When in 1875 Pierre Babolat founded a company producing racquet strings from sheep intestines, he could have scarcely envisioned the racquet sports dynasty he was about to build and the impact it would have on the world of tennis.

Tennis, as we know it today, took on its current shape not much earlier, and in many ways, Babolat evolved together with the sport – at times directly advancing it with technology and ingenuity.

Pierre Babolat was an expert in processing natural gut for surgical thread, musical instruments, and archery before deciding to adapt them for early tennis racquets. Through its small beginnings, Babolat became the first company to focus on racquet games. Over the years, it expanded into the production of racquet frames, clothes, footwear, stringing machines, tennis balls, grips, wrist-worn play tracking devices, and a variety of tennis accessories.

In 1925, Pierre Babolat Senior’s son, Albert, already in charge of the family business, introduced a new type of string. As the story goes, a group of French tennis players called The Musketeers – Jean Borotra, Jacques Brugnon, Henri Cochet, and René Lacoste – were sent samples of alphabetically labelled strings for testing. They settled on the one marked with a V, and thus Babolat VS was created. To date, over 100 racquets fitted with the VS string struck the winning championship shot at a Grand Slam tournament.

About the same time that Pierre Babolat sat in his Lyon apartment, not realising he was about to change the landscape of tennis forever, a group of people across La Manche was doing the same thing.

The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, as the Wimbledon club was known before it adopted its present name, is a private club founded in 1868 in Southwest London, originally for croquet only. Nine years later, in 1877, as tennis grew in popularity and croquet began to fade into the side-lined sport for enthusiasts it is now, the club decided to hold its first tennis tournament in order to pay for the repairs of the pony roller used to maintain the lawn.

Contested on grass courts by 22 players, who each paid one guinea to enter the event – about £1.05 in today’s money – and after paying out 12 guineas to the winner as the prize money, the tournament booked a profit of £10 and was able to afford the repairs. 144 years later, The Championships, as Wimbledon is known today, has grown in size and stature.

Each year, over 700 players in singles and doubles brackets enter the tournament through the main draw and qualifying round, with juniors, seniors, and exhibition matches on top of that, to compete for a slice of the £34,000,000 in prize money.

While not even the eldest tennis fans remember the first player to appear at Wimbledon with the racquet strings produced by the French company, over the next century, Babolat had a hand in some of Wimbledon’s most memorable moments.

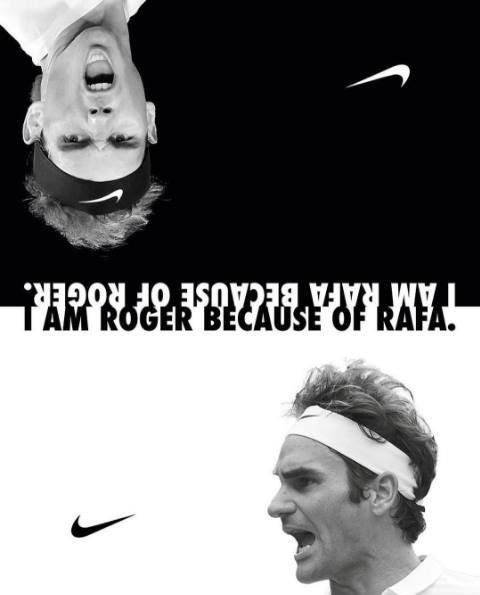

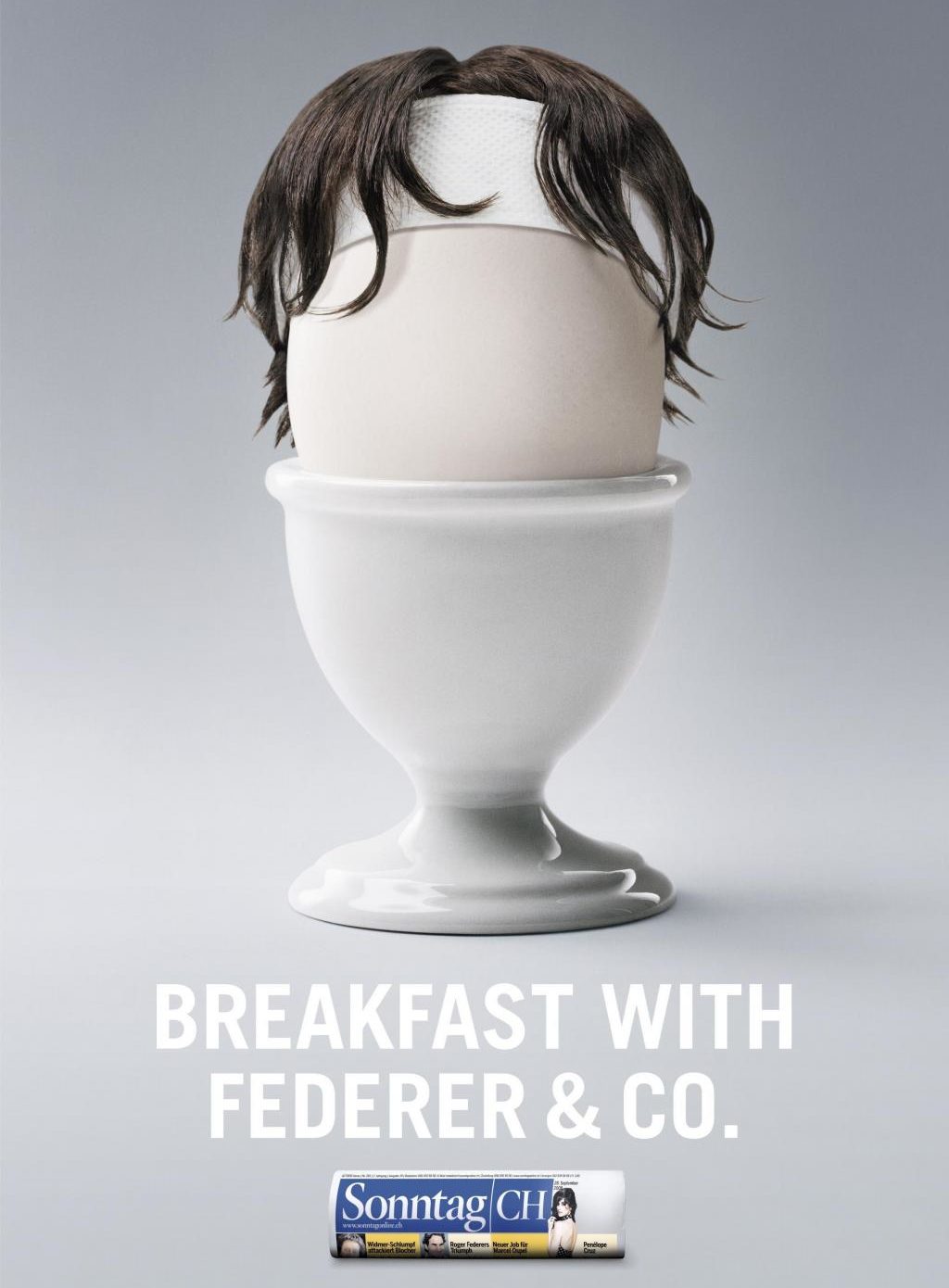

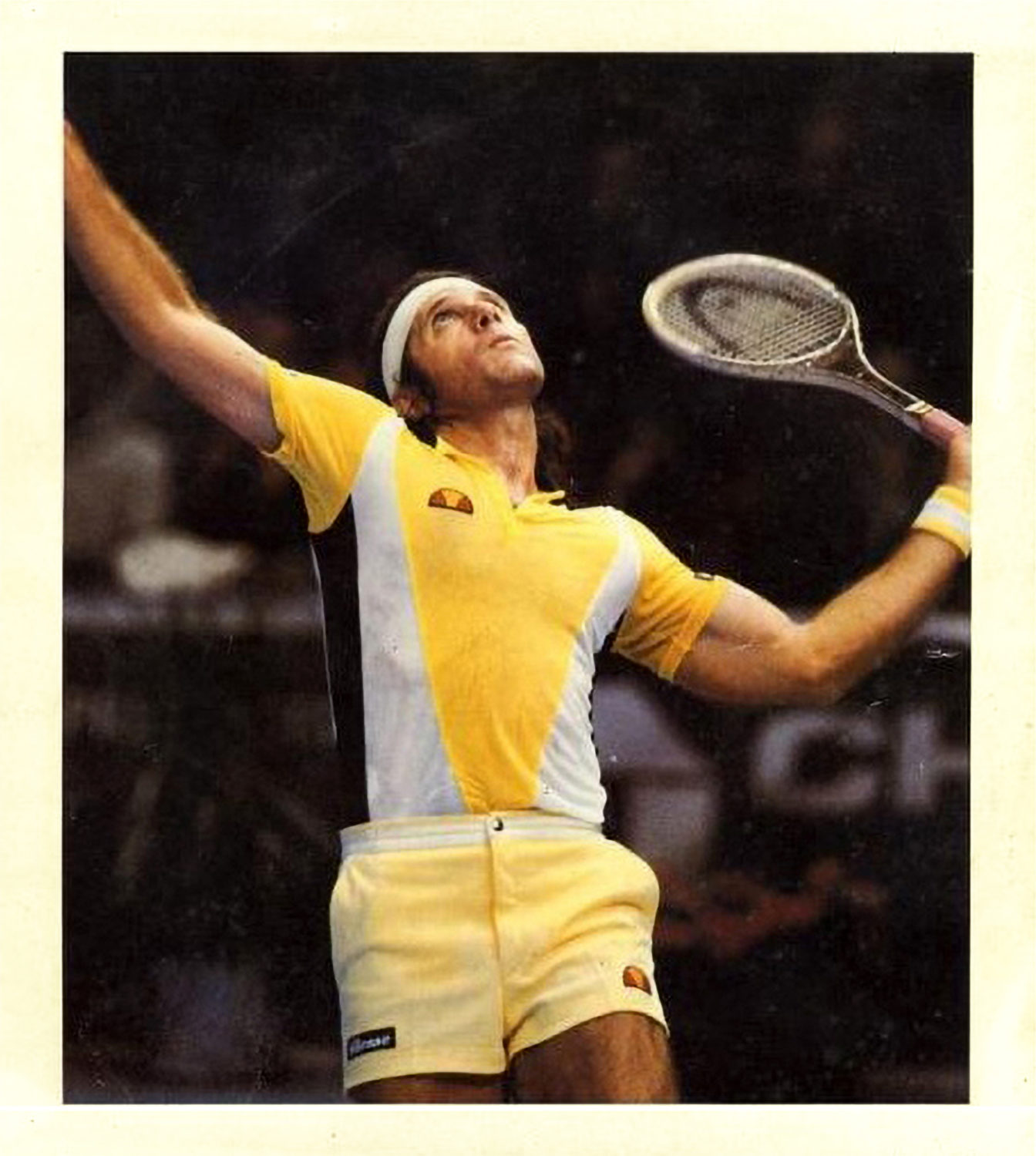

In the summer of 1976, Björn Borg became Wimbledon’s youngest male champion after blazing through the tournament without dropping a set. Borg, playing with a racquet fitted with the VS string, was the first man to do so. Three decades later, on the same hallowed turf, Rafael Nadal dropped his Babolat Pure Aero racquet to the ground in ecstasy as he snapped Roger Federer’s five-time Wimbledon-winning streak.

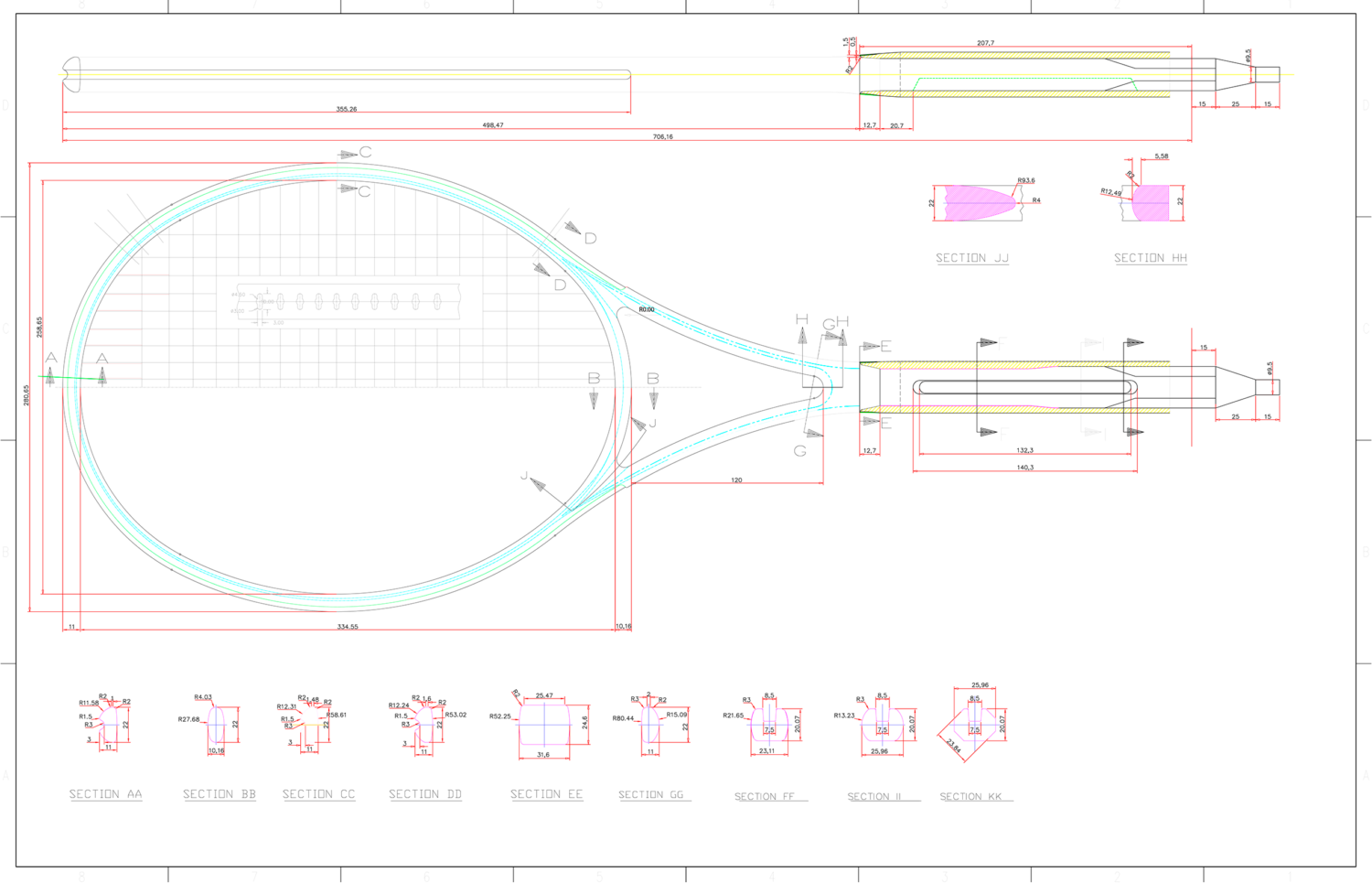

Under the leadership of Pierre Babolat and his descendants, the French company expanded its range of products from strings to tennis equipment and, in 1994, tennis racquets.

Breaking into a new market, with such established competitors as Head and Wilson, was not easy but Babolat’s lucky star – or if you are the more down-to-earth type, their scouting acumen – twinkled. At the 1998 French Open, Carlos Moyá, a 22-year-old Spaniard with the flowing hair of a matador, wielding a blue Pure Drive, became the first player using a Babolat racquet to win a Grand Slam tournament.

Two of the junior winners at the same tournament, Kim Clijsters, and Fernando González, were also using Babolat gear. Less than a year later, Moyá was ranked number one in the world while Clijsters and González were on the fast track to the tennis elite.

Today, after almost three decades, Babolat’s revenues have more than tripled and their forage into the racquet industry is widely considered a masterstroke.

In July 2017, Garbiñe Muguruza, continuing the lineage of Pure Drive-using champions started by Carlos Moyá, twirled around the centre court trying to hold back tears of happiness. After the 2015 heartbreak, when she lost in the final to Serena Williams, she was finally a Wimbledon champion.

Two months later, in September 2017, Babolat marked a special occasion – the Spanish superstars, Muguruza and Nadal, were ranked number one in the world at the same time.

It doesn’t take more than a stroll through any tennis shop to realise how far the Babolat brand has come since its inception as a string maker. From racquet frames to strings to tennis bags to clothing – today it is perfectly possible for a player to dress fully in Babolat gear, from head to toe, and compete at the highest level.

In fact, the three-time Wimbledon finalist, Andy Roddick (he lost all three finals to Mr Wimbledon himself, Roger Federer) did just that for a time. The big-serving American travelled the tour with his customised Pure Drive Roddick GT racquet, fitted with Babolat RPM Blast racquet strings, and wearing Babolat Propulse III tennis shoes. Although he never won Wimbledon, he did lift the US Open trophy, among 31 other tournaments, and reached world number one in 2003, so there is something to be said about the French brand’s ability to support champions.