Serving Up Hope

On an unusually chaotic day in the typically clamorous neighbourhood surrounding the red dirt courts of the Acholi Quarters—one of the poorest communities in Kampala—former touring pro Vania King stands among six rows of young children, clasping her racquet while they grab theirs: colourful, plastic prototypes made specifically for young players. She shouts “ready position” and the kids mimic her jumping in place, feet shoulder-width apart, both hands on the handle. Next up: shadowing King on the forehand and the backhand. Out of nowhere, King then grabs a bucket of big red balls and tosses easy hitters, while student after student aims and swings—some of the youngsters get a piece of the spongy, rotating orb used for beginners.

“Nice try! It’s OK. Keep your eye on the ball!” King shouts encouragement. King had touched down in Uganda just a few days before in July 2022 directly from England, where she had played in the annual Wimbledon Invitation Doubles. She was hauling seven or eight bags stuffed with balls, racquets, shoes and bright-blue-and-pink-t-shirts with the words “Serving Up Hope” on the front—the “o” in HOPE a stencilled tennis ball with a heart in the middle. They promote King’s NGO, founded in 2020, as well as her new passion and career since retiring from the professional tour just two short years ago.

“I had no idea that this would become what it has,” King says after the session. “Running an organisation is no easy task, but tough enough as it is, tennis has given me so many interesting, intersecting experiences and paths, I wanted to do something.

“We started this at the smallest scale possible—30 kids playing every week—and now we currently teach 120 students annually.” Last winter, King took two stand-out players to South Africa to play their first international tournaments.

In her heyday, King played for full stadium crowds at Wimbledon and the US Open, reaching a career high rankings of WTA No 3 in doubles and No 50 in singles, while picking up two Grand Slam Doubles championship trophies—Wimbledon and the US Open—along the way. At age 30, however, hampered by injuries and looking for change in her life, King called it quits at the 2021 Volvo Open in Charleston, South Carolina and returned to Uganda where she had found a mission. “I fell in love with the place and the people and I saw incredible need,” King says. “And I realised that volleying drills can be done anywhere—you just need a racquet and a ball.”

Serving Up Hope is one of several successful efforts to reignite professional tennis in sub-Saharan Africa. Previously led by South Africans in the 1960s and then Kenyans in the 1980s, from around 1995 to 2015, the continent experienced a drought of talented Futures and Challenger-level players, especially juniors, as governments struggled with stability and tennis associations across the region staved off corruption. Africa still has only one professional in the Top 10 of either the WTA or the ATP tours—WTA No 7 Ons Jabeur of Tunisia—and none from sub-Saharan Africa in the top 100, unless you count players whose parents were born in Africa and emigrated. But over the past seven or eight years, beginning with several International Tennis Federation (ITF) interventions, Africa is experiencing a tennis resurgence that could allow several players from previously unrepresented countries finally reach the top echelons of the sport.

“We have a lot of good players in Africa,” says William Ndukwu, a London-based tennis coach and father of an emerging junior. Ndukwu started out as a ball boy at a Nigerian club and finished his career on the ITF World Tour, and has now coached his daughter, Alisha, 13, to the top 1,000 ITF Juniors in her first year. “But when you’re in a match and think about paying rent by winning the next game or helping your sick mom by getting to the final, you don’t play very well. That’s been the situation for a long time,”

The story of Africa’s emergence and then resurgence in the tennis world actually begins in 1971, when while waiting for the apartheid South African government to approve his visa to play at the South African Open in Johannesburg, Arthur Ashe and his pal Stan Smith went on a 2,500-mile tennis expedition of six African countries—Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, Nigeria and Ghana—giving tennis clinics, granting interviews and playing exhibition matches. Over the course of the next five years, Ashe played the first integrated tournament in South Africa, discovered French sensation Yannick Noah in Cameroon, attempted to set up a pro-tour in sub-Saharan Africa and quickly left that behind when, while playing at a tournament in Lagos, Nigeria, he was marched off court at gunpoint, during a political coup. After that, Ashe turned his efforts to tournaments in the States, Davis Cup and his health.

More than 40 years later, several players from the Sahel region started gaining the attention of the ITF. Realising their potential, the ITF began its Grand Slam Player Development grants, giving Africa’s top players up to $50,000 to cover touring expenses and coaching. “Sometimes, a city doesn’t even have a sports shop that sells racquets. If you find one, it can ultimately cost three times the price of one in Europe,” says Frank Couraud, the development projects administrator at the ITF’s central office in London. Next, the ITF opened training hubs in Casablanca, Morocco and Nairobi, Kenya, to nurture future professionals’ ability—an effort that was recently relocated to Sousse, Tunisia, thanks to a partnership with the Tunisian Tennis Federation. The African Regional Training Centre will offer state-of-the-art facilities and provide talented players aged 13-18 with full-time training, schooling and competitive development.

It’s a good start, says Wanjuri Mbugua-Karani, the Secretary General of Tennis Kenya and a former top-five player in her home country, but it’s still not enough. “The big corporations… see Africa as a small market and therefore, no need to invest,” she says.

Mbugua-Karani estimates the required amount to be about $100,000 a year. “Africa has been able to produce very good junior players, but at the age of 16–18 when they should start playing professional tournaments, they lack the funds for travel and accommodation. “Africa needs to find a source for individual player sponsorship and for tournament sponsorship so we can hold ATP and WTA tournaments on the continent to greatly reduce the amount of travel expenses and foster a tennis culture here.”

Into this situation, King somehow stumbled. Her story starts out rather conventionally: on a break from the Tour, King went on safari to see mountain gorillas in Western Uganda. Following that, she started making a couple transcontinental trips per year to Uganda, always exceeding her luggage allowance. Soon enough, King decided to make her ventures legit, founding Serving Up Hope—one of the few tennis non-profit development organisations led by Grand-Slam-winning professional tennis players. It is currently the only one in Africa to offer both tennis lessons and STEM programming for underprivileged children.

“Playing tennis, we are so hyper focused on what we are doing—we sacrifice everything for it,” King says, explaining the reasons she is one of the few players to parlay a former tennis career into NGO work. “It’s not really until I stopped that I could try new things.

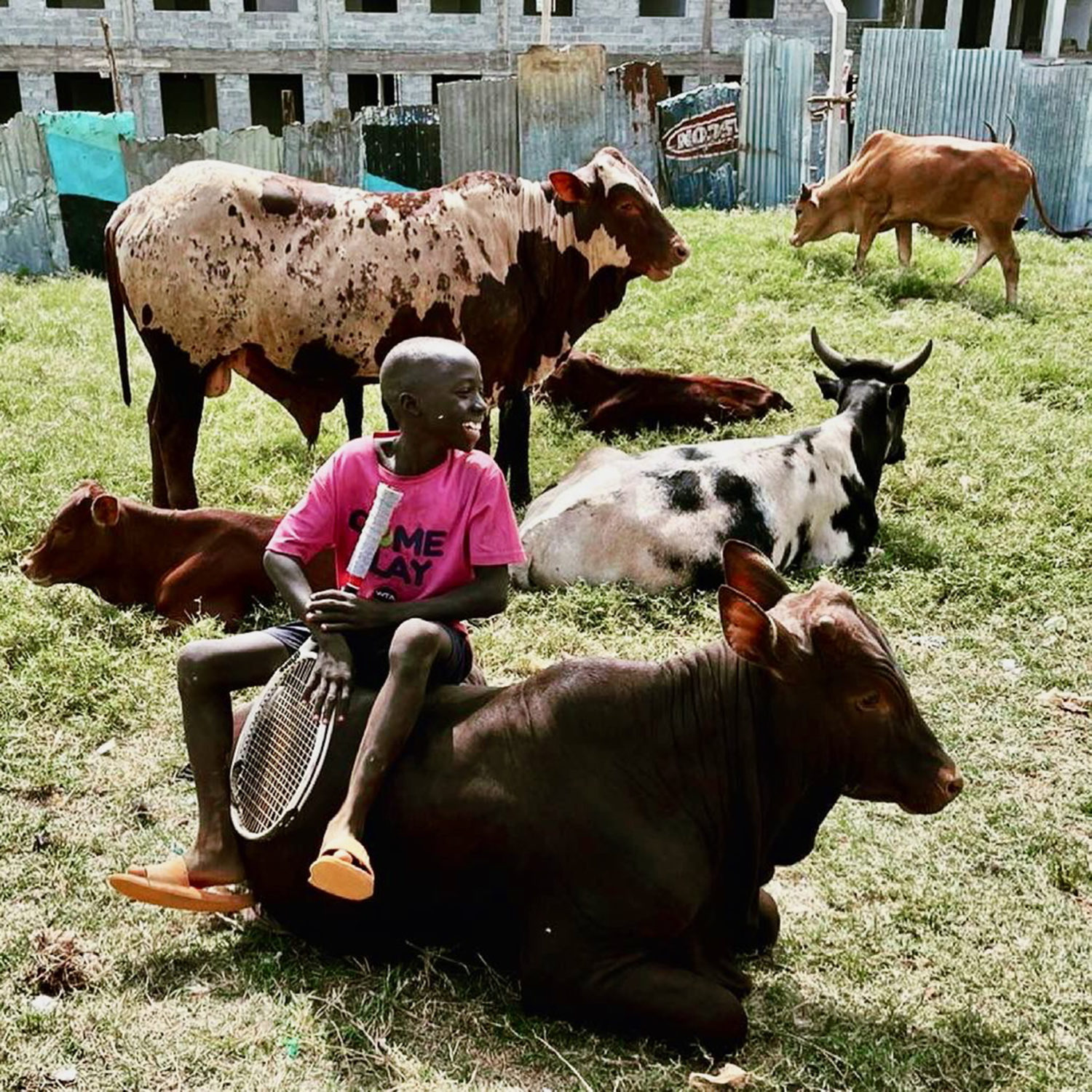

“These are kids whose families make less than two dollars a day. For them, tennis is an opportunity that they otherwise wouldn’t see. That’s our goal—using tennis as a platform to provide opportunities on and off the court.”

While King takes on Uganda, many other local tennis associations and other patrons, especially Nigeria and Ghana, have started putting more money into tournament and training infrastructure—many with the aim of gaining junior sport scholarships in the States. “Our foundation basically tries to get players ready for these scholarships. We pay for their SATs, ensure they have their O levels and also sponsor them to play tournaments so that they can improve their level of tennis,” Fuad Quadre, the founder of Fusion Tennis Foundation, told Nigeria Tennis Live, a site created to cover local tennis, including juniors.

“Apart from helping them boost their rankings, it will also improve their tennis to a reasonable level that can impress these schools where they will be applying for the scholarship,” added Quadre, the older brother of Oyinlomo Quadre, ranked No 92 in ITF Juniors and a sophomore playing at Florida International University. “These are some of the things the kids are not privileged to have, that’s why our foundation is there to support these kids to help them get these scholarships.”

A few of the main factors that programs such as King’s offer—thanks to her connections to the WTA—are the provision of equipment, which is hard to get shipped to needy players in Africa, exposure abroad and transnational and international visas. The African Union had once looked at scrapping visa requirements for all African citizens as part of its “African passport” campaign, but that has been abandoned until at least 2063. King also provides a discriminating eye in terms of choosing coaches and administrators for her program.

Most of all, the majority of sub-Saharan African countries have one singular problem that the majority of strong tennis nations have overcome: a lack of investment foresight by the sport’s kingmakers. Compared to Europeans who side-step into the U.S., Europe and most other tournament countries, where they can play as many matches and talk to whatever investors they please, “Africa needs the big sports brands to come here,” Mbugua-Karani says. “We need to bridge the gap where they turn pro. This is an area of investment potential in Africa, and I believe that the time of Africa is coming very soon.”

But besides King and former pro Mary Pierce who coaches from Mauritius, few former players want to get into the NGO game. King has currently put a bit of a halt on expansion into more countries as she makes plans to build a tennis centre in Uganda, but she has found a new passion project.

“I’ve been working with the Ugandans hand- in-hand for two years now and it’s been challenging, learning and growing through that—I’m not trying to be the foreigner that dictates things but to make this a joint endeavour,” King says. “Seeing the kids transformed and how I have transformed with them has made it incredibly worthwhile.”

Story published in Courts no. 4, Summer 2023.