Painting Elbow Translation

When does override our past impressions?

In the agglutinate mass of media where our competing identities intertwine, it has been said that we, as viewers of modern art, must separate the man from the craft. If starting our journey from this postulate, we must just as urgently separate the artist from his legend and the tennis player from the man, otherwise we cannot find our way to its meaning. Taken at face value, this cautionary introduction makes sense.

This way of looking is all the more reasonable if the art attempts to tell a story of complicated and confusing origin — a narrative of disparate voices and perplexing history. The viewer must therefore unwind this thread straightforwardly, avoiding knots along the way. Otherwise, the account falls victim to its own complexity. Some details: the man is Rinus Van de Velde; the artist is a merger of the real man, Rinus Van de Velde, and a mythologized world of his creation; the legend Van de Velde has created is that of a man in a drawing purporting to be someone else; and the tennis player is the common bind tying it all together. All these personas meet daily at Rinus Van de Velde’s studio, and over the course of several weeks, create a history of several lives, which accumulate and overlap, always similar and always different. Evoking the work of Van de Velde is therefore tackling the writing of a Genesis in motion — the telling of simultaneous and competing stories by an artist who made his own reality infinite by crushing his outside existence. His art refuses to separate anyone from anyone else, or anything from anything else. Van de Velde is Everything. Everywhere. All at once.

In the beginning, there was Antwerp

André Agassi and Brad Gilbert, Pete Sampras and Paul Annacone, Rafael and Toni Nadal, Carlos Alcaraz and Juan-Carlos Ferrero, Rinus Van de Velde and Tim Van Laere. I’ll leave it to you to silently hum the theme song of the buddy-rival British television action-comedy “The Persuaders,” served with the peppery tomato-mayonnaise Belgian sauce to accompany the meeting of these two frites.

We don’t really know if anything predestined Tim Van Laere to become a professional tennis player. When he retired from sports in 1995, on the other hand, you had to be in on the secret of the gods to know that Van Laere was preparing the opening of his own contemporary art gallery, and that this gallery would become, in its brutalist setting softened by the predominance of pink, the Mecca of the European art scene. At that time, Van de Velde was age 14, preparing to give up tennis in favor of cigarettes. I may digress, talking about everything about nothing, but bear with. In this relationship, tennis symbolizes everything: 15, as in the number of years since Van Laere and Van de Velde have collaborated; 30 as in the number of cigarettes that Van de Velde smokes every day; 40 as in the current age of Van de Velde; and finally, game, in which both collaborate on A Life in a Day, the latest creation of the artist on which we will return.

Because before A Life in a Day, a decisive meeting occurred. It dates from 2011, when Van Laere and Van de Velde began a collaboration that would make them change dimension. Having graduated five years previously from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Van de Velde first devoted himself to sculpture before finding in charcoal the ideal medium to tell his fictional autobiography. An autobiography nourished by the great elders: as children learn by copying their elders, Van de Velde incorporated drawings by Van Gogh, Hockney and Rembrandt into his work to create a symbiosis between art and his history.

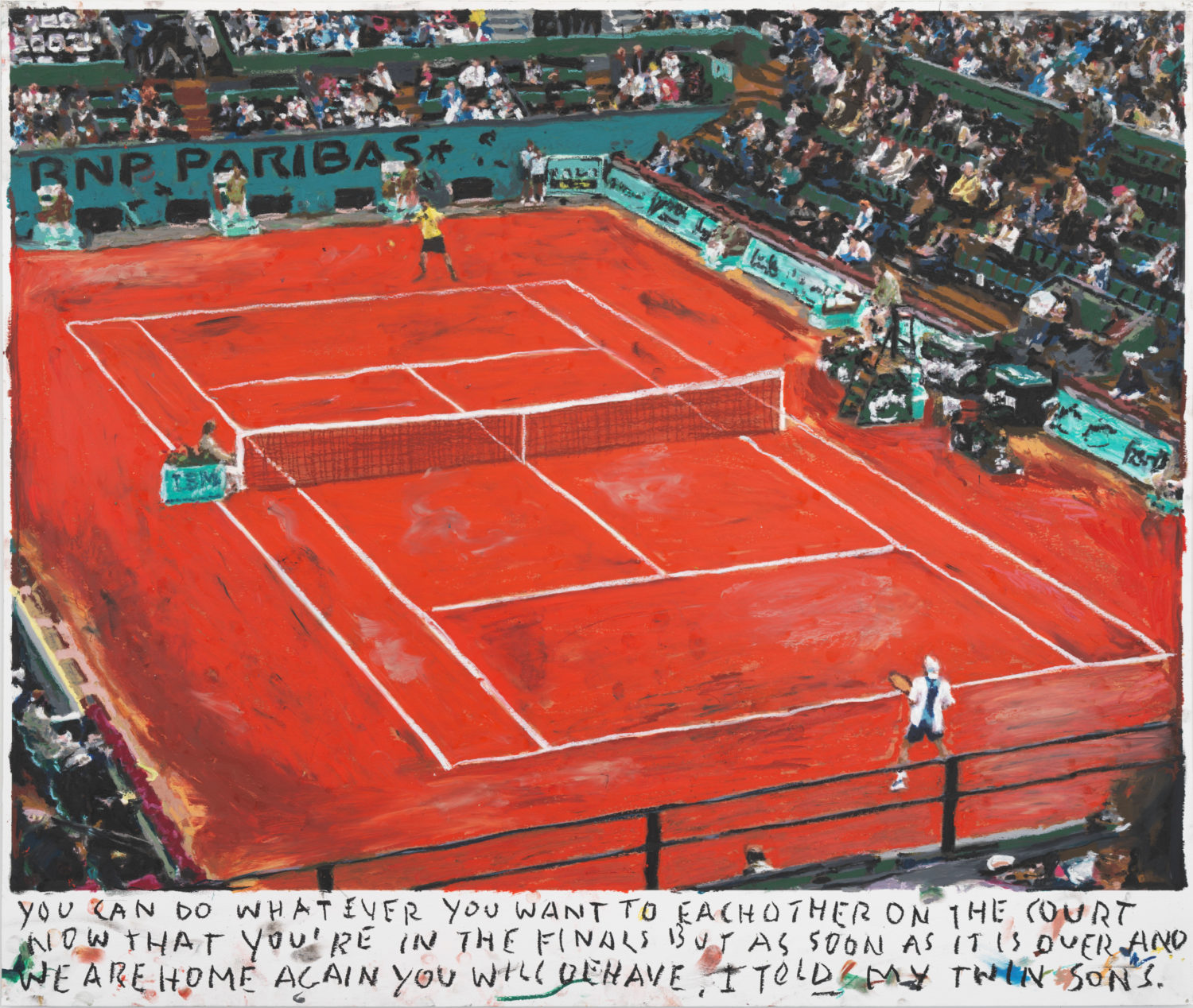

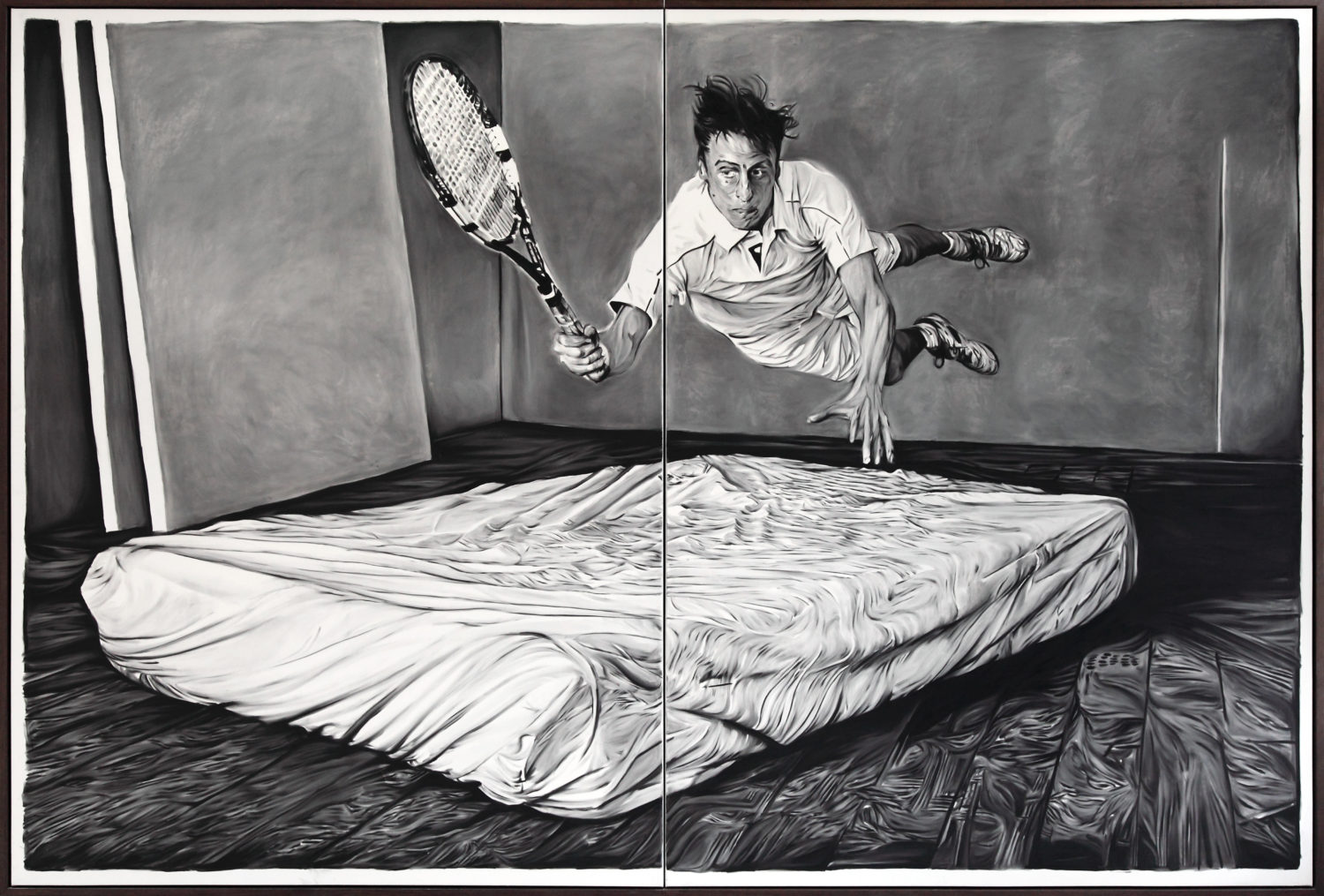

On these gigantic black and white panels between Lynchian neo-noir and gothic tale, Van de Velde stages an alternative version of himself — one that explores the universe of possibilities. Van de Velde likes to dream about his life and act it out. He is sometimes a prisoner in a disturbing green room, regularly a tennis champion landing on a mattress, every now and then a grand-master chess player and occasionally, a sailor in a storm. All of these transitions take place in his workshop, which he never leaves. This propensity for daydreaming is not very compatible with the obligations of the artist. Van de Velde finds in Van Laere his anchor in reality, if reality exists.

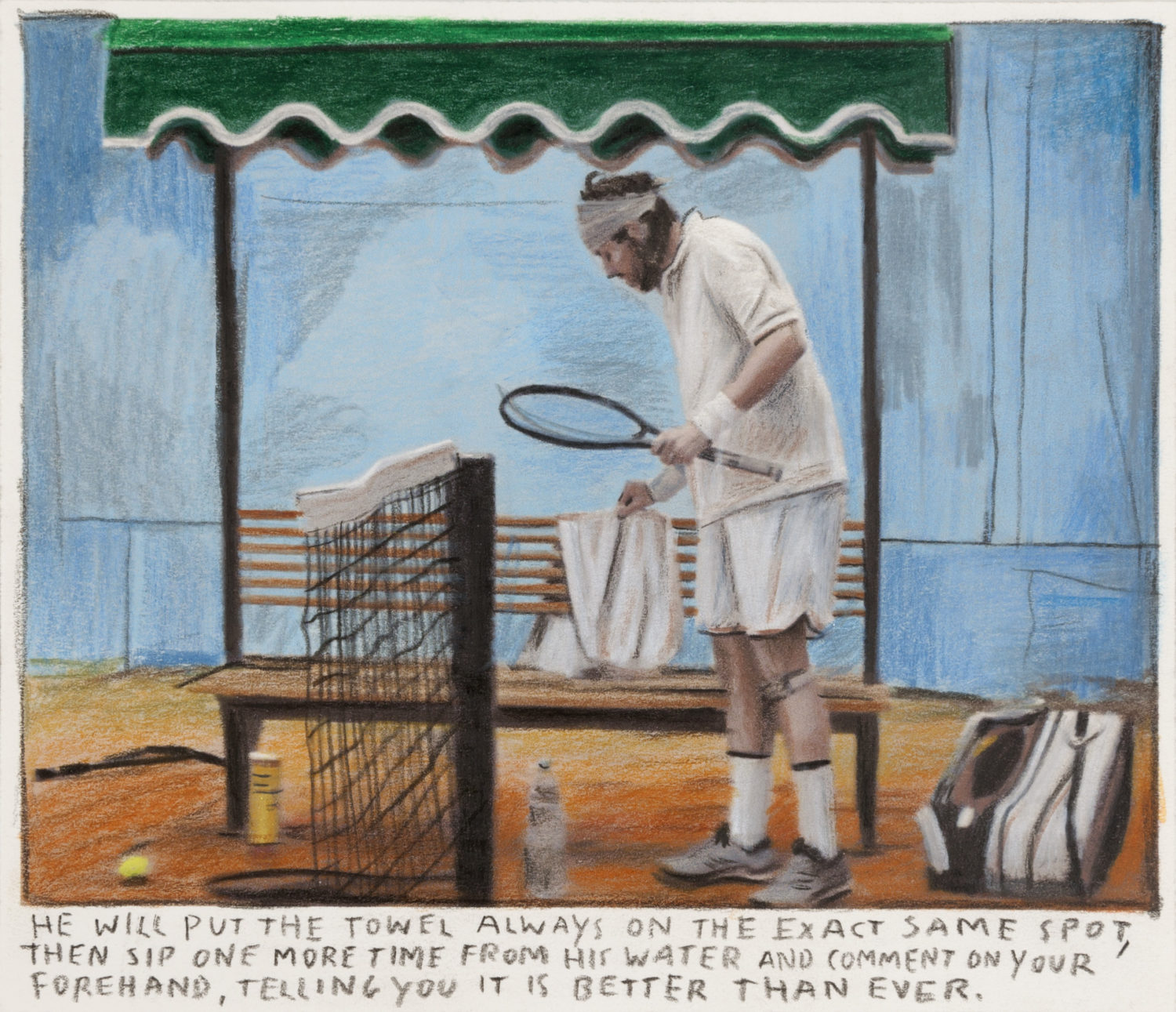

Van de Velde also describes Van Laere as his mentor, off whom he can bounce his ideas. If the artist is isolated in his studio like the tennis player on the court, he needs a connection with the outside world (and a little coaching). Like a coach in an athlete’s box, the gallery owner represents the artist, organizes his life. He is a physio, trainer, mental trainer and agent. He is also a source of valuable advice when a shoulder aches from drawing.

Every reality has its downside

In 2013, Van de Velde’s shoulder was struck by pain, not unlike a tennis elbow. Unable to weave the threads of his parallel linearities, Van de Velde was forced to face reality. He turned to who advised him to get back into tennis to strengthen his drawing arm. The advantage of having a former high-level player on one’s side: a certain number of putative teachers who are a little more attractive than Michel, former 15/3 at Puy-en-Velay. Tom Vanhoudt is one of them. Formerly 200th in singles and 36th in doubles, he trained Ruben Bemelmans. As a result, Van de Velde could well reach the top of the rankings in one or the other of his realities. But if the photos seem to attest that Vanhoudt had a two-handed backhand, know that the official sites of the ATP and ITF insert some doubt, specifying only his “unknown backhand” — just as if in 10 years of a professional career Vanhoudt had “only hit down-the-line shots.”

The anecdote is savoury when we know that before getting closer to Vanhoudt, Van de Velde had taken up tennis with another coach who had recommended the one-handed backhand. But Van de Velde, dissatisfied with his progress, approached Vanhoudt — without telling his first coach — to take additional lessons… lessons during which he hit a backhand with both hands.

From one session to the next, the only tangible thing in Van de Velde’s life was the mediocrity of his backhand, with one or two hands.

With the two coaches unaware of the existence of the other, Van de Velde was able to transpose his taste for parallel lives into the real world, hiding the immense pleasure of being both Federer and Nadal behind the shame of this very innocent betrayal. As tennis eased the pain, however, Van de Velde returned to his work as an artist, while continuing tennis with Vanhoudt, with whom — there is no doubt — he had signed with both hands.

Legends of legend

In life or in his works, Van de Velde is therefore, a storyteller of legends who uses said (legends) to propel his art into a new dimension. Because his works are systematically accompanied by short voice-over texts, which imbibe his scenes with a mysterious aura or a continuity in the thoughts of his alter egos. These voice-overs also serves as proof that the images that Van de Velde offers are only snapshots torn from sensitive and complex realities, from stories written elsewhere. On the representation of an empty tennis court there is this note: “Now I have to find my big serve”. Van de Velde claims not to have found it yet. However, he met both a big server and an art lover in the player Reilly Opelka.

“Mr. Pink”

Action cam. As a good Sunday tennis player, imagine yourself standing on a court, as far as possible from the service line, your back leaning forward and your legs anchored in the ground, ready to jump left or right to return your opponent’s serve. Now imagine that opponent is Reilly Opelka. He decides to kick it. Are you going to touch the ball?

No. Even you, there, deep down, you are sure that if you anticipate the correct side, you will be able to block the ball back. I will tell you, no. You don’t touch the ball.

Van de Velde didn’t touch it either, but his work touched Opelka. And by finding his big server, Van de Velde made a friend who wasn’t just contented buying works from him and coming to the 2021 U.S. Open in New York with a pink paper sack from the Tim Van Laere Gallery (which could have earned him a fine for non-compliant bag). Rather, Van de Velde’s real-life tennis alter-ego introduced the artist and his mentor to Venus Williams at the 2022 edition of Wimbledon. Since then, he’s been an extraordinary ambassador for the gallery even if the injured Opelka has not played for a year.

Trains are leaving

James Dean, Reilly Opelka and Venus Williams. Glamour: the life of Van de Velde? Precisely to demystify this romantic idea, Van de Velde, for his new exhibition A Life in a Day, to reverse his habits. Rather than delivering to the public selected pieces of a fictional autobiography, he decided to show the reality of his life by mixing the magic of daydreaming with routine. Reopened to color following the discovery of oil pastels, Van de Velde began to use beauty and brilliance to construct the theater of his daydreams on a canvas. In his habits, Van de Velde has not changed anything: he gets up and he smokes and he paints and he smokes and he only leaves his studio to meet Van Laere. Sometimes he goes to see his family or to play a game of tennis. It’s a monotonous life from which he escapes by building models of his imagination in his studio.

If he fails in his mission, Van de Velde will travel statically, like the characters in Max Ophuls’ Letter from an Unknown, sitting aboard a staid wagon while landscapes drawn on rollers undulate along the “train windows.” In his workshop, Van de Velde invents landscapes, new planets, new horizons. Props complement his pastel drawings, sculptures are added, and everything is immortalized on film. In his new exhibition, he plays with different media and distinctive buttresses to create the interior/exterior kaleidoscope of his intertwined lives. When no train leaves, all you have to do is dream of the destination, according to Van de Velde.

Because for Van de Velde, the risk is to lose desire. When a desire is fulfilled, it disappears. It is therefore a question of playing with it, of fanning it without frustrating it, of responding to it differently in order to keep the flame alive. In his film, like Cadet-Roussel, Van de Velde has three dream houses: in the first, he sleeps, surrounded by clothes hanging on drying racks —a strange banality. By metro, he reaches the second, where he meets Van Laere around a tennis court. To attain the third, a swimming pool worthy of Hockney’s approval, Van de Velde crosses invented landscapes reproduced on his Canson papers.

In Van de Velde’s work there is this idea of eternal beginnings in search of a perfection never achieved — his is an enduring fragment of a day from a life. As athletes tirelessly repeat patterns in training, the artist seeks again and again to break down the barriers that separate reality from his imagination. In the gallery, everything is concrete, established: the sculpted houses are presented in the middle of the drawings, the film unites everything. But it is by following the artist’s journey that we can only truly create narrative continuity — something alive. A life projected in a thousand bursts of dreams on different media — even if it decomposes — must nevertheless be seen as a unified force. Each stage of a service is needed for the next, to pass along intent, trajectory, and energy. It is the interdependence of all these sequences that generates life. Through Van de Velde, lives overlap, intertwined. There is neither man nor artist to separate: there is only an avalanche of possibilities as powerful as an Opelka serve at the moment of impact.