I

Got

Into

Tennis

Photography

by Pure Chance

An interview with Ray Giubilo

As I make my way through the leafy suburbs of Wimbledon, approaching the meeting point at the Tennis Gallery, I spot Ray crouched in front of the entrance. He’s taking a photo of a small dog. Phone in hand, he’s twisting around to find the perfect angle. “He’s peering inside the shop. Look at how curious he is,” Ray says pointing at the dog as he notices me. “I think this is going to be a nice photo.”

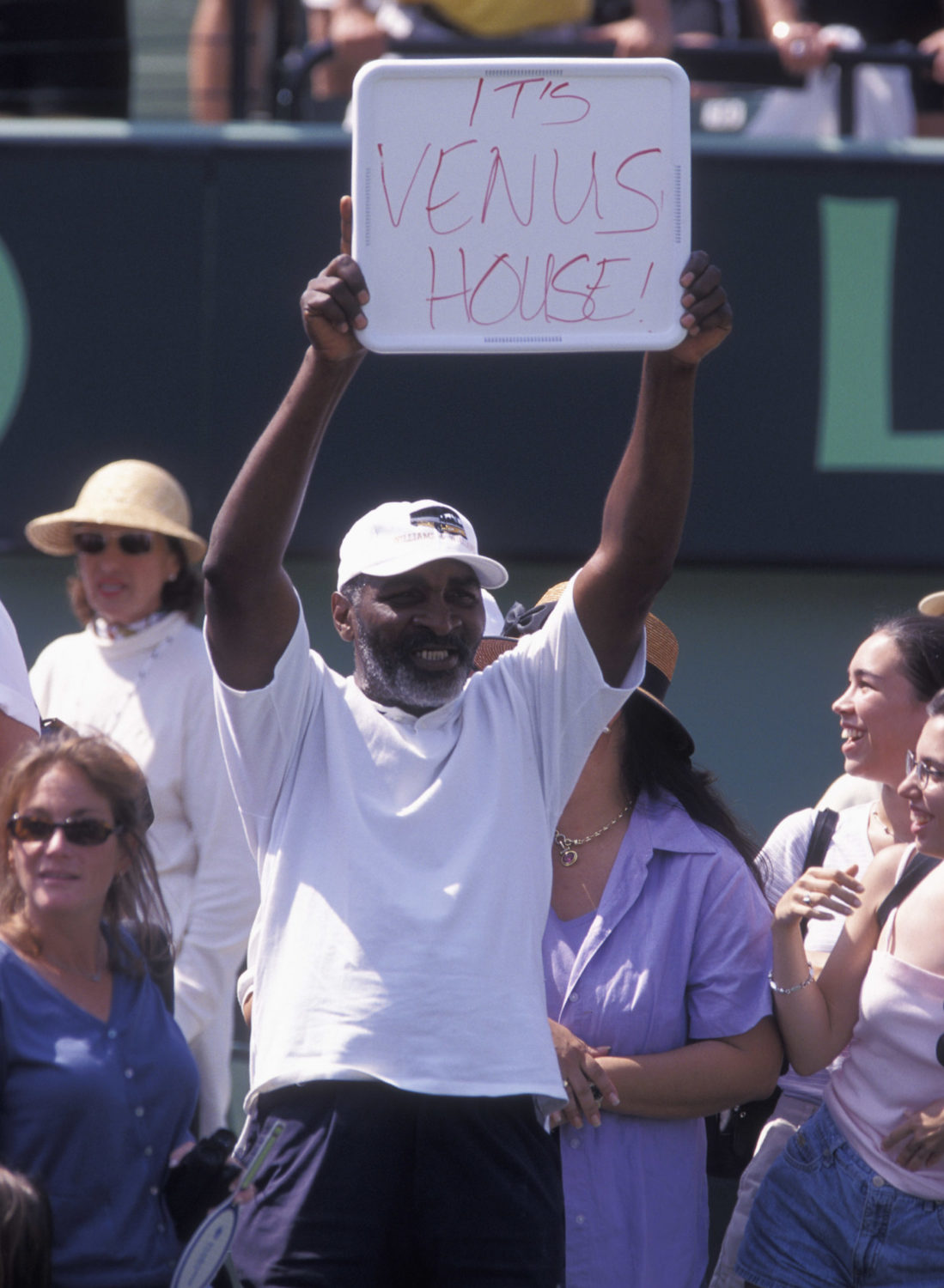

When Ray Giubilo stands up, he unfolds his 6 ft, broad-shouldered frame, and as his amiable, Buddha-like face draws level with mine, it breaks open into a warm smile. We bump elbows and start down the road towards one of the many coffee shops that populate this quiet area of Wimbledon. It’s the middle Sunday of the Championships, a break day, his last one as far as Ray is concerned. Next year, the tournament plans to move away from its long-standing tradition of a day off, and Ray has agreed to spend this afternoon talking to me about his life on the tennis tour as a professional photographer. He’s dressed in casual tones, wearing thin-rimmed glasses, a faded-navy safari jacket, and blue jeans. The sky, ominous and cloudy, and threatening rain all morning, suddenly opens up and lashes us with a warm, summery drizzle. Ray opens his umbrella and invites me under. I ask about the dog photo and Ray offers me an impromptu lesson in photography. “You know,” he says in a raspy yet friendly voice, “To take a perfect photo you need the perfect light, the perfect exposure, and the perfect subject. But the perfect photo could also happen unexpectedly.” He takes out his phone and starts scrolling through the vast library of photos, finally stopping at one of a butterfly hovering around Rafa Nadal mid-play. “This is a great one I took. He was about to serve and got hypnotised by the butterfly.” Ray’s tone switches from that of a professor lecturing students to a veteran recounting his adventures. “I took a great photo of Venus Williams once. It was on film, so I wasn’t sure at the time. I was with two friends and I said to them, ‘I think I’ve got a great picture. I think.’ I didn’t know until the next day. I was lucky.”

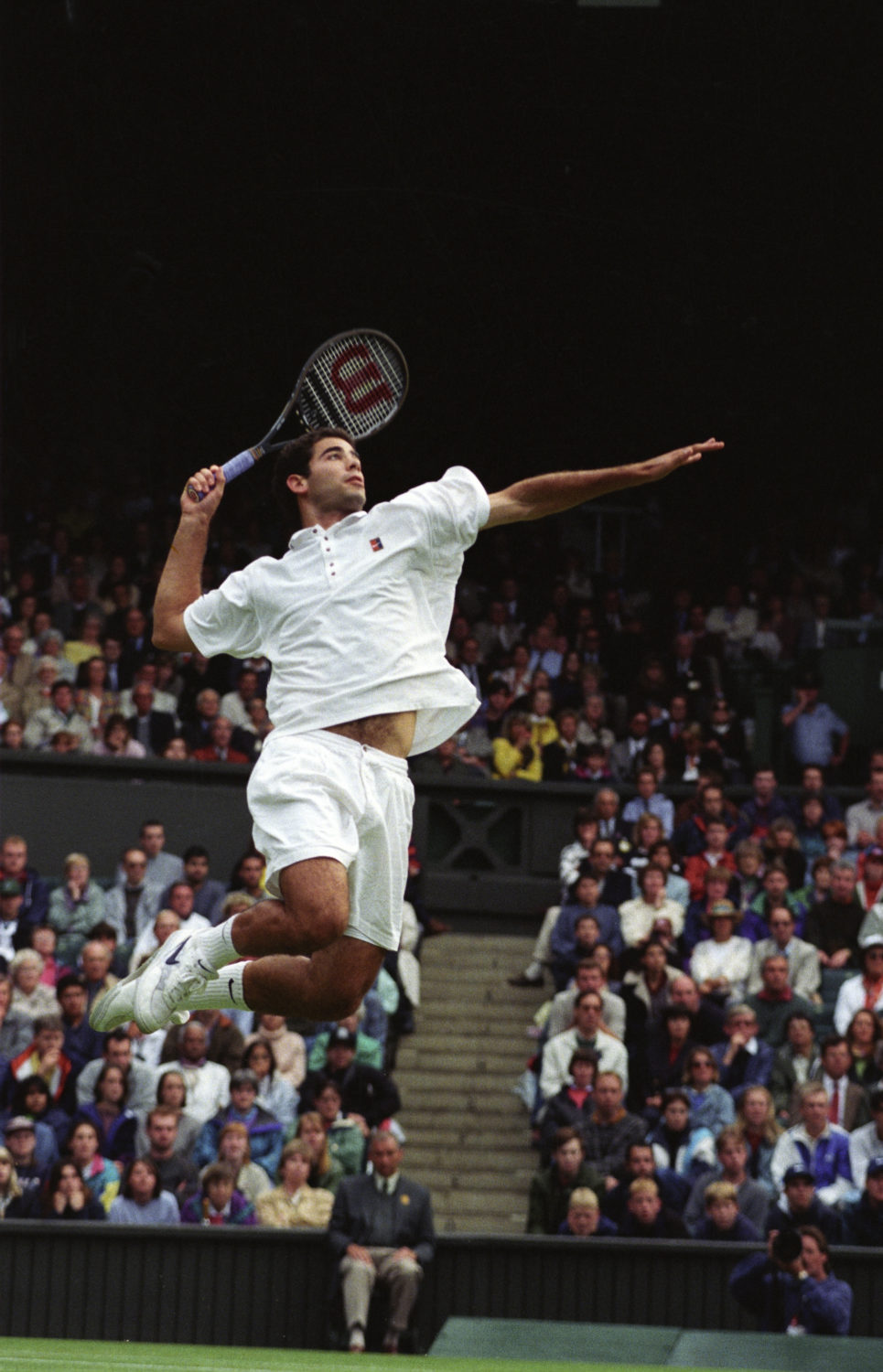

“There is one that I particularly love, one of the first good photos I took. It was Sampras at Wimbledon centre court in 1996, and it became this famous photo because Wilson used it for advertising. It became iconic,” he pauses for a moment, then a big smile lights up his face. “But my favourite is the Venus Williams one.” We take a table away from the noise and Ray orders an espresso macchiato. When it arrives, he inspects the cup with the eye of a connoisseur. “When I travel for work, I always bring my own coffee maker. You know, the old type where you put the water, the coffee, and the filter. I bring my own tin of coffee, too,” he says, taking a sip. Ray Giubilo is a born raconteur. Being a photographer, it is safe to assume that he subscribes to the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words. And it probably is, but he won’t risk it. “I always take my coffee with me. That and my music,” he continues. “I listen to a lot of music – blues, jazz, jazz fusion, progressive – mostly from the 60s and 70s. Over the years, I saw a lot of concerts. I still do. I saw Roger Waters in Paris, during the Us+Them tour, which was very good and very political. Very strong against the Trump administration. And then in Hyde Park, I saw, on the same day, Steve Winwood, Carlos Santana, Eric Clapton, and Gary Clark Jr.,” he says with pride.

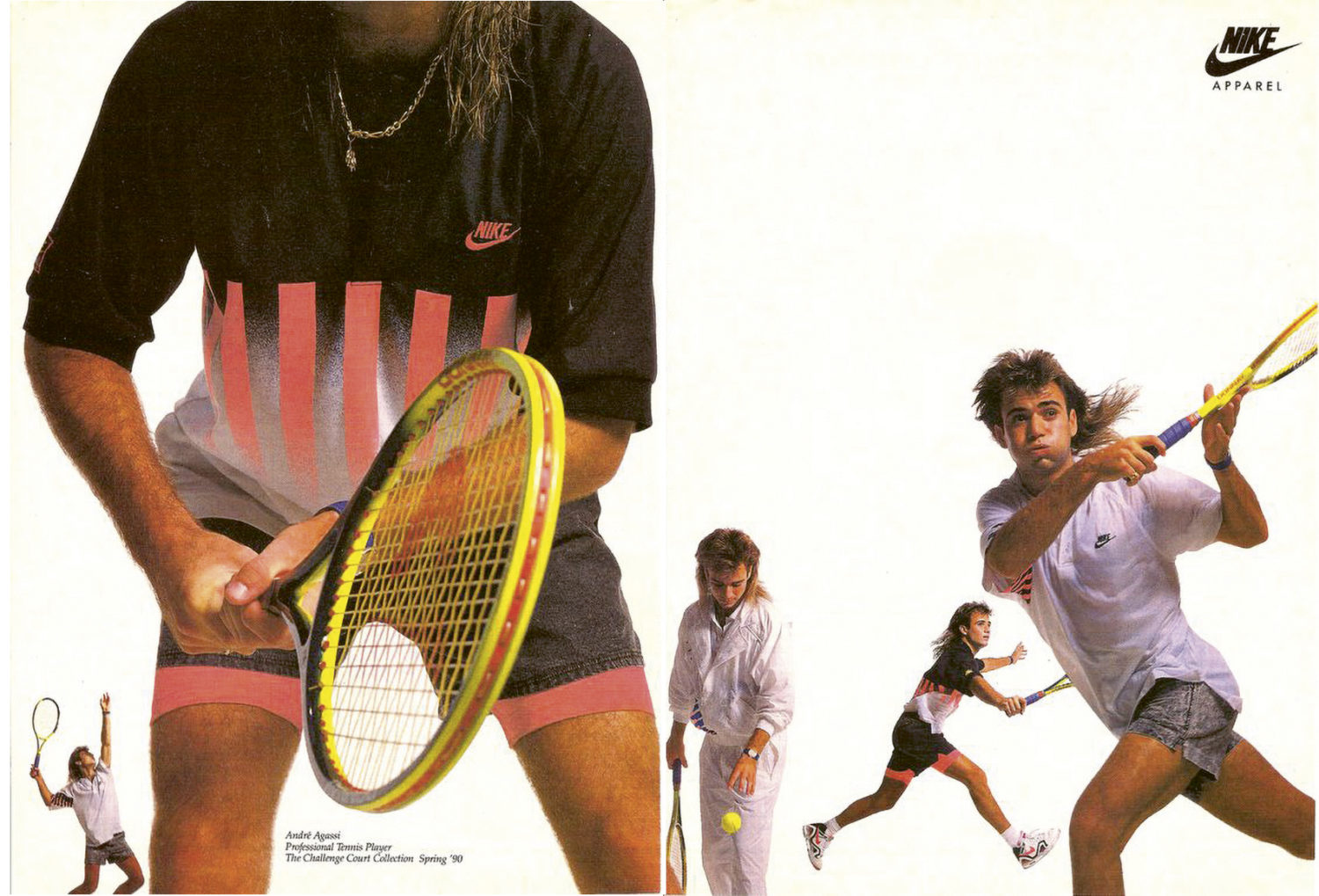

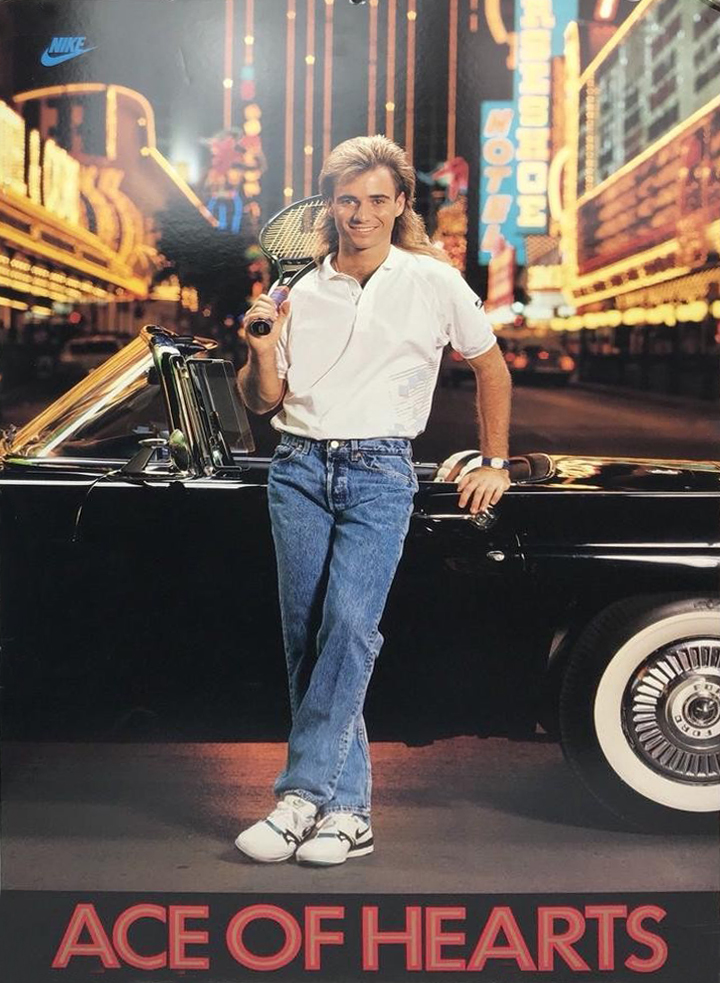

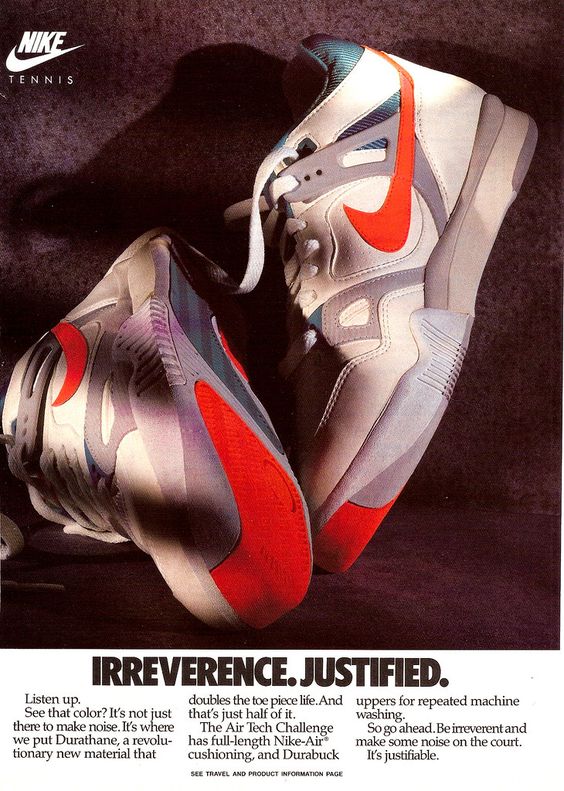

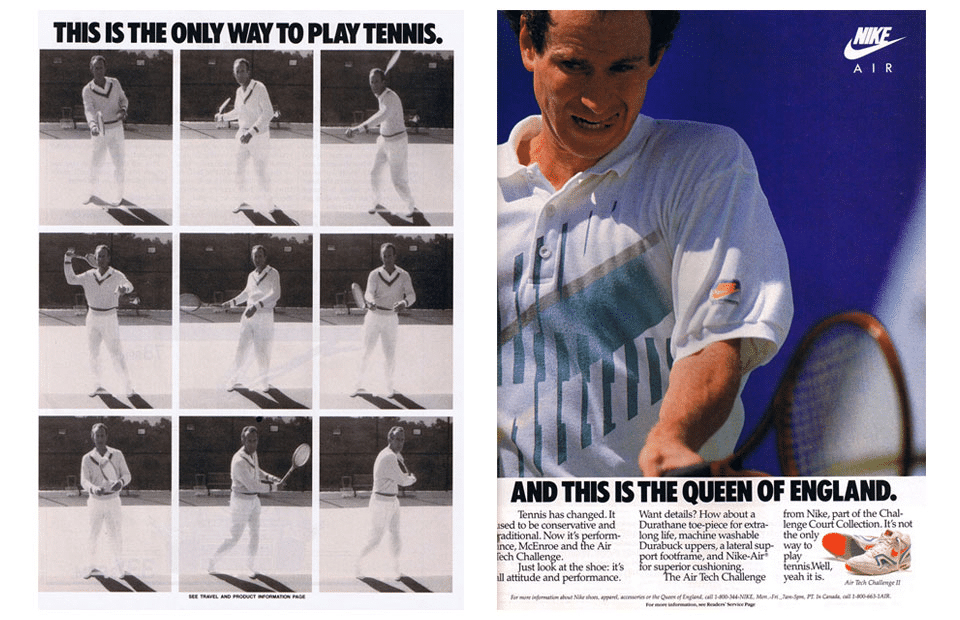

Ray Giubilo’s work as a tennis photographer means he is always on the move. The pages in his passport are crammed with stamps: over 100 Grand Slam tournaments, a myriad ATP and WTA events, Davis Cup and Fed Cup ties, four Olympics – in total over 300 events, 14 to 16 tennis tournaments a year. His first camera was a gift for First Communion. “It was this tiny thing and I couldn’t believe that it could take photographs,” he recalls with a smile. “That was my first experience with photography. Later, when I was studying, I took photography as one of the elective subjects, and that’s how I started.” Ray takes another sip of coffee and settles into a slow, measured tone of a storyteller. “I got into tennis photography by pure chance. I used to do fashion photography, and it was really tough because in Australia, in the mid-80s, there was a boom in fashion photography. A lot of locals started getting into fashion, and other photographers, young ones, started coming from New York and Paris,” he recounts. “They were much more experienced and had a list of contacts in magazines that they were using for work,” Ray continues. “So, it was very hard to get into that kind of photography because there were very few magazines and lots of photographers. But I still learned a lot.” To say that Ray’s eyes grow vacant as he navigates the foggy past of his memory would make for a decent line but it would also be a lie. When he tells his story, Ray is alert and lively. His teeth often flash in a grin and he accentuates his narrative with frequent bursts of laughter.

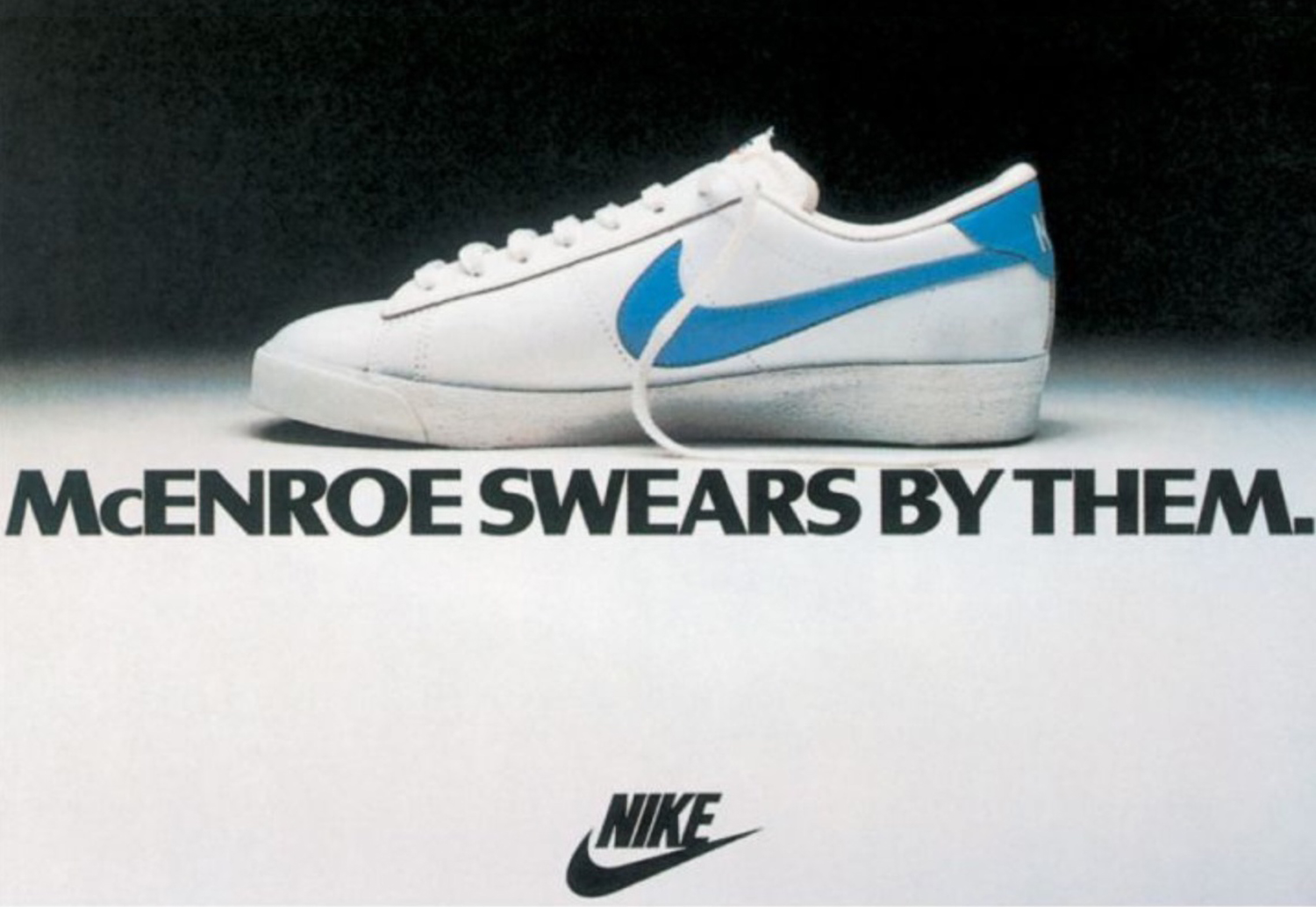

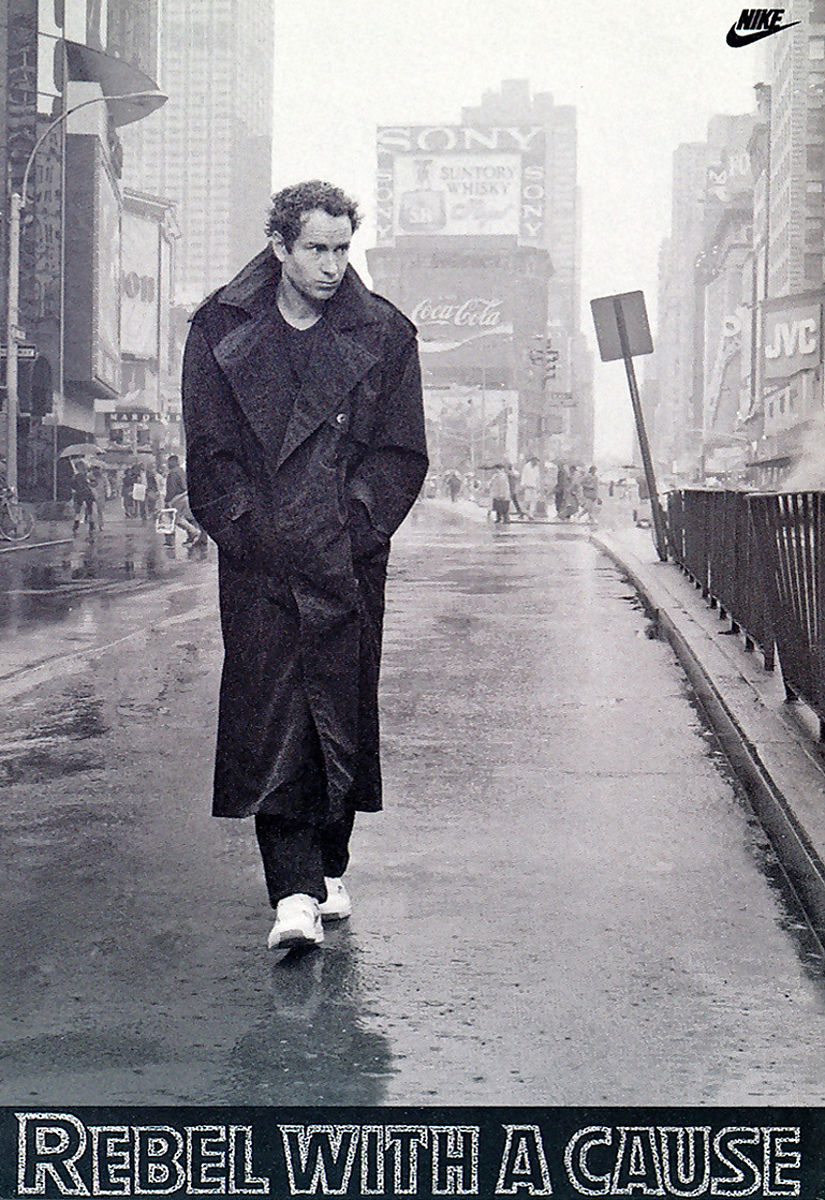

“My family moved to Italy when I was 7 years old but I was born in Australia. When we moved, I suddenly found myself in a country with a completely different culture and a different way of thinking,” he continues. “When I was 20 years old, I travelled to England to study. I wanted to learn the language. I studied marketing for two years in Essex before moving back to Italy and finishing it there. After that, I decided to go to Australia. But before I did, in 1981, I went to visit a good friend of mine who worked for Sergio Tacchini. I was planning to stay with him for a few days. One evening, when I was visiting him at the office, Sergio Tacchini gave us a lift,” Ray says. “So, I’m in his car, and he makes small talk. ‘What do you do?’ he asks me, and I go, ‘Well, I’m moving to Australia soon, but I don’t know what I’m going to do. I don’t have a job there, but I’ll find something,’” he remembers. “Then, he asks me, ‘What have you studied?’ and I tell him, ‘Marketing,’ and so he says, ‘How about if I give you two suitcases of sports clothes, and you try to see if you can start a market for me there.’ We organised all that, and I went to Australia. When I arrived in Sydney, I went for a walk through the city centre, and had a look at all the sports stores and department stores to see if they were selling any tennis clothes. There was a little bit of local stock, but nothing international. I looked up who was distributing what, scheduled some calls, and after about a month, I found somebody willing to be the importer. In the end, we managed to get 100 shops selling Sergio Tacchini clothes in Australia,” Ray says.

“As I was selling clothes, another friend of mine started the Sergio Tacchini magazine. He was a lawyer and a journalist, and he started putting the magazine together three to four times a year. He was also writing for Matchball which, at the time, was the best tennis magazine in Italy. In 1989, my friend said to me, ‘I’m coming to the Australian Open for the Matchball magazine. Do you want to come with me?’ And I thought, ‘Okay, but how do I get in?’ I was already working as a fashion photographer and working for Sergio Tacchini at the same time. ‘I’ll get you an accreditation,’ he said. We drove to Melbourne from Sydney, and it was a long trip. We blew the head gasket halfway and had to put the car in the garage, but we managed to get to Melbourne. We got to the tournament, and I started shooting photos for the magazine, but I had no idea what the rules are and what I’m supposed to do. So, I would observe the other photographers and what they were doing. In the end, I managed to get more than 100 photos published. And I thought, ‘Wow, this is great. This is what I want to be doing.’”

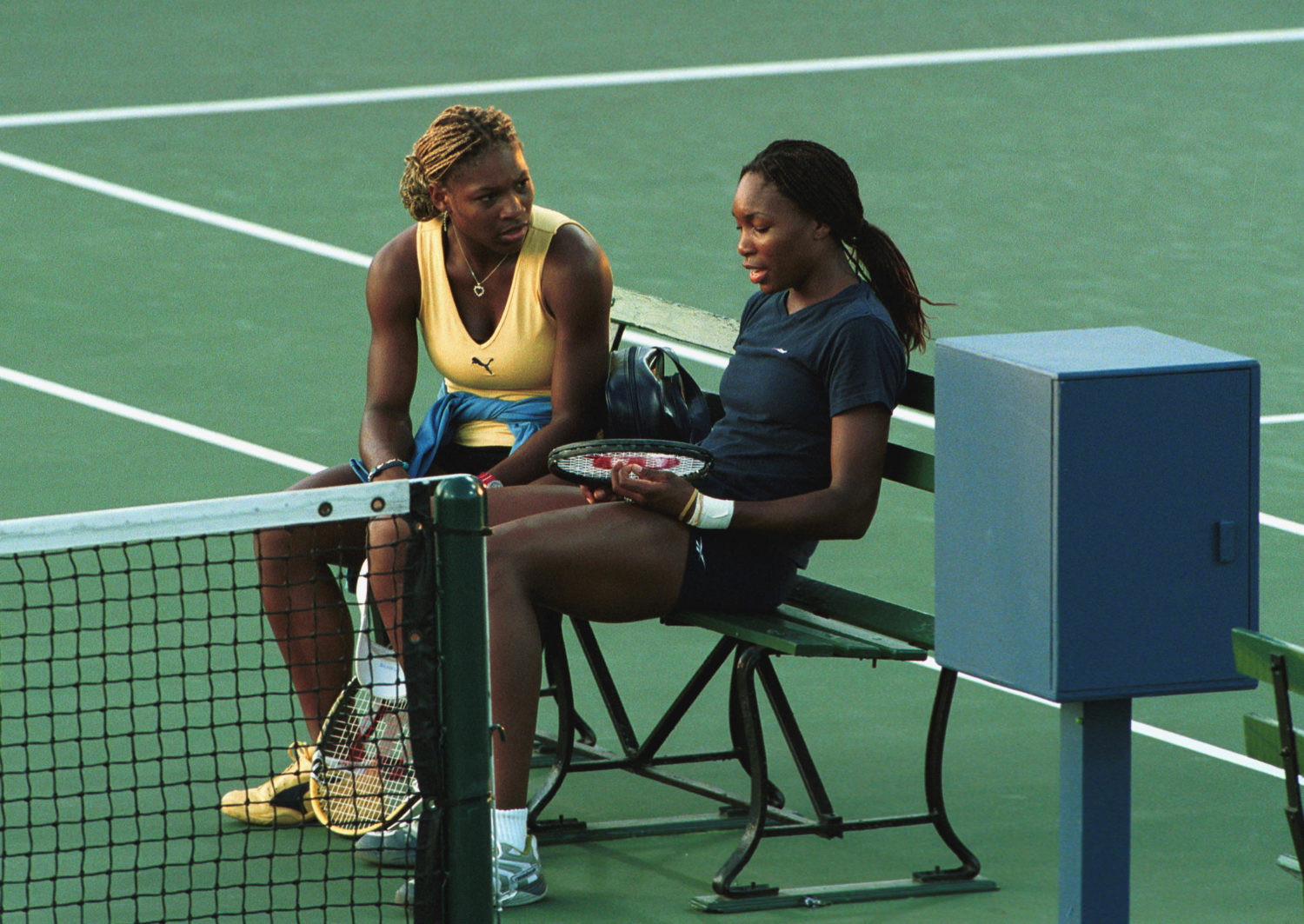

“From 1989 to 1994, I was photographing the Australian tournaments during the summer season. I’d done the Sydney Open, the Davis Cup, and the Fed Cup. Through that, I’d met a lot of the local greats like Ken Rosewall, John Alexander, John Newcombe, Lew Hoad, Kim Warwick, and such. In between tournaments, they would call and ask me to photograph corporate days that they were involved in. These were usually held at the White City in Sydney, the famous tennis club. You’d have executives from different companies, and all these coaches who were people such as John Alexander, Lesley Turner Bowrey, Kim Warwick, and Helena Anliot,” Ray says with a smile. “Remember her? A blonde girl. She was top-20 – Borg’s first girlfriend.” A mischievous grin appears on Ray’s face as he recalls a particular memory. “I’d get introduced as ‘Ray Giubilo, one of the world’s greatest tennis photographers’ and everyone was immediately impressed,” he laughs. “In the morning I’d take pictures of their lessons and drills, and at lunchtime, I’d go to the lab to develop the photos. In the afternoon, they’d play a tournament, and again, I’d take a motherlode of photos. Then back to the lab to develop them in time for the charity gala in the evening where I’d donate the photos. There would be an auction, and some of my photos would go for $5000. And I thought, ‘Wow’. I wouldn’t get the money, but that showed me the value of my work.”

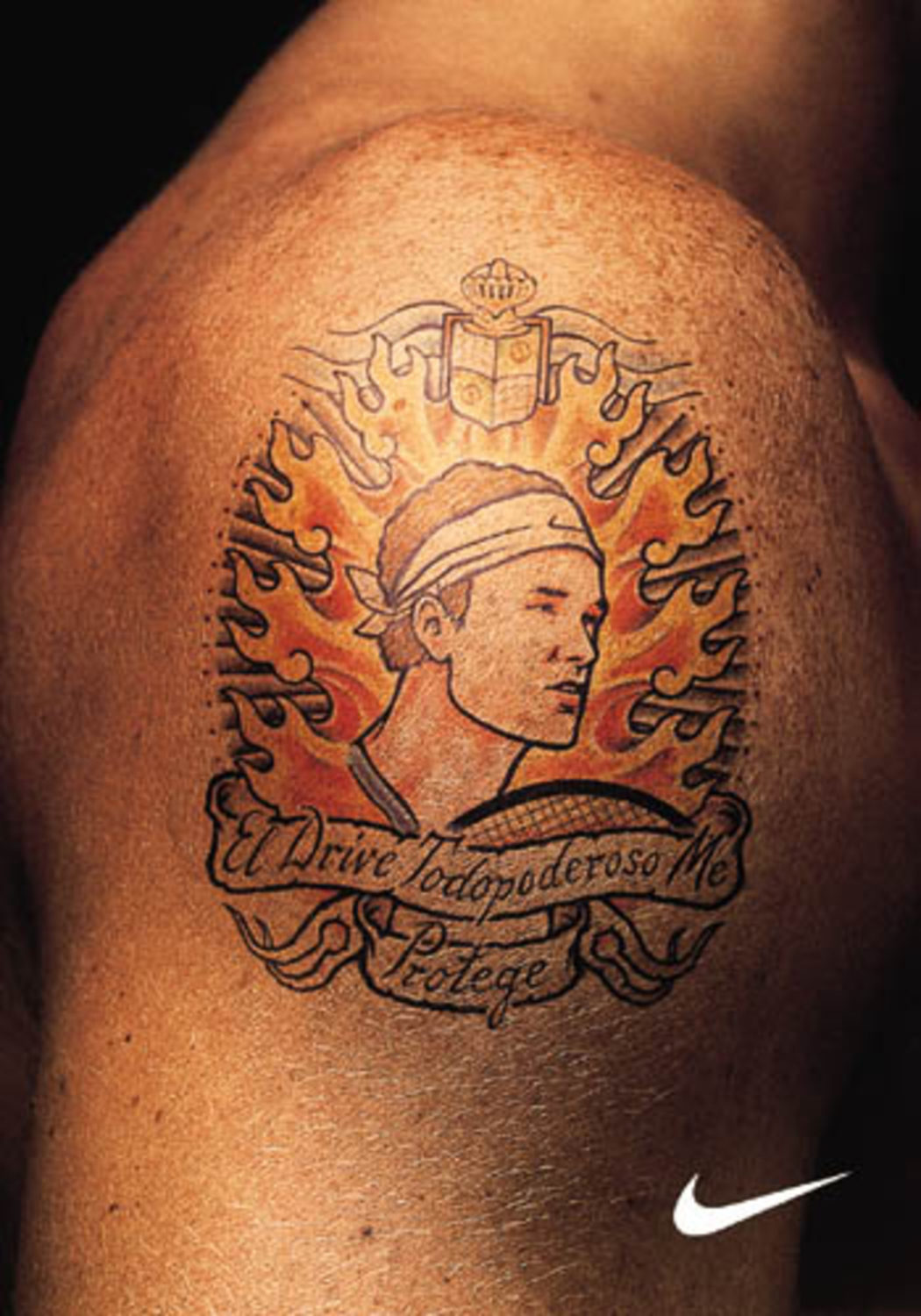

“I’d decided that I needed to focus on photography full time so I told Sergio Tacchini that I’m done with the clothes because I wanted to be taking photos. And he said, ‘Okay, the clothes are selling. How about if you take photos for us?’ And I said, ‘Wow, that is great. I’d love to.’ And he said, ‘Okay, so you would have to move to Italy, and you would need to be here in time for the French Open. We will give you two weeks to think about it.’ I said, ‘You don’t understand. I’m doing it.’ I got rid of everything in Australia. I sold the house, got everything sorted, caught a plane over to Italy and started doing the tournaments for Sergio Tacchini. Eventually, Sergio sold the business to a Chinese company and I moved on to begin a new adventure with FILA. They have always been my favourite tennis brand, and we’ve been working together since – over 27 years.

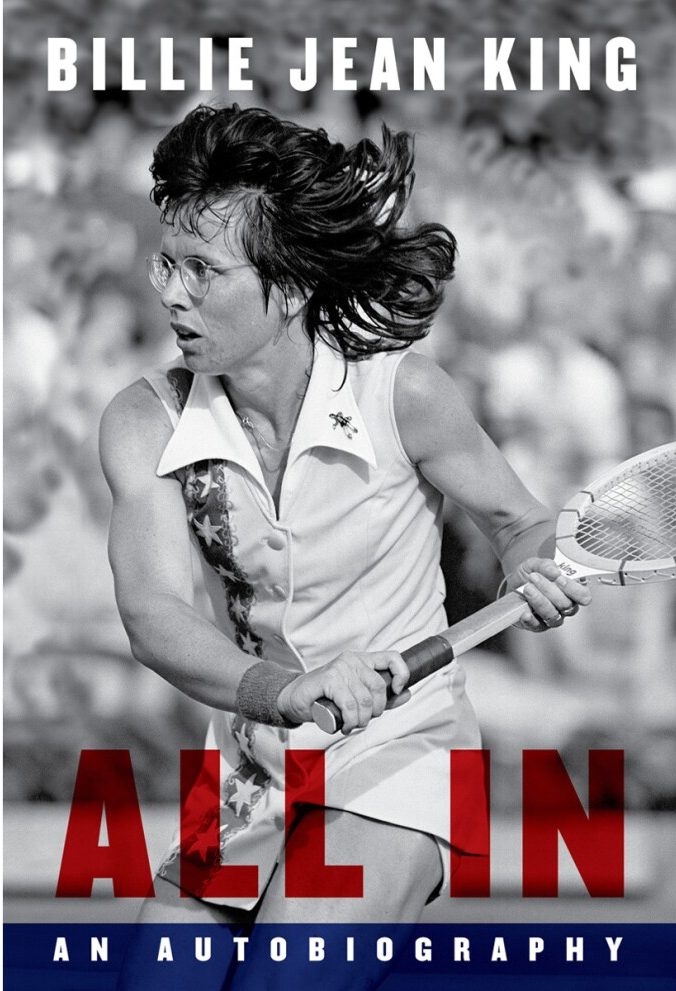

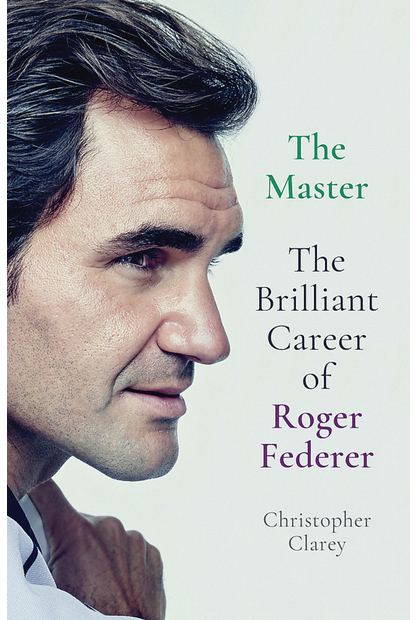

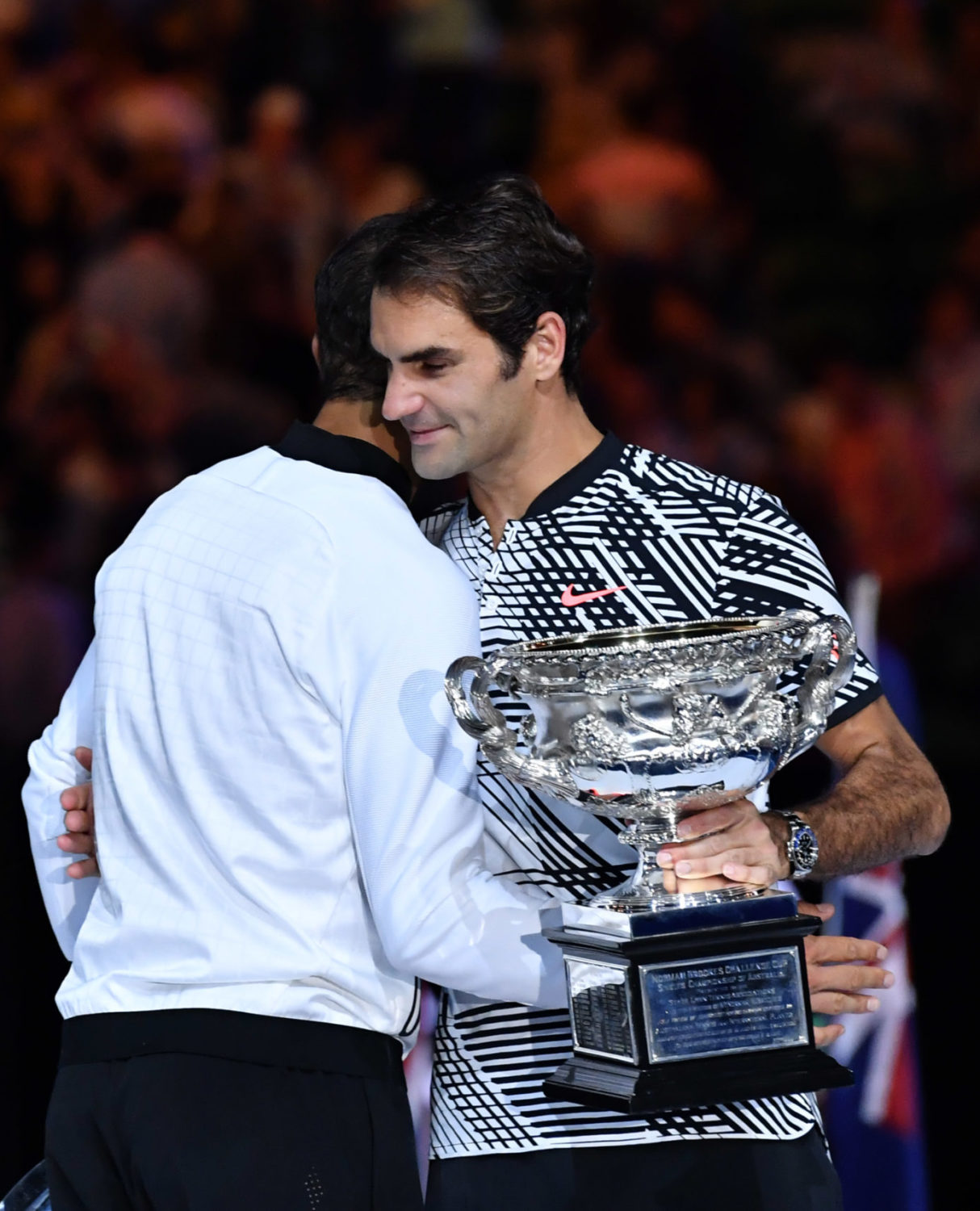

The conversation turns to tennis and, inevitably, to Wimbledon. As an accredited photographer, Ray has a first-row view of some of the best tennis in the world. I ask him about his personal favourites. “For me, Roger Federer will always be number one. I don’t think he’ll go too far here because Sonego will give him a good run [in fact, Federer would ease past Sonego without much trouble, but then suffer his worst Wimbledon defeat at the hands of 14th seed, Hubert Hurkacz]. And I saw yesterday [against Cameron Norrie] that after four steady backhands, he would mishit the fifth one. So he doesn’t have that confidence, probably, or maybe it’s even physical,” Ray says, and as he finishes the sentence, his eyes light up, and I know he has another anecdote for me. “One of the four photography books I wrote is about Federer, ‘Roger Federer, Il N.1 di Sempre’ (Roger Federer, Number One Forever),” Ray tells me. “And I met him when he was a junior. He was in Miami playing the junior tournaments, and he came into the press room where I was waiting for somebody else, so we were the only ones there. And so, this kid arrives – and I saw him lose in New York to David Nalbandian (US Open Boy’s Singles, 1998), the first time I saw him – so he walks in and he has bleached hair and a lot of pimples. He’s wearing a hat,” Ray recalls with a big grin on his face. “I took one picture of him and asked, ‘Can you take off your hat?’ and he goes, ‘Nah uh’. ‘Come on, just one picture.’ So, he takes off his hat, and I took a picture of him with pimples and bleached hair. It’s in the book,” Ray says beaming. “After that, he started to recognise my face slowly. I was there when he won his first ATP Finals in Houston. We were boarding the same plane, and I said to him, ‘You know, one thing I would like in the whole world is to have your backhand. How do you do it?’ And he looked at me very seriously, he thought about it, and said ’How do I do it? Well, I take the racquet back like this,’ and he started explaining it to me!” Ray laughs. “He had to think about it because it’s all so natural to him. He’s a fantastic player. I thought he would have retired after the 2012 Olympics. I was sure. But he didn’t. He started winning again, and went on to win two more Australian Open trophies. We had to revise the book and add another chapter,” Ray laughs.

We step out back onto the street. The rain has stopped, and we start along the wet pavement towards the Underground station. Tomorrow, Ray will be back on the grounds of Wimbledon to cover the so-called Manic Monday – the entire fourth round of both men’s and women’s draw in one day, a knock-on effect of the middle-Sunday – for the last time. Ray Giubilo has been photographing tennis players for over 30 years. A few years ago, he purchased a photo archive from one of his mentors, Angelo Tonelli. His combined collection now contains over a million photos from hundreds of different events. “I have drawers full of hard drives. I don’t even know what’s in there,” he admits. For Ray, photography is more art than craft. When he talks about it, he talks about passion. And yet, his interests are far more encompassing. Throughout his life, he has sought beauty on both sides of the lens – he is an avid music fan, enjoys soccer, plays tennis with his trusty Volkl racquet, and rides a motorcycle.

Before we say our goodbyes, I ask Ray about his plans. “After Wimbledon, I’m going to cover the Olympics in Tokyo. Then the US Open and the Laver Cup in Boston. I’d do the Masters in Cincinnati but the timing isn’t right – it won’t work with the quarantine,” says Ray. “But that’s in the future. Now, I’m heading to the Victoria and Albert Museum. They have an exhibition with the world’s oldest carpet – the Ardabil Carpet. Did you know that?”

Story published in Courts no. 2, autumn 2021.