Tennis in the Work of Eadweard Muybridge

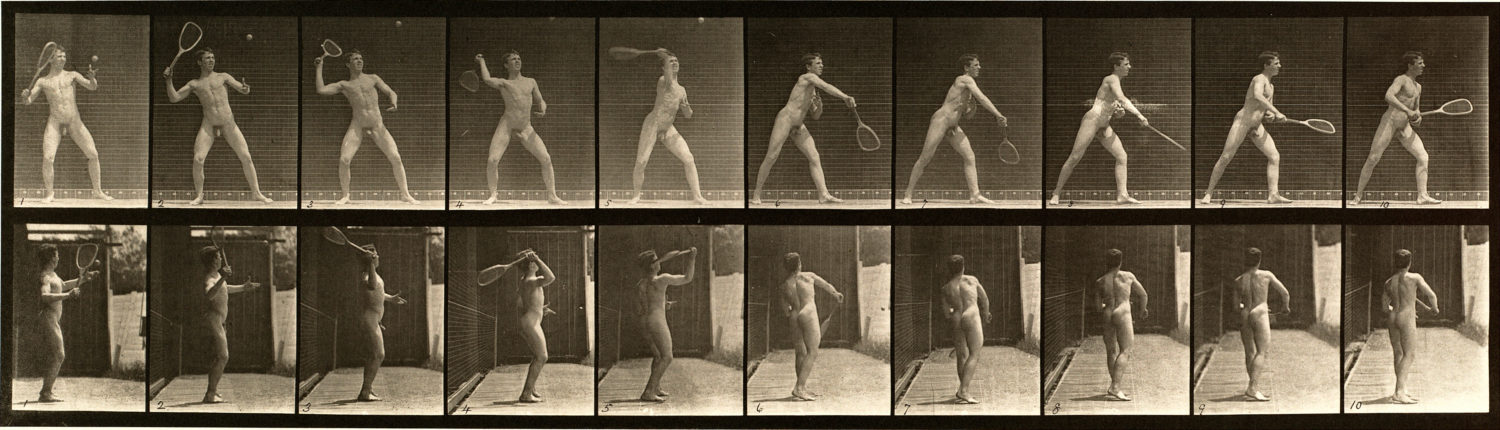

Even before we know who Eadweard Muybridge was, or why he spelled “Edward” that way, or what exactly we are looking at here, and when it was done, the first question is why and how a photographer—in two rows of images, ten per row—made his subject the sequence of movements that constitute the serve in tennis. For many viewers, the second question is why this male tennis player is stark naked, as if it is the most normal thing in the world to have his genitals and thick pubic hair, and the rest of his nude body, in plain view.

It is not so surprising that Muybridge chose the serve as a splendid example of the human body in coordinated motion. He had started his depictions of progressive motion with a horse, in part to show exactly which of the animal’s hooved feet are elevated above the ground, the knees of its lithe legs crooked accordingly, in a correct trot and gallop. Neither had previously been evoked to his patron’s satisfaction in horserace paintings, even those as competent as the wonderful canvases of racetrack scenes and galloping horses by artist like George Stubbs and Édouard Degas.

We have no idea why Muybridge chose this subject, even if we, as tennis aficionados, can appreciate its value. The tennis serve is a fantastic feat. It requires the synchronized action of the players’ weaker arms tossing the ball upwards to the ideal height and position, with an imaginary target, their legs and the body stretched to ultimate height, while the stronger arm, the one that holds the racket, goes first above their shoulders, then down to the small of their backs, and then upwards as if throwing a lance so that the strings and the ball contact that ball that they have tossed as their ammunition. Then players need to hit at the correct trajectory to send the ball over the net and onto a chosen target within the service court, a small rectangle precisely demarcated at a difficult angle across the way. Wanting to dissect specific movements and freeze each element for observation, Muybridge could hardly have picked a better theme.

Yet the naked server is at best an amateur tennis player; his serve weak in a number of ways, among them the most crucial being that he strikes the ball feebly in a position far lower than it should be. Did Muybridge know the sport well enough to recognize this shortcoming?

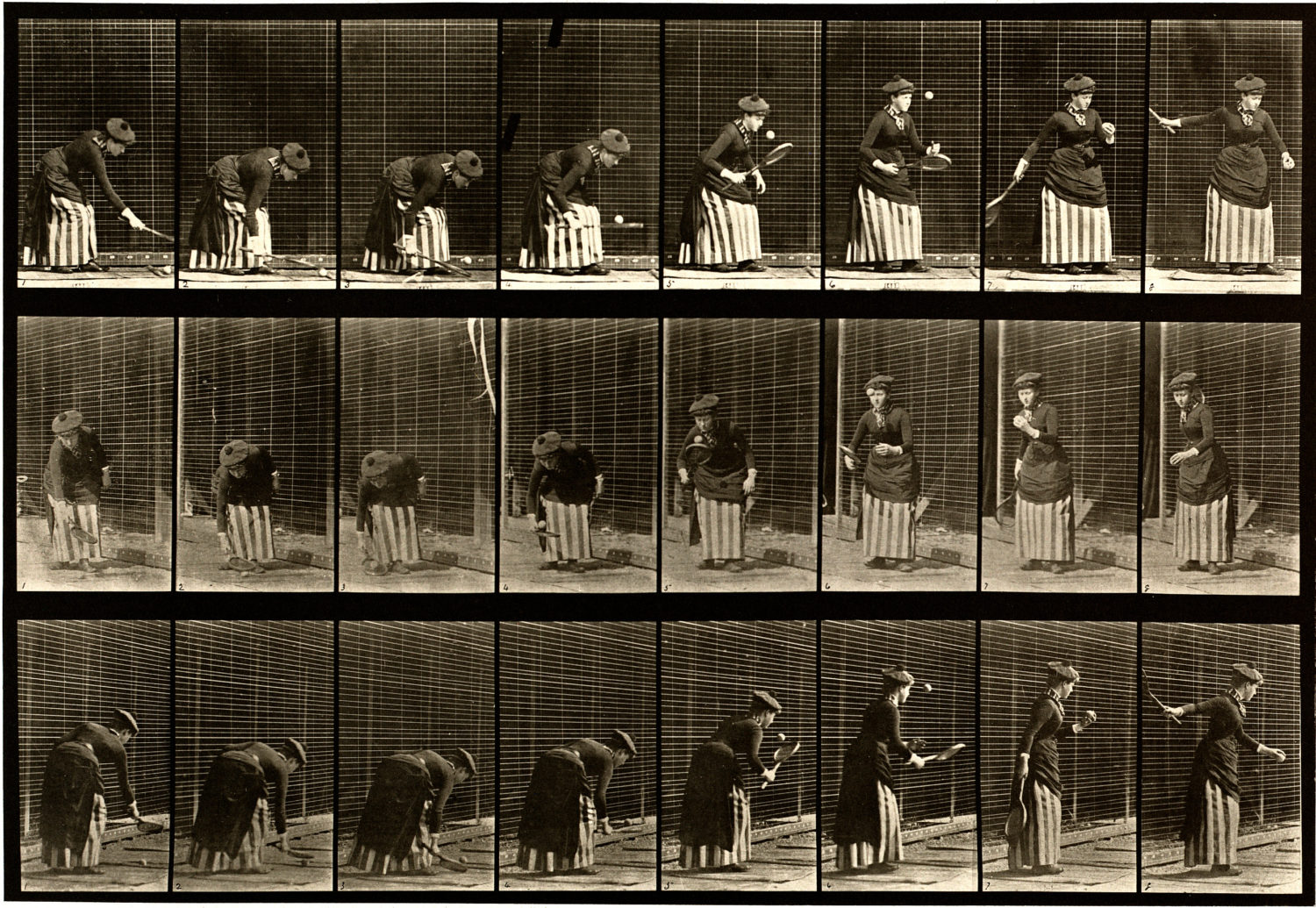

And why is his female tennis player, of whom he did more series than the man, always dressed as primly as Whistler’s Mother? And what is she actually doing in coaxing the ball from the ground only to balance it on the racket face which she holds parallel to the surface of the court?

And who was this photographer whose unusual name had at least six variations, and has now become a familiar reference in the history of camera work with many photography enthusiasts recognizing his work but few really knowing his story? And what was his connection to Étienne-Jules Marey, the French photographer who is the subject of a large plaster bas-relief, replete with the paraphernalia of tennis, at the Roland Garros stadium? Was Marey or Muybridge the first to photograph the body—be in human or animal—in balletic motion?

Muybridge, for sure, was a man of rare inventiveness as well as temerity. When he was born in England in 1830, he was Edward James Muggeridge. Twenty years later, this adventurer who seems more fictional than real—in a novel, his panache would be irresistible—got himself to San Francisco. It was the capital of the Gold Rush in the Wild West, boasting forty bookstores and twelve photography studios. A bookseller initially, Muggeridge started calling himself Helios—the name of the Greek god known as the titan of the sun. Then his life, and identity, changed a decade later after he decided to go back to London and travel on to Continental Europe. In June of 1860, at the Texas border, the horse pulling his stagecoach went wild, and the runaway vehicle had an accident that killed the driver and a fellow passenger; when Muggeridge woke up nine days later in a hospital in Fort Smith, Arkansas, he had no memory of the period between a supper he had had in a wayside cabin, just before the accident, and the current moment. He had become deaf, lost his sense of smell, and was generally confused; fifteen years later, he would claim in an interview in the Sacramento Daily Union that the accident made his hair go from brown to gray.

Instant transformation was his thing in life as in photography. Muggeridge became Muybridge by the time he reached New York and was suing the stagecoach company. Eventually, after one of many trips to England, he replaced that humdrum “Edward” with Eadweard—which was the way the English kings spelled it—although for an exhibition of his work that went to Guatemala, he would be Eduardo Santiago Muybridge. The latter had the same ring as the name he had given to his son—Florado Helios Muybridge—who had been born in April of the previous year to him and his wife Flora, whom he had married in 1871 when she, recently divorced, was twenty-one years old to his forty-one.

By the time of his accident, Muybridge had taken up photography. While settling his lawsuit in New York, he applied for patents there and abroad for new devices for plate printing as well as clothes washing. It was the same period when Edward Clark and Isaac Singer and others were taking out patents for variations of the sewing machine; the idea was to make the processes of daily labor more efficient and render people freer in their everyday lives. Muybridge, meanwhile, was embarking in many directions at once. It has been hypothesized that the injury to his orbitofrontal cortex in the stagecoach debacle extended into the anterior temporal lobes, resulting in a lifelong impact on his behavior; he lost the social inhibitions he had before the accident, and at the same time became ever more creative than previously. In the course of the 1860s, he traveled to Paris at least twice, was a director of a company in Austin, Texas that owned silver mines as well as a director of the Ottoman Company and the Bank of Turkey. By the time he moved back to San Francisco in 1867, the photographer who, before being thrown from the stagecoach, had been the image of a correct and conservative businessman, was a wild eccentric, forever canceling business arrangements and flying into outrages. But he still managed to be successful. He transformed a horse-drawn carriage that only had two wheels into a portable darkroom which he called “Helios’ Flying Studio.” He began making stereographs—paired photomechanical prints or photographs made to stand side by side and viewed through a stereograph, a device resembling wide binoculars—so as to create a single three-dimensional image.

The stereographs Muybridge made as he took Helios’ Flying Studio to Yosemite and then Alaska attracted the attention of Leland Stanford, a wealthy businessman who commissioned Muybridge to do portraits of both his mansion and his racehorse Occident. Stanford told Muybridge that he was frustrated by the way that paintings of horses either galloping or trotting were never accurate in the way they depicted the positions of each of the horse’s four feet. In 1878, Muybridge used twelve cameras to do a sequential series of photos of a horse in full action. He connected wires to an electromechanical circuit in such a way that when the horse’s hooves tripped them, they automatically triggered the shutters of the cameras to which they were attached. Each exposure lasted 2/1000 of a second. The images of the horses in motion were published in magazines and became known worldwide.

Muybridge’s professional life zoomed forward; his personal life did the reverse. By 1879, he was doing series with twenty-four cameras at once. But this was only once he was released from prison. Shortly after Florado was born, the maternity nurse made sure that Muybridge knew the extent of a situation that was not new to him but with which he had managed to cope. His wife was having an affair with a family friend, Harry Larkin. On the back of a picture he had taken of Florado, Flora had written “Harry.” The issue of the boy’s paternity arose. Muybridge went straight to Calistoga, where Larkin worked in a mine. He showed Larkin a letter that Larkin had written to Flora, pulled out a pistol, and shot his wife’s lover point blank.

Muybridge went to the Napa jail gleefully. He was not only notably cheerful there, but fought the racism directed at “a Chinaman” by saying that the immigrant needed to be treated the same as everyone else. Leland Stanford hired a defense attorney for Muybridge, who told the court he had intended to murder his wife’s lover; otherwise, he gave two different impressions in the courtroom, one being that he had no idea of what was going on, the other sheer rage as he burst out into incoherent cries and shouts. His lawyer pleaded insanity, and Muybridge was acquitted on grounds of “justifiable homicide.”

By 1887, Muybridge was at work on his “Animal Locomotion” series. He produced 781 plates, with 20,000 series using the more than 100,000 images he had made. Plate 294 had the two rows of ten photos of the naked male tennis player, wiry and fit. The following plate was the one of the heavy-set woman shown above. She is dressed like an old-fashioned lady tennis player, a tam on her head, and sporting a black jacket and a skirt of black and white vertical stripes that resembles a beach towel. After using her racket to scoop up a ball from the ground—no mean feat, as anyone who has ever tried to do this knows, she remains stooped over while balancing the ball on her racket, which she holds with the face parallel to the ground, at knee height, like a serving tray. She then taps the ball into the air so that she can catch it and hold it ready to bounce as she pulls into her backswing and prepared to hit a forehand. Every tennis player knows that, awkward as the woman looks, what she is doing is not easy to execute—even for a more athletic person in lightweight breathable clothing.

The top row shows the woman performing this act in right profile; the second has her facing left; the third has us seeing her from behind. In a way, it is the principle of Cubist painting, which would emerge some thirty years later, where we see the same subject from different vantage points simultaneously.

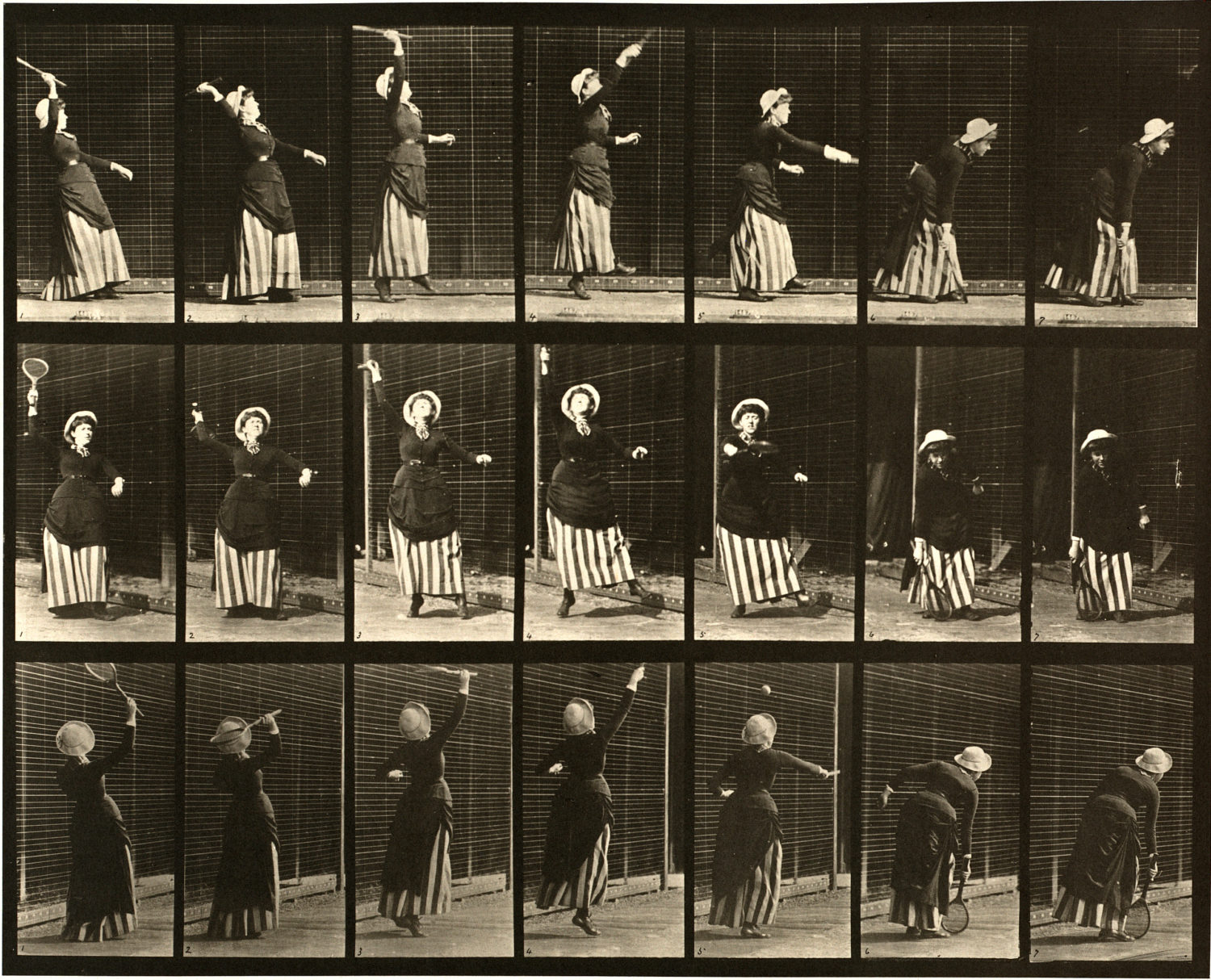

The following plate has images of the same woman in the same cumbersome outfit, only this time she is wearing a wide-brimmed hat of white straw. Here Muybridge had her preparing to hit an underhand shot—her form that of a beginner and a poor one at that—and making contact with the ball. Were the ball to succeed miraculously in going over the net, it would do so in a high loop, like an underhand softball pitch.

In the subsequent series by Muybridge, she is dressed as before, only this time she is serving. As with her groundstroke in the previous series, the woman shows herself to be an awkward beginner at the sport of tennis.

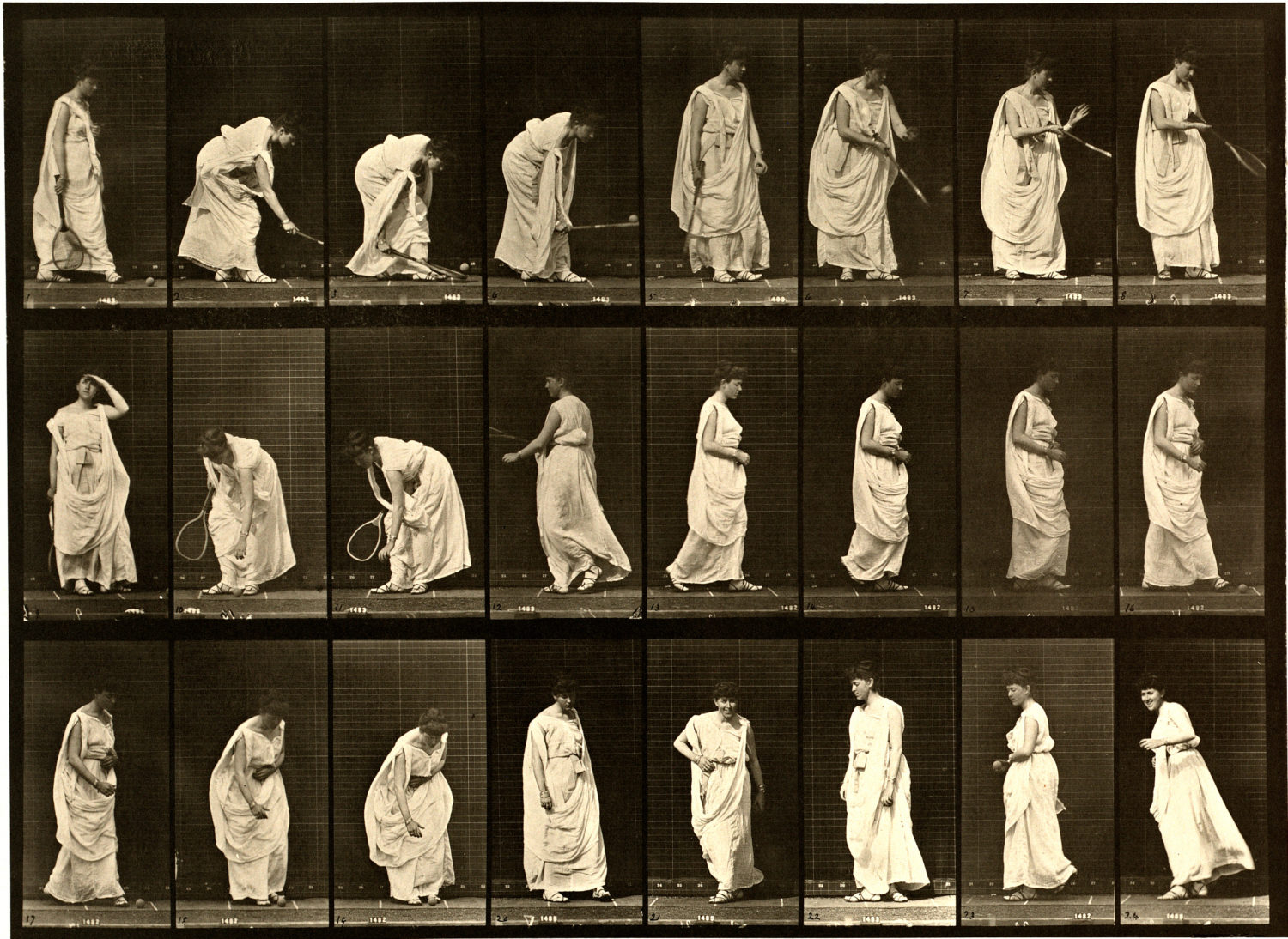

As for Plate 298, the last in Muybridge’s tennis series, we have “tennis player as goddess.” Muybridge quite naturally saw the movements of tennis as sacred. But why his graceful subject is in a toga and enacting yet again the act of tapping the ball, so as to maneuver it up from the ground, and then balancing it on her strings, is pure mystery.

And this time the rows of photos do not show the same series of actions as seen from different angles, but, rather, add further variation.

For all the mysteries, however, a lot is clear about Eadweard Muybridge. He was fascinated by the series of movements that people conduct with tennis racket in hand. He had a flare for the puzzling and dramatic, and used both costume and nudity to provoke his viewers, although whether he was conscious of it, or this was simply how his mind worked, remains uncertain. What is sure, though, is the pleasure, in whatever form, when that ball makes contact with the strings—a minor miracle for all who achieve it—and that it never fails to open new ways of seeing and appreciating the sheer splendor of tennis.

Article publié dans COURTS n° 9, automne 2020.