Break Point’s advantage has been to ace life back into tennis!

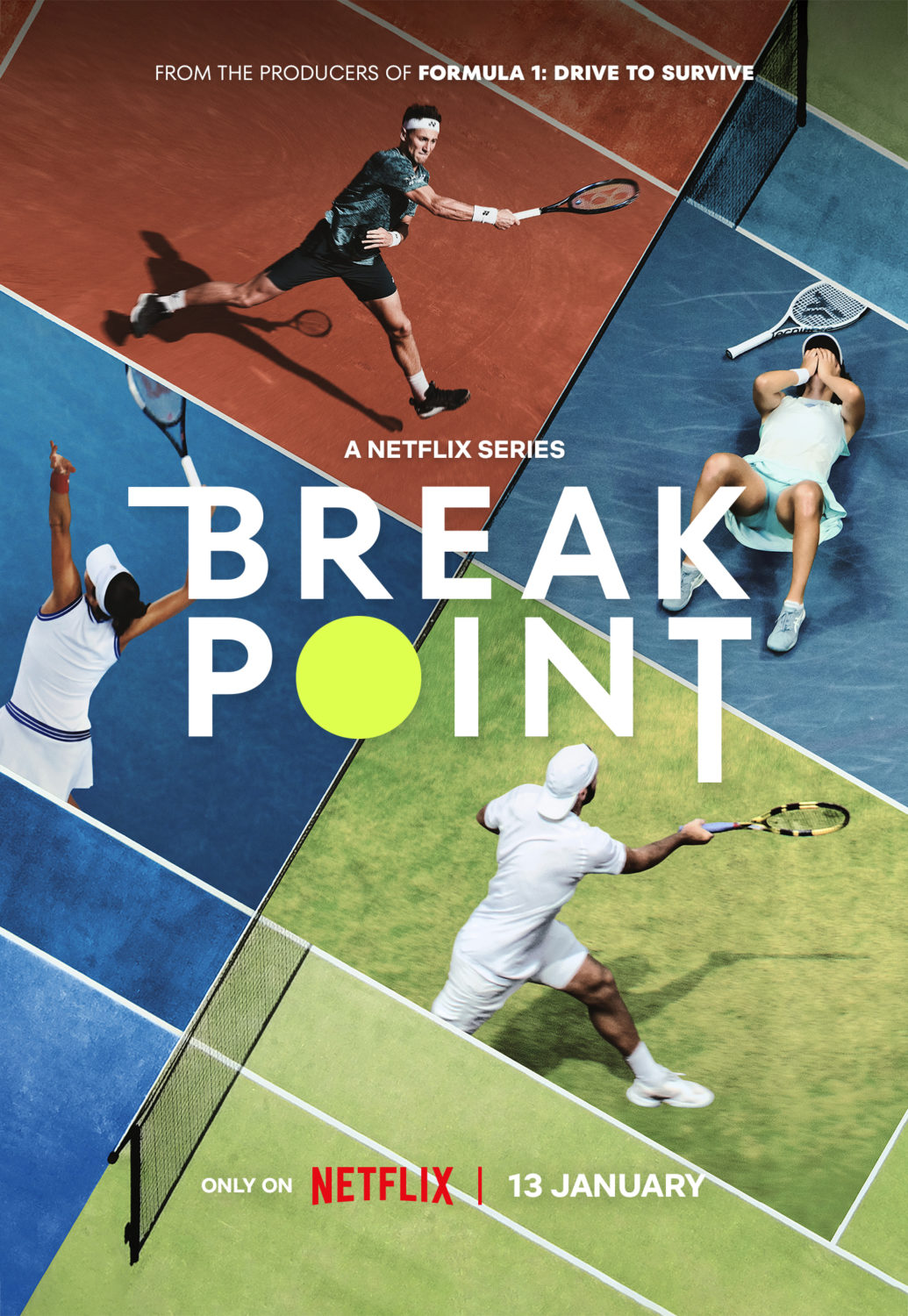

My adrenaline starts pumping. Yes, it’s about tennis. But I’m not on court, I have no racquet, and I’m armed simply with my laptop. I’m about to watch Break Point, an intimate fly-on-the-wall docuseries following a selection of tennis’s top professional players on and off court for a year. Thanks to Netflix and Organic Publicity, I have been granted exclusive preview access to the press screening, two weeks before worldwide release on 13th January 2023. I’m excited about what I’m about to watch because there has never quite been anything like it.

Break Point, by Box to Box Films, is made by the team behind Netflix’s F1: Drive to Survive. Whilst watching that, I found myself drawing parallels between Formula 1 and tennis: surely the same model of documentary could be applied to tennis, another sport where the athlete alone carries the burden of success or failure. Executive Producers Paul Martin and James Gay Rees reveal in the production notes, that the idea was borne out of a project discussed with Andre Agassi years ago. Although that project fell through, hearing about the physical and mental demands of the game made them want to show the world a side of tennis people didn’t know existed.

Has anything been done like this before? In 1981, the late, great photographer and filmmaker William Klein produced The French, an acclaimed tennis documentary film about the French Open. His behind the scenes access to players was enviable (think locker room chats whilst smoking a cigarette, filming under the net during match play, the list goes on). It was doubtful that anything like it would ever be replicated. But Break Point has somehow managed to penetrate the impenetrable, and to do it for much longer – a year’s cycle of tournaments. This is laudable. Today’s tennis players are notoriously private. Post-match press conferences, tv interviews, even Instagram posts are often formulaic, rehearsed, airbrushed, or curtailed to appease sponsors or agents. Sports psychologists and coaches encourage players to put on a poker face, to avoid showing opponents any weaknesses. So, I had low expectations.

Spoiler alert: look away now and read the rest later if you want to watch it first!

Break Point’s Midas touch is its ability to gain unprecedented access, shining a spectacularly honest spotlight on the tennis world. In the production notes, Martin reveals, “when the access is good, it allows you to be much more intimate in your storytelling. The process moved pretty quickly once we had the buy-in from ATP, WTA and the Slams”. Showrunner Kari Lia discloses that the challenge was not just to gain access, but to maintain it for a full year, “we made sure we took time to sit down with players and chat through why they’re letting the cameras in. Some players understood that right away and others needed to talk it through. In the end that process paid off, and we were even able to delve into deeper issues, like racism, mental health and sexism in sport”.

It would have been easy and tempting to produce a glamorous documentary about tennis. The filming locations are amongst the most beautiful countries in the world. But like the title itself, this documentary has shades of dark and light. As every tennis player yearns for an advantageous break point to turn their match around, the price of living in a pressure cooker environment of winning and losing can bring anyone to breaking point. Mental health is a running thread throughout, as players open up about the price they pay for this career.

There are 10 episodes, covering the 2022 season starting with the Australian Open and ending at the US Open. Episodes 1-5 will release globally on 13th January. Episodes 6-10 will release in June 2023.

Filming and interviews have taken place with players, ex-players, families, trainers, and coaches; within professional and personal environments including homes, hotel rooms, and locker rooms. There are family dinners, childhood home videos and photo albums. The most revealing insights emerge from these very personal moments, when a player candidly reveals their innermost anxieties about opponents or life in general, showing that none of them are superhuman.

The immersive scenes felt like I had inadvertently eavesdropped on an intimate moment or conversation. Executive Producers Paul Martin and James Gay-Rees have truly aced this one. At tournaments, player’s boxes have been mic’d up to reveal intriguing interactions between player and box. The production notes reveal that the series was filmed as though shooting wildlife, using RED cameras, filmed on a high frame rate with long lenses for closeups. The editing team visited Wimbledon’s Centre Court to experience the sounds, smells and angles, and bring that immersive experience to the series.

From the very first episode, it becomes apparent that this is a staggeringly stark portrayal of a less than perfect life. Nick Kyrgios opens up to girlfriend Costeen Hatzi and coach “Horse” about his daily struggle with alcohol, which began after he was suddenly catapulted to stardom after beating Rafa Nadal at Wimbledon, “my life was just kinda spiralling out of control, drinking every single night”. Horse tracked Kyrgios’s daily location on his phone, to ensure he was okay.

Kyrgios reveals why he plays less tournaments than anyone else of his ranking, “tennis is an extremely lonely sport. I think that’s what I struggle with most. I need to be with my family. I need to have my close circle around me” Costeen shares, “he’s not as crazy as everyone thinks he is”, which becomes apparent. When he’s not playing to anyone, he’s subdued, thoughtful, philosophical, and caring to those around him. One scene shows Kyrgios apologising to Costeen for being too sweaty, as he joins her on the bench after a court practice. Another shows him in a restaurant serving food to those around his table. But then, like an actor on cue, the familiar showman emerges during a first-round match against Liam Broady. Kyrgios orchestrates the home crowd with trick shots, interacting with them, turning them into a frenzy, being cocky with the umpire and confirming that, “in the heat of the battle, I’m two different people. Sometimes I do cross the line. That’s just my passion, that’s just my emotions. Millions of people watching you and you’re not playing your best. Would you not be frustrated and angry?”.

A scene with mum Norlaila sitting in his bedroom further humanizes Kyrgios. Holding one of his broken racquets, she reveals the unhappiness her son went through from an early age, caused by racism, expectation, and pressure. But there are lighter off-court moments, showing Kyrgios joking with lifelong friend and doubles partner Thanasi Kokkinakis. Their chemistry is palpable, as in his relationship with Costeen. They flirtatiously role play, both pretending to be strangers, “we do this all the time”. They are inseparable, to the point of video calling each other during one of his drugs tests, as he holds up a cup of his urine sample, Costeen responds, “euww don’t show me the pee!”.

Like every good story, there is romance. Break Point follows Matteo Berrettini and Ajla Tomljanovic as they practice together, debate about what movie to watch in their hotel room and manage conflicting schedules. They share personal photos of themselves as a couple, and details of how they met (he slid into her DMs on Instagram!). Their hotel room is a chaotic spectacle of clothes and belongings strewn across the room, with an unmade bed. At one point, upon returning to the room, Berrettini realises the mess, questioning who was the last to leave the room.

Tomljanovic is candid about the challenges of dating a fellow tennis player, “we both enjoy being there for each other but that doesn’t mean there aren’t challenges… It’s just really good when we’re both winning, let’s put it that way”. She loses her next match and is out of the Australian Open. As Berrettini is still in, they negotiate how he is going to have a much needed lie-in, if she must fulfil an interview commitment in their hotel room the next morning. Chris Evert stresses that tennis is not only lonely but requires each player to be self-centred. The camera follows an upset Tomljanovic down a tunnel to sit on the floor with her coach, telling him that she wanted to break all her racquets. The fluctuating emotions caused by losses and wins are captured incredibly well.

As the series progresses, the strain on players is compelling, but the reason to persevere is explained eloquently by Paula Badosa, “it’s a drug. This sport is a drug. Winning big titles, winning big matches, it’s very very addictive”. An example of resilience is in Episode 3, when Taylor Fritz sustains a serious foot injury during a practice session in Indian Wells. The injury happens before his final against his idol, Rafa Nadal. Against the advice of his team and doctors, he insists on playing, acknowledging the risk of not being able to play again. He wins, but at the price of his health.

It is evident throughout that Break Point’s production team has built deep trust amongst the usually-private players and made them feel relaxed and candid in front of cameras. The production notes explain that producers initially conducted audio-only interviews, without cameras which were used against video footage. Executive Producer Gay-Rees adds, “obviously we’d have liked to put cameras on tennis balls, but that technology hasn’t been delivered yet”.

No tennis documentary is worth its salt without addressing the issue of equality. It features in Episode 4, focusing on the debate about equal prize money and airtime for women. Patrick Mouratoglu highlights that players from wealthier countries are more likely to receive lucrative sponsorship deals than smaller countries without resource or investment. Enter Tunisia’s Ons Jabeur, a player who has risen despite a lack of resource and investment, and despite facing cultural barriers as an Arab and African woman. Jabeur and her fitness coach husband discuss how they overcame the challenges of working together as a couple, and the challenges of women athletes having to choose between having a family or career.

A pivotal moment is when Paula Badosa opens up about her struggle with depression. Much like Kyrgios, she attributes the depression to media pressure and expectation after winning the junior French Open. In one harrowing scene, she tells her team that there have been moments where she has wanted to die. The production notes reveal that there was a huge amount of trust built between the production team and Badosa’s team, in helping Badosa tell her story, without sensationalizing it. Lia shared with Badosa’s team, a personal experience of losing someone close to suicide.

The final episode features the ‘old guard’ Rafa Nadal, together with two young prodigies Felix Auger-Aliassime and Casper Ruud. We are reminded of Nadal’s intimidating dominance in some hilarious moments when the cameras focus on him psyching his opponents out via his energetic pre-match ritual in the hallway. Whilst it is a fitting way to end and a reflection of the status quo, it is also a reminder that we are at a pivotal period in tennis, and after Roger and Serena’s departures, a changing of the guard is imminent. Break Point has done what F1: Drive to Survive did for Formula 1: it has injected fire, personality, guts and glory back into the sport which craves fresh interest. What an opportune time to create this documentary.

At the time of writing this, there are no current plans for a future series. But I hope the producers will consider a series dedicated to the lower ranked players and the challenges they face on tour. This would complete the picture.

Break Point is very watchable. Afterall, tennis is the ultimate Shakespearean tragedy of the modern era. As Andre Agassi once so eloquently said: “It’s no accident, I think, that tennis uses the language of life. Advantage, service, fault, break, love, the basic elements of tennis are those of everyday existence, because every match is a life in miniature”. Above all, there is something hugely inspiring when watching a group of people who, despite facing daily failure and loss, somehow manage to find the perseverance, positivity and resilience to keep going. There is always hope.