Oleg Cassini

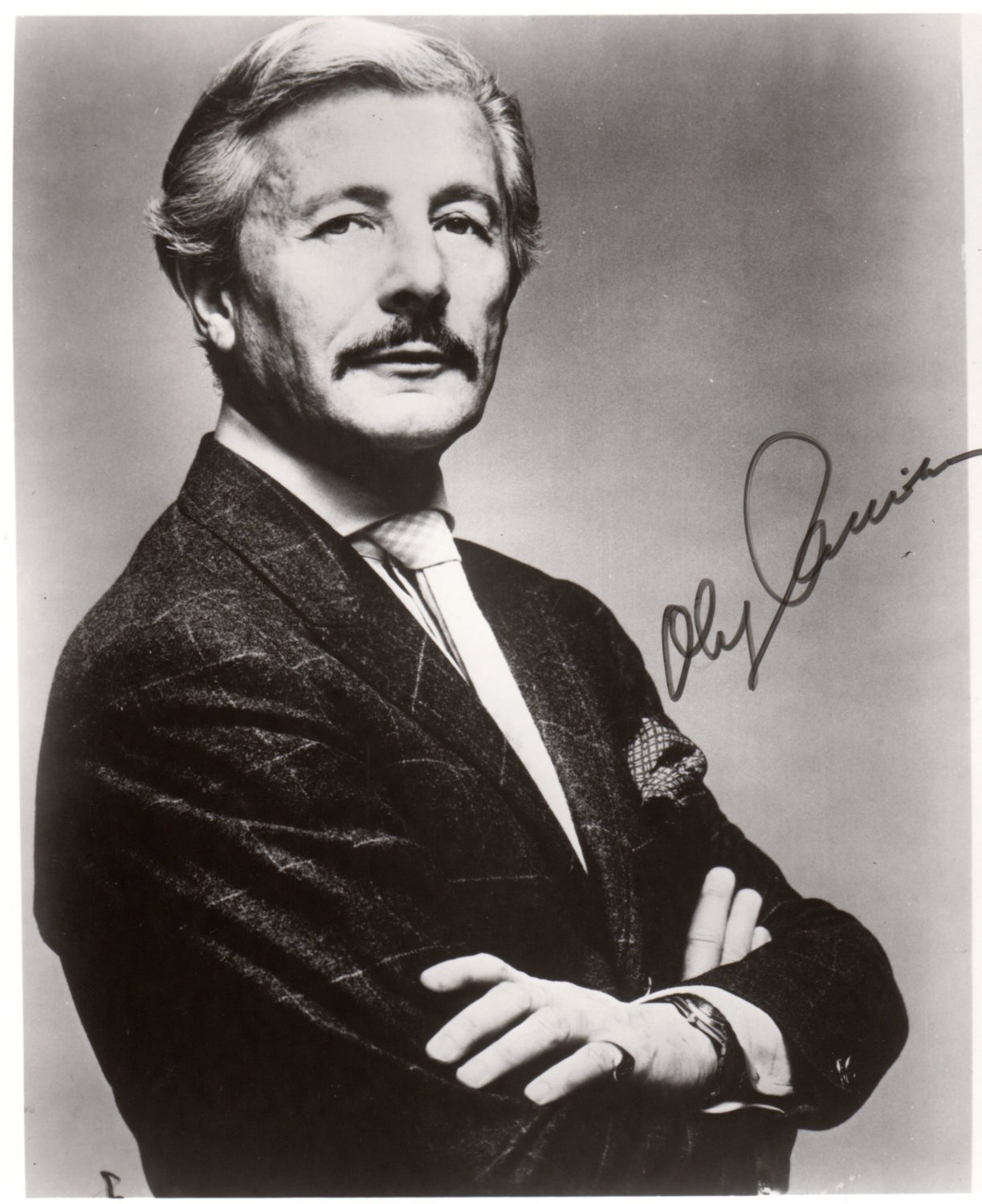

For most people, the name Oleg Cassini conjures a visual image. Even if we know nothing about the man, we picture him: the shock of wavy silver hair, the Clark Gable moustache, the aviator sunglasses, the broad shoulders and trim, military physique. Someone named Oleg Cassini could not have looked otherwise.

And if, in fact, we do know more about who he was—either because we are of the older generation or because, if younger, we are an aficionado of everything having to do with either Jackie Kennedy or Grace Kelly—what we are likely to know is that he was a clothing designer and a party boy, a bon vivant with a very particular style. But few people realize that he was also a champion tennis player. Moreover, in the 1970’s, Cassini was the creator of a line of tennis wear that brandished the bold colors of the avant-garde painting of the era. In 2004 when he was age ninety-one and he was interviewed for The New York Times, his answer to a question as to why, with his reputation for pillbox hats and “red-carpet gold” evening gowns, he was launching a new line of clothes called Oleg Cassini Sport, part of his answer included the beloved rubric, “Tennis, anyone?”

The only other person who has ever had a name that makes one imagine a Russian Czar as an Italian was his younger brother Igor Cassini. Their names, however, were a bit of a construction. Oleg had, in 1913, been born in Paris as Oleg Aleksandrovich Loiewski, Igor, born in Sebastopol in 1915, was Igor Aleksandrovich Loiewski. Their mother was, until she was married, Countess Marguerite Cassini; their father was Count Alexander Loiewski.

Oleg would write of his own birth, “The doctor arrived in a carriage after midnight. He wore a top hat, white tie and tails, white gloves, and spats … I arrived … at 2:00 a. m., an hour that became one of my favorites in later life.”1 In his lively memoirs, Cassini makes it sound as if he remembered the sight from having witnessed it and not because he was told about it later in life when memory becomes conscious. Cassini’s confidence in his right to amusement was genetic. The reason for being in Paris was clear: “My father was employed, at the time, in the pursuit of pleasure; that was his occupation.” The count “practically lived at Charvet”—the elegant Parisian shirtmaker—and “owned several hundred shirts, all of them silk in various colors … He would send these shirts, fifty at a time, to London for laundering. He also claimed to own 552 ties.”2

The colors of the count’s silk shirts would have an impact on Oleg’s designs for tennis clothes.

There were diplomats on both sides of the family. In 1917, the Russian Revolution forced the Loiewski family to flee Russia and leave their lavish homes and substantial fortune behind. Oleg’s cousin Uri was shot in the Kronstadt Revolt just before his family escaped, first to Denmark, then Switzerland. They were on their way to Greece at the invitation of its Royal Family when revolution started there also; the Loiewskis got off the train in Florence, where they settled, which was when the boys began to use their mother’s maiden name as their surname.

Marguerite Cassini started a successful fashion house in Florence and had a roster of international clients, among them many Americans. The boys, meanwhile, grew up in easy circumstances, and Oleg proved himself to be a natural athlete, appearing like a seasoned horseman from the first moment he got into the saddle, as well as, at age fourteen, a talented costume designer. He won prizes for the Russian garb executed for him by a seamstress and worn by him and his brother, and sketched dresses that his mother included in her latest collection. “She said that I had the ability to understand a dress in one glance,” he would remember.3

Still, Oleg Cassini had certain struggles. Skinny and short for his age, with a big nose that made strangers call him Pinocchio, he wanted to appeal to women, but struggled. “I realized that I was starting with certain physical disadvantages and would have to work harder than other boys to succeed. My fantasy was to do this through athletics, to be a champion tennis player.”4 Watching his first tennis match on a summer holiday in Deauville, he was moved “by the innate elegance of the sport, the formal dress, the graceful movements.”5 This eventually led to “a frantic program of tennis practice.”6

At sixteen, Cassini watched his American girlfriend, Baby Chalmers, play tennis on a court in a pine forest in Forte dei Marmi. Then she and he watched a tournament in Viareggio. “I remembered the feelings I’d had about tennis at Deauville; it was simply the most elegant sport. I had to be a tennis player.”7 He told his mother this was his ambition. She bought him and Igor tennis racquets and hired a German instructor for them, but in truth, we taught ourselves. We played every day for hours. We threw ourselves into it, and were playing tournaments within a year. Mother was very pleased. She’d say, ‘With a tennis racquet and a dinner jacket, you’ll be able to go anywhere in life.’

Oleg had a ranking at the club, and, before long, he was playing tennis and was an Italian junior champion.

The Cassinis’ way of life soon fell apart, however. Following the stock market crash, Countess Cassini’s business began to fail, and then it collapsed completely. “We continued to appear to be rich, and to appear so for all the world,” but the family was forced to sell its villas, and Countess Cassini told her sons they would have to manage without her support. Yet their mother continued to instill optimism in them.

We were still gentlemen, she insisted. Still Cassinis. The absence of money was only a temporary inconvenience.8

Oleg and Igor were to carry on as before, and “playing tennis was very important in that respect.” Oleg continued to practice the sport, and to flourish at it. What became an anchor in his adolescence would prove to be one forever after. “My ability with a tennis racquet opened many doors throughout my life. Wherever I traveled, all I had to do was find the best club, introduce myself as a ranked player, and then prove it on the court, and I’d be welcomed as an equal.”9

Even though Cassini was on the Italian junior Davis Cup team and was “ranked among the top ten in Italy”—immodest about his skills in his memoirs, he does not specify if this was on a junior level or for players of all age—he was inconsistent as a tennis player. He tended to do badly in morning matches, which he attributed to his “social proclivities.”10 But then he would be surprisingly victorious in difficult matches. He “won thirteen major tournaments,” in many of which he was considered the underdog. Referring to the way he played not just as a teenager but from them on, Cassini would analyze his own game,

My strengths as a player were speed and guile, willpower more than strength. I played tennis in fact as I lived; I ran and ran. I ran my opponents silly. I ran myself silly.11

The way that he ran on the tennis court was parallel, he believed, to the speed with which he did everything else in life, physically and metaphorically.

Cassini also played soccer on an important teenage team. At the University of Florence, he was on the ski, track, and equestrian teams, and managed to find the time to study political science when he wasn’t practicing one sport or another or chasing ladies. He attended the Accademia di Belle Arti Firenze, studying under the great metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico, and then went to Paris to study fashion under Jean Patou, the French couturier who had designed tennis clothes for Suzanne Lenglen. Cassini made a painting on silver foil of a vibrantly colored evening dress which won him a prize, and he went on to start a boutique in Rome where his clients included the cream of the crop of Roman society and the film industry.

He also got himself into a duel over a young inamorata. He won it simply by nicking his opponent, and developed a reputation as a knight-like womanizer, about which he was characteristically pleased with himself.

News of this duel spread through Italy overnight, and it did wonders for my reputation.

So I was known to the young women of Italy. I was a curiosity: a gentleman who fought duels, played tournaments tennis, was called “the Matchstick” because of his temper, and also designed ladies’ clothes.12

In 1936, Cassini sailed for America, where, he later wrote, his possessions were in keeping with his mother’s advice, “limited to a tuxedo, two tennis rackets, a title, and talent.”

It was a bit of an exaggeration, but his skill at tennis quickly got Cassini into two important “West Side Tennis Clubs” where his life would change. The first was on the East Coast, in Forest Hills, New York, and the second on the West Coast, in Hollywood, California.

Cassini arrived in New York at the end of 1936. He initially lived in a YMCA and attempted unsuccessfully to get work as a designer. His brother Igor then appeared and had with him a jeweled miniature of Nicholas II that the Czar himself had given to their maternal grandfather. It had originally been incrusted with diamonds, but their mother had had to remove and sell most of them in Europe to manage after her business collapsed. Still, there were enough jewels remaining on the miniature for the Cassini brothers to be able to sell it for $500, and they lived off the money.

Oleg and Igor soon went to the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills and introduced themselves as ranking Italian players; they did so well in their first doubles match that they were invited to become junior members. “This was our only link to the glamorous world we assumed was our natural habitat. Given our dreary reality at that point, there was an almost dreamlike quality to our immediate acceptance on a tennis court.”13 That summer, Oleg did well in small tournaments all over New England; room and board was provided to the players. In the autumn, he began having greater success as a clothing designer as well as a man about town, frequenting the Stork Club and El Morocco and starting a firm he named “Oleg, Inc.”

Next, he headed to Hollywood. Wendy Barrie, an attractive actress who was the girlfriend of the gangster Bugsy Siegel, invited him to the West Side Tennis Club in Cheviot Hills. Tennis again gave Cassini entrée into a world that he would not have known otherwise. Film directors, actors, and agents all played at this West Side Tennis Club; on one of his first times there, Cassini spotted Errol Flynn and Gilbert Roland on the courts, and sensed that his skills with his racquet might get him into the film world. But he knew that he was not yet in the top echelon—that real status was being invited to a private court, like Jack Warner’s—while those who hung out at the club over the weekends were mostly unemployed the way he was.

One of the other people without a job was the future agent Ray Stark, “a very energetic tennis player” who “was called ‘Rabbit’ because he scurried about.”14 They had good games, and Cassini was quickly noticed as such a good player that he “was welcomed as an equal”15 and invited for a month of free membership. His not having to pay was a good thing; by then, Cassini was so broke that he had to sell his car. He knew that he would not survive in Hollywood without one—“it was like being lost in the desert without a camel”16—but none of his efforts to make it as a clothing or costume designer had succeeded, and he would not take an ordinary job that would prohibit his getting out on the tennis court whenever he wanted.

The day he sold his car, Oleg Cassini was asked into a Round Robin tournament. “You have to play with real hackers, and it’s not good for your game,” but he had nothing better to do. He was paired with “a gray-haired, distinguished-looking gentleman, a nice fellow and a fair weekend player.” Cassini was so good that they got into the finals and won.

His partner was thrilled beyond belief. The amiable man, about whom Cassini knew nothing except for his first name, had never won in a tournament, and so he invited Cassini home for a celebratory drink and to meet his wife. He had a high position at Paramount; they happened to be looking for someone in their costume department where the only other designer was the renowned Edith Head. Cassini’s doubles partner knew that chances were slim at best of his getting the job, for which it would be necessary to produce sketches for a Claudette Colbert movie before the following morning at 10 a.m., but he still encouraged Cassini to try with the same spirit and acuity that he demonstrated when volleying at net.

Cassini and Ray Stark rushed to Paramount at the end of that momentous Sunday afternoon. There Cassini was told that the job was to replace Omar Khayam, a well-known costume designer, and that not only were there thirteen designs required before the deadline, but that there were many other submissions already. Cassini indeed worked the same way that he played tennis. Ray Stark delivered the drawings on time, Cassini got the job (for $250 a week) and was told to report immediately, and his life was changed forever. He credited it to his having won that Round Robin.

Cassini was soon doing the clothing for Veronica Lake, Gene Tierney, and Rita Hayworth; eventually he would also dress Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn, Joan Crawford, Anita Ekburg, and Gina Lollobrigida. When World War II broke out, he volunteered for military service, and ended up as a First Lieutenant for five years in the U.S. Cavalry. He returned to Hollywood afterwards, but in 1952 moved to New York to set up a fashion house. The Oleg Cassini Collection flourished immediately.

Igor Cassini, meanwhile, had become a gossip columnist, the second one to write under the name of Cholly Knickerbocker. In 1947, using that pseudonym, Igor had named Jacqueline Bouvier “deb of the year.” In 1953, just before she married John Kennedy, Oleg met her. In 1961, soon after she became First Lady, Mrs. Kennedy made him her official couturier; he got referred to as “Secretary of Style.” As he began to fashion “the Jackie look,” Cassini said, “We are on the threshold of a new American elegance thanks to Mrs. Kennedy’s beauty, naturalness, understatement, exposure and symbolism.” Consciously dressing her as both a film star and a queen, he put her in designs of timeless simplicity, very much in the style of French haute couture. Mrs. Kennedy’s brother-in-law, Senator Edward Kennedy, eventually said, “Oleg Cassini’s remarkable talent helped Jackie and the New Frontier get off to a magnificent start. Their historic collaboration gave us memorable changes in fashion, and style classics that remain timeless to this day.”17

Cassini, meanwhile, had been getting married or engaged to marry at the same remarkable pace with which he did everything else. After he divorced his first wife, Merry Fahrney, he married Gene Tierney, divorced her, and got together with her again. He subsequently became engaged to marry Grace Kelly, and ended up marrying Marianne Nestor, whose face was known from the covers of fashion magazines, and who would end up surviving him.

In 2004, at age ninety-one, Oleg Cassini was asked, in a New York Times interview, if he ever considered being a professional athlete instead of a designer. He replied,

At the very beginning of my career, when I opened my business in Italy, I was also a ranked tennis player. I had won many tournaments. To be an athlete was my first choice. Second choice: designer. However! There was more money in being a designer at that time. The athletes were not making the money they make today. I’m talking about 1933.18

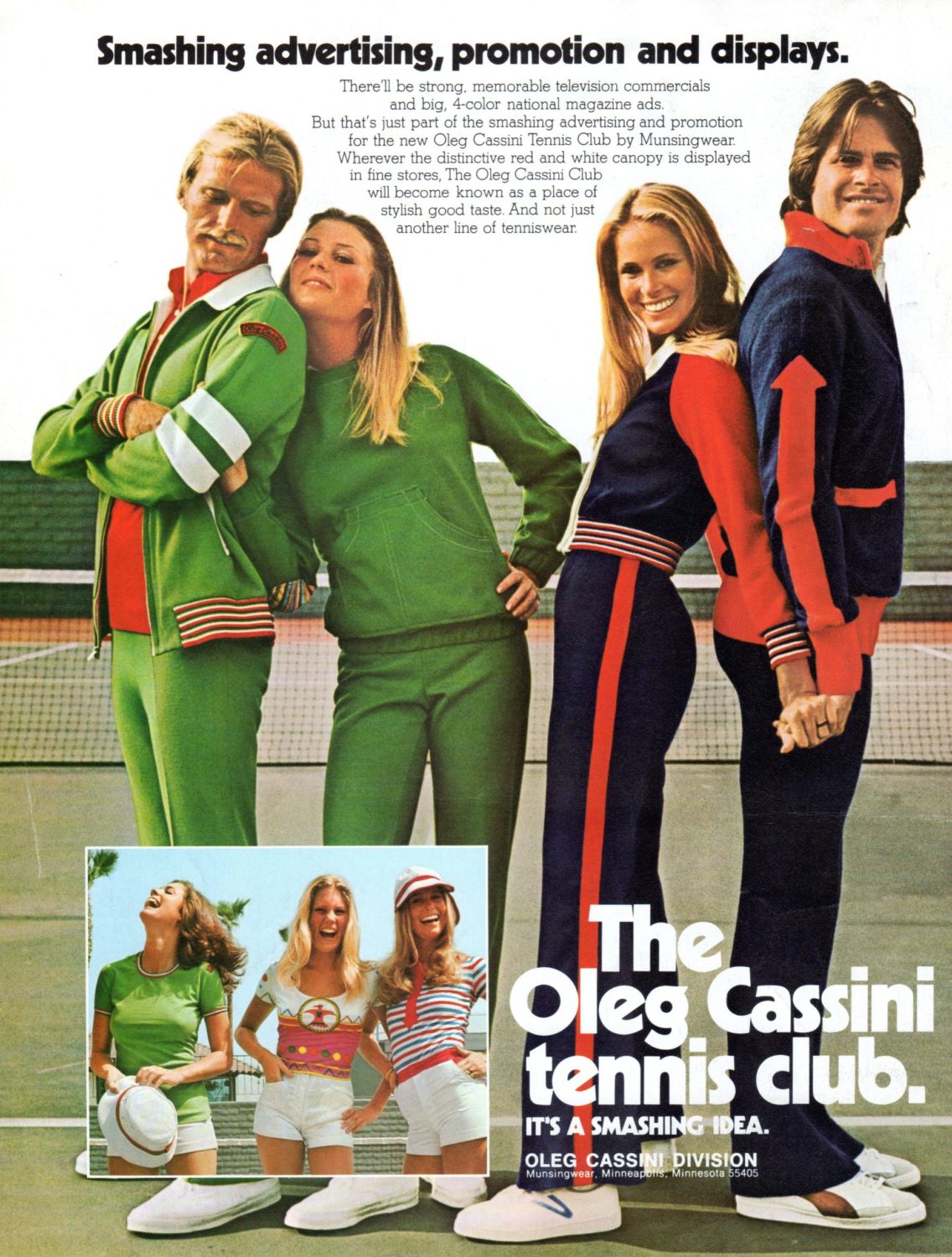

But he had combined sports and fashion successfully. He launched, in the early 1970s, the “Competitors” Collection of menswear. His advertising featured Ted Turner in his sailing clothes, Bob Hope in his golf wear, Michael Jordan for basketball, Mario Andretti for racing, and Charlton Heston, Regis Philbin, and Kenny Rogers for tennis. The clothing became immensely popular in each domain. Among other things, Cassini outfitted the entire Davis Cup team.

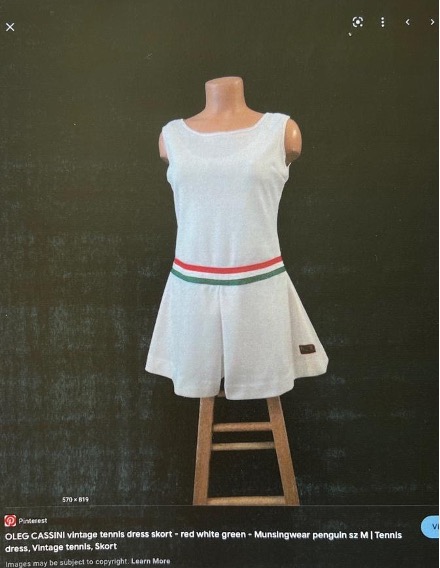

His tennis clothes were unlike no one else’s, a declaration of flash and modernity. The colors jump out at you; the emerald green, Coca-Cola red, and royal blue could not be stronger. In style, they were the antithesis of the elegant whites worn in the pre-Revolutionary Russian where Cassini came from, but in their joyous assertiveness, the unabashed sense of pleasure that infuse objects by Fabergé, they belong there. The warmup jackets resemble the costumes of drum majorettes; the trousers, especially those with bold stripes up the sides, would suit soldiers guarding the palace. There are also polka dot tennis dresses; even a plain white dress has colorful red and green stripes on it. One jacket has a design motif clearly reflecting Cassini’s fondness for American Indian designs.

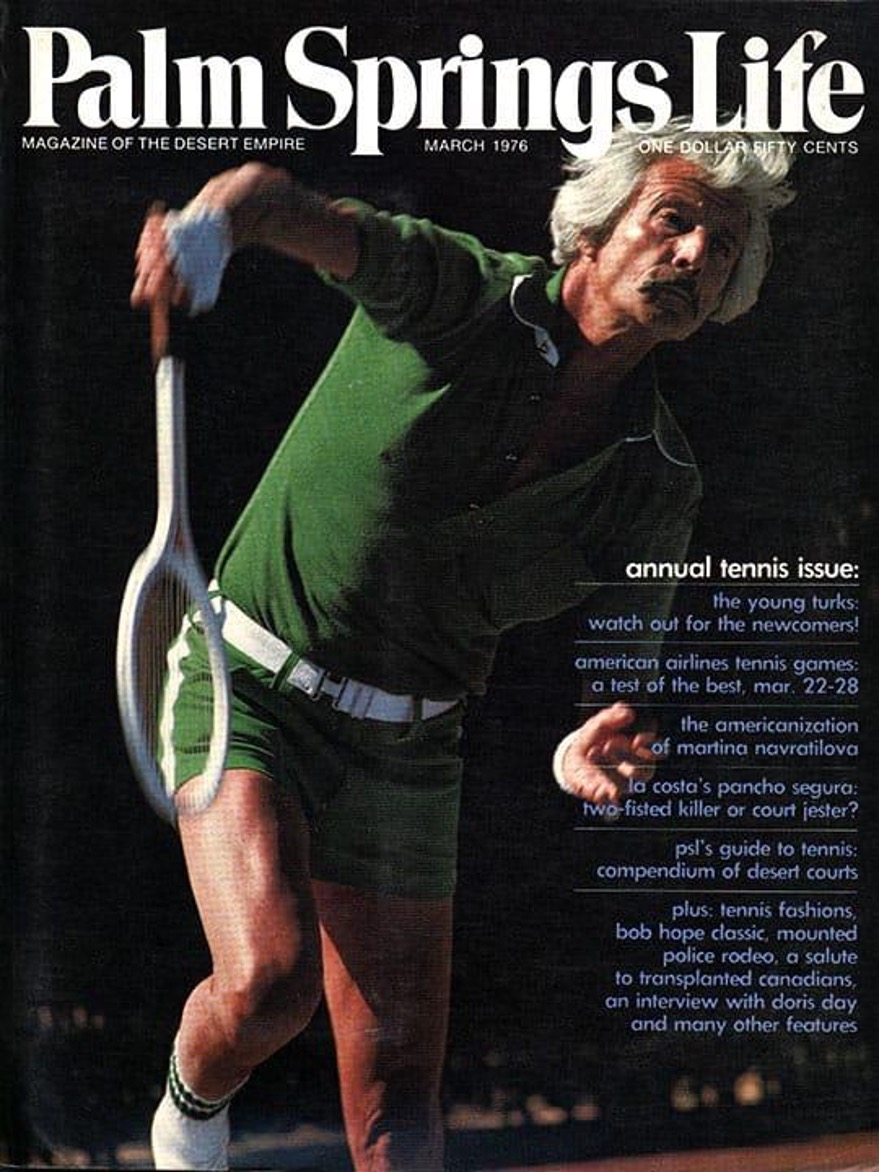

At just about the time that Cassini brought out his tennis clothes, a writer identified as a psychiatrist at Colombia University wrote a cover story for Time Magazine entitled “Sex & Tennis.” He referred to Cassini’s new line, “ ‘Ninety percent of the men who play tennis with women,’ says Designer Oleg Cassini, who has lately branched into alluring multicolored outfits for tennis players, ‘do so with some hope of sexual reward.’ ”19 Seductiveness was clearly what he had in mind when he designed the number in which he appeared on the cover of Palm Springs Life. For this magazine which has a fairly limited readership, he wore what appears to be one piece, clinging, in his trademark green, with a white cloth belt as part of it.

Oleg Cassini referred to the period in which he designed tennis clothes as “the height of the tennis boom.” He played in pro-celebrity tournaments when he was in his mid-sixties, and, in 1976, triumphed in what was a high point for this man who loved good sport and glamorous people. The event was the Robert F. Kennedy Tournament, hosted by Ethel Kennedy a few years after Robert Kennedy was assassinated. A benefit for the RFK Memorial Foundation, it began with a party at the Rainbow Room, that lavish and cheerful space at the top of New York’s Rockefeller Center. In the course of that festive evening, partners were picked from out of a hat. The next morning, whether or not people had hangovers or were tired from dancing into the wee small hours of the morning, came the all-day event, which was intense, and very serious. Oleg Cassini won it that year with a pro named Jaime Fillol. He was proud as punch to be congratulated in front of some twenty thousand people and ranks of television cameras by Ethel Kennedy, Governor Hugh Carey, Jacqueline Onassis, and Howard Cosell.

Oleg Cassini’s mother had been right. He had worn his evening clothes the night before, and now, tennis racquet in hand, he had reached a pinnacle of earthly existence.

Article publié dans COURTS n° 13, automne 2022.

1 Oleg Cassini, In My Own Fashion, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987, p. 16.

2 Cassini, ibid., p. 16.

3-4 Cassini, p. 35.

5 Cassini, pp. 35-36.

6 Cassini, p. 36.

7 Ibid., p. 45.

8-10 Ibid., p. 46.

11 Cassini, pp.46-47.

12 Cassini, p. 54.

13 Cassini, p. 77.

14-15 Cassini, p. 104.

16 Cassini, p. 105.

17 1995, Rizzoli. p. 224.

18 Amy Larocca, “The Sporting Life,” The New York Times, May 28, 2004,

19 Time Magazine, “Sex & Tennis,” September 6, 1976. Vol. 108 No. 10.