“If you don’t understand what helps your game thrive,

you’re going to struggle”

When Ons Jabeur struck the winning shot of her opening 2021 French Open match versus Yulia Putinstseva—a calculated cross-court backhand following a drop shot that drew her opponent to the net—she fist-pumped the air in celebration, and trotted over to the net for the customary well-played-too-bad before her mind switched over to the next opponent.

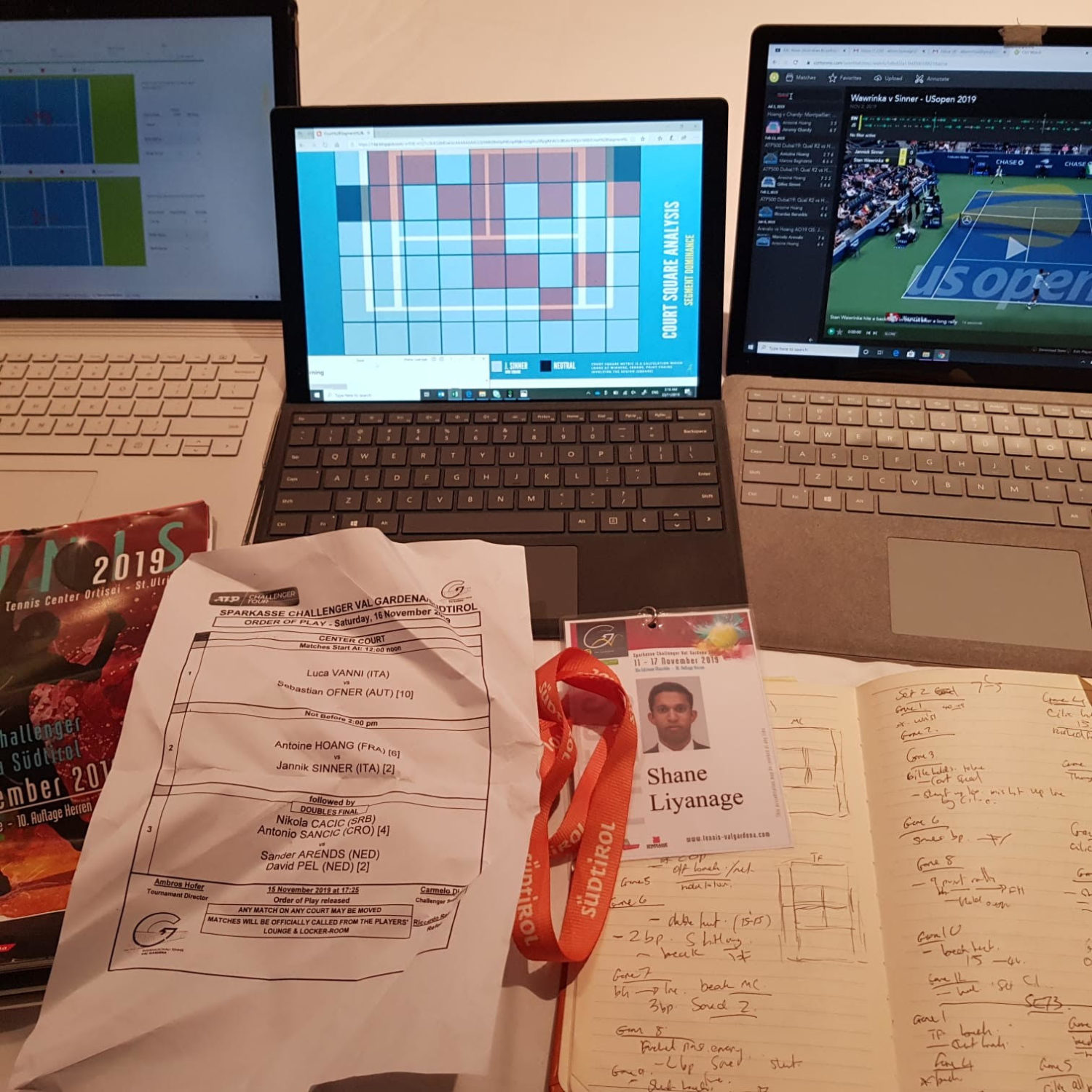

Shane Liyanage, in front of his computer 10,000 miles away, allowed himself a brief, satisfied smile and did the same. He loaded up the draw on his computer and scanned the list for Jabeur’s next opponent. He looked her up in his database—a directory filled with thousands of matches categorised by surface, players, and tournament details—looking for encounters with his player, or in the absence of those, matches they might have played against opponents with similar characteristics.

He would spend the next few hours preparing a scouting report and a selection of video clips before a Zoom call with Jabeur’s coach.

“You’ve got to focus on the match ahead of you. It’s about being ready when you need to be,” Liyanage says.

Shane Liyanage is the founder and principal consultant of Data Driven Sports Analytics (DDSA)—a sports intelligence company providing professional tennis players and their coaches with data.

Much like army intelligence support troops on the ground with reconnaissance and intel, Liyanage uses his skills as a data analyst along with his expansive knowledge of the sport to supply his players with weapons to employ on the court. Six of Liyanage’s players have made it into this year’s French Open, and with such busy clients as Aryna Sabalenka, Alberto Ramos Viñolas, Ons Jabeur, and Emil Ruusuvuori, he barely has the time to enjoy tennis himself.

“I grew up loving the sport,” Liyanage says. “Now that I’m working in it, I probably don’t watch random matches. I don’t enjoy it as much.”

Over the course of his professional career, Liyanage has spent so much time analysing and dissecting matches that his attitude to tennis and the way he observes even the most casual of matches has changed. “I’m always thinking, ‘Okay, if I was helping this team, how can I do it? What would I do in this situation?’ Or if I’m playing against them, ‘How can I use that?’ I think that’s kind of my mindset.”

The services Liyanage and his company provide vary from client to client. Some come to him for the analysis of their game, a breakdown of areas that the scientific approach indicates they need to work on, be it elements of their game or particular play patterns. Others rely on his scouting help—being able to identify chinks in their opponents’ armour prone to ruthless and calculated exploitation.

The analytical lens through which Liyanage sees a tennis match stems in part from his professional approach, but the way he perceives the game—the manner in which he breaks it down in his head into elements—was present from an early age.

“I played tennis as a junior at the Australian Money Tour level, but I was never very talented. I was probably the least talented player in every match I played so I was always in the mindset that I had to do more. Whenever I played, I’d do a little bit of research—whether it’s talking to an opponent that had played that player or seeing if I can get my hands on a video. It helped me prepare,” Liyanage remembers.

Stepping out into the real world, as he puts it himself, Liyanage graduated as a lawyer with a background in commerce, statistics, and accounting. He was always drawn to the world of data and number-crunching, and after a while pivoted to data analysis, obtaining an executive data science specialisation certification and studying to get a Masters in Sports Analysis, before he went on to spend time with such sporting organisations as Cricket Australia. Around the same time, Liyanage started his own consulting company, initially working with ITF and Australian Pro Tour level players.

The big break came in 2019 when Federico Placidilli, Thomas Fabbiano’s coach, chose to use Liyanage’s services. “He was the first ATP player to give me an opportunity at that level. I really have to thank Federico for that, and Thomas for being open to using stats,” Liyanage says.

During a stellar 2019 season, Fabbiano enjoyed high-profile wins over Stefanos Tsitsipas at Wimbledon and Dominic Thiem at the US Open. “That was probably what put me on the map a little bit. Other coaches took a little bit more notice of what I was doing after that,” Liyanage says.

While the word of mouth certainly does the work in elevating his status as the man to-go-to for data insight, Liyanage believes that his services speak for themselves. “At certain events, I’d go to coaches and say, ‘Look, I’ll do a couple of rounds for free showing you my services and then you can make a decision.’ I’ve ended up working with clients that way.”

While sports data analysis continues to gain popularity in professional athlete circles, it has been largely hidden from the public eye—it’s the elaborate clockwork-like mechanism that turns potentially tricky encounters into comfortable wins. “It’s been booming a little bit more recently. There have been some great analysts, almost pioneers, that had done this for maybe a decade, but the adoption rate was very low from players,” Liyanage explains.

“It was always this nice-to-have thing. But in the last five to six years, some of the top players have become a bit more vocal about it, saying that they’re using it, and that’s given the platform for more people like myself to pitch our work.”

“When you see the guys at the top doing it and enjoying success, you follow in their footprints. The lower-ranked players started thinking, ‘Maybe I need it, maybe it’s something that is as essential as a trainer or a physio,’” Liyanage says.

“I’d say that now, most of the top-20 are either using it or their Federations are providing them with the data. Players ranked in the 50s to 100s have certainly started adopting it a lot more in the last 12 months. I think that the COVID break allowed people to look at different ways to explore their game and one of those areas was data. I’ve noticed a bigger uptake.”

Liyanage is set up from home and most of his work is done remotely. Occasionally, he joins the player’s entourage, but even then, he does much of the strategic heavy lifting from the relative obscurity of his hotel room. For a time in 2019, Liyanage formed part of Thomas Fabbiano’s entourage, travelling with the player to the French Open, and later in the year to a Challenger event in Helsinki. While the tournament yielded a moderate result for Fabbiano, Liyanage was able to connect with a number of Finnish players and coaches. Although it took another two years, the connection eventually led to his work with Emil Ruusuvuori.

Ruusuvuori, 22 and currently ranked 74 in the world, is one of the more exciting prospects on the ATP Tour. At this moment in his professional life, he has entered the ‘polishing’ stage of his career—the biomechanics of his game are already irremovably embedded into his body. What Ruusuvuori now needs is a different kind of approach than, say, Alberto Ramos Viñolas, also one of Liyanage’s players. Viñolas, who has been around the Tour for much longer, not only knows his game back to front but is also born and bred on clay. For a tournament such as Roland Garros, there are very few changes to Viñolas’s game that Liyanage will point out—the main focus of his work will be on scouting opponents his coach has not had the chance to see.

Ruusuvuori, on the other hand, hails from Finland, where he spent most of his formative years playing indoor hard court tournaments. Despite having spent time at the Rafa Nadal Academy in Manacor, a boot camp for clay court grinders, playing on clay is still fairly foreign to him. For Ruusuvuori, Liyanage’s approach will be focused more on long term gains, trying to point out patterns and plays that data suggests will work for him.

“A really good coach once told me he’s got an 80/20 rule: it’s 80% about your player and 20% about the opponent,” Liyanage says. “If you don’t understand what helps your game thrive, you’re going to struggle—you’re not going to have a plan out there.”

In so many words, this could be DDSA’s motto—it sums up the reason for the company’s existence and the challenges it aims to tackle.

“The first thing is having a look at what areas work well for you, what are your strengths, because that’s what you want to maximise. Then we look at areas that are ‘uncomfortable’ for the player—whether it’s the court position, a particular shot, or a particular match situation that puts you under pressure—and work out how to get out of them,” Liyanage explains.

A lot of the heavy lifting is done by the in house deep-learning AI tracking tool, but Liyanage, determined to uncover every little detail that could be translated into giving his player an edge, pours over hours of tennis footage with an additional video tagging tool and an old-fashioned notepad and a pen.

“It’s about the success you’re having on a shot, but also about what shot you’re getting back, how often are you getting forehands,” Liyanage says. “Shot sequence is also a big one. I look at sequences and try to come up with metrics for a specific player based on different parts of the court. If you’re getting the ball in your backhand corner and you’re a couple of metres inside the baseline, what are the best options for you? What are you likely to win the point with? That’s a key thing to look at.”

In his analysis, Liyanage uses a combined approach of blanket strategies that, as data would suggest, a player must have, and personalised ones designed to maximise the player’s strengths and minimise their weaknesses.

“For example, the second serve and the second serve return points are directly correlated with success for everyone. But then there are some tailored ones as well that I won’t mention because they’re specific to the player and I don’t want to give too much away. But for Ons Jabeur, for instance, we’ve got specific metrics, KPIs, that she needs to achieve to do well.”

Liyanage divides his work into three main categories based on the available time. “During a tournament, particularly at the non-Grand Slam events when you’re playing the next day, and the timeframes are short, you often try to give the coach whatever you can. It has to be a quick turnaround, and it has to be something that can be easily actioned. I call it low latency,” Liyanage explains.

“After a tournament, you might have two, three weeks when a player is sitting out, and they’ve got time to focus on things. You’d give them information on things that they can work on in that space of time.”

“And then finally, you’ve got the off-season from the start of November, until mid-December, or maybe even early January. It’s a bigger period of time and the focus is on some of those longer-term things that you might want to work on, like a technique change.”

The data analysis attempts to encompass the players’ game in its entirety—from strategy to technique to physical and even mental aspects. “In tennis, most of the time, you’re not hitting a ball. I did some analysis with a junior around their behaviour in between points. I’d look at whether they’d remonstrate or had a negative attitude, and then I’d have a look at what happens on the next few points,” Liyanage elaborates.

While the advanced, AI-based technology is able to come up with the most optimal changes in a player’s technique and strategy, it’s the analyst’s job to make sure that the athlete buys into them.

Although most communication with the player happens through the coach, Liyanage is aware of his blind spots, and remedies them by surrounding himself with a team that complement his skillset. Living in the world of data, things that are obvious to him may not always be communicable enough for the athlete to take on board.

Because of that, Liyanage’s circle includes ex-players and high-performance coaches. “I will run some ideas past them, and they might go, ‘You know, that’s really hard to understand for a coach who hasn’t really been exposed to data.’ So, I will refine it,” Liyanage says.

Liyanage started working with Ons Jabeur in early 2020. Before her hamstring injury at the Madrid Open, she had climbed the ranking from a position in the 80s to number 24 in the world. “A massive rise in the rankings,” Liyanage says with a smile. “And with Sabalenka, it’s such a huge thrill to work with someone ranked so highly.”

“A lot of people thought she couldn’t play on clay. To see her enjoy this success on clay—winning a big title in Madrid, being in the top five in the world—that’s something I’m really excited about.”