Why Stefanos Tsitsipas?

By Marnie Abbou

Who is your favorite player? This is always the first question that occurs when I talk about tennis. I answer even though it doesn’t really matter to me. Roger Federer made everyone agree for a long time. Now that the has Maestro retired, a silence often follows the question. I always need a few seconds to be honest with myself. I could answer Novak Djokovic or Rafael Nadal, and no one would judge. However, I always end up saying Stefanos Tsitsipas – I can’t help it.

I always kept an eye on the French Open without being a huge tennis fan. The 2020 edition, which took place in October due to Covid-19, wasn’t an exception. I just started my senior year and hurried to come back from school every day to catch the last couple of hours. I ended up watching Dominic Thiem by pure chance. I remember being hypnotized by his one-handed backhand and his devastating forehand. I followed his remaining matches with a lot of passion – but there weren’t enough according to me. I went through a roller coaster during his thriller encounter against Hugo Gaston (6/4 6/4 5/7 3/6 6/3) before having to face a huge disappointment when he lost to Diego Schwartzmann in the next round (6/7 7/5 6/7 6/7 2/6).

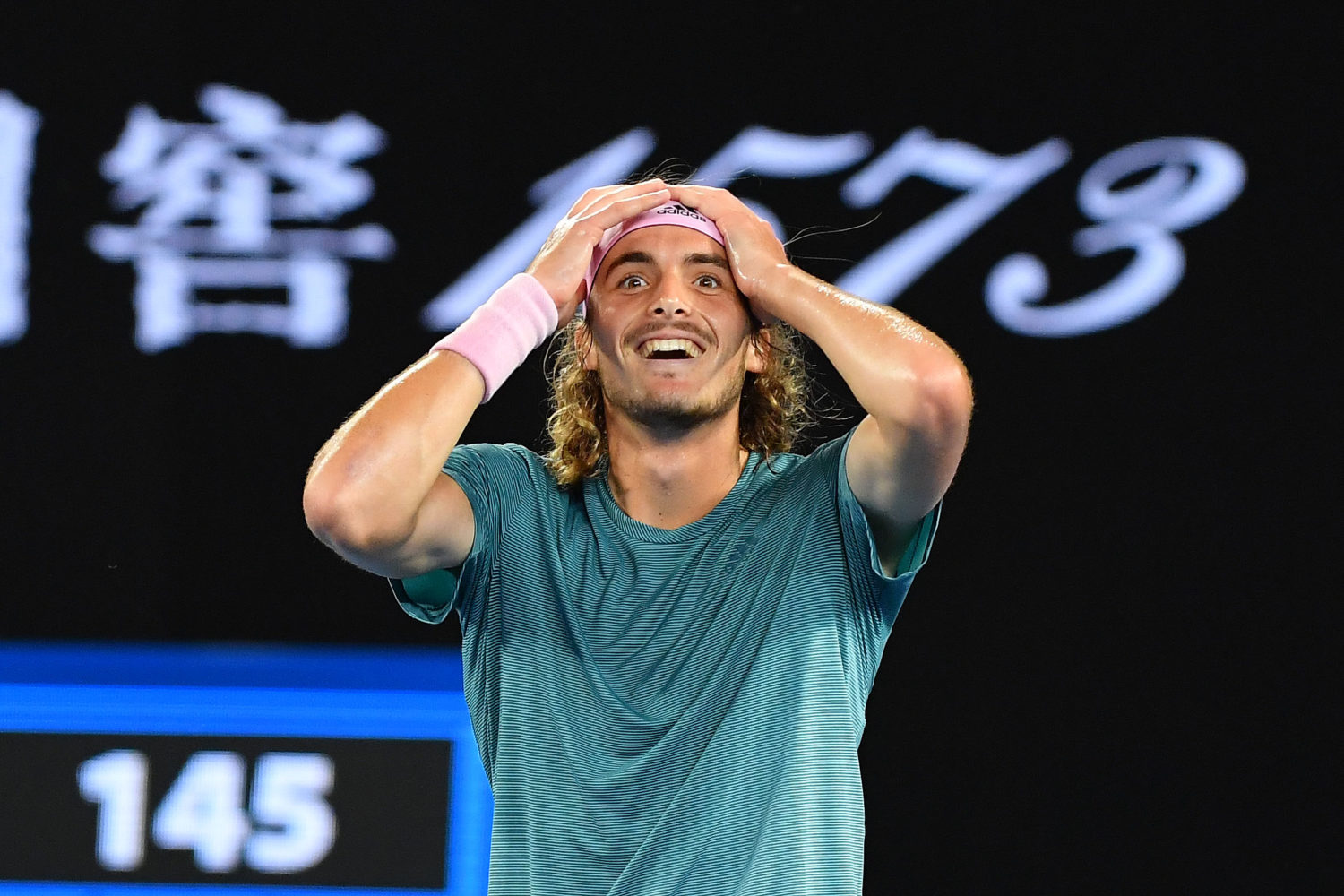

I thought that the French Open had lost its taste. I didn’t watch any match for a few days – until Friday night. I turned on the TV to kill my boredom. Stefanos Tsitsipas played Novak Djokokvic. The Greek, who I didn’t know then, was about to lose by two sets to love. I thought I would just watch the end of a platonic encounter before going to a family diner. I didn’t consider the ATP Finals champion’s fighting spirit. Stefanos Tsitsipas took me on a journey of several hours. All dressed in black, he made a string of slides on clay and ran after each of his opponent’s dropshots. While Novak Djokovic served for the match, he won a sixteen strikes rally by using his power on the forehand side. Astonished by the game of this unknown player and the suspense of the match, I couldn’t take my eyes off the TV. I decided to keep watching in the streets, in the subway and while eating (with my phone under the table). His loss (3/6 2/6 7/5 6/4 1/6) left me with a bitter taste in my mouth.

When the Philippe-Chatrier reopened its gates eight months later, the name of Stefanos Tsitsipas remained in my mind – as well as Dominic Thiem’s. The Austrian was defeated by Pablo Andujar (6/4 7/5 3/6 4/6 4/6) in the first round. I focused all my energy on Stefanos. I didn’t miss any of his matches. A class of philosophy? I watched his dazzling forehand accelerations from my phone that was hidden in my pencil case. A test the next morning? I learnt my history lesson while watching my new favorite player’s rises to the net. By chance – and with a lot of talent – Stefanos Tsitsipas reached his first Grand Slam final. I devoted my Sunday to it.

His match against Novak Djokovic had me in a tizzy. In a few hours, my enthusiasm transformed into a huge disappointment. His hidden dropshots and forehands down the line gave way to the Djoker’s indisputable domination. This loss (7/6 6/2 3/6 2/6 4/6) was even harder than the year before. It left me wanting more. How could I spend a year without watching a single match? I couldn’t. I dove into the ATP Calendar and discovered that I could watch tennis everyday if I wanted to. This simple fact changed a lot of things in my life.

I spent the next few weeks watching the tournaments on grass before Wimbledon. As Stefanos Tsitsipas isn’t at his best on this surface, I discovered new players. Alexander Zverev’s serve and backhand were enough to convince me. I thought that Roger Federer could do the impossible one last time at the All-England Lawn Tennis and Criquet Club. Novak Djokovic’s game was so perfect that I couldn’t resist to it. In the blink of an eye, I was totally in love with tennis. From this summer – and all the ones after that – I spent sleepless nights watching the American swing before enjoying the US Open climax.

After all these lines, I still haven’t answered the must burning question: Why him and not another player? I often talk about his one-handed backhand and his abilities at the net to summarize. Some think that the first aspect is his biggest flaw, but I actually think that it is what defines his game – that I love so much. When it is perfectly hit, there isn’t a more beautiful gesture in tennis. Can grace take over efficiency? Stefanos Tsitsipas managed to unite both. His devastating forehand – crossed, down the lined or as a lifted volley – leaves his opponents meters away from the ball while his dazzling backhands, his dropshots and his talent at the net leave them speechless.

Stefanos, why does your first Grand Slam title still isn’t a reality? Years go by, there are more and more competitors and I sometimes think that your dream is escaping. I feel disappointed when you walk on the greatest courts of the world without really being there, when you lose in the first round of the US Open or in the Monte-Carlo quarterfinals. But when you free your talent and your will to win – against Dominic Thiem and Andy Murray at Wimbledon – I remember that you made me love tennis. There aren’t a lot of people still believing in you, but I am sure that you will win a Grand Slam one day.

Three years after the 2020 French Open, my ambitions have never been clearer. For years, I have driven myself crazy trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. Today, there isn’t any doubt. Becoming a tennis journalist is my biggest dream. Who knows, Stefanos Tsitsipas might be right in front of my in a few years to talk about the biggest achievement of his life – his first Grand Slam title.