Pistol Pete

When Pete Sampras eked past Pat Rafter in four tough sets to win his 13th slam title at a rain-ravaged Wimbledon in 2000, it was difficult to overstate the enormity of the moment. The wait for Sampras to usurp Roy Emerson and claim the title of all-time slam record holder had been long and fraught. For 12 years, Sampras had dominated men’s tennis in a way that had never been seen before.

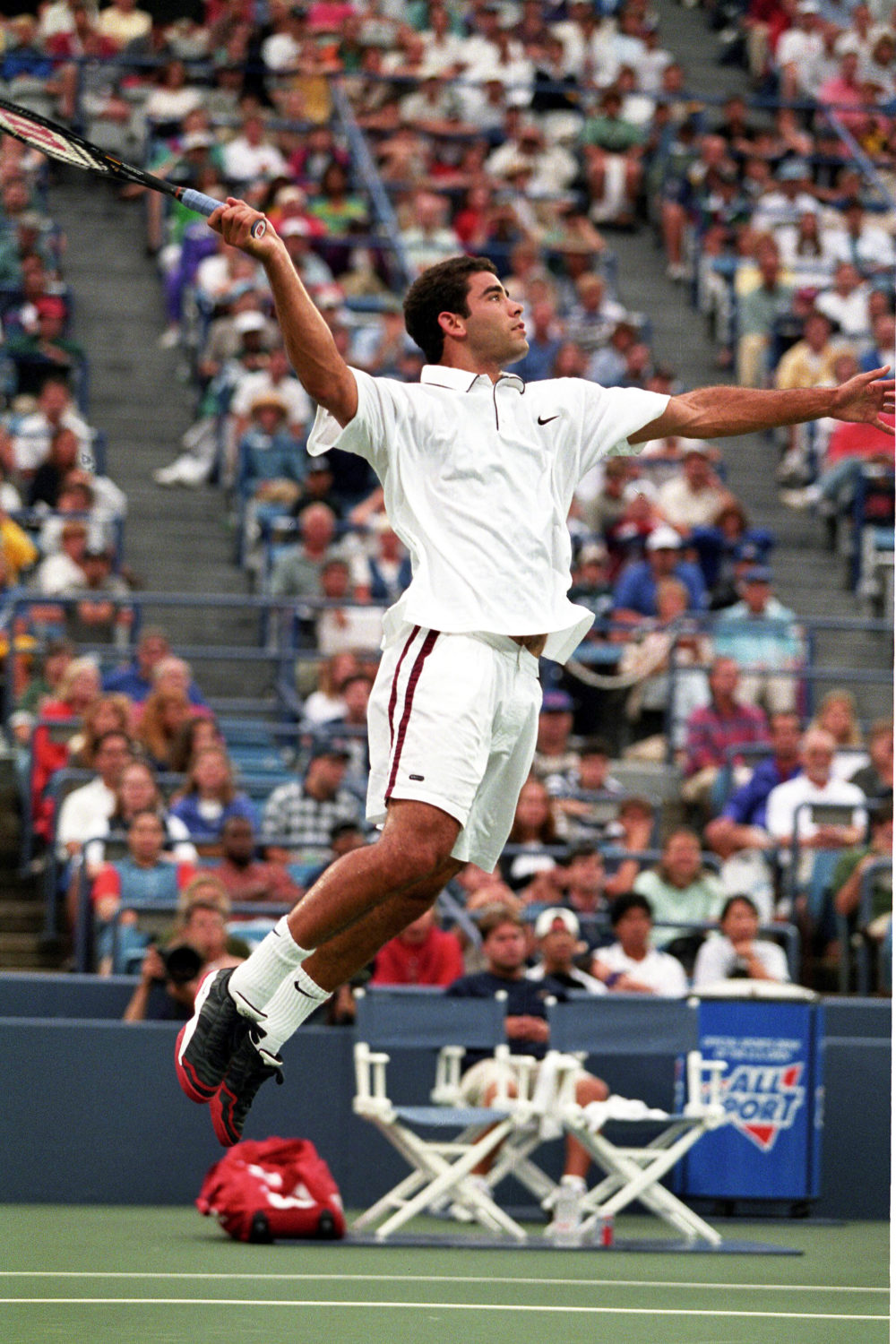

Everything great Sampras achieved began with the delivery. From the way he bowed his head forward, readying his lethal aim, to a second delivery that was nearly as good. Behind the most devastating serve in sport, he constantly moved to the net and ravaged opponents with his running forehand. His success championed the rise of the Wilson Pro Staff, as fans rushed to buy it in the hope that some of his magic would rub off on them. Alone on the court, in some of the most pressure-filled moments an athlete can face, his blood ran cold. Tennis has the ability to drive its subjects mad, but for over a decade he made tennis look easy and his demeanor suggested that it really was.

For much of the ‘90s, Sampras’ greatest rival was Andre Agassi, an equal in talent and by far his superior in bombast and celebrity. Together, they produced one of the great sporting spectacles, but even their battles were deceptive.

Their games seemed to present the perfect contrast. Not the typical fire and ice, but two aggressive players tearing the opponent apart in completely different ways. Agassi owned the baseline and his return, Sampras served flawlessly and flitted to forecourt at every opportunity. They were built up as equals, but after their final match, when Sampras surprised the world to capture his 14th slam title at the 2002 US Open, Sampras left with a 20-14 lead in matches, 6-3 in slam events and with 14 slam titles to 8. Pete Sampras had no equals.

After his victory at the 2002 US Open, as he spoke of the adversity he overcame and his refusal to listen to the press as they wrote his career obituaries, Sampras was asked about the future of his seemingly impregnable record. He shrugged.

“Time will tell if it will be broken,” he said. “I think in the modern game, it could be difficult. It’s a lot of commitment, a lot of good playing at big times. You know, it’s hard to see one guy or three guys that I see maybe doing it. It’s possible. I mean, the next person might be eight years old hitting at a park somewhere around the world. You never know.”

Three slams after Sampras’ final US Open triumph, Roger Federer won his first Wimbledon. Nobody could have imagined that as Sampras relaxed and enjoyed his retirement, the rare times he resurfaced in front of big crowds would be to watch in person as Federer, then Rafael Nadal, and then Novak Djokovic eclipsed his records with seeming ease.

The luster of legends always fades a little with time. Human beings forget easily. The current era of men’s tennis has accelerated that process, redefining the record books and completely altering how the sport, and what is possible within it, is seen.

It sometimes seems like the memory of Sampras’ playing days was most affected by the rise of the big four, because they arrived so soon after his premiership ended. But it is important to never forget the Greek-Jewish American who had the audacity to play how he played and do what he did, a player so great that he was able to engineer the greatest curtain call, defeating his truest rival one last time in the final of the US Open before departing into the night and never looking back.