The Tennis Court Is Home

It provides reassurance and memory, the ideal essence of what “home” should be. The moment you arrive, you are on familiar ground, the single place in your life to which you have always gone and can always return.

It never changes, wherever you are in the world. The layout is invariable. The length is 78 feet, the overall width 36. But if you look for a precise system—everything divisible by 2, or one dimension being twice the other, or repetitions in series—it is more subtle than that. Yes, these two numbers are divisible by both 2 and 3, but the 21 feet from net to service line is a multiple only of 3; the same applies to the 39 from net to baseline, and the 27 that is the width of the singles court contained so neatly within the doubles. Those measurements impart a sense of rightness but also an essential sense of variety.

It is all so heartening and so centering: the way the court is what it is, unlike anything else but true to itself whether it is surfaced in clay, grass, asphalt, or Astroturf. The scheme is, of course, a mirror image, the net its perfect divider. This exactitude is part of what makes you know yourself when you are there, whether it is an autumn day in Norway when your fingers are so cold that you can barely grip the racquet, or a sweltering one in Dakar when you are so soaked with sweat you wonder how you will ever get your shirt off afterwards.

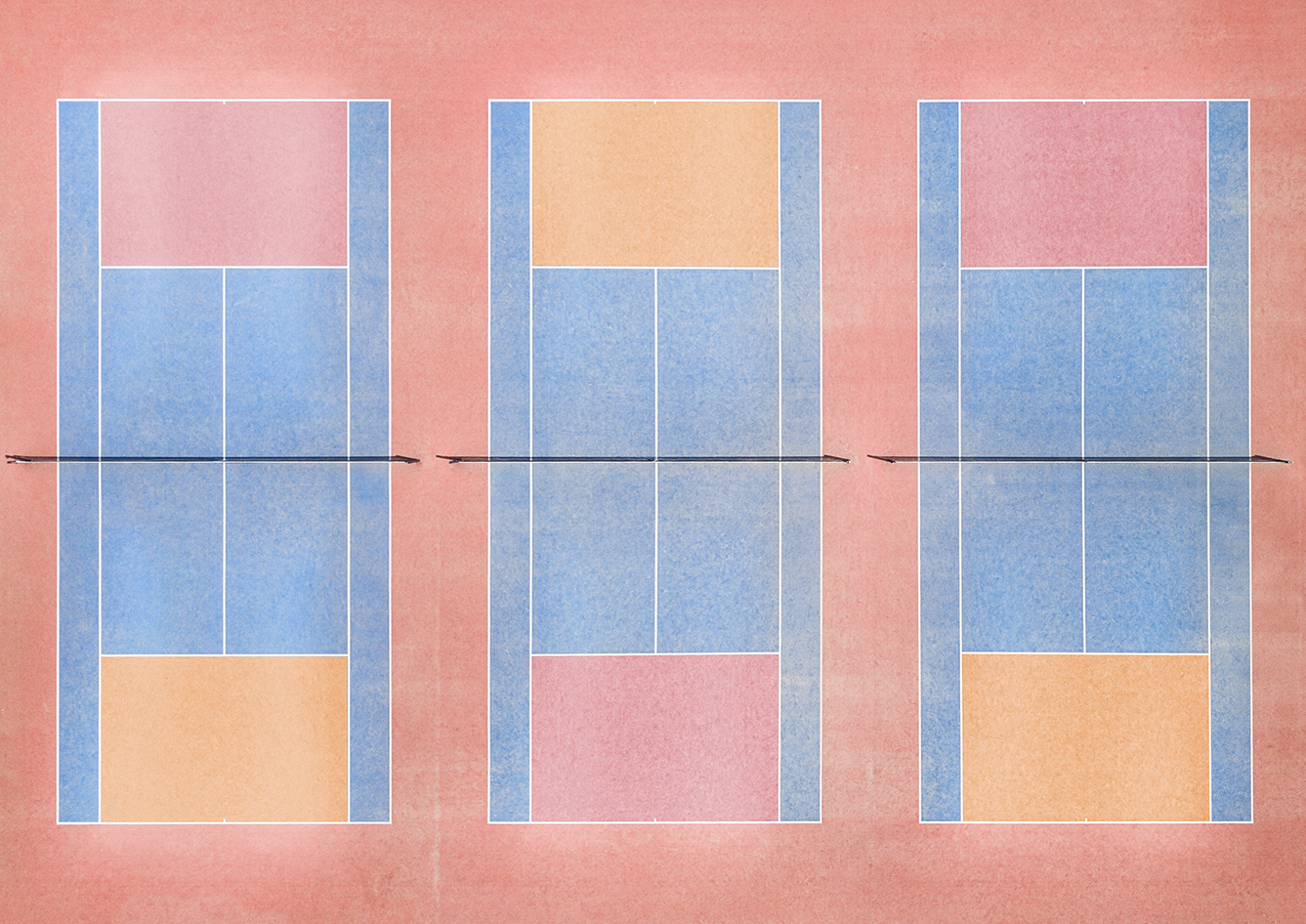

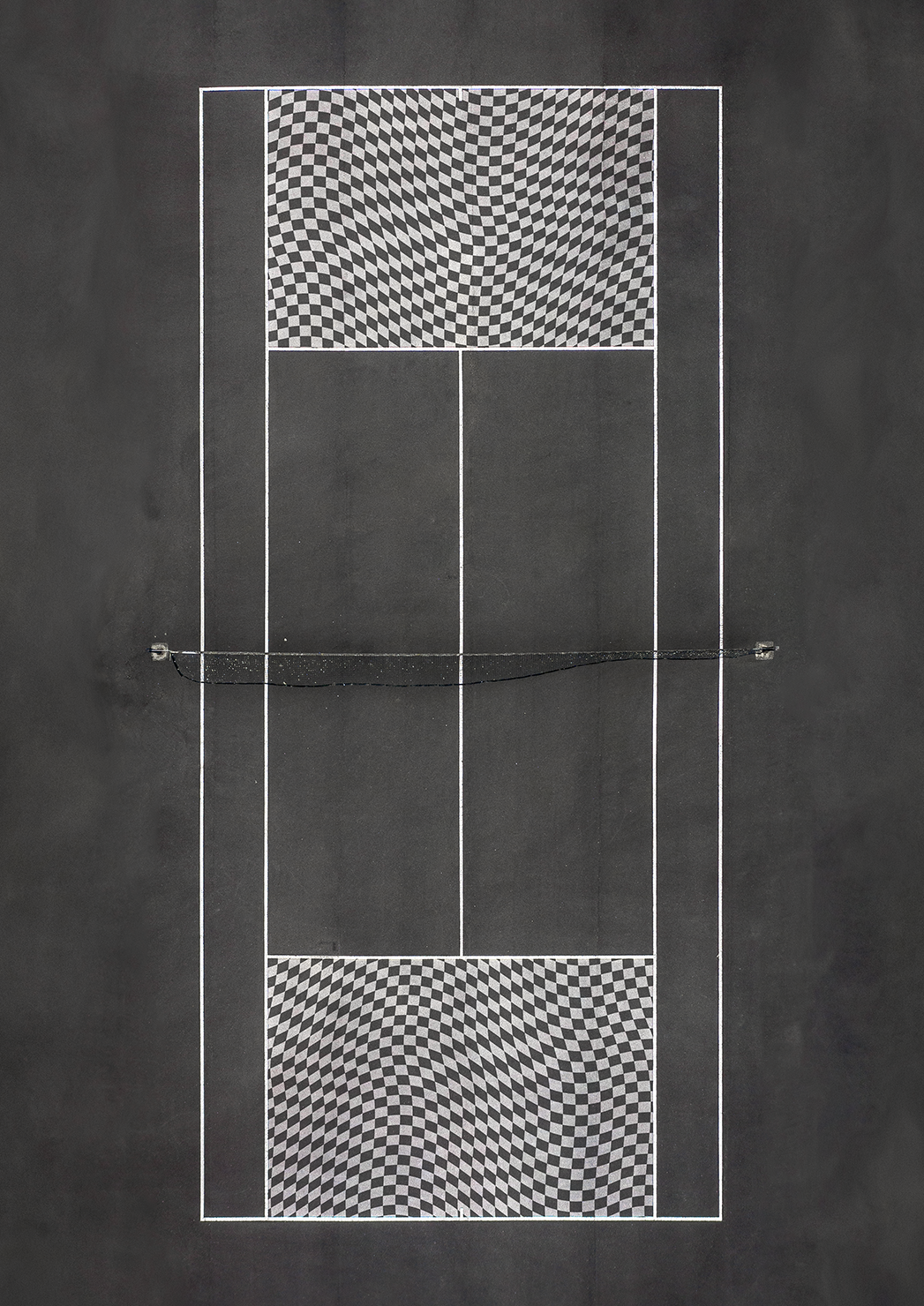

The great abstract artist Piet Mondrian reduced his paintings to pure, straight verticals and horizontals, and impeccable right angles; he eschewed diagonals as disconcerting outsiders. In tennis, too, when you stand there before play begins, diagonals belong only to the action that lays ahead. For now, there is stasis. You can hardly wait to angle those shots, to lace a crosscourt backhand at a sharp trajectory, to vary your serves unpredictably from one back corner to the other of your opponent’s receiving area, but when you arrive, you start with the calm and sense of inner balance that comes because of the flawless grid.

Mondrian never played tennis, but he loved to dance the foxtrot, and whether he did it in his native Holland or a Paris nightclub or a New York ballroom, its basic box step gave that same sense of “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.”

As the home to which you can always return, knowing that everything is as you remember it—and, moreover, will always remain that way—the court is the great mnemonic. As a septuagenarian who has played since the age of eight, I never know which memories will come back suddenly, or at what moment, or what inspires them. But there they are. Last week, I suddenly remembered games with my friend Ricky when we were teenagers, playing in the public park, and all we really wanted to do was listen to and look at the slightly older girls who also played there, especially the affected one with beautiful black hair and a glorious figure you would say “Your ad” in a way that sounded like “You’re odd.” I knew her name was Myra, but nothing more, but I can still hear that voice and picture the sullen way she stood when receiving. When I play, wherever it is, on days when the air is especially cool and crisp and clear, I am back on summer afternoons at Tamarack Tennis Camp, the haven where I worked every summer during my college years. There were nine red clay courts in a valley cradled by mountains, and all the kids and teachers wore whites. I can feel the fun of rolling the courts, of spreading calcium, of sweeping them, and then, the final glory, the wonderful way that single strokes of the small broom brush off the powdery clay you have just swept on to the lines with the large yoked broom unique to tennis. Order has been restored; the surfaces are again ready for play, the lines crystalline. I can picture Mrs. Whitehouse Walker, the dowager grandmother of one of the slightly aristocratic campers, arriving in her Ford Mustang and declaring, in her flowered summer dress, “The air is so pure you could drink it!”

At any location and in any conditions I periodically imagine the voice of my Cameroonian friend Pierre Otolo urging me not to stop the stroke before a full follow-through—“Laisse partir, Nicholas!”—even if I am a thousand miles away. We all have our own encyclopedia of memories that come back when we stand on the court that always provides a homecoming.

How trustworthy those 2808 square feet are! In Quito, when I was fifteen, on a summer trip that started with a coup d’état and a curfew where we were told that if we were still in the city we risked being shot, the court from which you could see volcanoes was such a comfort. With the altitude, it took a while to get used to the way the ball bounces so much higher than at sea level, and the sprint to net initially leaves you more breathless than you are used to, but, still, the court was a safe harbor. When my wife and I went to Guangzhou fifteen years ago, and I said I would go to the public park and see if I could drum up a game, I managed, while not speaking a word of Cantonese, to borrow a racket and have a wonderful game with someone who only knew of me that my name is “Nick,” and I of him that he was “Pang,” and that our common language was tennis. Still, we knew what the score was although we said it differently; we smiled and implicitly congratulated one another on shots well hit; we shared the pleasures of a lively game, surprisingly equal for players who had only just met by chance; and the universality of a lot in life, and tennis in particular, struck me deeply.

Yes, the tennis court is not only home: but the home that both cossets us and allows us, securely and happily, to spread our wings.

Story published in courts N.6, autumn 2019.