The variables of everyday life make almost every human action subject to interpretation or reconsideration. Was he being friendly in the way he said hello? Was there an edge to his voice? Should I have put in a dash more salt? Will she? Did he? Should we?

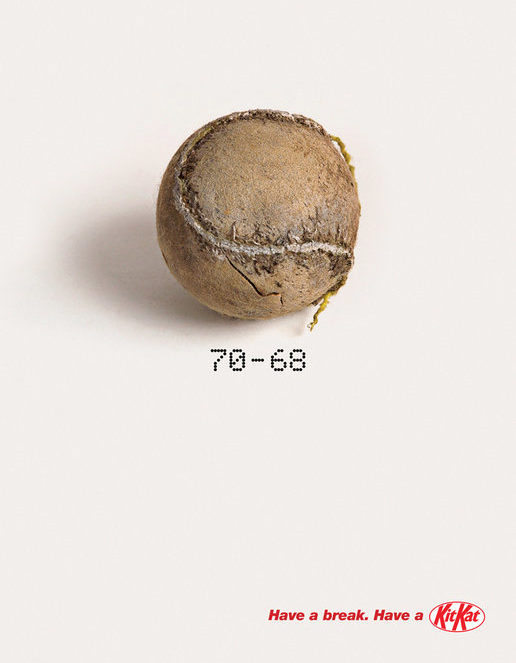

How marvelous when facts are facts. So it is with tennis. If the ball hits the line, even grazes an edge of it, the shot is in. The scoring is the same in every language—“fifteen/thirty,” “quinze/trente,” “fünfzehn/dreißig”—and even if most of us have no idea where on earth the number system came from (oh, of course there are theories, but they, too, fluctuate,) we depend on them utterly as inviolable givens. The measurements of the court are the same everywhere in the world, and so is the regulation height of the net. Total dependability is so rare in life; thank goodness for the regulating system of the game that for many of us is a source of constancy and balance in life.

But the nuances of tennis are something else. The time taken between when Nadal is expected to serve and when he actually does so can drive not only his opponents, but the umpires, nuts. (Yes, now there is a regulation.) How loud does a grunt have to be before it rates as a downright interference to the play of the person on the other side of the net? When is a bird landing on the court reason for calling a “let?” And then there are the subtleties of tennis etiquette and mannerisms. Here we enter another world.

As a teenager, I occasionally played with a lovely debutante who interested me in ways that made the idea of suggesting tennis to her simply a device to get to know her better off the court. But, first, the term “debutante” requires explanation in a publication that is largely francophone, and this young woman’s classification as such has to do with her tennis manners. In the sense I have used it here, “debutante” by no means “beginner,” as it does in French. It refers very specifically to young ladies of significant financial means who are “presented to society” at formal events where they dance first with their fathers—or stand-ins for their fathers if, for example, Declan, Bobo’s first husband and therefore Poohpooh’s real father, fled to the Bahamas when Poohpooh was little, and now Bobo is married to nice responsible Roger, a stalwart stepfather much better suited to “presenting” Poohpooh—and then get whirled around the dance floor by a sequence of suitable young men. These events at which debutantes become part of grown-up society are called “coming out parties,” a term that precedes by about a century the use of “coming out” as a reference to people revealing their previously hidden sexuality. Debutantes were expected to behave both correctly and incorrectly—one hoped there was a tendency toward misbehavior just waiting to be ignited underneath their impeccable social customs—and were the stuff of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short stories.

The debutante with whom I played tennis is hard to imagine in anything other than a perfect little black dress and string of pearls, but on the tennis court she was in flawless white. And she had a habit that made a powerful impression on me. If, on my first serve, I served a “let”—which is to say that the ball ended up in the correct service box but had audibly grazed the top of the net en route—she would say “Take two, please.” She said it sweetly, graciously, as if she were offering me a canape on a silver platter. And if the “let” occurred on my second serve, she would say “Take one, please.” It was invariable. I have never known of anyone else to say “please” with the routine “Take another,” but this young woman invariably did so, and it was clearly so ingrained in her that it would have been impossible for her not to use this extraordinary form of politeness.

Forty years later, I was seated next to the debutante’s mother—Alexander Calder did a wire sculpture to which he gave that name, and it is sheer perfection of a particular American social type—at dinner at one of those American country clubs where the red clay tennis courts are rolled to perfection and the food as tasteless and bland and predictable as the clay before players’ footprints have put a bit of variety into it. By the time of this dinner alongside her mother, the debutante had led a life that was less than her mother had hoped for, the influence of gin a major factor. Her mother, a force, was truly a “doer” in the world, and openly disapproving of her daughter as the young heiress who had not realized her potential.

I decided, in defense of my tennis-inamorata of forty years previously, to tell “Mummy”—this is what debutantes called their mothers, no matter what their ages are—how I still play a lot of tennis and, every single time someone hits a let, I remember that “please” with which her daughter always followed “Take two” or “Take one.” To this day, I take pleasure in the memory of this particular niceness.

The mother loved the story. It was as if she, as a parent, had done something right—to have brought up a child with such a lovely and unusual habit.

But what one says and does on the tennis court does not always land as intended. I have no idea when in my life I got into tennis games that began where the first time that each player served, whether or not he or she had done some practice serves, one began with “first one in.” This means that one could hit any number of faults, but, starting with the first attempted serve after you have agreed to begin, the game only actually begins with the first serve that is good. Each player—whether it is singles or doubles—has this chance to play with “first one in.”

I recently started to play tennis regularly with my son-in-law, one of my favorite people on the earth. This was one of the fortuitous by-products of the lockdown caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and reflects circumstances so rare and lucky that I am embarrassed to admit them. I live in Ireland and have a tennis court that is located between my wife’s and my house and a second house where our children and grandchildren stay. So in a time period when few people had access to tennis, Robbie—married to my daughter Charlotte—and I could play. We wore surgical gloves because of concerns about germs being passed on the surfaces of tennis balls, and were never closer to one another than two meters, except possibly when, at the end of our matches, with our arms fully extended, we clapped our rackets in lieu of shaking hands.

Robbie is affable and energetic, and has a brilliant sense of humor, and tennis became our chance to be together in a wonderful way. We don’t chat when playing—we put all family concerns to the side—and our only conversation is one of us complimenting the other on a shot; each of us is genuinely happy for the other on the occasion of an ace or a well-placed powerful groundstroke.

For whatever reason, we developed, from the start, the habit of his being the first to serve. The third or fourth time that we were playing, he asked me, in no uncertain terms, not to offer “first one in.” He is someone who is rarely annoyed, but when he is, you know it, and I could see that the offering bothered him.

Afterwards, I asked him about it, he said that he considered “first one in” patronizing. I explained to him that it was an old habit of mine—that it had nothing to do with my wanting to give him a chance I would not also have—and was normally reciprocal. I realize in retrospect that in fact he never did say “first one in” to me when I followed him for the first time as server, but I had not noticed that. I assured him that it was not an insult to his serving capability, or an attempt to give him some advantage I did not have, and that it was a very old habit for me.

I wrote a number of friends who play tennis to ask their views on “first one in.” I prefaced the letter by saying I realized that it was a time period when few of us could be on the court, given the lockdowns of the pandemic, but lots of us had more time than usual to read and answer email. The answers were all over the map. A woman in her eighties who has played for most of her life said that “first one in” was de rigueur in her regular Tuesday morning women’s doubles game, but of course absolutely out of question in tournaments. It became clear to me that no one outside of America had even heard of the habit. Not only do my son-in-law and I play in Ireland, but he is Irish, proficient at rugby and soccer and countless other sports, and “first one in” has no equivalent, or history, in any of the sports he plays, and must have seemed like the disgraceful notion of a “Mulligan” in golf.

The replies to my inquiries about “first one in” were rich. One was from Willem van Roij, a great friend who lives in the Netherlands. He wrote,

It is interesting that you start your email with the assumption that few people are spending a lot of time on the tennis court. You should know that I have been thinking about it last week, because in the Netherlands all sports clubs, gyms, health centers etc. are closed because of Covid-19. And it makes perfect sense that you shouldn’t go to the gym with other people, or play team sports where you have to be close to one another or even have physical contact. But why are all public tennis courts closed? I would say that you can easily play tennis and keep your 1.5m distance from each other.

Anyway, “first one in.” The first time I heard of this etiquette was when I played tennis on the most wonderful and amazing tennis court I have ever played on. It was a summer one shall not easily forget, temperature records were broken, and I actually noticed my boss—who usually dresses neat and formal—driving around bare chested in his red Fiat 500. It was June 2018, West-Cork.

I have played tennis since I was young, probably age five or six. It all started on the second most wonderful court, the one in the garden of my family’s summer house in rural Belgian Ardennes. This one didn’t have the same view as the one in Glandore, but still, it was amazing, surrounded by woods and, depending on the season and whether trees had just been cut down, we did have a view on the adjacent village and its church tower on the other side of the valley. When Clim and I got married, I didn’t want a present from my grandmother (who was luckily still alive by then,) but I begged her for a painting that was in the summer house and that represented the church of the adjacent village. The painting is not great, it is by a minor local artist, but every time I look at it, I am back in the summer house garden, playing tennis with my father.

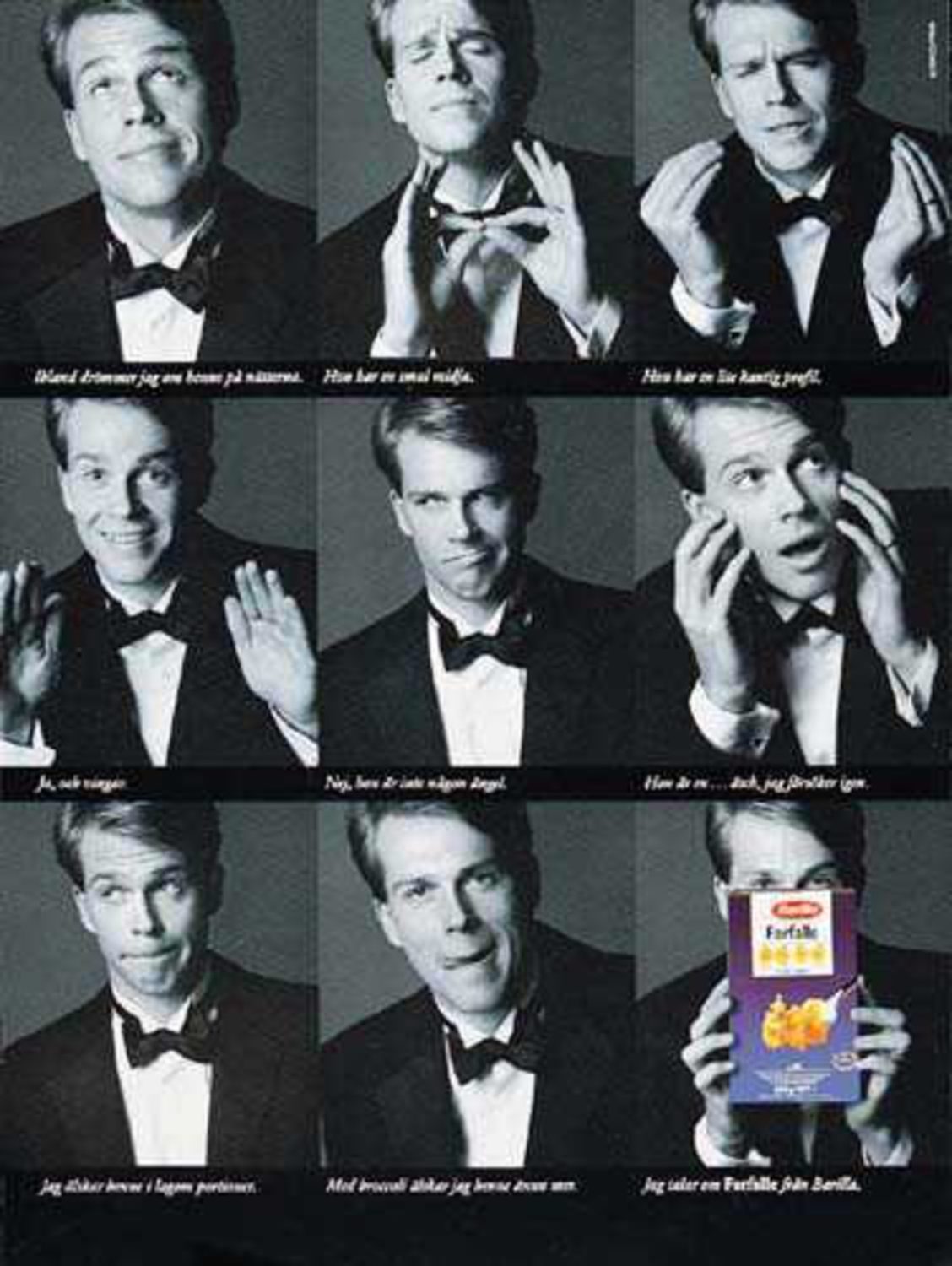

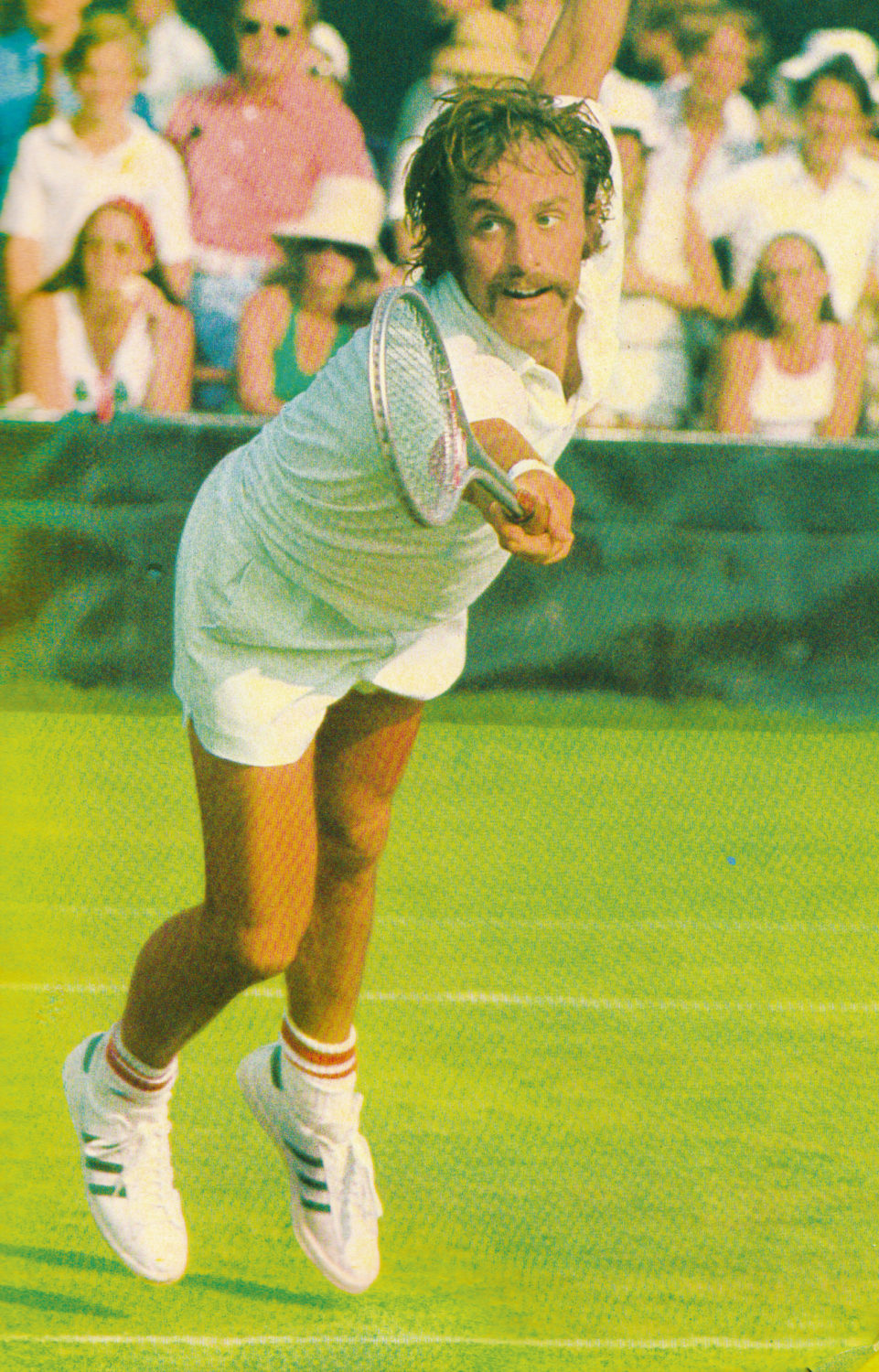

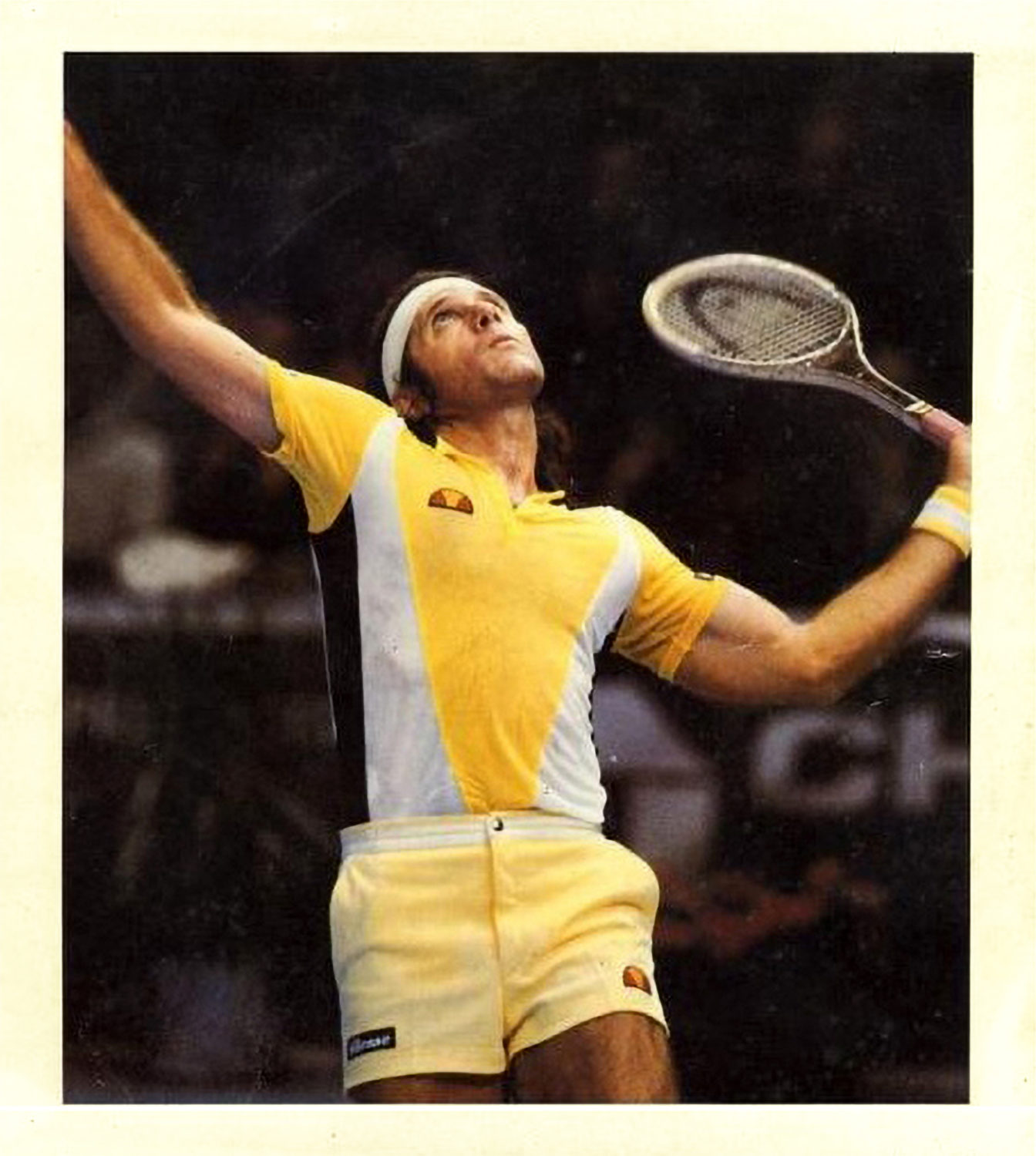

So playing tennis started with my father, first on our own court, later also on the public courts of the village we lived in. Sunday morning, 9:00 am sharp, I can picture my father in a white Adidas polo shirt, with a Miro-like sign of Stefan Edberg on it (it was the late 1980s,) my God, I envied him for that shirt. Of course, we started warming up, followed by some baseline rallies and then practicing serves. Then the game began, and I just cannot remember something like “first one in.” Neither when I later started playing tennis with kids of my own age. It was always after practicing serves that we simply started with the usual two serves.

And so when in 2018 you proposed “first one in,” I thought it was a gentleman’s proposal by an experienced player to a man who clearly—and visibly—had not played tennis for years, and from whom you obviously could win. And thinking about it, there is nothing wrong with a nice gesture in a friendly game, if both agree on this beforehand. To take the usual two serves, miss them both and then request for a “first one in” is poor form. In that case, the pardoning power lies with the playing partner, who might offer a re-do. But there is also something to say for not offering “first one in,” since it is some kind of practice, and when you start the game and the first serve, you are playing, not practicing: every serve counts.

Since I am the person he refers to as his “boss,” and the tennis court is the one on which I play with Robbie, the letter had particular charm. It took the circumstances of the lockdown to evoke these superb memories from Willem; a minor question had resulted in glorious writing.

It may have been a symptom of the lockdown that so many people answered me in depth. Another great reply came from Ray Nolan, a local friend in Ireland who made his reputation as a rugby player and is now a tech entrepreneur. He trounces me when we play tennis, but we have great games—at least from my point of view. He answered,

Hey Nick,

It’s great to hear from you—and I trust, given you’re at least thinking about tennis, that all is well in your world.

I’d never heard of the concept of “first one in” until you graciously invited me to play in Glandore. I liked it a lot.

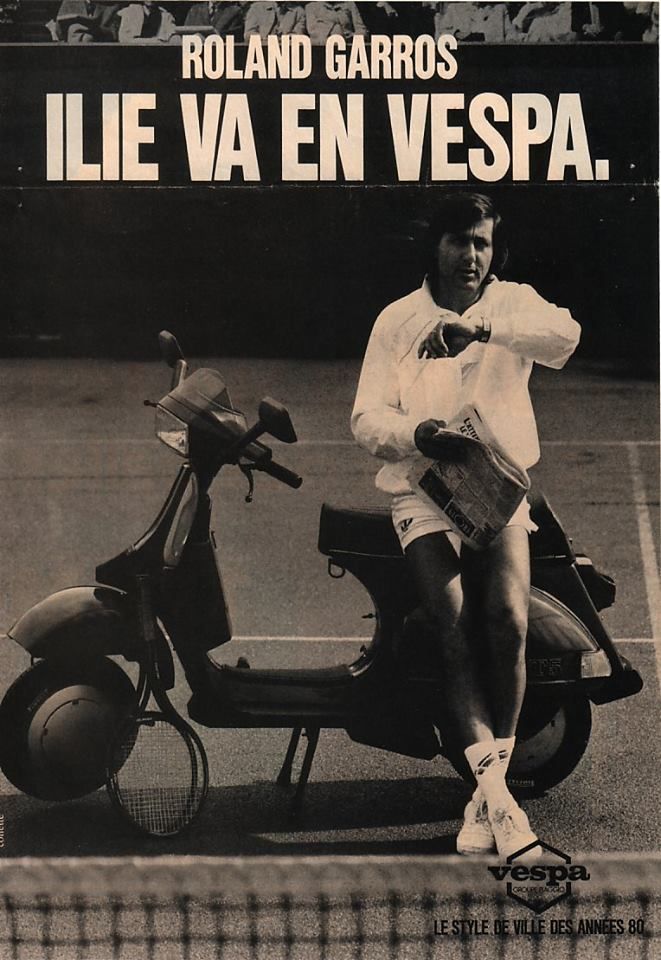

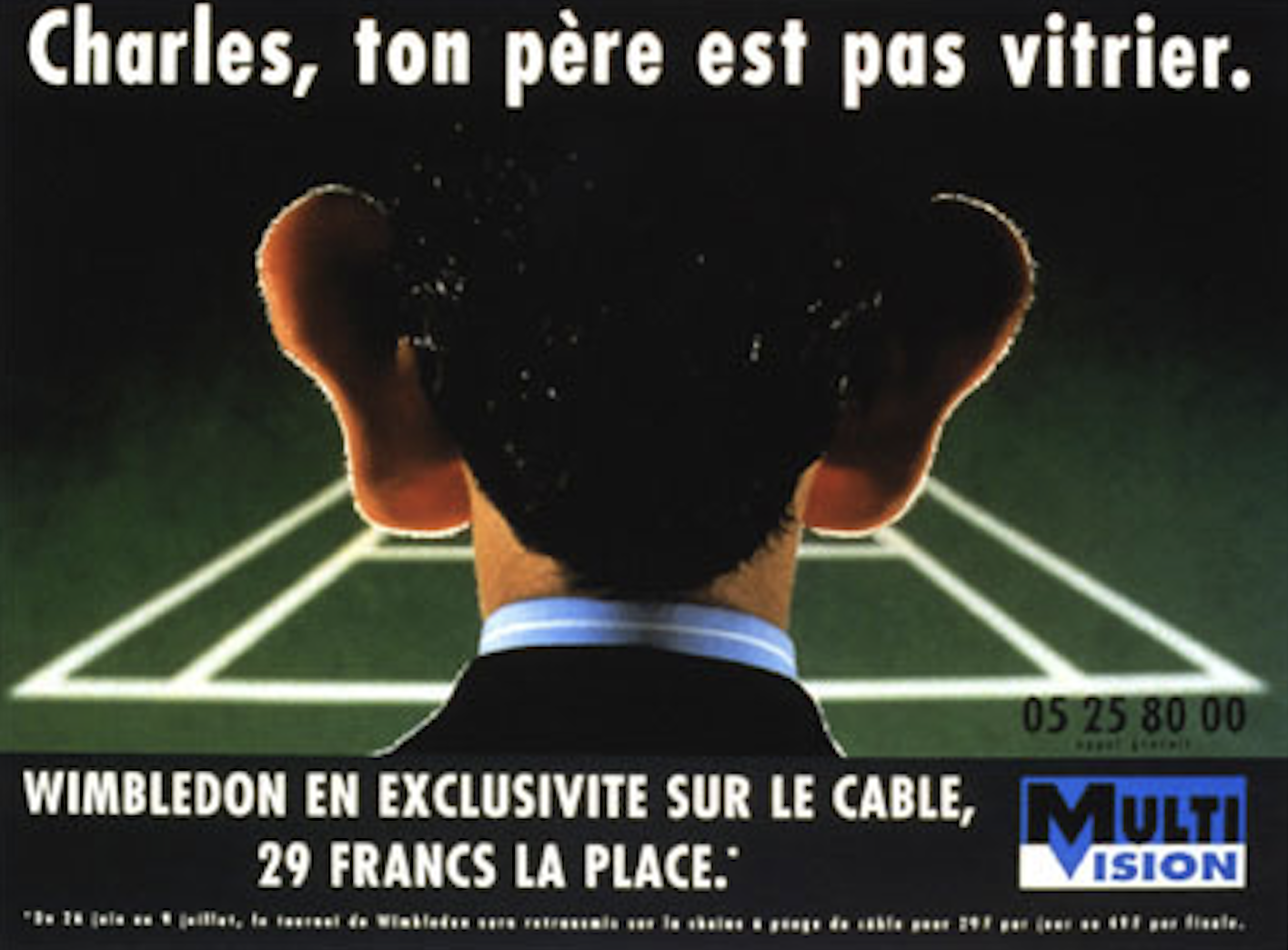

It saves time. Many of us do not have the luxury of boundless time on our own courts, but instead need to return to the drudgery of our normal lives—also known as “time not on the court.” And so, the need for multiple practice serves taken away, we get more time competing and less time faffing around. In doubles it’s of course much worse. I’ve played numerous league matches lately where players routinely take perhaps eight serves from each side in the warm up. We are none of us playing in Roland Garros, or at a standard anywhere near that, so this is surely overkill.

It’s also a signal of friendly rivalry. Calling “first one in” acknowledges, that whilst we will definitely compete, this match will be about smiles not grimaces. It’s “welcome to our game” versus “ready set go!”.

For league matches, or trophy games, I believe a modest two practice serves to each of ad and deuce courts, followed by formal start is appropriate. But “first one in”… that’s perfect for a summer’s day overlooking the bay, hitting more losers than winners, but enjoying it for all of that.

There is a far worse crime in tennis however—one that requires a greater penalty than just modest disdain, and I will ask this of you soon. I’ll let this crime settle first.

Naturally I egged Ray on. What was he referring to? Ray is a sportsman par excellence, a big thinker, a robust character with a keen sense of fun and a kindness that he exudes from every pore.

His essay on “the crime,” the sign-off of this narrative, is another of the many questions that leaves us tennis aficionados something to ponder:

“Foot Fault”—I yell it from the far end of the court. I double-check—did I say it out loud? I know what’s coming.

“Whad’ya mean?” My opponent beckons, clearly irritated.

And so its begins, another tennis match where one protagonist will be righteous, and one will be irritated by what he sees as pedantry by his opponent.

It’s a class 4 club game—nothing important. There are no umpires, that’s for sure. And if there were one, an umpire at this level would never call a foot fault, even if it were the final of the club champs.

Foot-faulting, the process whereby the servers’ foot touches or crosses the baseline before he or she connects with the ball, is against the rules of tennis. To me, it is no less important as calling a ball in or out. And as with line-calls, there is no grey area.

Bad line callers—we all know folks in our own clubs—are muttered about—“There’s Pete”, as he passes out of earshot, “an horrendous line caller—let me tell you about the near-fisticuffs we got into in an away match at Fitzwilliam.” There is no ambiguity here—a bad line caller is a cheat, end of! And a cheat in sport is someone not to be trusted.

And yet some sixty percent of club players I observe routinely foot fault. Those same whisperers who call out Pete then foot fault every single time they serve the ball. They are not unaware of the issue—they do it knowingly. They cheat!

Foot faulting is no less serious than making a deliberately erroneous line-call, grounding your golf club in the bunker, or delivering a sly rabbit punch at the bottom of a ruck.

Like all cheats in sport, they do so to gain an advantage. If I can get to the net quicker by starting six inches nearer that means I make a volley that I might not have made. If I serve forward of the line, I’m creating the same vertical angle of attack that someone 6’ 4” would achieve. If I serve wide from here, I’m achieving a lateral angle that would not be possible if I’d been behind the line. If I can cause my opponent to be irritated and concentrate on the position of my feet rather than the ball I’m about to hit…

In getting to fifty-something, I’ve played a few sports over the years. Rugby, where I’d eat a sly rabbit punch at the bottom of a ruck; golf, where self-regulation is the order of the day, yet we all know about “Donald who often forgets the third shot out of the bunker.” But tennis, largely played in my neck of the woods by middle aged folks in pure white—Nobody cheats at tennis?!

Yet, in no other sport is a rule so flagrantly ignored than foot-faulting in tennis.

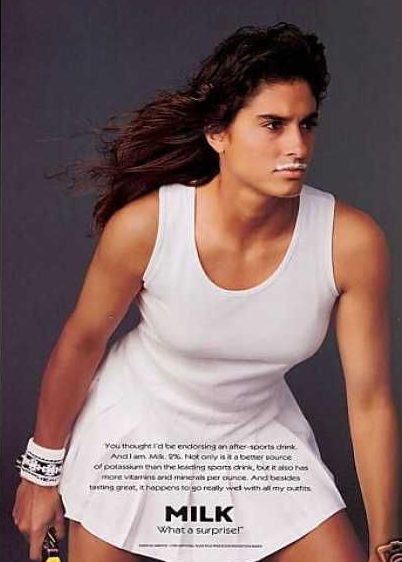

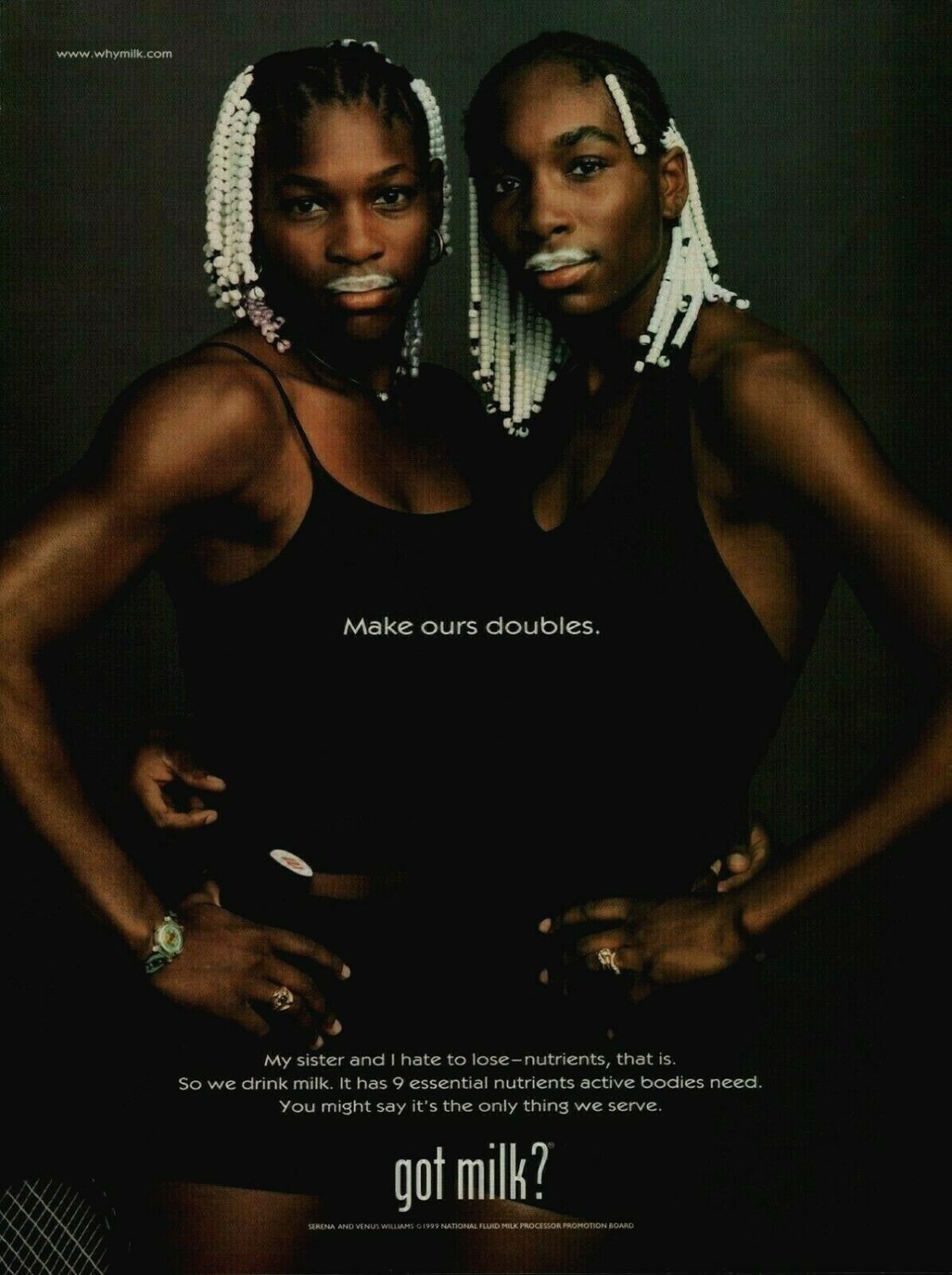

It goes right to the top too. Serena Williams, a multiple grand slam winner, and possibly the greatest female player of all time, routinely foot faults. I know. I’ve had the good fortune to get a seat at Wimbledon right on the baseline. Only a brave line judge would call her on it. One did a few years ago and was hit with a level of threatening verbal abuse that no individual should ever have to endure.

Once, in trying to rebalance a game where my opponent routinely found himself two or three feet nearer the net, I challenged. “I can’t call you for foot faults—right?” “No” “Okay then.” When next it came time for me to serve, I set up behind the baseline, then took a meter-long step inside the court before tossing the ball to serve. “You can’t do that!” came the indignant roar. You can guess the rest I’m sure.

Alternatively, I’ve considered making a deliberately bad line call, then admitting to it, but stating that “if the line does not apply to your feet, then it surely cannot apply to the ball.”

Don’t get me wrong. People occasionally foot fault in error. That’s sport. Contenders striving to get the max advantage within the rules is the very essence of sport. As with the offside line in rugby or soccer—getting close to the margins is to be praised. But those who’ve built a foot-fault into their service action are no less culpable than the All Blacks, who routinely sneak a yard or two behind the ref’s back, or the soccer striker who plainly dives for a penalty.

The golf world was apoplectic recently when Patrick Reed was seen on TV to have grounded his club in the bunker during an important competition. Some said he was “building sandcastles.”

So fellow tennis players—a question—“Are you building sand castles?”

Article publié dans COURTS n° 8, été 2020.