unusual for the late 70s.

As Nick tells the story, it was at that time that he started to think about setting up his own club, and a chance encounter gave him a unique idea. One afternoon, while coaching a teenager on vacation at the Colony, she made a jokey comment that her father would like her to move in with Nick rather than go home with her family – such was the tremendous impression Nick’s coaching had made. And in that girl’s comment was the birth of Nick’s idea – the tennis boarding school. That girl was Carling Bassett who, after a few years of Nick’s coaching, became ranked number eight in the world.

It didn’t take long for Nick’s idea to turn into an improvised reality, with 15 or so talented kids taking part in a junior programme, sleeping in bunk beds at Nick’s home and the homes of other pros from the Colony. At the time, those kids included not only Carling, but Jimmy Arias, Aaron Krickstein, Kathy Horvath, and Anne White. All of them turned pro, and each with a palmarès that includes Grand Slam appearances. Soon enough, the kids were occupying every corner of their coaches’ homes, the stress of which cost Nick his marriage. A converted motel housed some of them for a while, but as the reputation of Nick’s live-in programme grew, the number of kids he was taking on increased. Suddenly, the junior coaching programme was monopolising all of the courts at the Colony, much to its guests and residents’ irritation. It was time for a move.

It wasn’t long therefore before the all new Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy, or “Bollettieri’s” as it came to be known, opened its doors in Bradenton in 1981, occupying a 12-acre site, financed pretty much entirely by the father of two of Nick’s juniors who saw the potential in, what we now call, a tennis academy. Back then, this was still a novel concept, but the idea was soon imitated, and still is today – from Saddlebrook in Florida which emerged soon after to Nadal’s academy in Mallorca being the latest of the many academies now spread across the world. The idea was simple: you handed your precociously talented kid over to Nick and his team. Then, they housed them, fed them, sent them in the morning to the local high school on hired buses, and then drilled tennis into them for the rest of the time, so that they ate, slept, and breathed it. Practice makes permanent, as the saying goes in tennis. At the start, the kids would also do chores around the site and string racquets, a leftover requirement from the days at Nick’s home where they had to earn their keep.

The fly in the ointment was money. To build his brand, Nick realised that he needed to take in the very best in junior talent. The trouble was that the families of most of those kids were not the well-heeled “Colony types”. To get around that, Nick gave scholarships to dozens of kids, wheeling and dealing commercially on the side as best as he could in order to prop up the overheads. Alas, with no great success. In fact, the sale to IMG in 1987 was to keep the NBTA from going under financially, about which, to his credit, Nick has been candid in interviews over the years.

The success of Nick’s coaching techniques in the early 80s soon put the NBTA boot camp squarely on the tennis map. By then, Bollettieri’s was producing its own new way of playing the game. The new oversized racquets, developed by Howard Head at Prince, provided a larger sweet spot, which in turn created more margin for error for powerful baseline hitting. Nick had also spotted that one of his players, Jimmy Arias, was holding his racquet differently for his forehand, in what we now call a semi-western grip. Jimmy’s grip enabled him to hit heavy forehands with increased topspin so that balls would stay inside the baseline despite the racquet head speed Jimmy was generating. Everyone else was still using a continental grip on the forehand. The combination of the Prince racquet and the Arias grip gave birth to the “Bollettieri forehand”, a weaponised stroke which completely changed how the game was played. All of Nick’s kids had big, terrorising forehands.

This is where things started to get really interesting for Nick, and when the NBTA’s heyday started. He had kids turning pro, hitting the fuzz off the ball with giant groundstrokes, and pulverising opponents from the baseline. That was the brand of tennis he was pushing – power baseline tennis. Look at the list of names in the quote at the start – all power baseliners, and early prototypes of Djokovic, Zverev, Medvedev, and Murray.

The other brand that Nick was pushing was Nick himself. The omnipresent coach on TV wearing NBTA-branded Nike and Adidas clothes is what the world saw. Behind the scenes though, those within the inner circle or at Bollettieri’s have given differing accounts of what he was like and of the student life at Bollettieri’s.

There is the Nick described as the father figure, one who would do anything to support the kids under his stewardship, who worked night and day to keep the lights on at the academy, always supportive and positive, the ultimate mentor to have on your side, with some tough love but love nonetheless, handing out scholarships willy-nilly, and spending hours patiently on the phone to parents.

Then there is the other Nick you hear about. Egocentric, dictatorial, the ex-paratrooper turned warden of his home-made prison camp, always looking for the side hustle, showing overt favouritism for his wards who were all competing for his attention (just ask Jim Courier) – a breeding ground for a type of tennis Stockholm Syndrome, money mismanagement, ruthlessness, and one-dimensional tennis.

No doubt, there is some truth to both accounts. History shows us that, even in tennis, you can’t reach the highest peaks without being utterly driven and selfish – so said Pete Sampras about his own journey. Ultimately, Bollettieri’s wasn’t like an Ivy League college with hundreds of years of prowess behind its reputation that it could ride on – it was about Nick and Nick only. He was its brains, its heart, and its face, and with all that, tough decisions came along the way.

If you believe in what he has said, Nick had no tougher decision to make, and no greater regret, than his split with his most prodigious and famous home-grown talent, Andre Agassi. Many chapters in many books have been written about that. Nick has even spoken about it, with genuine sadness, in the 2017 HBO documentary about his life, Love Means Zero, in which he speaks to the camera with unnerving directness. The fallout with Agassi seems to have been a disagreement – perhaps about money, perhaps Nick jumping before he was pushed, done by letter, done by fax, Agassi heartbroken, they’ve barely spoken since, they’ve reconciled recently – who, other than the two of them, really knows what happened, and even then there’ll be two sides to that, too.

But whatever happened, Nick and Andre together formed an iconic partnership in tennis. It immediately brings to mind images of denim and neon Lycra clothing, Prince and Donnay racquets, the Nike Air Trainer 1, the Agassi hair and his groundstrokes, the Bollettieri tan, his Oakley sunglasses, shirtless practice sessions in Florida. And, of course, Agassi’s win at Wimbledon in 1992, with Nick in his players’ box visibly consumed with pride.

The list of players Nick has helped at some point in their pro careers is much longer than is publicly known. Some were, of course, home-grown at the NBTA from their junior days, but many went to Bollettieri’s for rehab from injury, or for a slice of Nick’s expertise, maybe without their coaching team knowing too much about it, or for a training block, or for an equipment change. There are even photos and footage on YouTube of Björn Borg in an NBTA t-shirt practising in the early 1990s at Bradenton with a stack of Boris Becker’s racquets. Becker himself has been at Bollettieri’s for periods of time, as have Mary Pierce, Mark Knowles, home-grown David Wheaton, Marcelo Ríos (who Nick describes as the most talented ball striker he has ever seen), Petr Korda, Jelena Janković, and Xavier Malisse – on and on the list goes, and that’s before you even consider the players currently on tour.

Is Nick done now that he’s 90? Nope. Take a look at his Instagram account. Is he still sun-bronzed? Yep. Take another look at his Instagram account. And is he The World’s Best Supercoach Of All Time?

You’d better believe it, baby.

Story published in Courts no. 2, autumn 2021.