Carlos Alcaraz

Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

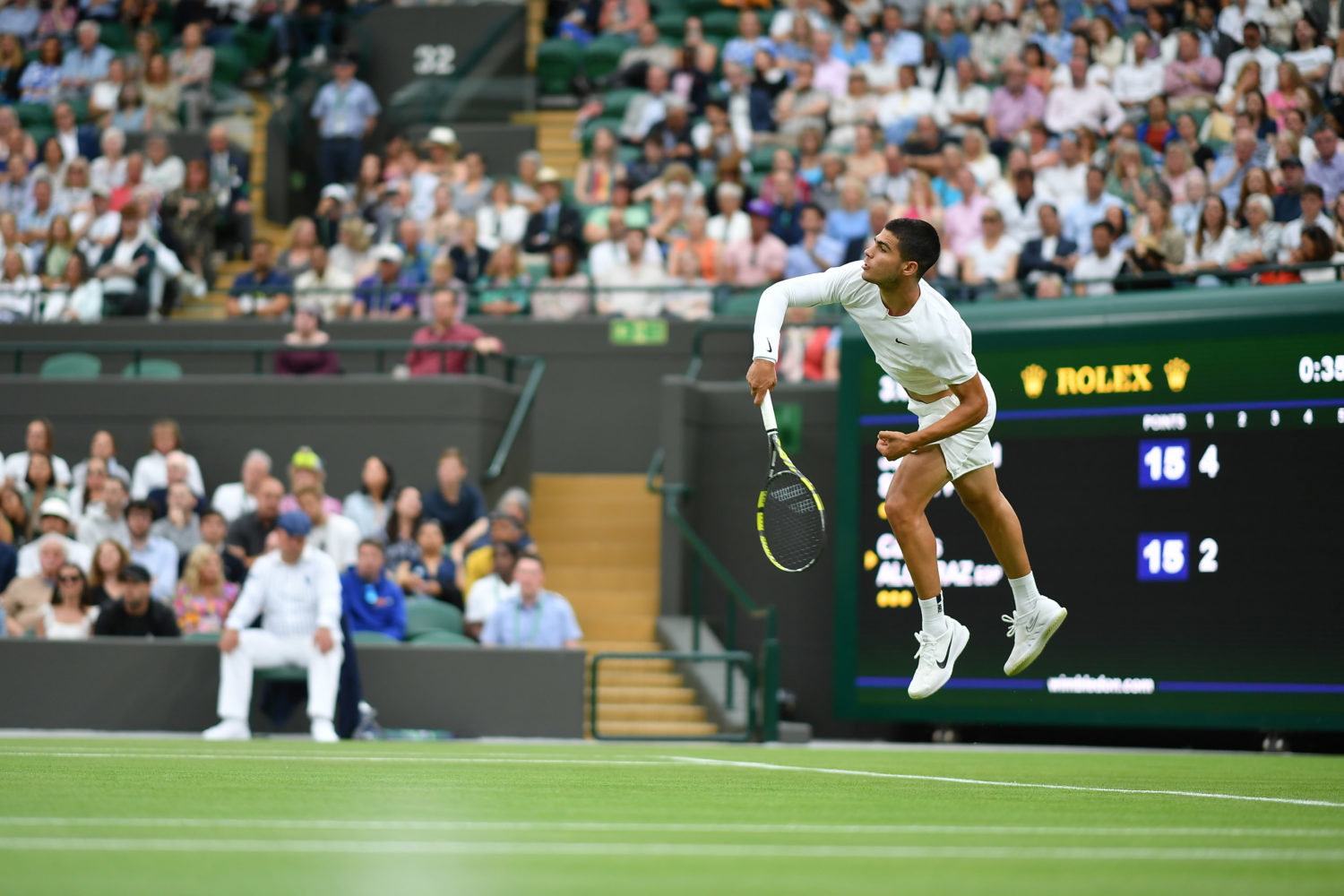

Carlos Alcaraz left his teenage years barely two months ago—yet it feels like he’s been a champion for a decade already. He can hit every shot in the book. He can win virtually every tournament, on every surface (except for Wimbledon, realistically, for now—cannot wait for him to prove me wrong). And when he plays his hypnotic brand of tennis, fuelled by an innate competitive drive—something about being born in Spain—he can lure every pair of eyes to him. As the pun goes, there’s no escape from Alcaraz. Already sitting at world No 1, with a Grand Slam and four Masters 1000 titles to his name, he’s both the present and future of his sport. He’s certified box office; he ticks every box, meets the criteria for every award category. Like the 2023 Oscar-sweeping movie ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’, Carlos Alcaraz may quite simply be the greatest watch in the world right now.

When I first saw Carlos Alcaraz in real life, at a junior Wimbledon tune-up event in Roehampton in June 2019, I wasn’t sold on him yet. Neither were some of the quiet club onlookers, one of whom telling me, with a sense of gravitas, ‘Heard he plans on turning pro after Wimbledon, that’s a ballsy move for someone who just turned 16,’ another hypothesising he might be ‘just another Spanish clay pony.’ A third opinion—rather an actual takeaway—stuck with me, though: The man in his corner was Juan Carlos Ferrero, who had briefly ascended to world No 1 in 2003, the year Alcaraz was born, and had turned down an offer from soon-to-become Wimbledon champion Simona Halep to take a leap of faith with the “next Spanish big thing”.

(Ferrero was my first joint-idol with Roger Federer: Clay-courter versus grass-courter, short-haired grinder versus ponytail-rocking serve-and-volleyer—I was going through a rebellious phase and ended up siding with the more badass.)

I guess Ferrero was avant-garde in his own right as a coach. What he saw in his young muse had to be backed by the deep-seated conviction that he would make him a star; not just a star, but the next world No 1. To make that bet, he clearly knew something we all didn’t yet. Could this frail, pimply-faced 16-year-old kid really be the future of tennis? After a few minutes, a thumping noise eventually broke my diverted attention, and that was my first encounter with Carlos Alcaraz’s magnetic forehand.

Ever since then, I have never looked away. Not when all COVID-19 hell broke loose just a couple of weeks after Alcaraz had claimed his debut ATP win at 2020 Rio, as if his rise was so rapid it had to be halted; not when the Tour restarted six months later and Jannik Sinner, two years his elder, made his case for leader of the Zoomers; not when Alcaraz was steamrolled 6-1 6-2 by spiritual father Rafael Nadal at 2021 Madrid Masters, on the very day of his 18th birthday, both a painful hazing ritual and a valuable learning experience—extraordinarily, he has yet to lose again on Spanish clay since that day; definitely not when an unseeded Alcaraz stunned No 3 seed Stefanos Tsitsipas 7-6 in the fifth in an electrifying 2021 US Open third round—the very last time the airborne Spaniard came into a match flying under the radar—on a dreamy summer day in The City That Never Sleeps, one that breathed 24 Alcaraz magic in the air, the first day of the rest of his star-powered life.

2022 would be his obra maestra, his master- piece; his definite coming of age. Fresh from his emphatic victory at the Next Gen Finals, an informal graduation from boyhood, a coping mechanism for a Paris humiliation to modest Frenchman Hugo Gaston, Alcaraz bulked like the Hulk over preseason and showed up at the Australian Open with the kind of silhouette only A-list actors can so quickly achieve. He was part of another 7-6-in-the-fifth third-round thriller, this time losing it to Matteo Berrettini, again stealing the highlight reel and enthralling the minds. In the next eight months, Alcaraz took me back to my own teenage years, doing things I hadn’t seen anyone do since the early days of Nadal and Djokovic, or ever, defeating both giants at the same clay-court tournament (Madrid) for the first time in their duopoly. While doing so, he carried himself like he owned the place, and when King Felipe VI personally went to congratulate him after taking down Nadal, one felt they were in presence of Spanish royalty—times three. Carlitos I would soon enough stand alone, atop the tennis rankings, and on the list of men’s tennis players to become world No 1 as teenagers. En route to the US Open title, he saved match point against Sinner in what went down as the best quarterfinal match I have seen in my life. After an underwhelming Roland-Garros, and facing the finest rival of his generation, it was a must-win match; by clinching it by the skin of his teeth, Alcaraz removed any last ounce of doubt in me, proving conclusively that he possessed that elusive X-factor—that he was him.

Beyond all the accolades and the history-making, what truly glues me to the TV is the way Alcaraz plays tennis, the very essence of his craft. He hits his forehand like a cannonball, whether it’s on the run or running around his backhand; when he does hit his backhand, he either anchors himself into the ground or seamlessly slides into the open stance; he follows his shots up to the net with intent and confidence, because he so often chooses the right time to put down the hammer, and he does it with iron hands in a velvet glove; to mix things up and “never let ‘em know his next move,” he unleashes his signature, lethal weapon: the drop shot, generally used after a string of cannonball forehands. Powered by a gifted eye, his returning is elite; powered by tireless legs, he can retrieve every ball, sometimes disappearing off the screen and reappearing in a cloud of smoke, or clay—to quote Pedro Almodóvar, “My special effects are my actors,” aka Alcaraz himself. Like Almodóvar’s cinema, he’s exciting, yet diabolically efficient. He’s made for this decade, and the next. He has the complete package. In fact, his arsenal of intangibles is so well-rounded that it makes up for a serve he still has to perfect, the only shot in tennis one can truly master, the only one he hasn’t truly mastered yet.

In the midst of the Alcaraz craze, a Tennis TV graphic showed him in a science lab alongside the Big 3 of Federer, Nadal and Djokovic, suggesting he might well be a combination of all three divine elixirs. At the risk of exposing myself to popular vindictiveness, I believe there’s an element of truth in this. Federer was his first idol, and he picked up his immaculate forehand technique and his appetite for the net; Nadal was his role model, and he picked up his fighting spirit and his sportsmanship; Djokovic was the most complete, the most ahead of his time of all three, and he picked up his backhand, his tennis IQ, his percentage-game philosophy and everything else. Like so many all-time greats, Alcaraz defines himself as an assiduous student of the game. Growing up in the 2000s and 2010s provided him with the best possible case study over two decades. When watching him in the present era, such as in his methodical, wholehearted demolition of Daniil Medvedev (6-3 6-2) in the 2023 Indian Wells final, you get a glimpse of the future as much as subtle flashes of the past, as if playing in a Stephen Hawking-developed tennis space-time continuum.

When I watch Alcaraz today, I often circle back to Ferrero’s tears of joy when his pupil won his maiden Masters 1000 title in Miami in 2022—the tears of someone who reaches their Eureka moment, who realizes they have been so right about something it actually hurts. When I watch Alcaraz today, in all his teenager-just-turned-adult-but-having-almost-everything-figured-out glory, I often circle back to that morning of June 2019 in Roehampton, and I think to myself it was right before my eyes—The Theory of Everything, Everywhere, All at Once.

This article was originally published on tennismajors.com

Story published in Courts no. 4, Summer 2023.