The Queen said

“it must have been terribly hot”

on Centre Court.

Did you know that Althea Gibson was in a John Ford movie playing opposite John Wayne and William Holden? Are you old enough to know who Althea Gibson was?

And why is it that, although she had a major role in the 1958 movie, Gibson’s billing hardly ever showed up in any publicity? She had, after all, been ranked world number one female tennis player one year earlier. In 1956, she had won the French Open, and in 1957 she had glided to the top with victories at the Australian Open, Wimbledon, and the US Open. Is it because she was thought of more as a sportsperson than an actress that, even though she was on screen more than any other woman except for Constance Tower, her name is twenty-third in the credits?

More likely, of course, the reason that the 5ft 11in tall 32-year-old who played a slave girl in Ford’s film was not given star billing, or any billing at all, is that she was Black.

When she won at Roland Garros, she had been the first Black woman ever to win a Grand Slam tennis title. Six years earlier, in 1950, she had, at age twenty-three, broken the colour barrier of the American Lawn Tennis League by playing at the exclusive West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills in the U.S. National Tennis Championships. In 1951, she had been the first African-American player to play at Wimbledon. None of it had come easily. Following her Wimbledon title six years after that, when she was shown being congratulated by Queen Elizabeth, she said, “Shaking hands with the Queen of England was a long way from being forced to sit in the coloured section of the bus going into downtown Wilmington, North Carolina.”

Gibson was born to sharecroppers who worked on a cotton farm in rural South Carolina. The Great Depression had an immediate impact on rural farmers, and in 1930, her parents moved to Harlem. The Police Athletic League operated a play-area near to the family’s apartment on 143rd Street between Lenox and Seventh Avenues—Gibson, a natural athlete, played lots of sports there, and by age twelve, she was the women’s paddle tennis champion for all of New York City. Her father taught her boxing, and she took to it naturally. Her neighbours made a collection for her to have tennis lessons. At first, she considered tennis to be a sport for weak people. She would later say that combat came so naturally to her that she would “fight the other player every time I started to lose a match,” but, still, she played and she played well.

Soon, Gibson began to win tournaments. She was discovered by Walter Johnson, a physician in Lynchburg, Virginia, who mentored young African-American tennis players—Johnson would eventually mentor Arthur Ashe as he did Gibson—and he helped her gain entry into tournaments that did not normally have Black competitors. She moved back to the South, to Wilmington, North Carolina, and her tennis was of such sterling quality that she got a full athletic scholarship to attend Florida A&M University.

But the tennis world was not fully open to her. Gibson was initially kept out of the US National Tennis Championships at Forest Hills. Racial discrimination was prohibited by law, but to qualify for the Nationals, players had to win a certain number of sanctioned tournaments, and they were held at all-white private clubs where Blacks never went onto the courts, even in tournaments technically open to everyone. It took the doyenne of women’s tennis, Alice Marble, to publish an editorial in the July 1950 issue of the magazine American Lawn Tennis to change history.

Gibson reprints Marble’s diatribe in her lovely autobiography, I Always Wanted to be Somebody— a book that is rare for its candour, lack of boasting, and its freshness of tone, even if it is not great literature. Marble, as cited in Gibson’s book, writes that lots of people “Want to know if Althea Gibson will not be permitted to play in the Nationals this year. Not being privy to the sentiments of the U.S.L.T.A., … when I directed the question to a committee member of long standing, his answer, tacitly given, was in the negative … The attitude of the committee will be that Miss Gibson has not sufficiently proven herself.”

Marble writes that the committee member did not think it adequate that Gibson had been a finalist in the National Indoors. She would have to play in the tournaments in Orange, East Hampton, and Essex. But they were invitationals. “If she is not invited to participate in them, as my committee member freely predicted, then she obviously will be unable to prove anything at all, and it will be the reluctant duty of the committee to reject her entry at Forest Hills.1

“We can accept the evasions, ignore the fact that no one will be honest enough to shoulder the responsibility for Althea Gibson’s possible exclusion from the Nationals. We can just ‘not think about it.’ Or we can face the issue squarely and honestly … It so happens that I tan very easily in the summer—but I doubt that anyone ever questioned my right to play in the Nationals because of it.”

Just after the editorial appeared, Gibson tried to enter the New Jersey State Championships at the Maplewood Country Club, but was refused on the basis that there was “not enough information.” Then, however, American Tennis Association officials joined the battle for Gibson’s admission to Forest Hills, and the Orange Lawn Tennis Club in South Orange, New Jersey, allowed her to play in an important championship. “The dam broke,” Gibson would write. At age twenty-three, she was invited into the Nationals and became the first Black player, female or male, to enter the tournament. An article in The Daily Worker reported that “No Negro player, man or woman, has ever set foot on one of these courts. In many ways, it is even a tougher personal Jim Crow-busting assignment than was Jackie Robinson’s when he first stepped out of the Brooklyn Dodgers dugout.”2 Ebbets Field, where the Dodgers played, did not, after all, reek of exclusivity. The half-timbered Tudor-style buildings of the elegant club in Forest Hills, an oasis of verdure and space in New York’s borough of Queens that seemed like an English village in the middle of the metropolis, made it a bastion of America’s white Protestant establishment. It’s thirty-five tennis courts bespoke quiet wealth—that was one large piece of real estate a short trip from midtown Manhattan. The founders and subsequent inner sanctum of the place had ideas on how to keep it the way they wanted; like private schools, dancing classes, country clubs, and universities all over America’s so-called segregated Northeast in the 1950s, there were unwritten rules concerning the eligibility of Blacks and Jews.

Gibson’s getting into the tournament was a breakthrough, but it would not have secured her membership in the tennis club. In 1959, Ralph Bunche Jr, the fifteen-year-old son of Dr Ralph Bunche—one of the most distinguished Black people in America, a Nobel Prize winner and United Nations Under-Secretary for Special Political Affairs—was denied membership. Bunche Jr was taking lessons with George Agutter, a 72-year-old pro who had been teaching at Forest Hills for 45 years, and Agutter had urged him to apply for junior membership. Agutter had not realized that his pupil was a light-skinned Negro. After the error was recognised and Bunche Jr was told it was out of the question, “The elder Bunche thereupon called the club president, Wilfred Burglund, who said he was sorry, but Forest Hills simply didn’t take in Negroes or Jews. When Bunche protested that Negro star Althea Gibson twice won the women’s singles title at Forest Hills (in 1957 and 1958) Burglund replied that the club had no control over the players in the tournaments held there by the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association, but it definitely could decide its own membership. If the club admitted Negroes, said Burglund according to Bunche, hundreds of its members would instantly resign.3

Bunche went public about the matter, which was rare for him. “Neither I nor my son regard it as a hardship or humiliation. It is not, of course, in the category of … segregation … suffered by … Negroes in the North as well as the South. But it flows from the same well of racial and religious bigotry. Rather, it is a discredit to the club itself.” Five US senators publicly spoke up against the Club’s policy, and New York’s deputy mayor joined the protest against the heinous policy. The response from the leadership of the Club was silence. The US Supreme Court had made its landmark school integration decision five years earlier, but since the club had nothing in its bylaws or constitution establishing the policy that prohibited Blacks and Jews and other unspecified minorities from joining, no one had further recourse, and the policy stayed in place. Even with the breakthrough allowance to play at Forest Hills, it was not all onwards and upwards. Gibson would write that she was “discriminated against by the tournament committee when they assigned me to Court 14, which is the farthest removed from the clubhouse of all the courts on the club grounds and has the smallest capacity for accommodating spectators.”4

Ginger Rogers, who played mixed doubles in the tournament, was, on the other hand, put on the court directly in front of the clubhouse. Even at her obscure location, though, Gibson was noticed, to the extent that she had to cope with the annoyance of flashbulbs constantly going off in her face and temporarily blinding her. The press was excited by her breakthrough presence, and her tennis was remarkable. Lean and muscular, she used her long arms gracefully, dazzling people especially with her powerful serve.

Whatever the battles she had been through to get her into Grand Slam tournaments, in 1957, not only was Gibson the first Black champion at Wimbledon, she was the first champion ever to receive the trophy personally from Queen Elizabeth II. When she had been getting ready for the match, “Everyone in the dressing room was talking excitedly about the news that the Queen was going to be there. That made me feel extra good. I would have been terribly disappointed if she hadn’t been.”5 An hour before the match, when she was practising on a side court, she “saw Queen Elizabeth eating lunch on the clubhouse porch. Instead of making me nervous, it made me feel more eager than ever to get out there and play.” As Gibson changed into a fresh shirt, she was counselled how to curtsy to the Queen after the match. Then, just after Gibson won the finals with dashing tennis, the tournament officials asked her and the other finalist, Darlene Hard, to walk over to the umpire’s chair and wait as workmen unrolled a red carpet from the royal box.

“Queen Elizabeth, followed by three attendants, walked gracefully out on the court. She wore a pretty pink dress, a white hat and white gloves, and she was absolutely immaculate, even in all that heat. One of the officials called me to step forward and accept my award. I walked up to the Queen, made a deep curtsy, and shook the hand she held out to me. ‘My congratulations,’ she said, ‘it must have been terribly hot out there.’ I said, ‘Yes, your majesty, but I hope it wasn’t as hot in your box. At least I was able to stir up a breeze.’ The Queen had a wonderful speaking voice and looked exactly as a Queen ought to look, except more beautiful than you would expect any real-life queen to look.” Queen Elizabeth then presented the gold salver to Gibson. Gibson “curtsied again and backed away from her… I remembered the backing away business from the movies.6 The Queen then retreated and the red carpet was rolled back up.

At a celebration ball that evening at the Dorchester Hotel, Gibson addressed the Duke of Devonshire, who was master of ceremonies, and said, “In the words of your distinguished Mr. Churchill, this is my finest hour.” She thanked “the many good people in England and around the world whose written and spoken expressions of encouragement, faith, and hope I have tried to justify.” She said that her win was “a total victory of many nations… created through the international language of tennis.”7 Then Gibson started the dancing by going out on the dance floor with the tennis pro Lew Hoad. The two of them circled the ballroom to the song ‘April Showers’, which Gibson had requested, and it took several minutes before others in the awestruck crowd followed them onto the dance floor. In New York, following her triumph in London, Gibson was the second African-American—Jesse Owens had been the first—to be honoured with a ticker tape parade. President Dwight Eisenhower wrote her, “Recognizing the odds you faced, we have applauded your courage, persistence, and application. Certainly it is not easy for anyone to stand in the centre court at Wimbledon and, in the glare of world publicity, and under the critical gaze of thousands of spectators, do his or her very best. You met the challenge superbly.”8

Gibson then won the US Open in the stadium where she had previously been forbidden entry. The following year, she glided to victory yet again in both tournaments. The Associated Press, in both 1957 and 1958, declared her “Female Athlete of the Year.”

It was an unusual idea of John Ford’s to put Gibson in his movie, The Horse Soldiers, and an odd decision on her part to take the role. On the screen, she is subservient and docile. She generally has a look on her face of wide-eyed astonishment.Although she refused to speak in the dialect that Ford had initially requested, and had great dignity as a tall, well-dressed, and pretty slave, was the antithesis of the warrior she was in real life.

And she is shot dead well before the end of the movie, which generally roars with testosterone and is a general bloodbath. It is not a brilliant part, but she is competent at it.

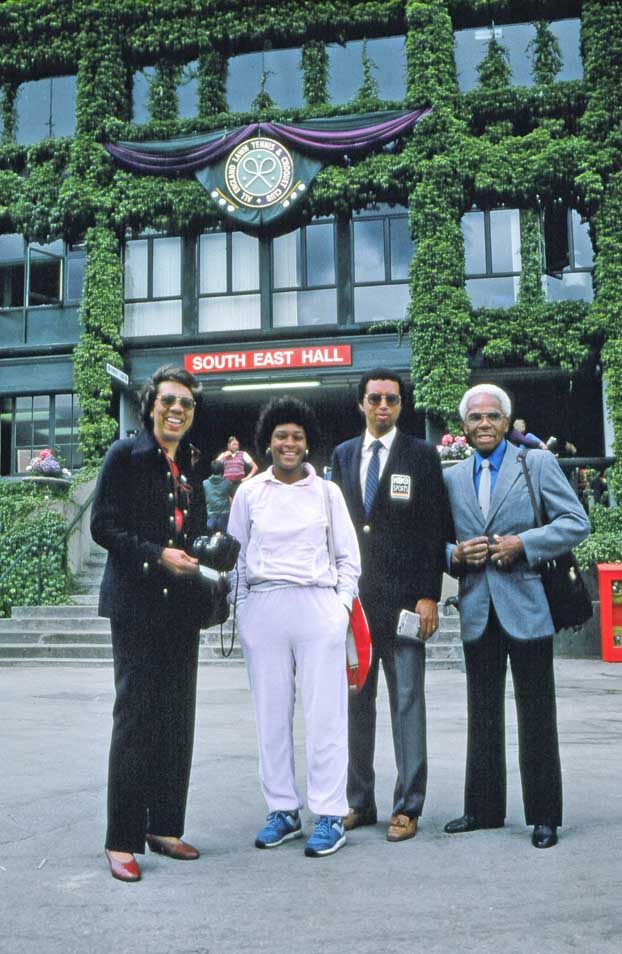

Gibson liked performing, and not just on the tennis court. Gibson was a talented singer and saxophonist; in 1943, she had been runner-up at an amateur contest at Harlem’s renowned Apollo Theater, and in the same year she won those three Slam tennis titles, she had sung in public at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel at an 84th birthday tribute to W.C. Handy, a well-known songwriter who was considered “The Father of the Blues.” The year after she was in The Horse Soldiers, she released a phonograph record and performed on the Ed Sullivan Show. But despite her moments of glory, Gibson struggled. Once she stopped winning Grand Slam matches, she was low on funds, and made money doing exhibition matches before Harlem Globetrotters basketball games. She, and her doubles partner Angela Buxton, who was Jewish, were turned down on the many occasions that they sought admission to the The All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club. Gibson, meanwhile, became a professional golfer, and joined the Ladies Professional Golf Association—the first African-American to do so—at age thirty-seven. She was able to be a member, but still was banned from tournaments not just in the South but also in the North, and often had to dress for matches in her car because she was not allowed into the clubhouse.

The rest of Gibson’s life did not have the glamour of her Queen Elizabeth years. She did well at golf, but not spectacularly, and made money largely by doing sponsorship deals. She continued with golf and tennis, but not on the same level as in earlier years. Nonetheless, in 1976, Althea Gibson became Athletic Commissioner of New Jersey—and was the first woman to hold such a post anywhere in the U.S. Married and divorced twice, she was essentially alone in the world when she then had two cerebral haemorrhages and a stroke and, unable to pay her rent or medical treatment, she asked for help from various tennis organisations but never received it. Fortunately, Angela Buxton raised over a million dollars from mutual acquaintances to ensure her comfort until 2003 when Gibson died. Today, there are children’s books featuring Althea Gibson as an exemplar of courage and tenacity. Through tennis, she changed the world.

1 I Always Wanted to be Somebody, pp. 63-65

2 Rodney, L:

On the Scoreboard: Miss Gibson Plays at Forest Hills, The Daily Worker, August 24, 1950

3 Segregation: West Side Story, anonymous article dated July 20, 1959 in the Ralph Bunche papers of the University of California, UCLA Special Collections

4 p. 71

5 p. 132

6 p. 134

7 p. 138

8 p. 140

Story published in Courts no. 3, Summer 2022.