The Legend of Midtown’s Secret Courts…

Tudor City had fantastic courts a stone’s throw from the UN. But development won… again

A recent New Yorker cartoon — originally published in 2018 and reissued on the website this week — lampooned the situation of the city’s tennis court availability. “The U.S. Open skirts what can seem like the game’s most insurmountable hurdle: getting on a court,” it reads, before surmising how the Grand Slam would fare if professionals had to fend for themselves without Flushing Meadows.

It would be an unending match. The situation may not be as bad as the housing crisis, but the pedestrian tennis player who isn’t a Wall Street banker is getting quickly out-maneuvered all over the city. Courts for which it used to be difficult to get a time, prove nearly impossible. Courts where an eager player could always count on a pick-up game, still mandate signing in and waiting. And those secret courts — the ones that were permitless? Published in the Times’ U.S. Open edition long ago.

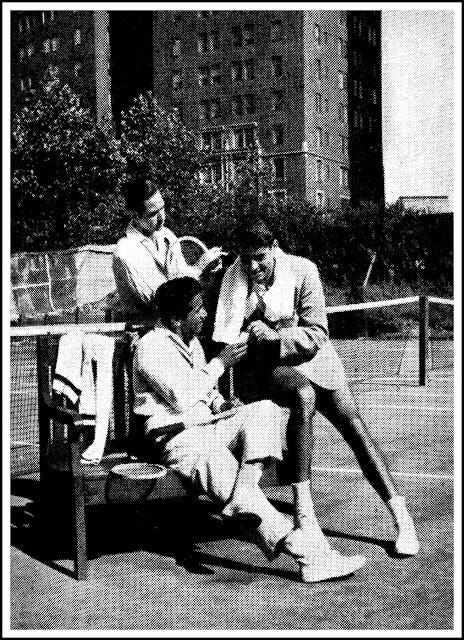

Once upon a time, however, there were fantastic courts in East Midtown, a stone’s throw from Grand Central Station. Bill Tilden played there, as did Jack Kramer and Pancho Segura. Katharine Hepburn would come down from her 49th Street digs and have a match. After his sets, Bobby Riggs would smoke a Chesterfield, which had Riggs under contract at the time, and look cool.

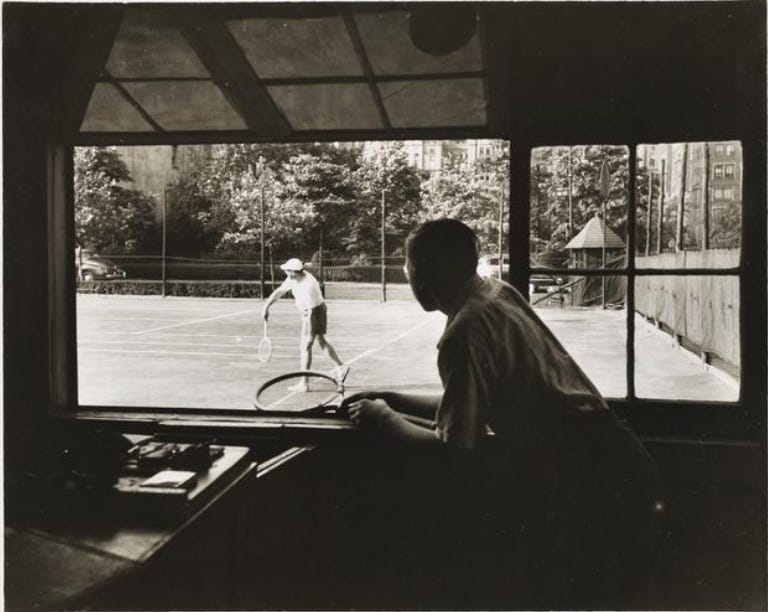

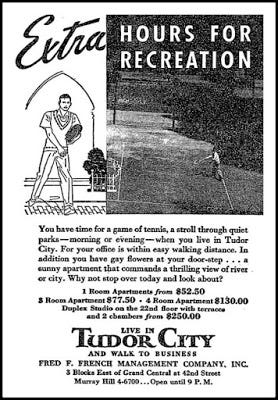

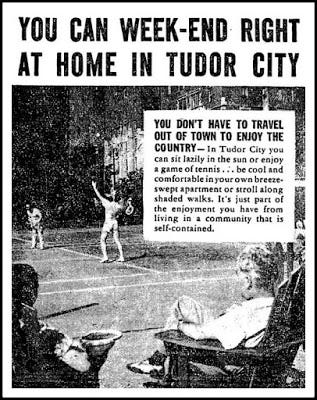

Tennis courts came to Tudor City not by design but by a twist of fate. The Fred F. French Company owned the entire development rising above 42nd Street and 1st Avenue, advertised as a respite from the commuter train to the suburbs. The roaring 20s brought that building boom; the Depression caused a lull. French put the brakes on constructing another edifice of studio and one-bedroom apartments. Instead, he did something communal: he set the land aside for activities, such as concerts, dancing, ice skating and even ski sliding. Tennis stuck.

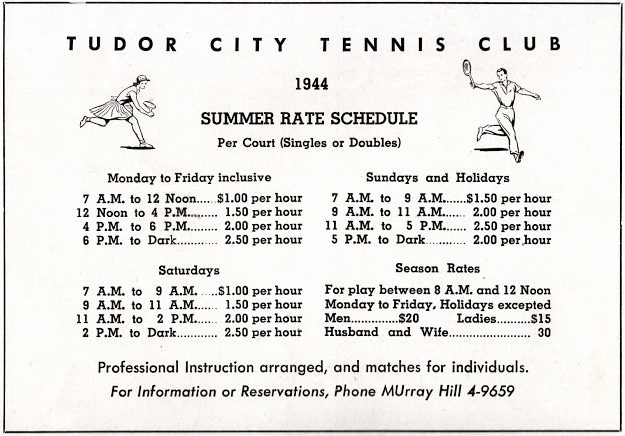

Inaugurated in May 1933, the Tudor City Courts arrived when there were few outdoor courts in Manhattan — and only one indoor (the Heights Casino in Brooklyn). Forest Hills was long opened and Central Park had consolidated into one central location from many random, hand-lined courts, but Tudor City had it all: location, East River views and a place to sun. It was also dirt cheap: about $1 per hour ($14 adjusted for inflation) during off-peak and $2.50 during peak ($34).

The French Company realized the public relations value of the courts — much like Chase bank uses Grand Central as its Squash HQ in January — and promoted them heartily.

Tennis in Tudor City reigned until the post-World War II, when the last holdout of a four-story rowhouse constructed in the 1870s, finally sold, and No. 2 Tudor City Place broke ground in 1954. City dwellers would have to wait another couple of decades to have more available courts. With demand currently at capacity, they are now popping up in the courtyards of buildings with co-ops in the $1 million range (Atelier on the West Side), studios going for $3,000-per-month (River Place in Hell’s Kitchen) and in those nooks and crannies of the city yet undiscovered (Staten Island).