Is Wimbledon’s all-white dress code here to stay?

In the beginning, white wasn’t a rule for players at Wimbledon, but a fashion and a tradition. Until that fashion and tradition became a rule, 85 years after the very first Championships.

There are three fun facts about Wimbledon’s all-white rule. Firstly, that from the first Championships in 1877 until as late as 1962, players were allowed to wear other colours, despite white being the favourite. Secondly, unlike the other slams where the dress code has relaxed over the years, Wimbledon’s has become stricter over time (with 2 exceptions: 2012 and 2023 – more on this below). And thirdly, since its introduction in 1962, Wimbledon’s all-white rule has only had 4 significant revisions in its lifetime. Looking through its chronology, it appears that three of the four revisions were instigated by rebellious acts!

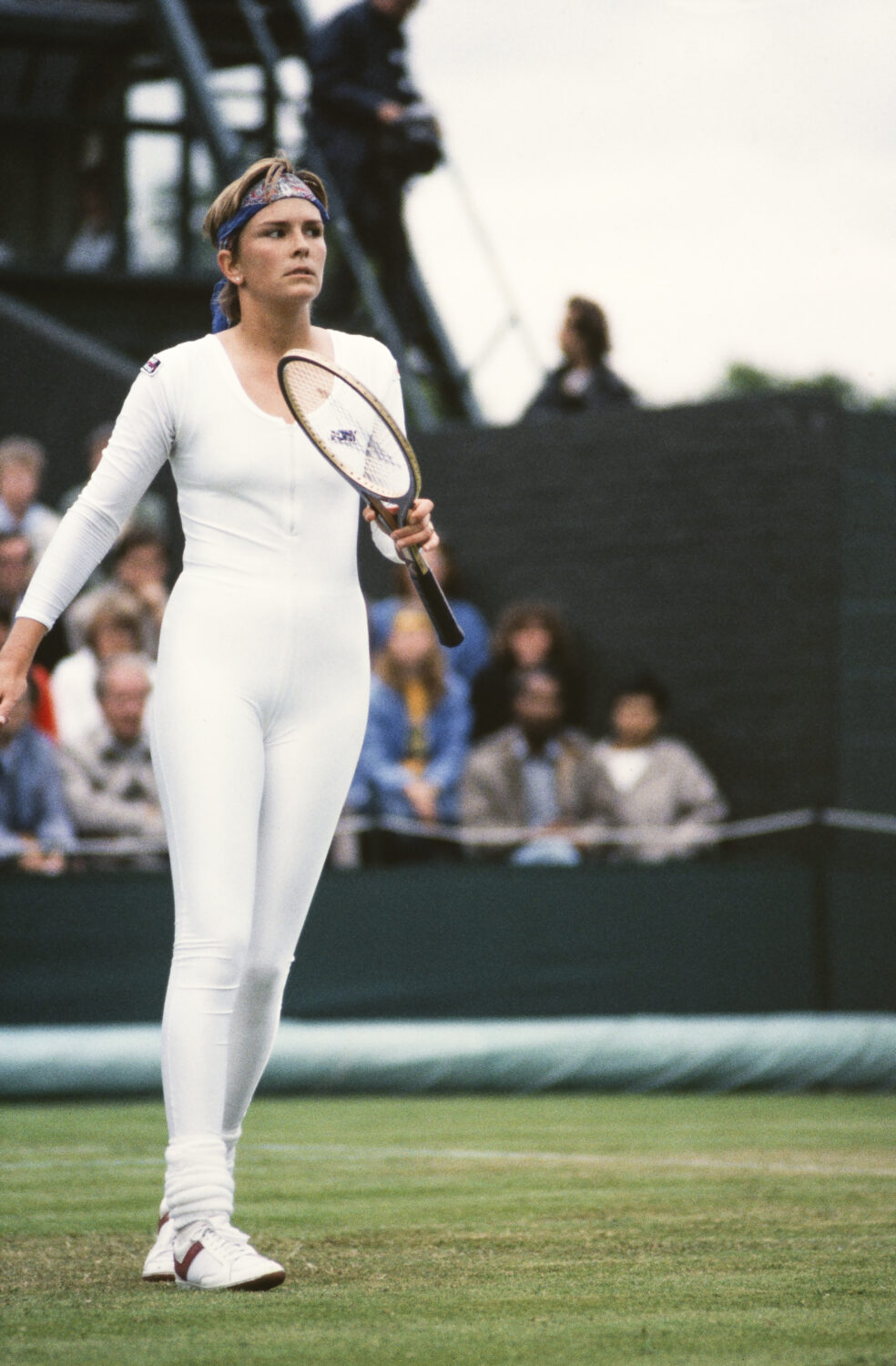

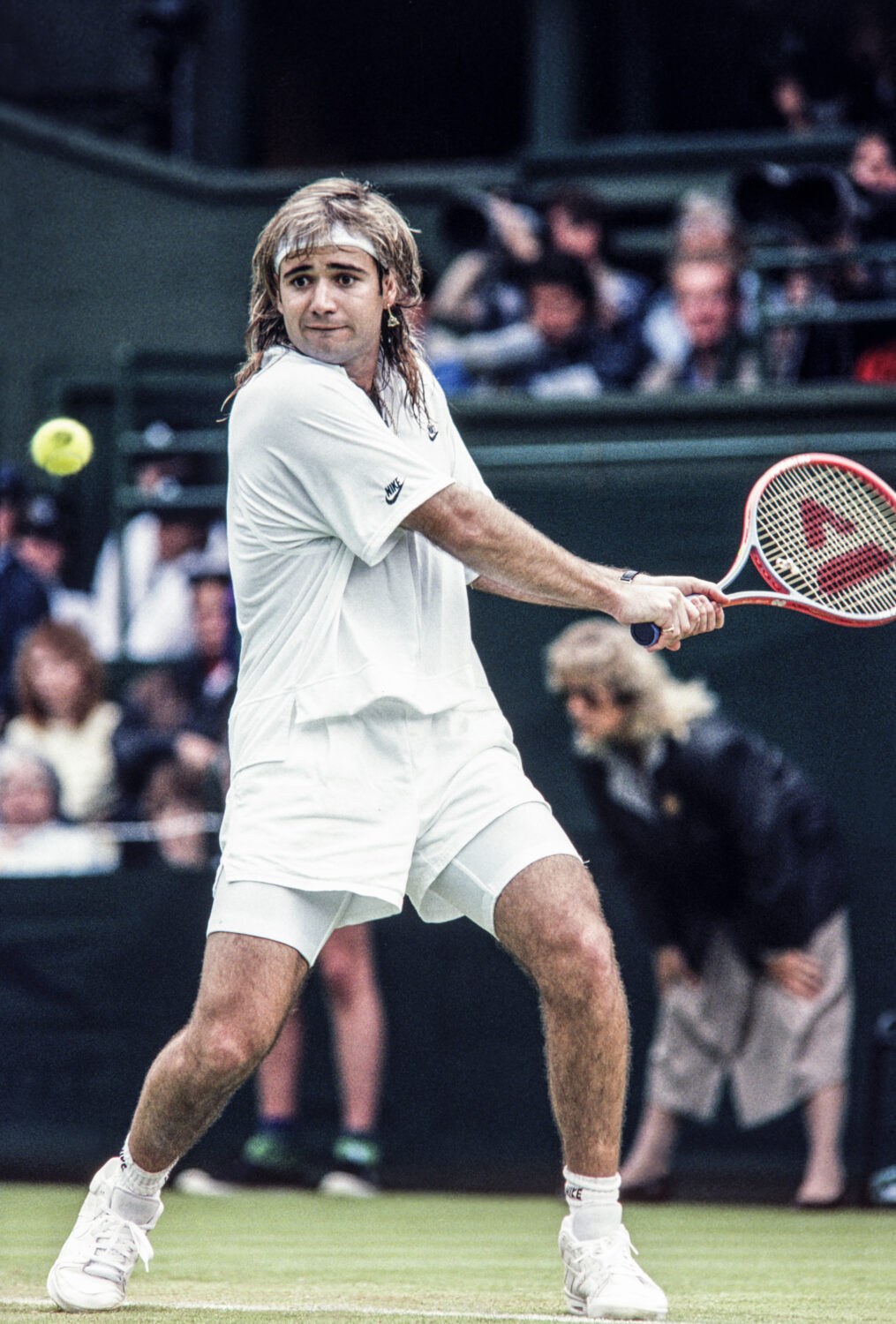

Whilst Wimbledon has had many fashion rebels flouting its all-white rule over the years (Anne White being asked to change out of her catsuit in 1985, Venus Williams being asked to change her pink bra mid-match in 2017, or Nick Kyrgios being fined for wearing a red cap during the final trophy presentation in 2022, to name but a few), four players appear to have made enough of an impact to instigate change. These were Maria Bueno in 1962, Andre Agassi in the 1990’s, and in 2013, a combination of Serena Williams, and wait for it, the debonair King of Grass himself – Roger Federer!

But let’s put it into perspective: Wimbledon remains the only slam with an all-white rule. The US Open also had an all-white rule until 1972, when it became the first international event to permit coloured tennis clothing. The other 2 slams, Australian Open and the French Open in comparison have always been more relaxed. Being the only slam with a dress code harking back to the 1880s, was bound to ruffle a few feathers along its course, by some who felt the rule was unnecessarily draconian, and behind the times.

But to understand the reason for the all-white rule, is to understand aesthetics, fashion history, the class system and world events happening outside of tennis at the time. Above all, tradition.

Cue the Victorians, and their attitude to sweat. Or ‘perspiration’, as they preferred to call it. Sweat stains for Victorian women were unsightly and unladylike. As fashion historian Valerie Warren explains, Victorian women “were under immense social pressure to appear attractive, tidy and unruffled at all times”.I Sweating, having tanned skin or freckles were also characteristics associated with those that worked outside for a living – the labouring working class. As white clothing masked sweat stains, and deflected the heat from the sun, white was the favoured sportswear colour. Tennis quickly gained popularity amongst Victorian women, as it was the first sport to include men and women competitions. It is no wonder that tennis fast became the rage – it provided a rare opportunity for the wealthy to engage and socialise with the opposite sex. Tennis was Tinder for the Victorians – forget swiping right, the swipe of a beautiful backhand dressed in pristine white was enough to attract the desired attention! It was about looking one’s unruffled best.

The dresses that graced Wimbledon’s Centre Court in the Victorian period were a white version of garden party outfits: full length with high necks, long sleeves, petticoats, corsets, hats, and in some cases, even carrying parasols whilst playing, to avoid the dreaded tan. Some wore aprons to avoid soiling their white clothing, and to store tennis balls in the pockets. By comparison, men had it easier. They wore cream or white trousers and shirts, often with coloured sash belts and ties. Sometimes, even cricket clothing was acceptable on court.

Yet even then, white had still not been imposed at Wimbledon. It was practical, traditional, and then fashionable, thanks to fashionista and 1884 Wimbledon Ladies’ Champion, Maud Watson.

Fashion Designer and Art Historian Diane Elisabeth Poirier explores this in her book Tennis Fashion: “white was by no means the rule: the fashion for tennis whites was launched by Maud Watson”.II Watson’s all-white outfit was an elaborate ankle length two-piece consisting of draperies accessorised with black stockings and black shoes. This pretty much summed up the Wimbledon look, until a life-changing event with catastrophic consequences shook the world: war.

The First World War began 28 days after Wimbledon 1914, on 28th July, changing the world and its attitudes towards women, who took up roles and jobs previously only occupied by men. Warren says this was pivotal: “Against this background it was the dramatic appearance at Wimbledon in 1919 of a daring and brilliant young Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen, which was to provide the focal point of the attack upon the restraints of tradition”III

Enter Suzanne Lenglen – the trailblazer who revolutionised the way women dressed, played and lived. Her balletic style and flamboyance, both on and off court, made headlines, making her the superstar of the 1920’s. She drew crowds thanks to her unique style of play, her behaviour (boosted by sips of cognac at the changeovers!), and the way she dressed. Lenglen’s arrival at Wimbledon couldn’t be more illustrative of the changing of the guard. Unlike her counterparts, Lenglen dared to expose skin, opting for style and function. She arrived ‘scandalously’ bearing her legs in a white calf-length pleated skirt, thanks to French couturier Jean Patou, who we can thank for introducing the pleated skirt to tennis! Patou’s tennis designs had a profound influence over couture houses Chanel, Lanvin, Schiaparelli and Hermès, who started to feature tennis style in their collections. Thanks to Coco Chanel in the 1930’s, tanned skin became fashionable, and reflective of expensive holidays on the Côte d’Azur. Women players swapped stockings for socks, making tennis clothes more comfortable.

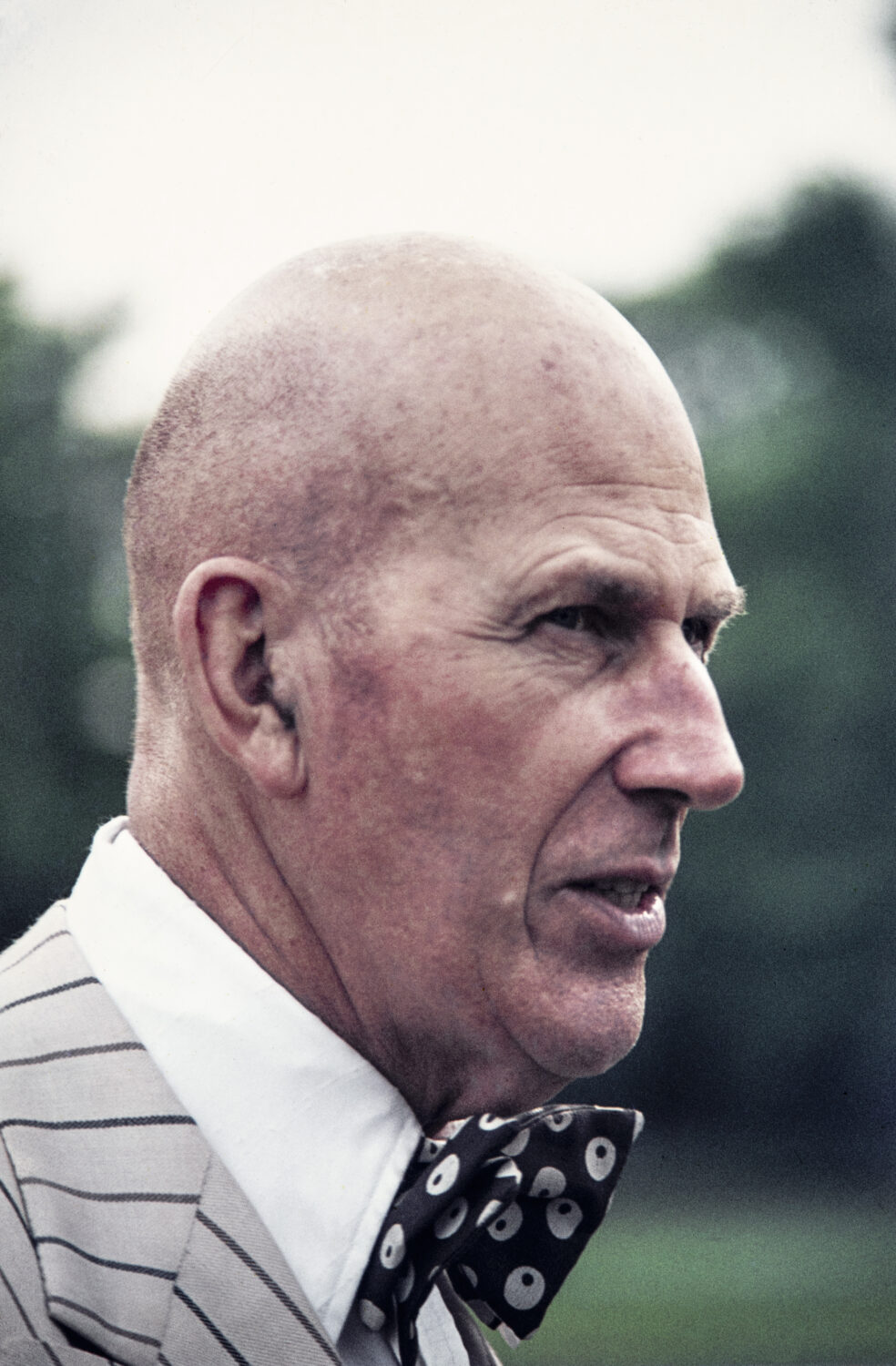

But it was Lenglen’s friendship with British couturier, Ted Tinling that turned the tide for women’s fashion at Wimbledon. In his autobiography, Tinling explains: “Suzanne had convinced me that most spectators like to see touches of colour added to white on a tennis court”.IV His glamorous eye for design was transformative for women’s tennis wear. He formed close friendships with the women he designed for, creating some of the most showstopping pieces in tennis fashion history. No discussion on tennis fashion is complete without acknowledging Tinling’s legacy.

Over the years, Tinling had worn many hats: player, umpire, player liaison, and even spy! But his biggest impact and legacy was through fashion design. His creativity often overstepped the boundaries of what was considered acceptable tennis wear, as he experimented by adding flourishes of colour and design to white dresses. One such outfit resulted in a ban from the Championships for 33 years, and from his job as player liaison. The short dress was designed in 1949, for Gussie Moran. The showstopper, and shock factor came from the lace-trimmed underwear that accessorised the dress.

Whilst the ban enabled Tinling to flourish as a fashion designer, he reached his nadir in 1962 according to Wimbledon, with his white dress for Maria Bueno, with a shocking pink lining. This was enough for the Wimbledon management committee to make the all-white rule official for the first time in its history, when the ‘Predominantly White’ rule was introduced, to be imposed from the 1963 Wimbledon Championships.

Wimbledon’s action certainly didn’t go down well with Tinling. In his autobiography, White Ladies, Tinling’s frustration with the new dress code is palpable, describing it as illogical and behind-the-times, given the progression to colour in other aspects of life since the 1950’s, such as colour television and coloured newspapers: “If tennis fashion was to keep a respected place in the new picture it must not become an enclave of Victorian inhibition in a fast-moving world attuned to colour… for fifteen years I had made it my mission to keep tennis fashion abreast of the times. Here was a roadblock of outdated thinking and I found it a regrettably backward step”v. His frustration was echoed by others over the years, particularly Andre Agassi, almost 30 years later, when his disgruntlement led to him skipping Wimbledon altogether – for 3 years!

Agassi’s look and Wimbledon were initially not a match made in tennis heaven. He brought a whole new aesthetic to the court with a maximalist look that personified, yet also transcended the 1980s. Bringing rockstar vibes, Agassi sported big hair, gold jewellery, flashy neon colours, and bold prints – from his headband down to his neon ‘hot lava’ Nike sneakers. And who can forget those iconic stonewashed denim shorts with neon lycra undershorts (surely a re-release is on the cards)? In other words, ‘not very Wimbledon’. Yet for Agassi, image was everything (the tagline was featured in a Canon tv commercial). He ended up boycotting Wimbledon for 3 years (1988 – 1990), after his very first appearance in 1987, in defiance of the ‘Predominantly White’ rule. In his autobiography Open, he reveals his initial dislike of Wimbledon: “I resent rules, but especially arbitrary rules. Why must I wear white? I don’t want to wear white. What should it matter to these people what I wear?”

Thankfully, Agassi eventually had a change of heart. When he announced his return to Wimbledon in 1991, rumours were abuzz as to whether the tennis rockstar would defy the Wimbledon dress code. In the weeks leading up to The Championships, media speculation dominated headlines around what he would wear before he’d even stepped on court. So, when Agassi took those first strides on Centre Court for this first match, he drew gasps and applause from an eagerly awaiting stadium, delighted at his new-found reverence for Wimbledon. He arrived dressed head-to-toe in a pristine white tracksuit, dramatically removing it to reveal more pristine white underneath. Almost as if to apologise for his absence and pay homage to the cathedral of tennis, the colourful showman’s all white outfit evoked rejuvenation and freshness. The rebel had returned as an example, and Wimbledon loved him for it.

Agassi’s refreshed appearance and the jubilant reaction to it clearly made an impression on the Wimbledon Committee, perhaps sowing the seed for an updated dress code, 4 years’ later. In 1995 the ‘Almost Entirely White’ rule replaced the ‘Predominantly White’ rule, which continued to limit the amount of colour and size of logos. Looking through Wimbledon outfits from the 80’s and 90’s leading up to the 1995 rule, you can see why this was imminent. Colours and patterns had begun to take over the white. Think Lendl’s Adidas 1987 ‘the face’ polo shirt – featuring a wavy red/blue/white cat’s face, or Sampras’s Sergio Tacchini polo shirt with purple and blue diamond pattern horizontally across the chest for this 1993 Wimbledon, and matching purple/blue stripe design on the shoulders, or Steffi Graf’s Adidas colourful print on the left of her polo shirt in 1993. If the all-white tradition was to continue, a reset was required.

But only one year was the exception to the rule. For those curious about how Wimbledon would look if there was no all-white rule, look no further than the 2012 London Olympics. Centre Court is unrecognisable, surrounded by colourful Olympics branding/advertising, and players wearing colours. Joanne Simons, Professional Tennis Manager at the All England Club informed meVI that this was an exception, given that the Olympics are a multi-sport event, and athletes wear their national colours to represent their country.

Even the greatest are not immune to punishment for flouting the all-white rule at Wimbledon. That includes the ‘Greatest of All Time’.

In fact, it was two GOATS that prompted a refresh of the ‘Almost Entirely White’ rule in 2014, after they graced Centre Court with a bright orange accent to their 2013 Wimbledon outfits. Defending Champion Roger Federer arrived on Centre Court for his first round match against Victor Hanescu, looking as immaculate as ever, with one orange accoutrement: orange pimpled soles on his white Nike sneakers. Wimbledon acted promptly, as Federer changed the shoes for the rest of the tournament, with no flash of orange to be seen again. Serena Williams was also feeling the orange vibe that year, as she wore bright orange undershorts, causing much controversy as to whether this adhered to the dress code. She certainly wasn’t the first to do it, Tatiana Golovin wore red undershorts with her white dress at Wimbledon 2007, also causing a media storm.

2014 brought us the strictest version of the all-white dress code in Wimbledon’s history, as the ‘Almost Entirely White’ rule was extended to include shoes, visible underwear and accessories such as caps and wristbands, and specification of the shade of white (that is, not off-white or cream). Additionally, specification around a “1cm coloured trim” around the neckline/cuffs, outside seam of shorts, skirts and tracksuit bottoms.

In the 9 years that ensued, the all-white rule was challenged specifically regarding underwear colour. Many players felt this was one detail too much, with women feeling uncomfortable at having to conform to wearing white underwear, and at being checked by Wimbledon officials that they adhered. Caroline Wozniaki was quoted at the time as saying that the checks would be “creepy”,VII with similar sentiments expressed by Barbora Strycova, Pat Cash, and Venus Williams amongst others. Yet white underwear remained mandatory until as late as 2023, when the much awaited change finally came.

2023 saw the fourth and latest revision to the all-white rule. Unlike the previous revisions, this one was political, and reflective of equality, diversity and inclusion, marking a significant step for women. Female players had expressed anxiety about wearing white whilst menstruating in addition to the anxiety of their performance. It was about freedom and practicality, and Wimbledon not only listened, but also sought advice to get it right. The Wimbledon Committee of Management engaged with the WTA, clothing manufacturers and medical teams around how best to support women and girls competing at The Championships. As a result, the all-white clothing rule was updated to allow women to wear mid/dark-coloured undershorts if they choose to. Whilst all other requirements on other clothing, accessories and equipment remain unchanged. This was Wimbledon showing us that whilst tradition is very much a part of its ethos, it is also forward-thinking.

Simons also informed me that Wimbledon’s all-white rule is very much a collaborative process. It is reviewed carefully each year, with the help of clothing and shoe manufacturers, plus feedback from players to “hear if there are particular challenges arising from their perspectives. It’s very much a dialogue; we listen to their comments, and they also understand the importance of maintaining the white clothing rules for our brand. Many of them say they enjoy the challenge and also the clarity we now have in the rules; there’s less room for ambiguity and that leads to greater consistency in how we can apply the rules. For example, a few years ago we removed the requirement for the back of any top or dress to be completely white, because we felt this was now unnecessarily restrictive, and the manufacturers really welcomed the change. More recently, we amended the rule to allow female competitors to wear coloured undershorts, which was very much influenced by conversations with the WTA and several manufacturers around how we could alleviate anxieties for the players, while still upholding the spirit of the white clothing rule. In the end, it was a really easy decision to make.”

When I asked Simons why the all-white rule is still so important for Wimbledon, she confirmed that “That unique feature is really important to us to maintain as it dates back to the origins of the sport when they first played in all-white to conceal sweat. It’s also part of the guidelines of the All England Club year round, not just for the tournament”.

The all-white is part of Wimbledon’s DNA, as emblematic and individual for the most famous tennis tournament in the world, as are its strawberries and cream, or the grass that The Championships are played on. Together with all-green backdrop without overt advertising, the all-white brings focus to the tennis. Unlike at other slams, where the experience is multi-sensory with blinking billboards, advertising, pumping music between points, etc, Wimbledon’s aesthetic brings calm and focus. Crucially, having all competitors wear one colour makes the tournament egalitarian. On its website, Wimbledon states: “To us, the all-white rule isn’t about fashion, it’s about letting the players and the tennis stand out. Everyone who steps on a Wimbledon court, from a reigning champion through to qualifier does so wearing white. That’s a great leveller. If a player wants to get noticed, they must do so through their play. That’s a tradition we’re proud of.”VIII

It’s been 61 years since Wimbledon implemented the all-white rule. Today, the rule not only applies to competitors, but also to members of the All England Lawn Tennis Club, and their guests. If Ted Tinling was alive today, perhaps he would be surprised to learn that this fashion and tradition has not only stood the test of time but has become stricter than in his day (albeit more collaborative).

Wimbledon states that, “One reason Wimbledon insists on white clothing is tradition. Lawn tennis was predominantly played in white clothing from the game’s beginning in the latter part of the 19th century”.IX Whilst the Victorians started the fashion which became a rule, one key ingredient has kept the all-white rule very much alive. The same ingredient that sets Wimbledon apart from any other slam: Tradition. And this wonderful tradition isn’t going anywhere soon.

With special thanks to Dr. Anna Boonstra, Stephanie Edwards, Joanne Simons, Sarah Frandsen and Robert McNicol, AELTC, Wimbledon

I Warren, Valerie, Tennis Fashions: over 125 years of Costume Change (the Kenneth Ritchie Wimbledon Library, Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum, Church Road, Wimbledon) 2002

II Poirier, Diane Elisabeth, Tennis Fashion, pg. 10 (Assouline, 2003)

III Warren, Valerie, Tennis Fashions: over 125 years of Costume Change (the Kenneth Ritchie Wimbledon Library, Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum, Church Road, Wimbledon) 2002,Pgs 12, 13

IV Tinling, Ted, White Ladies, page 36 (Stanley Paul, 1963)

V Tinling, Ted, White Ladies, page 28 (Stanley Paul, 1963)

VI Simons, J (2024) Online interview for Courts Magazine by Amisha Savani

VII Sanderson, David, ‘Women object to knicker checks’, The Times, 28 June 2014