Tennis and Beyond,

as Seen by Brighton Artist Anna Carlson

Anna Carlson is a multidisciplinary Brighton artist whose exploration in work and life is boundless, as she dabbles with the traditional and breathes new life into it. Art grounds her, and provides her with a release, with an oasis of calm amidst the chaos of modern life. She travels, she absorbs, and she then generates her own ideas. Light and inspiration can be found in the most unlikely of places. The pandemic has provided us all with challenging times and how it has shaped our current lives is no small thing. Anna is plotting her return to a more active sense of individual creation, post-pandemic restrictions, despite having been busy throughout the past year or so as she took the time to look at her surroundings and explore things in a more communal sense.

Anna is cheerful and animated, just like the spring day on which our paths meet in the middle. Her artworks possess the essence of this, wonderfully capturing her lively character. The energy of her ideas, how she discusses them, and where she intends on taking them fill the screen, permeating the entire conversation. She is influenced by several key figures, though she tells me that David Hockney has played an ongoing role as “a thread through her artistic years”. She mentions Laurent Perbos and in particular his tennis court that went down the stairs, revealing a whole world of possibility for Carlson. Hockney had caught her eye as an eighteen-year-old at art college with his works set in LA and as she says, the “clean lines, architecture, glamour and people, capturing both the sexy and the mundane” had a huge impact on her and what was to come. Another artist, Richard Graville, makes clean, precise art with representations of the natural world. She also mentions Rachel Whiteread, Bridget Riley, and Bertrand Fournier. These inventive figures all possess keys that unlock Anna’s own blend of familiar and yet distinctive art. As she herself states, she “likes finding a language out in the world”. With her college background in art and design, Anna has had a profound experience of self-discovery, and educating herself in the creative realms of sculpture, architecture, and painting, she is something of a shapeshifting chameleon.

Pre-art college, she says that “Like any human, I spent my childhood drawing. Thinking back on it I was definitely drawn to the soothing nature of constraints, form, clean lines, and a limited colour palette when I was little; I drew and coloured in a lot on graph paper. Making patterns out of rules, exploring colours that worked together. My favourite colour combo when I was little was red, bright blue and yellow with black and white – primary colours essentially – and I can see these colours coming out in the work I do now”.

Over the years, as Anna says, she has “gravitated towards order, lines, shapes and colours and the interactions between them, the real precision in art”. She goes on to refer to her chaotic childhood in which she was over-stimulated and how the response to that has been to find something to soothe, an opposite to the travelling, the city, and the outside life. It has taught her to be precise and ordered when she makes art. It is for both herself and those attracted by her work that reintroduces, reinvents, and even repurposes familiar shapes and objects.

That is where tennis comes in and the irresistibly precise and easily recognisable structure of a court and how it transports us to times and places in our own lives, to relive all manner of past moments. Anna sees a lot of parallels between art and sport. She says there are “misconceptions about art and artists much like sport”, then breaking down her understanding of what makes them both, stating percentages of “5% talent, 95% work and practice”. Since exploring her own concept COURT, she has seen the parallel between art and sports in relation to taking them up, the practice, psychology and how to get better, as well as how art can amplify the reach of sport. It can bring attention to sport, to any activity, it can be the “nice smell coming from the kitchen” that draws people in, further adding that we live in a “very visual world” and art can add “fairy dust” or “colour” to proceedings.

The precision of the dimensions of the tennis court and other sporting courts and pitches appeals greatly to her. Carlson installs her own courts in settings that are anything but ordered, finding all kinds of different backdrops inviting, viewing the juxtaposition to be a spectacular source of inspiration for her creativity. When I ask what inspired the COURT project, Anna tells me that three years ago she saw a photo from somebody’s holiday with all these colours on the floor of a gym. She then did some research around sports courts and the language and discovered a universal configuration of tennis (and basketball) courts. She realised it was a collective language. This tiny flame inspired by a mere photo grew into a raging inferno of a project, thus demonstrating how art often came from almost nowhere.

“When I first started exploring courts, I was travelling a lot with work, and I was struck with how ubiquitous they are as a form in city and countryside landscapes wherever you were in the world” Carlson states, before continuing, “I also loved the different contexts you might find them in; there’s a basketball court on the coast by me in Sussex that is at the base of the white cliffs, that is always covered in chalk; there’s a football field of my local non-league club Whitehawk FC which is in the middle of a sheep field in the Sussex downs; then in Sicily I loved the tennis courts in the centre of Palermo surrounded by cypress trees and buildings that are centuries old. I also love the space that’s given to them – that’s given to play – how indulgent a concept when public spaces and cities are filling every square mile up with housing and developments”.

She then considers the enormity of the past and how faithful we have been over the years to the early forms of our sporting shapes, courts we all know, saying “I love the history they hold – the origin stories of the courts and their markings and the rules of the games. How they were iterated in their first few years or decades but have remained largely the same since. And the idea of play within constraints, within rules; that’s a concept that’s helpful in an artistic practice too”.

Anna herself played tennis at school and received private lessons as well and then went fifteen years without playing again, until more recent times, in which she has returned to the sport as what she considers a total beginner. She says that she cannot play, but she loves hitting the ball and watching the sport. She even loves the sound of tennis, the one sport she states being able to have on in the background listening to as she works, and she finds it a soothing and even fascinating and unique algorithm – a special sound almost akin to music production with its multiple layers of sound. She goes on to say that the feeling she gets when watching tennis is “weird nostalgia for something I am not involved in”. Looking back her memories of tennis centre around viewing Roland-Garros and Wimbledon on the television. Anna says that Wimbledon itself is “quintessentially British” and reminds her of “strawberries, the middle of the summer, and British culture along with the Glastonbury festival” adding that it has a sweet and sentimental tinge to it.

When asked which names of the sport stood out, she immediately says, “Serena and Venus” and “the Nadal-Federer rivalry – the tidy Swiss and the sweaty Spaniard – the difference between them, the yin and yang” of the pair. She also says it will be interesting to watch the future career of Coco Gauff unfold.

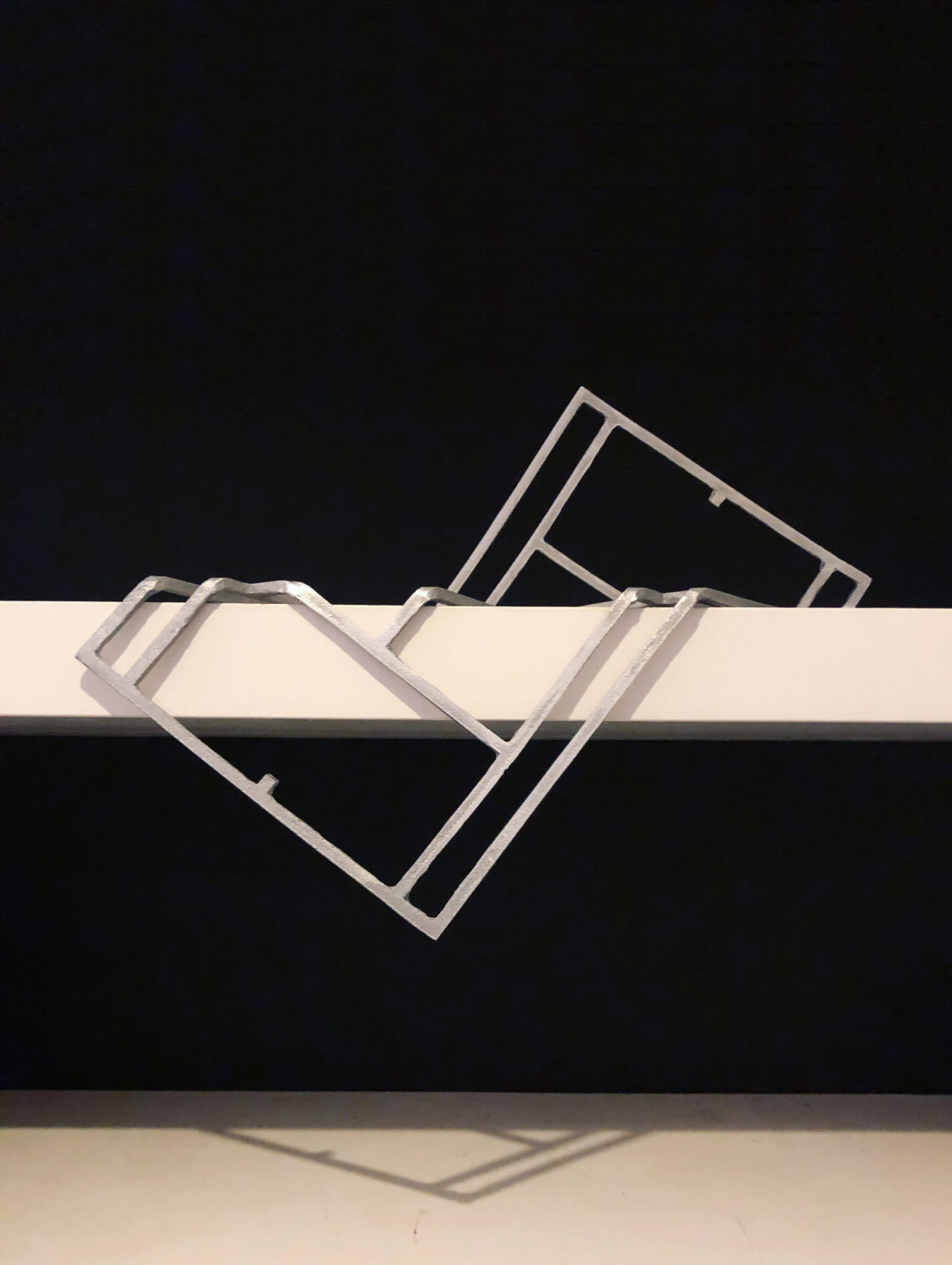

In addition to her COURT project, she has birthed a second tennis-related concept called ‘Second Serve’, tennis clearly having left a mark on her consciousness that is now seeing the fruits of her creative sparring. She explains this more recent idea in further detail – “Second Serve was an idea I had when I started to notice all the tennis rackets in charity shops and boot fairs that I couldn’t imagine there is much of a market for, given that people can buy cheap new ones online. I also realised they were aluminium and wondered if they could be repurposed in any way. So, I approached a local metal forge and explored casting one of my bent court sculptures out of some melted down old tennis rackets. The first prototype was ‘Second Serve’ – which I sacrificed one of my acrylic courts to make the mould for – it had broken in places which meant I had about 100 hours of metal filing to do to fix some spills, but largely it worked! My mission now is to explore better forms for making casting moulds that can give all these old aluminium tennis rackets a new lease of life!” She continues, “I really want to explore sustainability of materials – reusing old nets and rackets and even sportswear. There are some amazing materials that become obsolete in their first life that could have an amazing second iteration. My Second Serve project is a start of this – exploring new forms for melted down old aluminium tennis rackets”.

Engineering new concepts and flamboyant art out of existing shapes and known sporting courts would seem a lofty challenge, and yet Carlson adds a dimension to our existing perspective of a tennis court and where one might traditionally see them. “I love playing with shapes, colours and rules in my work, in my drawings. I also love with courts in particular that they can evoke so many emotions, memories, and associations when people see the markings; particularly when they are highlighted or out of context. At my solo show ‘COURT’, so many people at the opening told me their stories, their childhood memories that were evoked by being in the space. As well as my paintings and works on paper being hung, I had painted the space with a basketball court and had sounds of tennis matches and basketball games playing low level in the room”. She then returns to the sonic aspect of tennis by saying “The sound of sport is especially evocative for me; the sound of tennis matches particularly. Memories of summers at home and Wimbledon on the TV in the background. The layers of the sound of a match so artfully weaved together by sound engineers; the ball hitting the racket, the swoosh of the racket through the air, the gentle ebbs and flows of the crowd’s reactions, the distant grunts from the players.”

Situating her courts in remote and even grotty urban settings is a dazzling feat for a young woman constantly evolving, challenging herself as well as others, and her surroundings. Regarding limitations, she says “I love to think big – let my mind dream of huge installations I would do in a major city if I could – but I find in the making of work it helps me to have a limited palette of colours, rules and materials to work with. I can be creative then; finding all of the combinations I can create within those limitations.” By slipping the familiar into unexpected territory and challenging pre-existing notions and ideals of what our sports should be, Carlson even opens the door to new fans of both art and sports.

When we discuss the unavoidable pandemic, she states that “It definitely shifted my mode of working. I went from my solo practice and mission of exploring one thing to looking more around me, to how I could share artistic practice and play that I get so much comfort from with my friends and loved ones. I started an art club with friends and their kids, sharing weekly challenges and posting everyone’s art on an Instagram ‘gallery’ in a weekly art show”. She continues “I also started working with a local artist network, as part of a desire to connect with the community in my own town and to help other artists produce and realise work. Now that things are opening up again and the weather is getting warmer, I’m starting to feel sparks of inspiration again for my own work which is an exciting feeling”.

The Cambridge native – who grew up in Kent before relocating to Brighton in her mid-twenties – hopes to leave something tangible behind, something that might well leave an indelible mark on the imagination of children and adults alike, all perceptive to art in recognisable forms and susceptible to the desire to play (as well as to explore formidably new terrain via the familiarity of courts and pitches). She wants people to be able to play with, experience, and enjoy her artworks. Carlson says “I’ll never stop (referring to making art in her lifetime). I have a deep desire to create an intervention in a public space. To have the autonomy to inspire joy, curiosity and wonder”. She wants to make something for the sole purpose of people using it to play with, to actively enjoy, explaining, “I’d also love to create an installation in a public space that people can play and interact with. Exploring the necessity of play for our ongoing development as humans and carving out public space for it”. In the future, for example, she hopes to construct a giant tennis court climbing frame, and not necessarily in a gallery as the key idea is that people can use it, play with it, experience its magic.

The life of an artist is a puzzle, a patchwork of endless different sources of inspiration all contributing towards something new, and Anna Carlson is proof of this. She is an artist with a grandiose vision to say the least. Her creative forays stretch far beyond the realm of tennis, and this quest for escapism for the creator, the art lover, and those connected to the sports in question drives her. She signs off by saying “I’m just making work for the fun of following my curiosity. It is something I need as much as exercise and I genuinely believe an artistic practice of some form can bring joy to anyone’s life. It’s a fundamental part of being a human.” It is this vital sense of invention that is a release, as well as a fun way of expression and sharing an experience that defines Anna’s journey. While her shapes may be familiar, the experience Anna wishes to deliver to people is anything but. If you have not encountered her work before now, the chances are that her works are going to crop up in future spaces and catch you surprisingly, and pleasantly, off guard. If you know of a local setting perfect for one of her courts, it might indeed do to just watch that space…

Story published in Courts no. 1, summer 2021.