Tennis in Analog: A GOST Echo

People are obsessed with capturing the world they see around them. To remember, to inspect, to share. Whether it’s microscopy and radiography techniques developed to capture the structure of DNA, scintillation techniques to track the creation of particles or a combination of mirrors and lenses to capture that photo of your 1st birthday perched on the family mantle. Cameras are everywhere we look. Whether we recognize them or not in their many different physical forms. These tools we use to capture the world around us hold so much history within them, and just like every radiography technique holds the work of every scientist and engineer who’s pen and wrench led to its final form, so do our cameras.

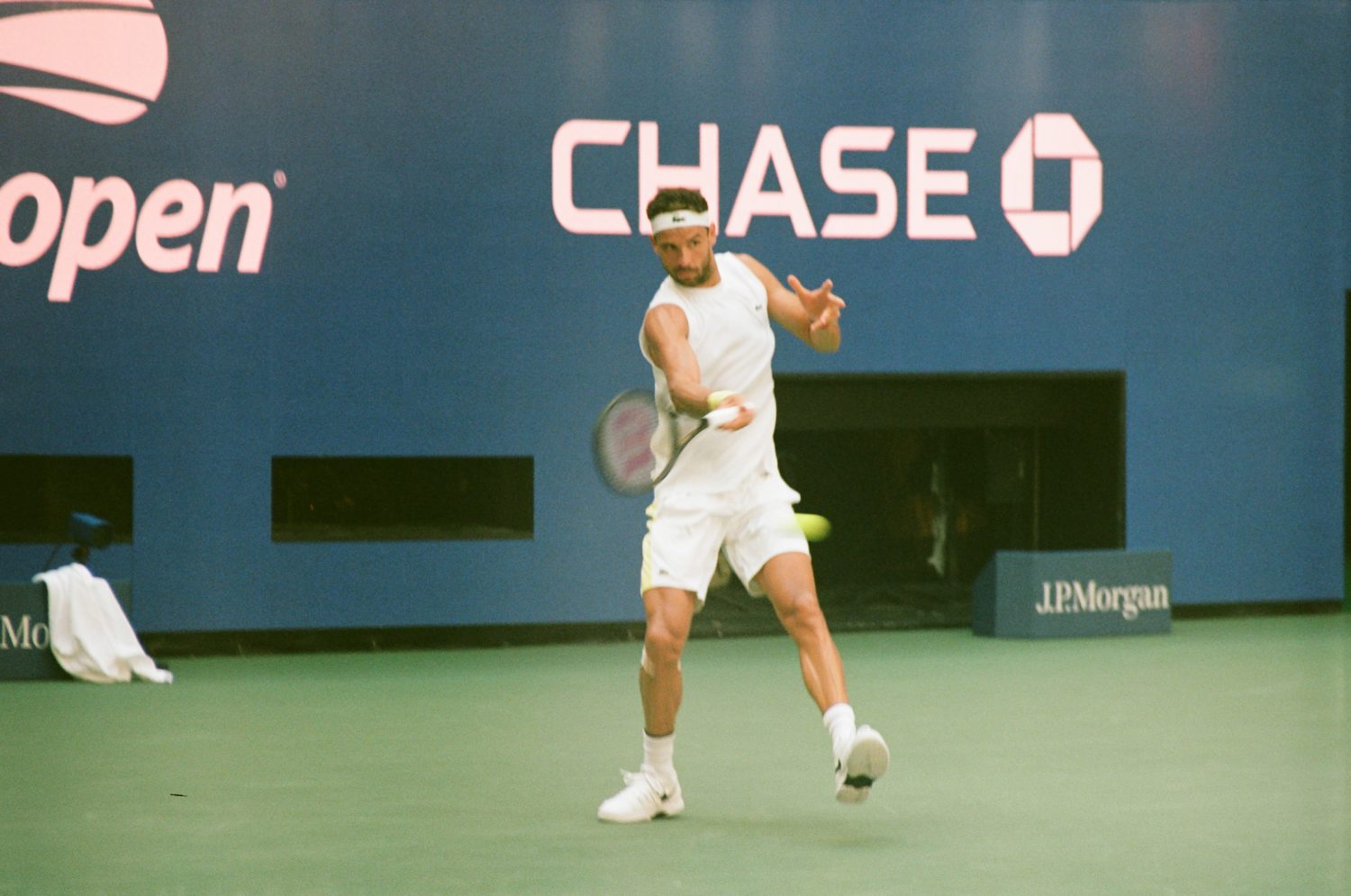

For me I use a Zenit-E. A camera which I cheerfully carried with me to the US Open this year in an albeit heavy bag, filled with rolls of film and my two preferred lenses: the Helios 44-2 and the Granit-11 telescoping lens. One for close up shots that specializes in a bokeh effect, the effect of having a central object in focus with background blurred, and one that allows me to get close up shots from further distances. Something of a necessity when shooting sports photography.

The Zenit-E camera gained popularity in the USSR and Eastern Bloc during the 60s. Its tagline was, and still is, that it was sturdy, built to last. And last it did. Carrying with it all its history. Tangible every time I pull out a new roll of film, glancing over at its film speed and mentally translating ISO 400 to the appropriate GOST value. GOST 350 for the curious.

You may at this point wonder what is GOST, and those of you unfamiliar with lab standards, building standards or photography may also be wondering what ISO is. In short they’re two standard organizations, but their history is anything but short. After World War II it became clear to the allies that there needed to be consistent and competent standardization. A long and painful war quickly exposed to them the necessity of being able to operate each other’s machinery in a time of war and/or great strife. The ISA, the predecessor to ISO, had attempted to do this with its founding in 1930 prior to the onset of the war and was, as the OECD documents themselves state, “the first international standardizing body with general competence”1. Emphasis on general, because as the war progressed it was clear that this general competence wasn’t as proficient as was needed. So in February, 1947 in Geneva, Switzerland ISO was founded. The name chosen because of the Greek meaning of the word “iso”: equal. But despite the name, not everyone was meant to or desired to use these standards. When the Iron Curtain was drawn so was a distinction in standards and practices. Where many western countries used the international standards system governed by the body ISO. The USSR and its satellite states used its own standards system: GOST.

This very history is why every time I load new film into my camera of varying speeds I perform mental calculus translating the ISO values of Kodak and Fujifilm to GOST. It can be easy at times to forget just how much history is tangible in the tools we hold. But the complex, and I’d argue beautiful reality, of the tools that we use is that they not only tell a story of our lives – How did we hear of this tool? Why was it available to us? – but the story of those before us – Why were they motivated to make it? What restrictions did they have to work with and why? – and more often than not these histories intertwine into a complex, personal and ultimately human story.

Now beyond my own camera and its own personal connection for me and my family I find that the medium of film has a specific human connection, one that’s allowed it to persist even with the advent of more technically superior cameras. Film is closer to the human eye. I don’t mean that it sees the image exactly the same. I mean that in that it’s altered, some may even stay tainted by the elements around it. A humid day can create an orange mist-like effect on an image, low light levels can make an image less bright and clear, in this way film has a sensory element just as our own recollections do. When you look back on a day you don’t see the image perfectly cast across the back of your eyelids, you see it as an amalgamation of sight, sound and touch. You look back on a humid day on the tennis court and you don’t only see the flashes of your friends and scenery, you feel the stickiness on your skin. Just like that developed film you can’t brush off that sensory effect. And just like that film you don’t look back on it in the moment. You play, you laugh and then a day or a week later you’re playing the scenes across the back of your eyelids, just like film waiting to be developed. That’s why I’d argue film has an overwhelming feeling of nostalgia, not because it’s an older method, though that doesn’t hurt, but because it’s imperfect and marked by its sensory surroundings just like us.

Don’t get me wrong, I adore the digital camera as well. I believe it has its own superpowers. The ability to look back on a photo in the moment and adjust is revolutionary. The wide toolbox you have at your disposal to control the outcome of a photo, the clarity and depth is nothing short of astounding. It’s a technical feat that so many hands have painstakingly worked on from labs all around the world. But this piece isn’t about that, it’s about film. So I hope as you look through these photos taken on my camera you’re able to feel something personal, communal and altogether human.

1 OECD/ISO (2016), “International Regulatory Co-operation and International Organisations: The Case of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)”, OECD and ISO.