Dressed to Win

“You-ah shortah than he is, and he is tallah than you-ah, so you two change seats. Move to wheah he is, and then I will be able to see–at least slightly bettah.”

She did not say “please.” And it is impossible to capture her accent phonetically, because no one else except for her sister—Marion Ellsworth, also a tennis player—spoke in that particular mix of upper-class London and New England Yankee, and with that deep voice and unflinching sense of authority.

I did not have to turn around to know that the woman instructing us was Katharine Hepburn. And my wife, another Katharine, and I did exactly as commanded. The curtain would soon be going up in the ornate Victorian pile of a building with its wedding cake architecture on the Connecticut River—the Goodspeed Opera House—and it made sense that the great nonagenarian actress was there, since she summered in Fenwick, an exclusive coastal enclave nearby. Still, as the heavy folds of deep red velvet rose ceremoniously under the ornate gilded arches over the stage, I was totally surprised when those two small feet in short white athletic socks appeared on each of my wife’s shoulders, the heals firmly planted and the toes pointing upwards.

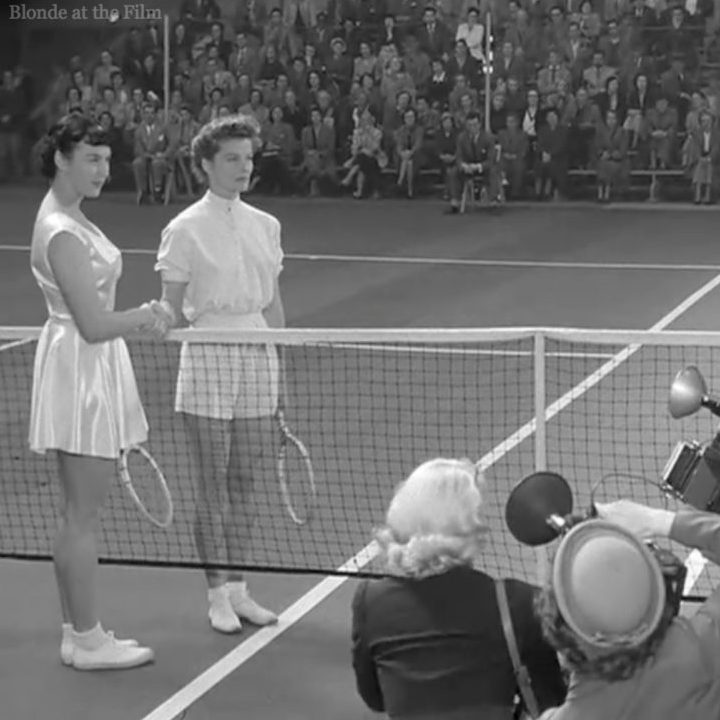

Now, two decades later, I have had another surprise. Thanks to my engaging in the sort of expansive project encouraged by the innovative and delicious COURTS, I have discovered that those bobby socks were part of a major fashion statement. Katharine Hepburn had, in the great 1952 movie Pat and Mike, changed forever the way that women could—at least in what is known as “good society”—dress for tennis. The cushioned socks that only went up the ankle a couple of inches were part of the deal.

The movie, directed by George Cukor, was written by Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon, friends of Hepburn and of Spencer Tracy. It was created specifically to showcase Hepburn’s tremendous skills at both tennis and golf. As Pat Pemberton, the actress played both sports superbly, and her radical attire added to the panache. Women like Hepburn’s mother wore long white skirts which they had to hold up so as not to trip on the hems when running around the court. Until Hepburn wore shorts in Pat and Mike, female players were always in tennis dresses, albeit shorter than in earlier years and easier to play in than those outfits that looked like ball gowns had been.

And what shorts Hepburn wore! They were very high-waisted, and just about as short as is physically possible. She had the thighs that enabled her to carry them off perfectly, which patently had inspired her decision to wear them; as I knew from the presence of the little foot about six inches from my right ear, Katharine Hepburn did not do timidity. If you are lithe and leggy, let the world know it.

Her top in Pat and Mike had a high crew neck and pockets with flaps that buttoned over each of her breasts, about as provocative as a relatively flat-chested woman could be. But what she was flaunting was nothing like what other actresses of the era put on view—if you consider the likes of Marilyn Monroe and Rita Hayworth. Hepburn was showing herself to be audacious, original, and determinedly athletic. This was clothing in which you could really play the game at your best. At the same time, it was extremely well-designed, the sportswear equivalent of Balenciaga or Chanel. Style and skill were in tandem.

Pat Pemberton’s combination of athletic prowess and personal allure were irresistible in the film, a wonderful Hollywood bit of fun. Pat’s fiancé, uptight and omnipresent, gets on her nerves whenever she is competing, since he hopes she will throw in the towel, marry him, and settle down. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy—Hepburn’s love in real life—plays the spicy, colorful Mike Conovan, a sports promoter who isn’t above working with mobsters. Those tennis shorts hiked above her midriff, and the exceptional top, are all part of what makes Pat exactly the sort of rebellious woman one finds irresistible. They augment her attraction to the bad-but-not-too-bad Mike. Throw in cameo roles of Gussie Moran, Don Budge, and Alice Marble—tennis greats of the epoch, dressed more traditionally—and you have a world-class romp. The tennis scenes were shot at The Cow Palace in California: the perfect setting for the great actress/athlete to do her stuff. And the real appearance of the champions of the era added to the “wow.”

So there I sat, Katharine Hepburn’s left foot on Katharine Weber’s left shoulder, so close that at least I could be certain it was odorless. Even if I did not realize that those feet on my wife were part of the actress’s chic, what I did know is that I could pay no attention whatsoever to the first act of the play being performed. I sat there thinking, “Those are the feet that went down the river with Humphrey Boggart in African Queen.” In white bridal shoes, they led the hungover Tracy Lord up the aisle of the church in The Philadelphia Story before one of the single most charming moments in the history of theatre, with the bride first saying that she was not marrying the intended groom, and then, when prompted, announcing his replacement with the same man she had married once before.

My wife felt she had earned the right to speak during intermission to the woman who had used her shoulders as a footrest. She thanked her first for her generosity to Planned Parenthood, causing the infamous Kate to bellow, “The problem is the goddamn Catholic church!” Then Katharine Weber explained that, when making sure that people spelled her name correctly, she referred to Miss Hepburn. The actress simply asked, “Were you named for me, deah?” The response that KW was named for her grandmother, the great composer who was professionally Kay Swift but whose real name was Katharine Faulkner Swift, did not interest the gal who broke barriers with her tennis clothes.

Women’s tennis clothing had come a long way between when females started playing the sport in the 1860’s and when Katharine Hepburn donned those shorts to be seen bare-legged on movie screens all over America and much of the rest of the world. At first, female players had almost their entire bodies covered. In order to have the right shape for their long-sleeved blouses with collars that went half way up their necks and long bustle skirts, they bound their bodies in tight, hard corsets underneath. The undergarments constrained them, but comfort and ease were beside the point; you would not violate the dress code any more than you would grunt the way players do today. Whatever the heat and humidity, the dress material was heavy. Flannel and serge were the norm, sometimes with fur. Most of the outfits included neckties, perhaps because they were de rigueur for men as well. And skimmer hats were essential—these being straw boaters with very wide brims, often with colorful bands.

The more colorful, the better—as is true again today, albeit in tight Lycra, the hues shiny, rather than flowing wool in muted but lush blues, mauves, and golds. That changed only in 1884—at the Wimbledon Ladies’ Lawn Tennis Championship. Maud Wilson won the event wearing solid white. Her bustled two-piece dress, so long that it flowed along the grass as she ran, looked as pure as snow.

Who among you can imagine the reason that white remained in vogue from that moment forward?

It was not a matter of style or of regulations. People wore white because it did now show sweat stains the way that colors did. One would have thought that a change of material would have been considered important, but elegance mattered more than comfort in the tennis of earlier eras.

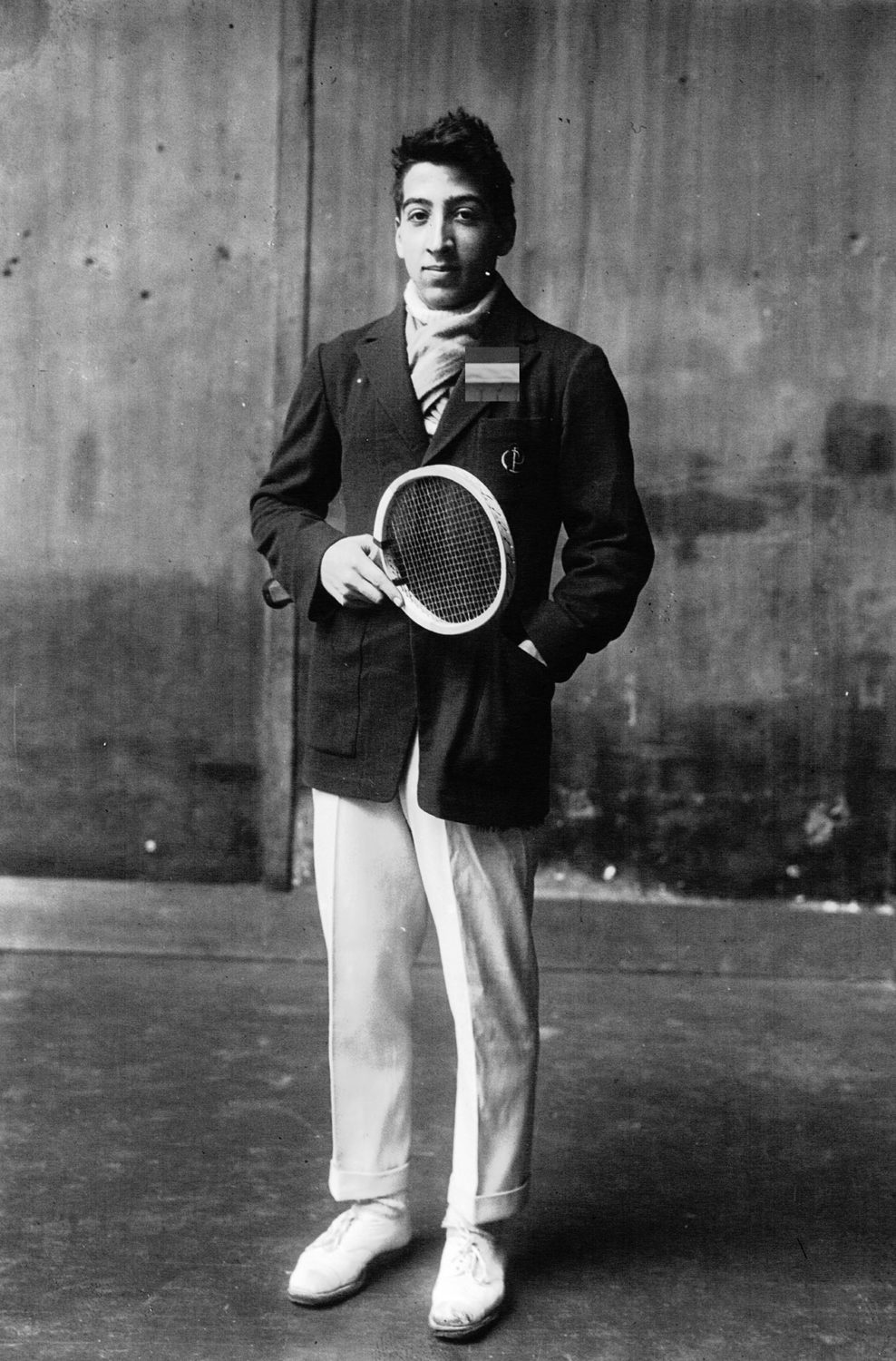

For men’s tennis, the player who set the benchmark of style, never to be equaled, was René Lacoste. He cut a figure of fantastic elegance on the court well before he developed the eponymous shirt with its reptile logo that symbolizes power and cool, and the wearing of which makes someone feel like an insider.

The earliest pictures of Lacoste show him with a fantastic foulard sweeping up his neck like merengue, flowing out between the lapels of his blazer as if to say “I am here to enjoy myself, no restraints; I will live the way I play tennis, with style and unbridled spirit.” The boldness of this neck covering says, much as Roger Federer’s backhand does, “Tennis is not just about fitness, tactics, skill, or coordination; it is about style. It demands courage. We need to go to the outer limits of what is possible. We are not just athletes; we are magicians.” Perhaps the term “ascot,” or quite simply “scarf,” would be more apt for this item of clothing Lacoste has knotted and puffed as no one else in the world has, but “foulard” is the one of choice because it conjures a material that is light and flexible. Its weightlessness and ability to move like air itself are also the quintessence of a beautiful serve, or of an effective rush to the net—as they are of fine silk.

Whether Lacoste was what you think of as “handsome” is, somehow, secondary. His looks were swarthy. With straight and richly black hair, and a nose that is brazenly there, he was, by European standards, exotic. Tennis may have been considered Anglo-Saxon; in his visage, René Lacoste certainly was not. But his clothing changed the game—it altered both his persona and the sport of tennis itself.

A history of tennis clothes would be one thing; to consider their impact, depending on the style of the era and the individual who wore them, is another. You will never see another blazer that fits like the one sported by Rene Lacoste in a photo taken of him off the court when he was eighteen years old. Today’s players would be wearing “warm-up jackets”—functional synthetics—while what Lacoste has on to keep his muscles from getting cold and tightening, either before or after the match, is a masterpiece of haberdashery. It manages to be, at the same time, tailored to his body, and almost billowing in its looseness. The terms used by fancy menswear designers—“English fit,” “unstructured,” “formal,” “casual,”—all apply. They are contradictory, of course, as is the way the blazer buttons, which makes it seem both double-breasted, or what the French call “crossover,” and single-breasted. How perfect for a tennis master who could hit his groundstrokes flat, sliced, or with topspin—always unpredictably. To have it all in your bag of tricks is, after all, the essence of good tennis.

Lacoste, born in 1904, had developed all those skills and more by the time he posed for that photo. It all began for the native Frenchman in England. When he was fifteen, he accompanied his father on a trip there, and picked up a racket for the first time. He was a quick learner, playing at Wimbledon a mere three years later.

He had earned the right to look like a potentate, as he does facing the camera. The racquet is here simply a symbol, held at the throat rather than on the grip, his left hand in his pocket like a real country gentleman. We know he has his work uniform underneath. He wears immaculate white tennis shoes (we simply cannot say “sneakers”) and long, cuffed, slightly baggy white pants. It is their length that identifies them as short enough by Savile Row standards to be positively inacceptable—like the trousers of a boy who has shot up four inches since he bought them—for anything other than sports.

In the greatest tournament in the world, Lacoste lost in his first round that year, but the following year made it to the fourth, and also to the US Open.

From there, victory followed victory. In 1925, Lacoste triumphed at both the French championships and Wimbledon, garnering singles titles as he would continue to do, on and off, for years. He beat the likes of Jean Borotra, Bill Johnston, and Bill Tilden. He won some and lost some, and did his country proud in the Davis Cup. People called him “the tennis machine.” He generally stayed on the baseline, hit his groundstrokes deep, and was so methodical that he kept a notebook that recorded his opponents’ weaknesses.

As he began to pile up the trophies, Lacoste, already interested in clothes, wanted to refine his own. Ranked number one in the world in 1926 and 27, winning Grand Slams, he wondered why he had to wear the long-sleeved shirts, cut pretty much like those men wore with suits—except that for tennis they were button-down, presumably to keep the collar tips from flying outwards as the players ran—as well as neckties and long trousers. He noticed a “friend”—not just any friend, but the Marquis de Cholmondeley, whose name and social position made the way he did things instantly acceptable—wearing a polo shirt while playing tennis. Lacoste thought this infinitely practical.

He decided to have some polo-style shirt made, just the right way, by his English tailor, both in cotton and wool. This was before the era when we get silk and linen and cashmere blends, the percentages identified on their fancy labels, or “breathable” synthetics or shirts that are guaranteed to have so many properties, either to retain heat or let out perspiration or whatever it is, that you cannot possibly remember which shirt to wear for which weather conditions. What mattered most to Lacoste was to be able to run more easily.

The style of shirt worn in India by British polo players in the Victorian era had been made in America ever since John Brooks, grandson of the founder of Brooks Brothers, had seen them worn by polo players in England at the end of the nineteenth century. The short sleeves were a blessing. So, too, the tail that was supposed to keep the shirt tucked in at the back while it let in a bit of air, invisibly, in front. America was the place to try it. In the days when Brooks Brothers only had a couple of flagship stores—large ones in New York and Boston—whatever it did had style and a pedigree. The great painter Winslow Homer never left his studio in Maine except for the two times a year that he went to Boston to update his wardrobe at Brooks; what the store sold was not only acceptable, but aesthetically on the money. René Lacoste first wore a polo shirt on the court at the 1927 U.S. Open, and the rest is history.

In time, Lacoste married a golf champion, had children, and, when his health took him out of tennis competition, went into business. It’s the clothing and accessories that make the business the international success it is today, but in 1961, their key product was the racket Lacoste invented, the first ever made with tubular steel instead of wood. Wires were wrapped around the racket head, making it a powerful weapon.

And now, the question:

Alligator or crocodile? Surely this is one of the most hotly debated of all subjects concerning clothing logos of every sort. Art historians would call the issue an example of iconographic vagary, while kids and adults and the millions of other people interested either in tennis or clothing or, quite simply facts, all seem to be astonishingly certain that they have the right answer—whichever of the two reptiles he or she names.

Here is what the company’s website says:

“On a trip to Boston in 1923 with his Davis Cup team, René Lacoste saw a suitcase made of crocodile. ‘If you win the match, I’ll get one for you,’ his trainer, Alan Muhr, said ironically before the game. That anecdote gave birth to the name ‘The Alligator’ that appeared for the first time ever in a newspaper article in the Boston Evening Transcript, and that became the symbol of the brand.”

So it was a crocodile that begat the alligator. Except that Wikipedia calls the man himself “The Crocodile.”

Where does that leave us?

Indeed, in Boston, Lacoste was called “the alligator.” In France, he became “le crocodile.” In his obituary, his son explained that a friend of Lacoste’s embroidered a crocodile onto a blazer Lacoste wore over his tennis clothes. Yet why do some of the company’s advertisements, in English, make the key words, “See you later ….”?

A proper history of tennis clothing would fill an encyclopedia. An informative and entertaining one. The point here is only, with Katharine Hepburn and René Lacoste and a couple of others, to explore the impact of the clothes. Consider the outfits worn in sixteenth century England by the dudes—and I do mean dudes—who played the French invention of jeu de paume at Hampton Court. They looked like courtiers jousting. The word “swashbuckling” was rarely more apt. With long hair, pageboy-style, they resemble confident, athletic hippies—the sort of easy going rich kids some of us envy on the ski slopes as they zoom by confidently. You have to be very manly to wear skintight jackets with white ruffles billowing out of the collars, around the shoulders, at the elbows, and around the synched waists, but these fellows carry it off with aplomb. The tight breeches, possibly suede, rolled up just over their knees, make those very tight tennis shorts worn by players like Jimmy Connors and Ilie Năstase seem loose-fitting; your butt has to be just the right shape if you will play an active sport in these. But these guys carry it off, and so, with the clothes, an utterly fascinating, entertaining, beautiful sport, one that requires consummate skill and that affords unique pleasures because of the particular movement of those heavy woolen balls and the range of surfaces off of which they bounce unpredictably, becomes that much more pleasurable.

Walter Clopton Wingfield, the Welsh army officer said to have invented lawn tennis, wore incredible outfits. What gives them such distinction is that they are dashing without being the least bit foppish, making tennis a manly sport as splendidly as the long flowing dresses and floppy hats and delicate blouses worn by some of the female greats make it a feminine one. Wingfield favored doublets, snug and without sleeves, of gorgeous thick fabric with a complicated weave, attached by silky embroidered buttons. He would have the sleeves of his loose-fitting cotton shirt rolled up above the elbows, his bulging forearms on view, thus defining himself as someone who was both a true aristocrat and a tough guy, who followed the rules of style but did what it took to be physically at ease so he could win the game. He wore his beret at the perfect jaunty angle, had his neck scarf tied à-la-militaire, and kept his handlebar mustache and pointed beard in perfect trim. At the same time that he was such a well-clad specimen, he had a body like an American football halfback’s; that combination of worldliness and brute strength would surely intimidate any opponent.

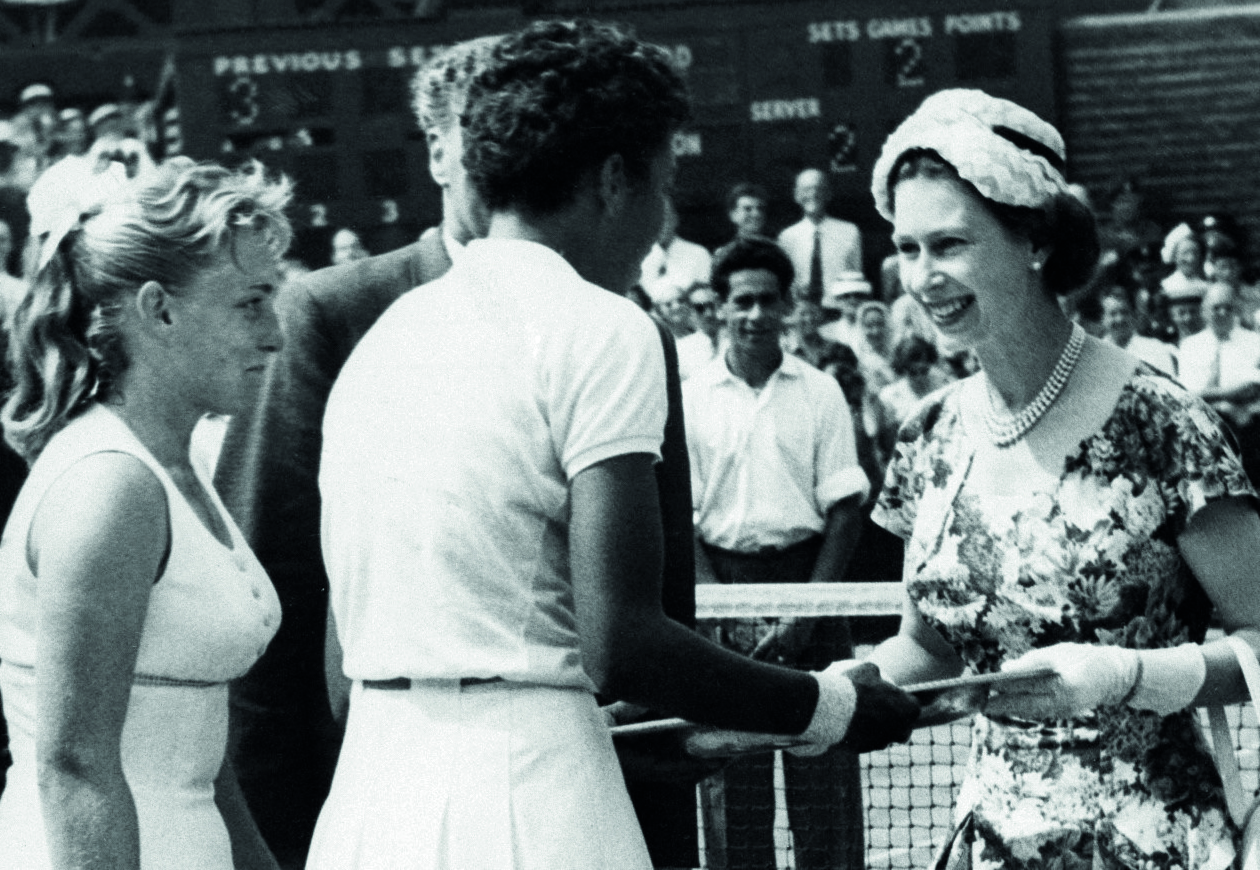

Helen Wills, a star of the 1920’s, replaced the more formal attire of her predecessors with pleated skirts and gamin tops that give her the élan of a flapper in an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. We picture her playing with that same sense of fun as someone sipping champagne at sunset on the French Riviera. But the style I find most irresistible among the well-known players is Althea Gibson’s. This extraordinary American black athlete broke the color barriers in both tennis and golf. She dressed with legerdemain—wearing the sort of clothing that implies that life is simple, you just wear what is sporty and nice looking, you don a bright yellow cardigan if you want a little bit of warmth; her clothing was like her smile, which is to say natural and easy.

There is a photograph of Gibson taken at the 1957 Wimbledon Women’s Single Championships, where Queen Elizabeth II presents her with the Venus Rosewater Dish. The Queen, smiling with what is truly joy from the heart, is dressed as royalty should be: a soft summer hat, three strands of pearls, pearl earrings, a flowered dress (the neckline showing just as much cleavage as her position would allow, and maybe a tiny bit more; she may have felt some of the same competitiveness about female matters for which her sister Margaret was far better known,) and white gloves to her elbows. Gibson is who she is as much as the Queen is: a tall, lean black woman dressed to win the game.

I cannot look at the photo without choking up. Talent at sports is one of the greatest human links in the world. Tennis is a game with unequaled elegance. You can have all the brightly colored Lycra and outrageous getups of today that you want, and if you prefer the colors of bowling shoes to the classic white of tennis, so be it. But when I see the genuineness that accompanies the style, and the sheer immersion in the rare pleasures of life, of those two true “ladies” in that glorious moment at Wimbledon, everything offered on the court—a term that, after all, means a place where royalty holds forth as well as a place where trials are judged—is sheer magic.

Story published in Courts N. 3, autumn 2018.