Tennis Charisma

Who are the players who knock your socks off? The ones who, the moment they walk onto the court, have you in another world? The tennis stars whose presence makes the game everything to you, transfixing you totally? It is not just skill—not a question of perfectly executed groundstrokes or the fastest serve ever or perfect footwork that always has them where they should be. It is a very particular phenomenon:

Their talent seems to have been conferred on them by some divine force. Their charm compels us. Those of us who were never groupies for rock stars and who rarely succumb, are happily transformed.

What makes these players magical has no metrics, no qualifying characteristics. It is what happens inside you when those athletes have their rackets in their hands. “Knock your socks off” is a very particular expression. I recently explained it to one of my wonderful French squash-playing friends. I was quoting a florist in rural Ohio. I had phoned to order a bouquet that would surely bring delight, even amazement, at a party being given for my wife, a professor of writing at a college in the middle of farm country. I could not attend because a lecture commitment on the wrong side of the Atlantic made it impossible, but I wanted her to feel my love at that very moment, to compensate for my absence. And, yes, I wanted to make a public display that would make people say “Wow!”—that would startle them to happy awareness.

I named a figure that I wanted to spend on “an incredible bouquet.” It would, I was told, comprise of fresh-cut stems from a local farmer who would harvest the most glorious blossoms of that spring morning from the fields where they would just have been blooming. The amount of money I said I would spend was not exceptional by Paris standards for a centerpiece on a banquet table. It was, however, clearly more than this florist had ever been offered except for an entire wedding.

I could hear the florist’s smile on the other end of the phone. “That’ll knock their socks off!” she exclaimed excitedly. But the term needed a lot of explanation to my Paris pal sitting outside the squash court with me while we took a break between a couple of happily intense sets. He repeated it with French diction “ka-noque your soques awff.” It was worth trying to translate, because it takes us into the realm of impossible delight. It is worth summoning because it applies to tennis players who have an effect on us that is so totally, and pleasantly, irrational that it equates to someone managing to remove your socks without actually pulling them down off of your feet.

The older you get, the nicer it is to remember some of those unequivocal states of rapturous admiration, and the sense that you might grow up to ascend to the heights you are witnessing, that you knew as a kid growing up. Cases of worship for your hero as someone you might grow up to emulate. Later in life, you have players who blow you away, but most of us, when we were discovering the game of tennis, had heroes who were also role models: our fantasies of whom we could make ourselves. They are part of the glory of sports executed not just with skill, but with style.

You will know my age when I say that my friends’ heroes were Mickey Mantle or Ty Cobb. The first is easy to understand. Mantle was not just a superlative first-baseman and center fielder, but was also a brilliant switch hitter (meaning an ambidextrous batter, as it did back then, not a bisexual as it does now.) The New York Yankee triumphed in spite of living with the after-effects of osteomyelitis and then an accident during a game, but he stayed humble and welcomed rookies warmly even as he was considered the top of the top players. But the adulation of Ty Cobb seems perverse. I mean, sure, Cobb’s number of runs batted in and winning plays as an outfielder—and lots of other Major League records that he holds to this day—make him a ballplayer without equal, but to love a player known for cursing, for slugging other players on and off the field, and for temper tantrums is particular. Cobb claimed that the source of ferocity was that he needed to win to impress his father, who was killed by Cobb’s mother with a pistol he gave her. Cobb claimed, “I knew he was watching me.” Yes, Cobb had machismo, and skill, but how my childhood friend could swagger around our elementary school playground imitating that famous “poor sport” and exalting him as a hero makes the adulation of Ty Cobb a clear case of deliberate mischievousness.

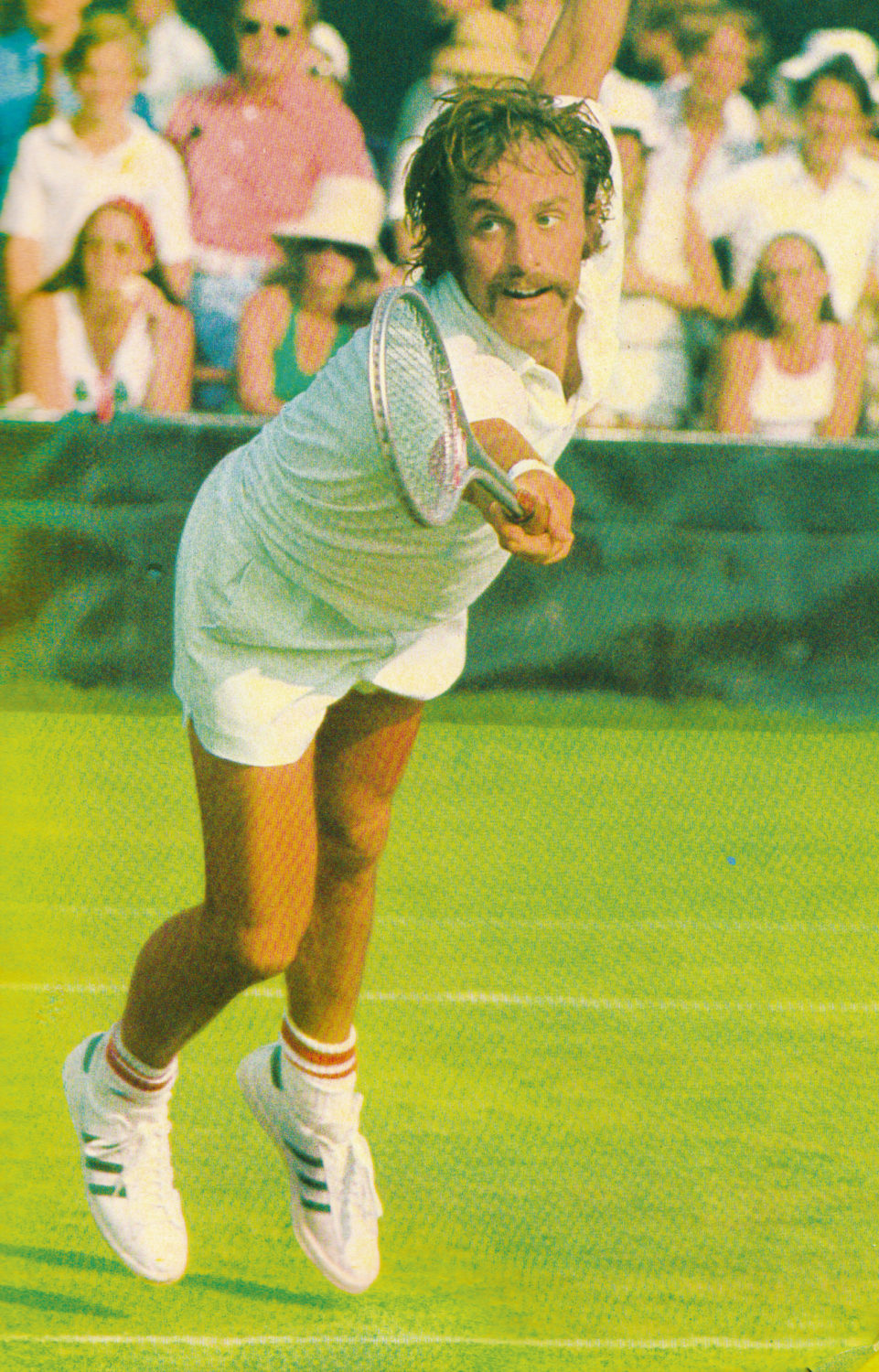

My worship, meanwhile, was the tennis player who was, quite simply, like a Greek god: swift of foot, light in spirit, classically handsome, and personally possessed of perfect standards of behavior. John Newcombe was the player I loved to watch and wanted to be.

How many of you know his name today? Well, you know the name James Bond. Bond was the other hero figure who made me a total wannabee, and the two had similar degrees of charisma and magical capability. A “wannabee” is someone who desperately wants to be something or someone, who aspires to the heights embodied by others, and he or she feels the pull intensely.

With James Bond, however, you see it all—not just the ability to vanquish every rival and escape every danger, however close to the edge he is, but also the romantic conquests, the suavity with which he downed those stirred not shaken martinis. With Newcombe, I only saw him playing tennis, but that was all it took: this guy epitomized life lived to the highest degree, unfathomable skill, and charm radiating out of every pore.

I had seen him from afar at Forest Hills, and on the big old television set that was one of those early behemoths with a curved screen and a plumpness and weight that made it the foil to Newcombe’s Greek warrior litheness. But the clincher for me was when I was able to stand courtside when he practiced for an indoor tournament in Hartford, Connecticut. I was older by then, and I knew that there was not a chance of my becoming a serious competitive tennis player, just an ardent enthusiast of the sport I still love. Still, seeing Newcombe put me in the state of little-boy adulation again. Every forehand was a masterpiece, executed as if by an expert stone carver taking his chisel in and out with millimeter-perfect measurements. Every backhand rendered complexity seemingly simple the way that a leap by Rudolph Nureyev did. The serve! Most tall people seem slightly bowed by their height. Not Newcombe. He rose onto his toes and extended his arm to the fullest height, the racquet meeting the skyscraper of a toss at the perfect moment to send the ball soaring to its precise target on the other side of the net, at whiplash speed. His volleys, lobs, and overheads were textbook-perfect. He moved like a gazelle. But that wasn’t the thing. It was the charm, the something extra, the injection of aliveness: the constituents of charisma.

I will never forget Newcombe’s response when his opponent laced a driving forehand to the far back corner of the court so that Newcombe could not even dream of getting to it. First he smiled with sheer admiration. Then he put down his racket so as to have both hands free to applaud. It was more than class. Yes, I make comparisons to John Kennedy; these are people who inject life with grace.

The thing is: no one calls Newcombe the best player ever. Yes, he won Wimbledon, and garnered his share of major trophies, but he’s never Number One on anybody’s list. Maybe that is part of what makes him, still, so real, and so likeable. What he doesn’t have in hardware (my favorite term for sports trophies,) he has always had in charm. Look at that smile! See those crow’s feet alongside his eyes; they have the look of life really lived. The guy sparkles. And it isn’t just that his glistening teeth accented by the dapper mustache belong to a gladiator; it’s that added something, the sheer panache.

Facts are often surprising about our heroes. Newcombe stands to six feet, and was born in 1944. So now I learn that the guy who is only three years older than I am, and two inches taller, seemed like a nimble giant, the epitome of maturity and savoir-faire to the teenage me worshipping him at courtside. A tennis aficionado who follows the statistics might comment that the only detail where Newcombe was “best in show” was his second serve that was an ace more than the usual number of times, but maybe that detail sums it all up: just when you thought he could not do it, he pulled out the miracle. How James Bond! To be down after missing the first serve, which is like having the villainess standing with her dagger at your throat, and then not just to escape, but to vanquish the force that had you at knifepoint with a clear, clean, can’t-even-touch-it victory! The guy wasn’t just your usual good tennis player; he was a sorcerer.

Yes, Cyrano de Bergerac!

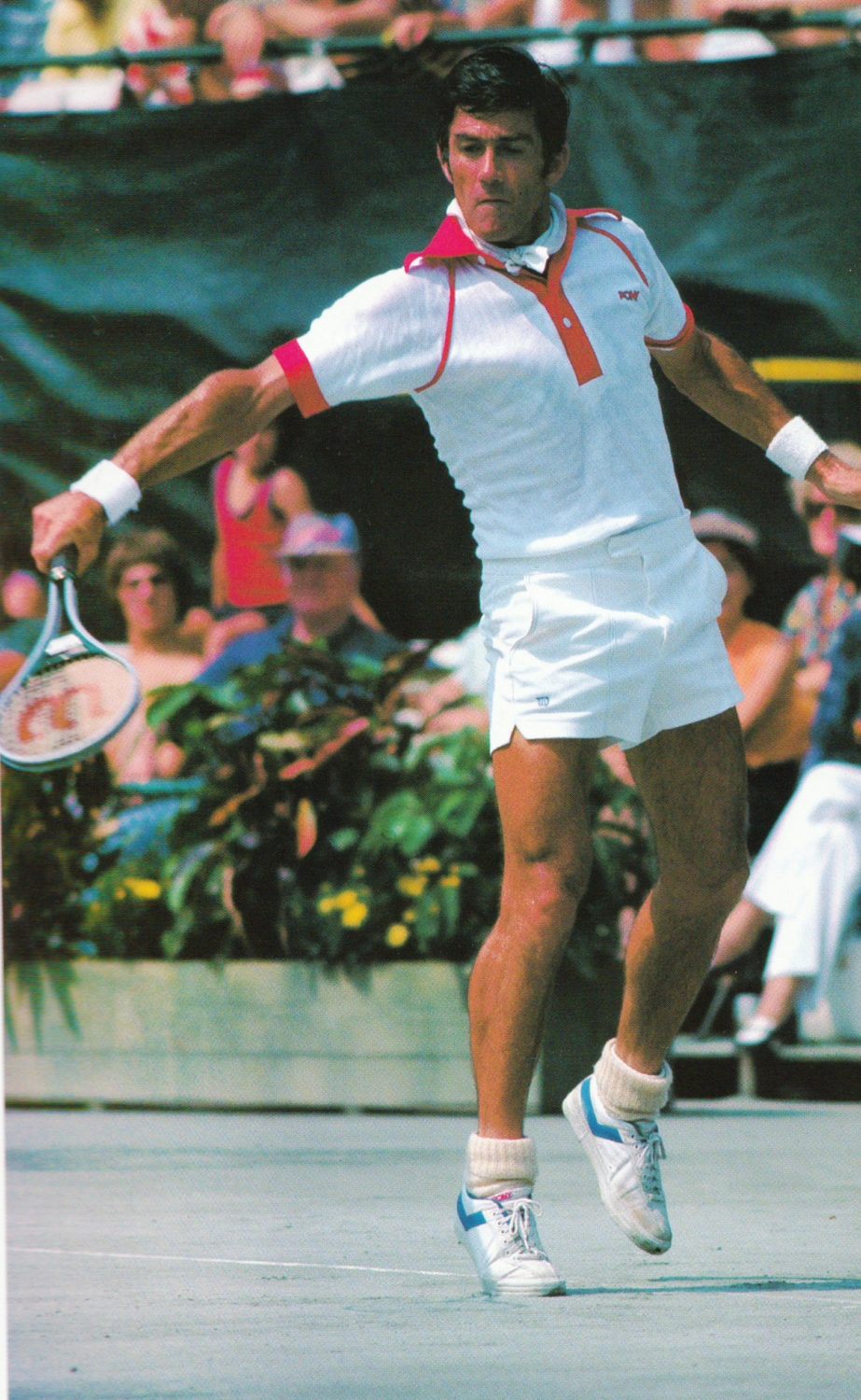

And who else has had that something extra, that charisma that is not just excellent, but that is charm and humor on top of pure excellence. Our tastes are personal. For me, the one today is Rafa. Nadal is both a tennis player par excellence and a boxer so nimble and concentrated and strong that he leaves me wowed. Is this because at age four I was taken to watch Rocky Marciano practice in the ring and then he signed my boxing glove? (Oh, where is it? But the things that disappear from our childhood must never get in the way of the memories of sheer thrill, of the feelings that live forever even if the objects don’t.) The way that Rafa is a new person for every single point. That concentration that is like a blazing sun, and the bit of mystery that makes him the El Greco of tennis players—a personal style all his own, an artistic polish with sheer out-of-the-ballpark originality.

I know of a surgeon at the Mayo Clinic who says that Nadal’s court performance is his guiding light in his work in the operating room with the patient before him. What gets to this skillful doctor is not simply the way Nadal gives a hundred percent once the ball is in play. It is also the relaxation between points. To be so totally on, one has to have the capacity to turn it off too. The surgeon learned long ago that if he allows the hectoring administrators or the subalterns with irritating questions to get to him when he needs to unwind rather than get wound up even tighter, he could not master his craft. Nadal is the exemplar: breathe deeply and calmly, with no intrusions, when you do not absolutely have to be present to the nth degree, and you have what you need to summon at the right moment. That, too, is one of the reasons JFK caused the word charisma to enter everyday parlance; he had the light touch, the insouciance, the sheer no-pressure charm that enabled him, when the situation was urgent, to have all the steel and vigor he needed.

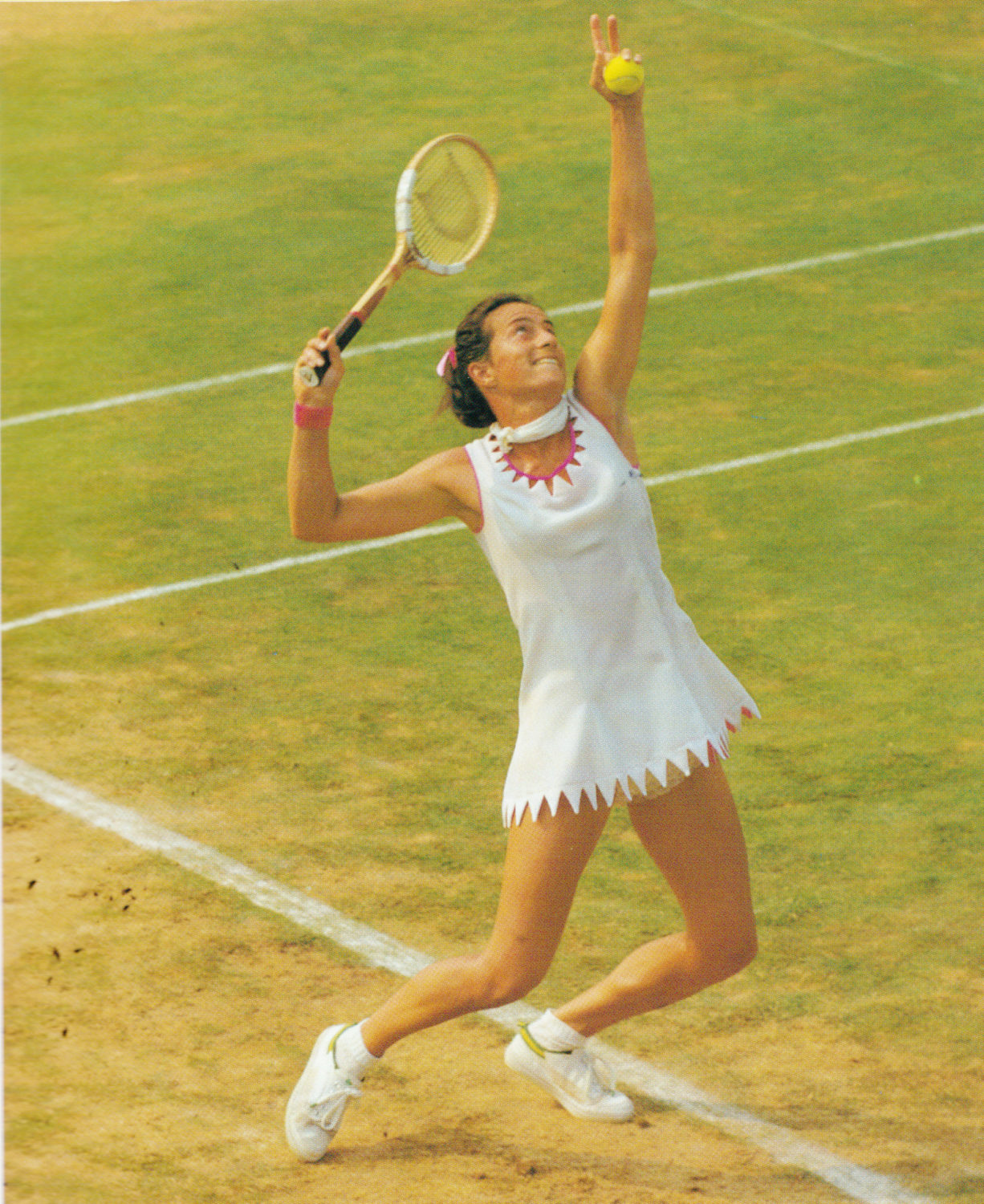

And who got to me among the great women players? Sure, when I was first taken to Forest Hills, my father looked as if he would melt into the bleachers when Maria Bueno walked onto the court. Her subtle pink cashmere cardigan over her whites when she sat sweetly after a victory was the coup-de-grace of female beauty. As a kid, Bueno’s allure caused my first alertness to the fire that burned inside my puritanical father, a quietly lusty and sensuous man presenting himself as a sort of upright Yankee businessman. It took a tennis player to make him drop the mask; he managed to keep the façade even when Gina Lollobrigida was on the screen. Maria’s mix of skill and sheer grace was his undoing.

But for me, and you may find this odd, but passion, and the pull of charisma, know no logic, the first to get to me was Virginia Wade. This may strike many of you as an odd personal taste. Sure, she, like Newcombe—they are almost exactly the same age—has won an impressive number of Grand Slam titles, including Wimbledon during the year of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, which was also the hundredth anniversary of the tournament. But those are facts, and facts are not the point. Wade always projects a daunting intelligence. Maybe this is because, at the height of her tennis power, she resembled Virginia Woolf—not just because they were both Virginia W’s, but because of the sheer intensity and patent thoughtfulness. The dark hair, black before it was salt and pepper, and those strong blue eyes convey stature. But, beyond that, the daughter of an archdeacon and mathematics teacher, brought up in vicarages, was high strung and volatile and could not conceal it. She spoke like the educated person she was, and was deemed haughty by other players, but that mix of genuine class and the fire within was, at least to me, irresistible. She was visibly high-strung, volatile, and charged by nervous energy, but the results of what others deemed uncouth and aggressive paid off beautifully—in damaging forehands and backhands that were, if merciless, triumphant.

But the moment I became irrationally enchanted by Wade was when I read that, to relax between matches, she tended to read Henry James novels. That in itself is not charisma, but in my eyes Wade became one with some of James’s most intrepid and independent female characters. Yes, she is, and always has been, a woman on her own—private, publicly solitary—while showing a skill and a staggering talent that surely could have minions surrounding her if she wanted. She has a bit of the silence that gave Oriental emperors and empresses a power that no amount of rhetoric could ever have conferred on them. She is not “a type.” She never groaned; she never showed off. She just exemplified quality, and correct comportment without a hint of snobbiness. It gives a mysterious allure.

We all have our own superstars. What graces them all, though, is that extra something: the consuming drive that elevates our tennis heroes to the pantheon of greatness. One can sharpen and refine and master those strokes, but, with charisma, a handful of legendary players have been the people Robert Browning had in mind when he wrote that our “reach must exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” That drive to perfect oneself is part of charisma; add charm and wit, and the pleasures abound.

Article publié dans COURTS n° 5, été 2019.